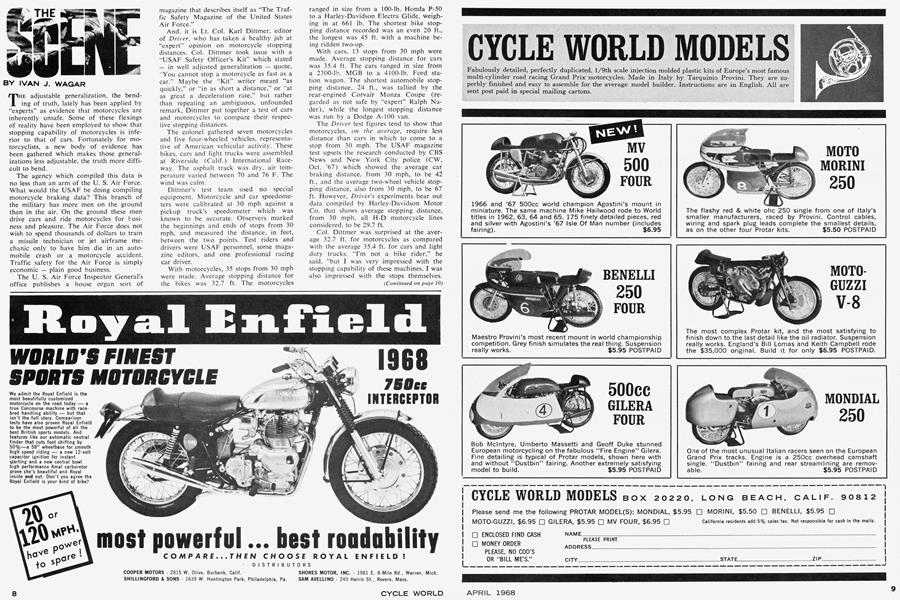

THE SCENE

IVAN J. WAGAR

THE adjustable generalization, the bending of truth, lately has been applied by "experts" as evidence that motorcycles are inherently unsafe. Some of these flexings of reality have been employed to show that stopping capability of motorcycles is inferior to that of cars. Fortunately for motorcyclists, a new body of evidence has been gathered which makes those generalizations less adjustable, the truth more difficult to bend.

The agency which compiled this data is no less than an arm of the U. S. Air Force. What would the USAF be doing compiling motorcycle braking data? This branch of the military has more men on the ground than in the air. On the ground these men drive cars and ride motorcycles for business and pleasure. The Air Force does not wish to spend thousands of dollars to train a missile technician or jet airframe mechanic only to have him die in an automobile crash or a motorcycle accident. Traffic safety for the Air Force is simply economic — plain good business.

The U. S. Air Force Inspector General's office publishes a house organ sort of magazine that describes itself as "The Traffic Safety Magazine of the United States Air Force."

And, it is Lt. Col. Karl Dittmer, editor of Driver, who has taken a healthy jab at "expert" opinion on motorcycle stopping distances. Col. Dittmer took issue with a "USAF Safety Officer's Kit" which stated — in well adjusted generalization — quote, "You cannot stop a motorcycle as fast as a car." Maybe the "Kit" writer meant "as quickly," or "in as short a distance," or "at as great a deceleration rate," but rather than repeating an ambiguous, unfounded remark, Dittmer put together a test of cars and motorcycles to compare their respective stopping distances.

The colonel gathered seven motorcycles and five four-wheeled vehicles, representative of American vehicular activity. These bikes, cars and light trucks were assembled at Riverside (Calif.) International Raceway. The asphalt track was dry, air temperature varied between 70 and 76 F. The wind was calm.

Dittmer's test team used no special equipment. Motorcycle and car speedometers were calibrated at 30 mph against a pickup truck's speedometer which was known to be accurate. Observers marked the beginnings and ends of stops from 30 mph, and measured the distance, in feet, between the two points. Test riders and drivers were USAF personnel, some magazine editors, and one professional racing car driver.

With motorcycles, 35 stops from 30 mph were made. Average stopping distance for the bikes was 32.7 ft. The motorcycles ranged in size from a 100-lb. Honda P-50 to a Harley-Davidson Electra Glide, weighing in at 661 lb. The shortest bike stopping distance recorded was an even 20 ft., the longest was 45 ft. with a machine being ridden two-up.

With cars, 13 stops from 30 mph were made. Average stopping distance for cars was 35.4 ft. The cars ranged in size from a 2300-lb. MGB to a 4100-lb. Ford station wagon. The shortest automobile stopping distance, 24 ft., was tallied by the rear-engined Corvair Monza Coupe (regarded as not safe by "expert" Ralph Nader), while the longest stopping distance was run by a Dodge A-100 van.

The Driver test figures tend to show that motorcycles, on the average, require less distance than cars in which to come to a stop from 30 mph. The USAF magazine test upsets the research conducted by CBS News and New York City police (CW, Oct. '67) which showed the average car braking distance, from 30 mph, to be 42 ft., and the average two-wheel vehicle stopping distance, also from 30 mph, to be 67 ft. However, Driver's experiments bear out data compiled by Harley-Davidson Motor Co. that shows average stopping distance, from 30 mph, all H-D motorcycle lines considered, to be 29.7 ft.

Col. Dittmer was surprised at the average 32.7 ft. for motorcycles as compared with the average 35.4 ft. for cars and light duty trucks. "I'm not a bike rider," he said, "but I was very impressed with the stopping capability of these machines. I was also impressed with the stops themselves. Without exception, every stop went straight down the lane. This includes the two stops that ended in step-offs . . .

