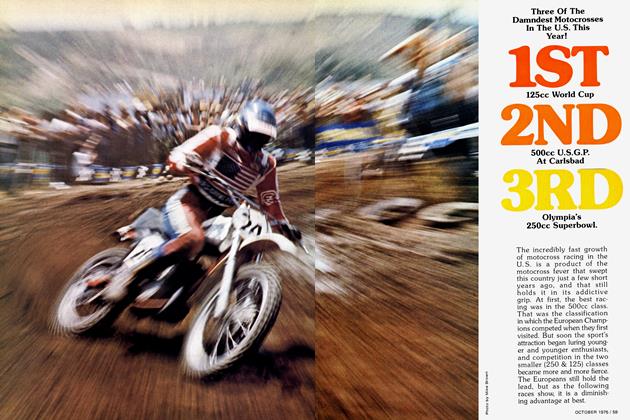

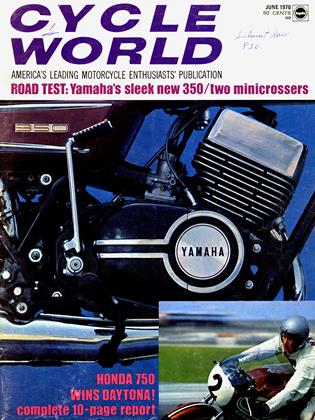

DAYTONA 1970

RACE OF THE CENTURY? NOT QUITE, BUT EXCITING AND VERY, VERY FAST.

IVAN J. WAGAR

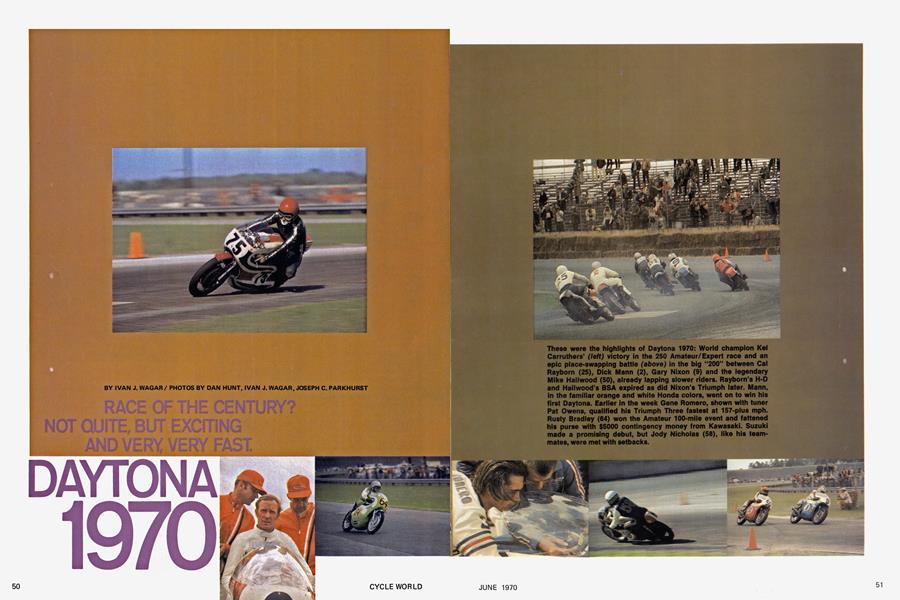

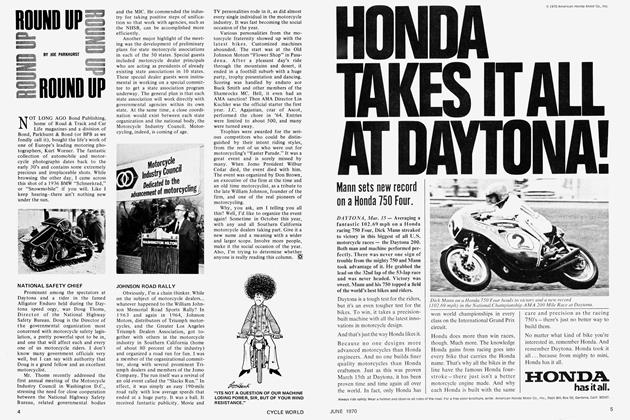

AN EMOTION-PACKED five-minute standing ovation, filling the banquet room of the Desert Inn, greeted Dick "Bugs" Mann as he reached for the Daytona 200 winner's trophy. Never in the 29-year history of the event has there been a more popular victor.

