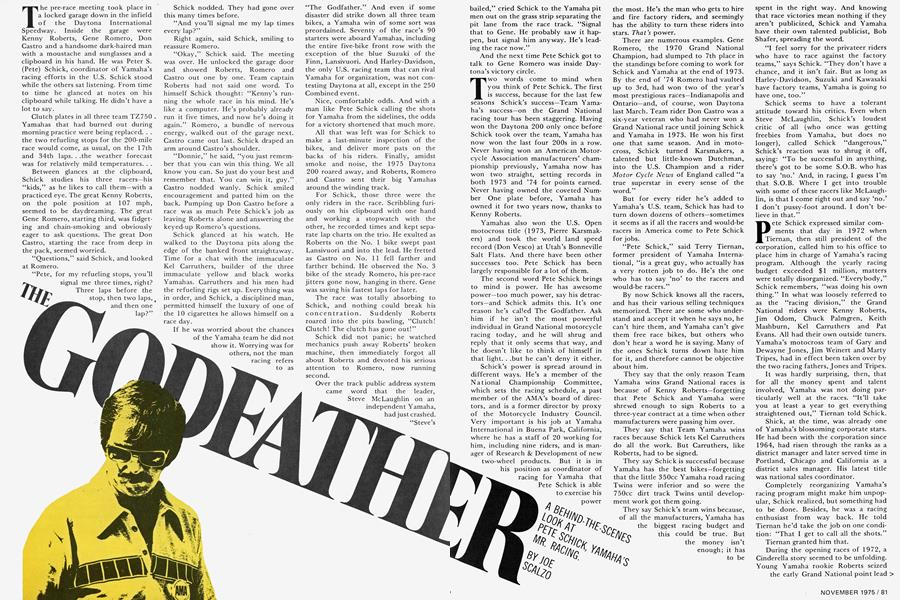

THE GODFATHER

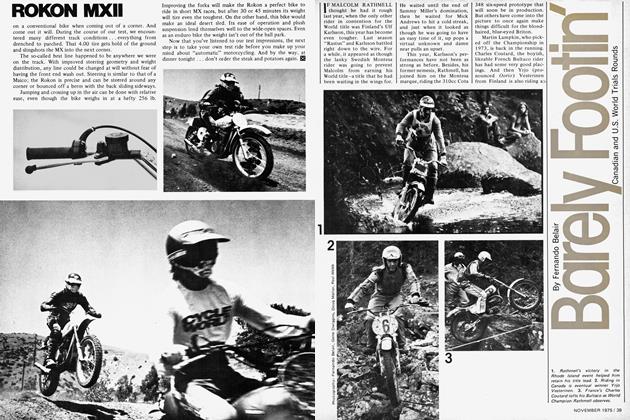

The pre-race meeting took place in a locked garage down in the infield of the Daytona International Speedway. Inside the garage were Kenny Roberts, Gene Romero, Don Castro and a handsome dark-haired man with a moustache and sunglasses and a clipboard in his hand. He was Peter S. (Pete) Schick, coordinator of Yamaha’s racing efforts in the U.S. Schick stood while the others sat listening. From time to time he glanced at notes on his clipboard while talking. He didn’t have a lot to say.

Clutch plates in all three team TZ750 . Yamahas that had burned out during morning practice were being replaced. . . the two refueling stops for the 200-mile race would come, as usual, on the 17th and 34th laps. . .the weather forecast was for relatively mild temperatures. . .

. . Between glances at the clipboard, Schick studies his three racers—his “kids,” as he likes to call them—with a practiced eye. The great Kenny Roberts, on the pole position at 107 mph, seemed to be daydreaming. The great Gene Romero, starting third, was fidgeting and chain-smoking and obviously eager to ask questions. The great Don Castro, starting the race from deep in the pack, seemed worried.

“Questions,” said Schick, and looked at Romero.