(Continued on page 10)

"I was less impressed with the autos . . . we made the auto runs well before the track started to get slick from all the rubber laid down by the bikes, yet almost every driver had a tendency to lock up the wheels."

In the Driver test report, this paragraph bears out what knowledgeable motorcyclists have known for a long while: "It takes a whole lot more skill to stop a car quickly, accurately and precisely in a straight line than it takes to make it go fast. A motorcycle, like a car, requires even more careful handling, especially during those last few feet when, due to its very low speed, it loses a certain amount of stability. A car isn't likely to fall over on its rider, but a motorcycle has a whole lot less weight and mass to stop with its brakes. A machine in good condition, driven by an experienced rider, has to be one of the best combinations on the road."

And, Dittmer said, . . these tests serve only as a guide. All of us who participated are fairly confident that the test results are reasonably accurate — certainly accurate enough to give an honest measure of how well an expertly-manned two-wheeler compares to the average — and better than average — automobile when both are stopped on dry pavement from an approximate speed of 30 mph."

The next time anyone within CYCLE WORLD hearing says, "You can't stop a motorcycle as fast as a car," this generalizer will be quickly adjusted by a fast trip to the files where the Dittmer diary is kept.

THE Texas Department of Public Safety has done itself proud in preparation of a Motorcycle Supplement to the Texas Drivers Handbook, and a Special Motorcycle Road Rules Test.

With such statements as, "A motorcycle is not in itself dangerous," the Lone Star State's public safety officials make it clear they are not of the all-too-common head-in-sand breed.

The writers of the supplement booklet, unfortunately unidentified, state that a motorcycle offers the advantages of unlimited visibility and stability, and disadvantages in that it lacks protection for the rider and can become unstable quickly on ice or gravel. To knowledgeable riders, it soon becomes apparent these safety types have ridden a motorcycle or two.

The supplement offers a check list for the novice cyclist, including the necessities of good brakes, adequate lights, well adjusted spokes, and properly inflated tires. Rudimentary, sure, but this is advice well given to the beginning motorcyclist.

The Texans advocate adequate clothing, "preferably leather," and the safety helmet. To wit: "The first piece of personal protective equipment a motorcyclist should purchase is a helmet . . . This is required by common sense."

The supplement continues with cogent passages on handling of motorcycles on slippery surfaces, in wind, and while riding two-up. CW staffers, with an accumulated 60 to 70 years of riding experience, couldn't argue with Texas words of advice.

The accompanying rules test, a multiple choice examination of 40 questions, is designed to determine just how thoroughly the would-be motorcyclist has assimilated the advice and information, and rules of the road discussed in the 14-page booklet.

It is obvious that no booklet or written exam ever created a competent motorcyclist. However, recognition by the Texas Department of Public Safety that motorcycles are a fact of life, and that preparation means safe riding, can, CYCLE WORLD is sure, start fledgling motorcyclists in the proper direction.

The Lone Star State's excellent work could well serve as a model for some of the other 49.

AT press time, we learned that Phil Read, Yamaha, scored a shock win over Giacomo Agostini. MV, in the 350-cc class of the opening road race meeting of the European season, at Alicante, Spain.

Read's machine was an over-sized version of the 250-cc V-4s. It was making its first European appearance. Read, who will race 250and 350-cc Yamahas at Daytona, set a new class lap record at 89.93 mph. Agostini used one of the familiar MV-3s.

ONE of the highlights of my trip to Spain was a look at the little Ossa grand prix rotary valve 250 racer. I'm sorry there are no photos, but photographing the machine was the only thing I was not permitted to do. There was no limit on looking time; there was even no restriction on examination of the disassembled engine.

(Continued on page 12)

The engine was stripped for final preparation in advance of the Alicante race, first international road race of the 1968 season. Had the Alicante races not been so near, a ride would most certainly have been arranged for me.

Dick Mann rode the 250 during the week before I arrived in Spain, and reckoned he easily could win the Daytona 200miler if rules permitted such a weapon. In typical Mann fashion, he said he felt there would be little question about still being No. 1 — if.

The engine, by most standards, may seem rather ordinary. However, the engine castings are, without exception, the most beautiful I have seen on any motorcycle — racing or otherwise. All major castings are elektron (magnesium), and internally finished to the nth degree throughout. A sixspeed transmission is not considered a luxury, but a necessity for a Single that must do battle with the multi-cylinder giants. The most unusual thing about the Ossa was its frame. A backbone type monocoque chassis, weighing 7 lb., resulted in a total dry weight of less than 220 lb. The rear swinging arm has been constructed from American 4130 mild steel tubing, which delivers the best strength/weight ratio for smaller components.

Credit for the existence of the little racer must go to Ossa Development Engineer, Eduardo Giro. Son of the owner of Ossa, Eduardo, at age 26, most certainly will eventually be rated among the foremost engineers in the world of motorcycling. The rotary valve 250, Eduardo's first engineering project, develops over 44 hp with reliability.

The rear suspension of the grand prix Ossa is almost as unusual as the new chassis. Working in close company with Telesco, Ossa has tried several variations of the basic "springless" system for more than a year. Now there are valves to adjust the transfer rate of air and oil, making possible suspension changes during the race.

AT press time we learned the shattering news that Honda almost certainly has decided to pull out of racing in 1968. Team riders Mike Hailwood and Ralph Bryans returned to England from Japan, where they discovered there were no new 1968 machines for them to test. Neither would comment on the situation. All Hailwood would reveal was that Honda definitely will not contest the Isle of Man TT. Their silence appears to confirm that Honda has decided on a 100 percent withdrawal.