Mann has been trying to win the most prestigious race on the American calendar for 15 years. He has placed 2nd on two occasions. This year our National No. 2, so often the bridesmaid, made history by bringing the Honda Four its first AMA win, first time out.

And he didn’t even have a ride for Daytona a month before the race. As he says, “Industry has retired me.” Most of the manufacturers felt the 36-year-old veteran was so far over the hill he would not be the first rider to see the checkered flag in a major race. Bob Hansen, a long time racing sponsor and national service manager of American Honda, felt differently. Hansen insisted that “Bugs” would still be there at the finish, and never far off the pace. Hansen was dead right.

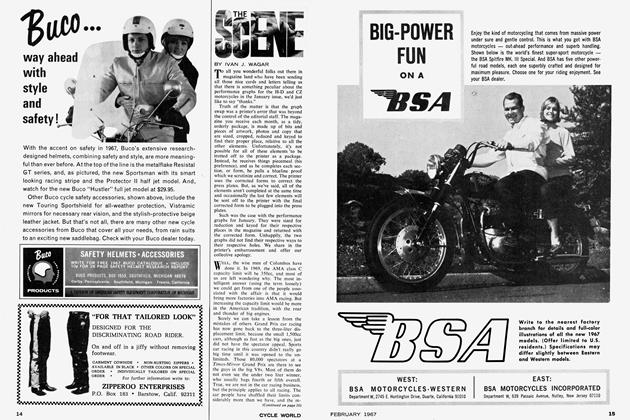

The grid, for what was expected to be the race of the century, featured nine-times world champion Mike Hailwood, former 50-cc world champion Ralph Bryans, and the current 250-cc world champion from Australia, Kel Carruthers, winner of the previous day’s 100-mile 250-cc race. No less than 17 foreign riders of international fame graced the grid.

Eager to prove that Americans are tops were our best hard surface specialists. When the star-studded 80-rider field lined up on the grid, 30,000 fans, almost double the previous high attendance, shuffled about as tension mounted to almost fever pitch at the “30-sec.-to-start” sign. The Canadian contingent was especially tense because the hero of the Maple Leaf country, Yvon du Hamel, failed to qualify his Trevor Deeley Yamaha, and was forced to start at the very back of the grid. An added handicap for the little French Canadian tiger was the fact that the starting lineup was divided into three groups to start at 5-sec. intervals. So one of the leading contenders would lose 10 sec. and have a tremendous traffic handicap over the first group riders.

In spite of the fact that ohv 750s were being allowed to run for the first time at Daytona (the previous regulations provided for two-stroke and ohv 500s and 750-cc sidevalves), the general run of qualifying times around the oval were not much faster than the previous year’s—except for one machine.

That was the 750-cc Triumph threecylinder of Gene Romero, sporting his new AMA National No. 3 this year. He averaged 157.342 mph around the oval, and his speed through the trap on the straight was just over 165 mph! The machine, like all the other factory Triumph and BSA Threes, was specially prepared for the race in Britain. The nicely refined engines, breathing through 1 3/16-in. Amal GP carbu retors, were estimated to develop about 25 percent more horsepower than the standard models and were wrapped in completely new duplex frames of trian gular loop design. Another deviation from standard was the five-speed Quaife-type gearbox, quite useful with the tall ratios you must pull at Daytona. To get the bikes hauled down, the factory adopted 250-mm four leading shoe front brakes, and a 9-in, hydraulic disc at the rear.

The other Threes ran only slightly faster than last year's top qualifier-the 151-mph Yamaha ridden by Yvon du Hamel. Hailwood's BSA qualified 2nd at 152.905, followed by Gary Nixon's Triumph, at 152.827. Percy Tait, 7th fastest at 150.577, was the only other rider of a Three to top 150 on the oval.

Dick Mann's Honda 750 Four, which posted a 152.67 1, was 4th fastest. This was just a bit faster than Kel Carruthers' trial. Kel turned 15 1.719 mph on what amounted to last year's 350 Yamaha racer, in design terms; the credit for tuning this rapid two-stroke goes to Californian Don Vesco, who established a Class C record at Bonneville last year on a similar machine. Sixth fastest was the factory 500-cc Suzuki Twin of Jody Nicholas at 151.133, greatly improved over last year's Daytona machines (April 1970).

The Honda Fours were quite similar to the machine that won the French Bol d'Or 24-Hour production race. Their The Honda Fours were quite similar to the machine that won the French Bol d’Or 24-Hour production race. Their frames appeared to be of standard con figuration, with braking suitably bol stered by twin discs up front and a massive finned drum at the rear. The crankcases on a few appeared to be sand-cast, while one had the standard die-cast finish. The engine breathed through four 36-mm vacuum assisted carburetors. Fastest of these, unoffi cially, was that of Ralph Bryans, turning a trap speed of more than 164 mph. Unfortunately, he had thrown it away during practice and it burned to a sooty grey heap before it could satisfy every one's curiosity in qualifying.

Mean while, Harley-Davidson, teething in its new ohv XR-750 V Twins, was hardly in the hunt, even after another round of frantic pre-race sessions on that long, deserted strip of Florida road. Fastest in qualifying: Bart Markel's, 15th at 147.540 mph. Cal Rayborn, road racing specialist of the Harley camp, managed a dismal 145.091 mph, slower than last year's time on the old KR.

In the Kawasaki camp, the H1R of Mark Williams emerged the fastest 500-cc Three at a respectable 148.490.

Disregarding Romero’s qualifying speed, the closeness in speed of the eight or ten fastest machines was remarkable. The new 750 rule has indeed increased the parity of machinery in regards to speed and thus the competitiveness of the whole scene. But oval racing is not road racing, and parities appear or disappear quite quickly, even on Daytona’s expansive infield circuit.

Dick Mann and his screaming Honda simply ran away from the rest of the pack as the flag fell. Mann continued to lead the first trip around the oval, but closing quickly were Gene “Burrito” Romero, fastest qualifier, and Gary Nixon on their fantastically quick Triumph Threes and second fastest qualifier Mike Hailwood on his very rapid BSA Three.

As the pack dove into the infield for the first time, Nixon, obviously fully recovered from his terrible accident last year, slipped by Burrito and Mann to become front runner and initiated his attack on the lap money gold. An unfortunate incident occurred at Turn 2 when an overly zealous first year Expert rammed into Art Baumann and, in turn, knocked the Suzuki ace into 1963 Daytona 200 winner Ralph White, sending them both to the hospital. Baumann severely dislocated his elbow, and White returned to California on crutches because of his badly sprained ankle. At the same turn our own “Agostini,” handsome Gene Romero, ran out of road and coasted around in the grass while a dozen riders went by. The lesson apparently stayed with him, because the young Triumph ace never put a wheel wrong for the next 197 miles. Fate befell Rod Gould as he turned onto the banking to find Andy Lascoutx and his Kawasaki Three going every which way less than three lengths ahead, and the game, red-headed Englishman joined White and Baumann.

Hailwood was downright scintillating at Turn 3, an almost flat-out left-hander that demands supreme courage and sorts the men from the boys. It was at this turn, in fact, that Mike slipped into 3rd spot behind Bugs as Cal Rayborn barged into 4th. Almost unnoticed was the fact that Kel Carruthers had placed his 350-cc Don Vesco-entered private Yamaha ahead of Rayborn.

By the end of five laps, counting the fast first lap around the oval, the race average was 108.244 mph. The actual lap average for the leaders on the 2.81-mile road circuit was about five mph above the old record, hovering around 106 mph. Hailwood flew through the infield but lost ground to Nixon on the banking. As these two great riders crossed the start-finish line at the end of Lap 5, they were less than a length apart, and less than 2 sec. separated the first four riders. The order was Nixon, Hailwood, Mann, Rayborn, closely followed by Carruthers on his diminutive Yamaha and the Suzuki 500 duo of Grant and Nicholas.

On the sixth tour Hailwood, as expected, honed his way by Nixon on the ballsy Turn 3 only to lose the advantage on the banking. No one can understand why the Triumphs, basically similar to the BSAs, are faster. Whatever the reason, the Triumph boys, including English factory test rider Percy Tait, really put it on all but Hailwood in the three-cylinder race.

Also on Lap 6, Jody Nicholas, while hard on the heels of teammate Ron Grant, pulled into the pits on one cylinder; his 500 Suzuki had devoured an ignition coil, thus ending the ride for the 7th place contender.

As if Jody’s retirement was some sort of signal to go after the lead, Grant really started to pour on the coals. On Lap 8 things really began to happen. First Mann passed Flailwood down the front straight, then Hailwood dove deep into the first turn and sneaked ahead of the Honda pilot. As both riders accelerated from the tricky decreasing-radius Turn 1, Bugs again shot ahead of Hailwood. Suddenly orange flames belched from “Mike the Bike’s” single-stack megaphone, and the world’s greatest road racer shot his left arm in the air, much to the amusement of the spectators not used to grand prix etiquette. The pack fled by. BSA had blown their wad. With dirt specialists Aldana and Rice on the team, it was a case of “Hailwood win or let’s go to lunch.” BSA went to lunch.

By Lap 10 it was obvious that Ron Grant did not care too much about who was around to give opposition, as he flung his Suzuki through the front-runners. Grant outbraked, outslid, and outdid everyone including Hailwood, proving the value of his winter racing in New Zealand. Every time Grant took the lead in the infield, however, he lost to Nixon on the oval. The 500 two-stroke was more than a match for the big 750 ohv on acceleration, but lacked the top speed to get the job done. The race average at the end of Lap 10 was 106.637 mph.

While the front-runners continued the record-breaking run, Yvon du Hamel cut some 107.5-mph laps on his 350 Yamaha to force his way into the first 15 places. Ireland’s Tommy Robb gamely held his Honda Four in 11th spot, and former three-time winner Roger Reiman managed to hold down 20th with his factory Harley-Davidson.

On Lap 13 it was elbow time for twice previous winner Rayborn and champion Carruthers. Neither rider gave an inch as they pitted 350 two-stroke against 750 ohv; nor did anyone in the stands appear willing to bet a nickel on the outcome.

The pressure was on Rayborn to uphold the Harley-Davidson honors. The Milwaukee factory has been running, and winning, the Daytona race for more years than most of us have been around; they simply are not used to losing. Cal, knowing that young Brelsford had pitted for the second time, and that Roger Reiman and Mert Lawwill were nowhere near, gassed it, but to no great advantage. Despite his very best efforts, Cal could not get rid of Carruthers, nor could he gain on Mann and the invincible Honda.

No less than five brands were featured in the first five places at the 20-lap mark, and all were within 30 seconds. Grant’s Suzuki led the field, as he lapped former champion Bart Markel, to pull away from Gary Nixon (Triumph), Mann (Honda), Carruthers (Yamaha) and Rayborn (Harley-Davidson).

Almost everyone blew their cool after the 20-lap signal. At a time when team tactics and programmed schedules should come into play, the big boys started to lose it. First to display overexuberance was old “Kool” Rayborn. He managed to zap both Carruthers and Mann, only to retire for good half a lap later—a broken valve. A similar fate was in store for all of the new 750-cc ohv Harley-Davidson XRs before the finish of the 200-mile race. For the first time in the history of the race the Milwaukee factory lost all of its runners.

While things looked gloomy in the Harley-Davidson camp, there were no big cheers from the Yamaha types either. Carruthers packed in on Lap 25 with a bad crankshaft, leaving du Hamel back in a lowly 9th spot, slightly behind New Zealand’s Ginger Malloy on a Kawasaki Three.

The pit stop scene was more than somewhat interesting. Nixon came in for a 29-sec. stop, at least 10 sec. more than normal. Towards the end of Gary’s fill-up, gasoline poured all over the rider, the machine and the roadway. The filler can had been designed to dump the full load of fuel when triggered—there was no way to shut off the flow once the release mechanism was operated. As a result, the tank accepted a little over three gallons, and another couple of gallons saturated everything in sight. Had Gary been involved in an accident when he went back out, he would have become a human torch.

Perhaps this is the time for the AMA to adopt a fueling procedure similar to that used at the Isle of Man, where the cans are mounted above the pits and a 12-ft. length of hose is equipped with a positive shut-off valve. Engines must be dead during the fueling operation. It would take slightly longer than the present system, but the time loss would be the same for everyone.

Kiwi Geoff Perry, son of a famous Norton factory rider of 20 years ago, filled up and took off smoothly. Up front, things were well under control. Grant had successfully blown everyone in the weeds. The gas sign went out for Grant as he flew by on Lap 26. Down to Turn 1. Misfire on the way to Turn 2. End of race. With a clear win in his pocket, the Suzuki star coasted and pushed back to the pits, only to find that he had, indeed, fried the engine as he ran out of fuel. If only the pit crew had calculated within a gallon, Grant could have made two stops and won easily.

When Gary disappeared on Lap 30 and Grant had done his thing, Dick Mann, always lurking only slightly off the pace, pulled his Honda into the lead position. For the next 23 laps the “Old Man” paced the Honda ahead of Romero, who had fought brilliantly to regain the time lost on the second lap. Youthful Don Castro, a first-year Expert, moved up to 3rd when Nixon went out and did an amazing job of keeping the big Triumph under control. It was Castro’s first time to use clip-on bars.

With 10 laps remaining, du Hamel began a scrap with Castro for 3rd place. In the infield du Hamel would force the little Yamaha ahead, only to lose to the Triumph on the banking. Both riders were lapping at 2 min., 13 sec., but horsepower won out, and the plucky du Hamel had to pit his overstressed Yamaha for more than a minute on Lap 46. Frank Camillieri retired his Boston Yamaha from 6th place with a half dozen laps remaining.

Romero whittled the gap down to 10 sec. five laps from the end, but Hansen gave Bugs the message and the Honda pulled back 3 sec. on the next two tours. The Triumph pits hung out the “Go Fast” boards to Romero as the Honda’s exhaust note began to sour, but Mann, going only as fast as necessary to win, took the flag with 10 sec. in hand.

Mann lapped all but 2nd and 3rd places at least once. Of the more than 80 starters, only 24 remained at the finish. The short development time on the new engines had led to a very high failure rate. The only Harley-Davidson to finish was the old sidevalve KR ridden by Walt Fulton. All of the new XR engines broke valves, despite hours of testing prior to the race. Of the BSAs and Triumphs that were sidelined, all suffered piston failure, which did not occur during endless testing in England. Suzuki’s only finisher was teen-aged Geoff Perry of New Zealand, who also rode a 1969 machine. The young Kiwi rode a very heady, consistent race to finish 4th.

The little 350 Yamahas were identical to those used last year. In fact, with no official Yamaha Team, most of the machines were 1969 models. With riders like du Hamel and Carruthers turning laps around 104 mph, the engines were wrung too tightly to survive the distance.

All three first finishers used rear tires on both ends. Mann turned down the massive Dunlops that came on the ma chine; the rear was a full 5 in. at the widest point, for a pair of very wide profile 3.50-18 Goodyears. The rubber compound was slightly softer in the front, for maximum traction, than on the more highly stressed rear tire. Tri umph riders Romero and Castro ran a similar combination.

250-CC AMATEUR/EXPERT

Yamaha did, however, completely walk away with the honors in the combined 250-cc race by taking 18 of the first 20 places. Only Ron Grant and Jody Nicholas on Suzukis prevented Yamaha from absolute domination.

The two 5-lap qualifying heats for the 100-mile 250 race whetted appetites and gave a preview of very exciting things to come. Gary Nixon looked all set to run away with the first heat until Amateur Steve McLaughlin dove inside the former champ on the first turn. A real donnybrook developed as these two pulled away from the field. Third place was in doubt all the way as Chuck Palmgren did a masterful job of pitting his Yamaha against Grant’s and Nicholas’ Suzukis. Nixon took the flag at a speed of 91.292 mph, well down on his full race average of 94.094 set in 1967.

The second heat was electrifying. World Champion Carruthers and England’s Rod Gould screamed their private Yamahas to a blistering 100.490 mph average for the five laps and finished 7 sec. ahead of Englishman Tony Smith (Suzuki). Carruthers felt his Wixom fairing, an innovation adopted by sponsor Don Vesco, offered an advantage in high speed handling over the standard Yamaha component. Smith did not have everything his own way; Ralph White and Frank Camillieri fought every inch of the race. Cal Rayborn, under the new AMA rules for lightweight racing, wheeled out a 350 Sprint which was expected to give the 250s a bad time. At the end, however, Cal was a very low 10th place, proving that the larger displacement allowance for four-strokes might not be unfair after all.

As the starter’s flag fell for the big one, the angry rasp of what seemed like thousands of two-strokes filled the Daytona bowl. Heat race record-breakers Carruthers and Gould were at the back of the first dozen. Palmgren again displayed brilliance by leading the field into the first turn. But, as everyone braked hard for the difficult decreasing radius bend, Gould and Carruthers stayed on the tank and shot to the front. It was Nixon who outbraked the leaders on the next tour, only to have the engine go belly-up as he tried to accelerate from the turn. By Lap 3 it was obvious that, barring an accident or mechanical failure, the race would be between Gould and Carruthers. Even du Hamel could not match the 103-mph pace being set by the flying duo.

Cal Rayborn pitted at the end of Lap 5—to find an empty pit. Apparently the mechanics were more concerned with finding more horsepower from the big machines for the Sunday race.

Ron Pierce screamed from the pack to challenge du Hamel for 3rd place, and for several laps these two fine riders remained inches apart, even as they lapped slower traffic.

By the end of five laps the leaders had lapped several tail-enders, clear proof that something must be done about a grading system. Dusty Coppage, the TT specialist, had lapped six riders by the end of his ninth lap.

Carruthers maintained a fantastic 100.412-mph average for the first 10 laps. On the next lap Ralph White came from nowhere to join the Pierce-du Hamel scrap for 3rd spot, but 22 sec. behind Carruthers. Carruthers also had a comfortable 6 sec. on Gould.

San Diego’s Don Emde, son of the 1948 200 winner, was the only Amateur in the first 10 places. He and Palmgren were having their private scrap behind the White-du Hamel-Pierce battle.

Looking every inch a world champion, Carruthers continued his devastating pace. Cool, comfortable and relaxed, he was never off line a foot as he

passed the 15-lap mark, still averaging over the magic 100-mph figure.

Chuck Palmgren was forced to let Emde go on the 18th lap. His Yamaha cried enough. Eor a dirt rider he had put in a beautiful ride.

Farther back, in 8th and 9th places, Ron Grant and Jody Nicholas took turns slipstreaming, their Suzukis badly outpaced by the Yamahas. Both Grant and Nicholas almost crashed as they lapped a slower rider going into the first bend on Lap 24. All three machines touched for a horrible fraction of a second at more than 100 mph, but everyone managed to get clear.

Carruthers took the flag with an average speed of 98.857, almost 5 mph faster than Gary Nixon’s 1967 record. Gould was 11 sec. down on the champion, but a safe distance behind the du Hamel-Pierce battle. Kel’s only anxious moment during the whole ride came when he had to take to the grass to avoid a fallen rider. The popular Aussie enjoyed his first visit to the U.S., and while he has no plans to return for any future AMA races this year, he is most anxious to ride here again.

Despite rumors to the contrary, Carruthers will again ride for Benelli in all grands prix this year. Plans for a 500-cc Vee Eight are canceled because of the FIM’s impending four-cylinder limit, so the 35 0 and 500 rides will be updated four-cyhnder models. The FIM’s current restriction of two cylinders and six transmission speeds has made last year’s championship Four obsolete. Kel hopes to use his 250 Yamaha while the Pre s ar o-based Benelli factory continues work on an all new 250-cc two-stroke Twin. It should be a very interesting grand prix season.

(Continued on page 60)

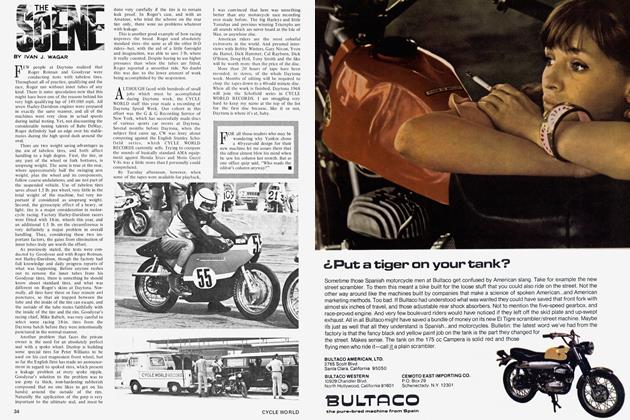

100-MILE AMATEUR

Skeptics laughed when Kawasaki posted its now famous half-million dollar contingency award bonus. But it was a young Texas college student who laughed the loudest after the Amateur 100-mile race. Long-haired, mild-mannered Rusty Bradley picked up $5000 from the equally happy Kawasaki gang after tooling his modified HI three-cylinder racer to an overwhelming victory. Rusty really shocked the troops when he qualified a tremendous 15 mph over the old Amateur qualifying record. Prerace favorites Gary Fisher, Don Emde and Ray Hempstead turned white when Bradley’s speed was announced.

Rusty’s 149.130 mph, accomplished with a machine giving away 250 cc to the class limit, was exactly the same as the 9th fastest Expert qualifier for the 200, and approximately 1 mph up on Fisher, the next fastest Amateur.

Fisher balked slightly on the start, permitting Bradley to move away with out challenge from the grid. Obviously Fisher was hampered by the four-speed transmission in his privately tuned Tri umph Three. The official BSA and Triumph entries in the 200-Miler all had five-speed gearsets, a must when pulling the very high Daytona gearing.

Recovering from the starting handi cap very quickly, Fisher gobbled up riders like mad on the first trip around the oval and finally dived into 2nd place as they went into the infield for the first time. But there was no catching Brad ley, who, by the end of the second tour, had put 4 sec. between himself and 2nd place.

The Kawasaki was really flying, and Bradley took every advantage of his tremendous skill in the twisty infield. Cutting laps at 2 mm., 14 sec., Bradley had pulled out 17 sec. by Lap 10. Second place Fisher had 4 sec. over Sears Point Amateur winner Dunn and his Suzuki.

The only question remaining was whether Rusty would keep the Kawasa ki on its wheels. The lad is known for throwing the bike down the road fre quently and with great dexterity. Prob ably the biggest contributor to con tinued progress was the fact that he stepped off at Turn 2 on Tuesday's practice session, destroying the machine in the process. Whatever the lessons or coaching, Rusty rode like a pro every inch of the way.

At half distance Don Emde had worked his way into 4th, behind last year's 2nd place Ray Hempstead. Rusty's usual riding partner, Virgil Davenport, also a Texan was almost two laps behind the leader. And Rusty had also lapped 10th place man Jerry How erton, who was riding Don Vesco's standard BSA Three engine in a Metisse chassis.

By the 20th tour Bradley had drop ped his speed to 2 mill., 15 sec., and still had 22 sec. over Fisher. Kawasaki rider Blochinger really botched his pit stop when he used too much front brake and crashed in front of his pit crew. Young Rudy Galindo began to make his bid for the top and sliced by Emde in a very positive manner in the battle for 4th, only to be joined by Duane McDaniels, to further complicate matters.

When Rusty received the yellow flag it was like a transformation. As if the five grand and the other rewards of winning were within his grasp, he slowed to a neat, cagey 2 min., 18 sec. last lap. Where he had been using almost every inch of the road on the dangerously fast Turn 3 in the early laps, he stayed almost in the middle of the road. At no time on the last tour did he get anywhere near a slower rider in a turn. Superb cool\

Rusty became the first Amateur to win Daytona at over 100 mph, and certainly must be the leading contender for all road race nationals this year. Kawasaki must have a crystal ball somewhere. They not only supplied a gourmet lunch and bar facilities for some of their friends (fortunately this reporter was included), but also the very pleasant company of beautiful Ann-Margret. Congratulations, Kawasaki.

78-MILE NOVICE 250

High school student Jerry Christopher piloted his Yamaha to a record breaking 94.395-mph average to win the 78-mile Novice 250 race. The West Covina, Calif, youth never put a wheel wrong as he completely dominated the event.

Early leader Conrad Urbanowski looked all set to do great things until Christopher came by on the third lap. Christopher was, in fact, lapping back markers by Lap 3, another indication that something must be done about rider grading.

So complete was the Yamaha domination that no other brand featured in the first 10 places. In fact, except for a Suzuki and a Ducati, Yamaha controlled the first 20 places.

There was an anxious moment on the fourth lap as a panic stricken ambulance driver screamed up the grid in the wrong direction at about 60 mph. Fortunately no one pitted and the paying spectators were spared the sight of a rider running head-on into a car.

The race opened up on Lap 18 when Urbanowski, holding a solid 2nd place, crashed coming out of the infield, putting Christopher 46 sec. ahead of 2nd place. Ron Dottley inherited 2nd while Doug Teague and Jeff March had a good scrap for 3rd, which lasted right to the flag.

Christopher plans to finish his studies and continue racing, but he places school ahead of a racing career. With the kind of dedication he displayed at Daytona, he will very likely succeed at both.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

JUNE 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Legislation Forum

Legislation ForumIllinois Success Story

JUNE 1970 By Lee Strobel -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

JUNE 1970 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

JUNE 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Features

FeaturesOverland Adventure

JUNE 1970 By Dean Haagenson -

Competition

CompetitionThe Mint 400, '70 Style

JUNE 1970 By Bryon Farnsworth