“Pete, for my refueling stops, you’ll signal me three times, right? Three laps before the stop, then two laps, and then one lap?” Schick nodded. They had gone over this many times before.

“And you’ll signal me my lap times every lap?”

Right again, said Schick, smiling to reassure Romero.

“Okay,” Schick said. The meeting was over. He unlocked the garage door and showed Roberts, Romero and Castro out one by one. Team captain Roberts had not said one word. To himself Schick thought: “Kenny’s running the whole race in his mind. He’s like a computer. He’s probably already run it five times, and now he’s doing it again.” Romero, a bundle of nervous energy, walked out of the garage next. Castro came out last. Schick draped an arm around Castro’s shoulder.

“Donnie,” he said, “you just remember that you can win this thing. We all know you can. So just do your best and remember that. You can win it, guy.” Castro nodded wanly. Schick smiled encouragement and patted him on the back. Pumping up Don Castro before a race was as much Pete Schick’s job as leaving Roberts alone and answering the keyed-up Romero’s questions.

Schick glanced at his watch. He walked to the Daytona pits along the edge of the banked front straightaway. Time for a chat with the immaculate Kel Carruthers, builder of the three immaculate yellow and black works Yamahas. Carruthers and his men had the refueling rigs set up. Everything was in order, and Schick, a disciplined man, permitted himself the luxury of one of the 10 cigarettes he allows himself on a race day.

If he was worried about the chances of the Yamaha team he did not show it. Worrying was for others, not the man racing refers to as “The Godfather.” And even if some disaster did strike down all three team bikes, a Yamaha win of some sort was preordained. Seventy of the race’s 90 starters were aboard Yamahas, including the entire five-bike front row with the exception of the blue Suzuki of the Finn, Lansivuori. And Harley-Davidson, the only U.S. racing team that can rival Yamaha for organization, was not contesting Daytona at all, except in the 250 Combined event.

Nice, comfortable odds. And with a man like Pete Schick calling the shots for Yamaha from the sidelines, the odds for a victory shortened that much more.

All that was left was for Schick to make a last-minute inspection of the bikes, and deliver more pats on the backs of his riders. Finally, amidst smoke and noise, the 1975 Daytona 200 roared away, and Roberts, Romero and Castro sent their big Yamahas around the winding track.

For Schick, those three were the only riders in the race. Scribbling furiously on his clipboard with one hand and working a stopwatch with the other, he recorded times and kept separate lap charts on the trio. He exulted as Roberts on the No. 1 bike swept past Lansivuori and into the lead. He fretted as Castro on No. 11 fell farther and farther behind. He observed the No. 3 bike of the steady Romero, his pre-race jitters gone now, hanging in there. Gene was saving his fastest laps for later.

The race was totally absorbing to Schick, and nothing could break his concentration. Suddenly Roberts roared into the pits bawling, “Clutch! Clutch! The clutch has gone out!”

Schick did not panic; he watched mechanics push away Roberts’ broken machine, then immediately forgot all about Roberts and devoted his serious attention to Romero, now running second.

Over the track public address system came word that the leader, Steve McLaughlin on an independent Yamaha, had just crashed.

“Steve’s bailed,” cried Schick to the Yamaha pit men out on the grass strip separating the pit lane from the race track. “Signal that to Gene. He probably saw it happen, but signal him anyway. He’s leading the race now.”

A BEHIND-THE-SCENES LOOK AT PETE SCHICK, YAMAHA'S MR. RACING.

JOE SCALZO

And the next time Pete Schick got to talk to Gene Romero was inside Daytona’s victory circle.

Two words come to mind when you think of Pete Schick. The first is success, because for the last few seasons Schick’s success—Team Yamaha’s success—on the Grand National racing tour has been staggering. Having won the Daytona 200 only once before Schick took over the team, Yamaha has now won the last four 200s in a row. Never having won an American Motorcycle Association manufacturers’ championship previously, Yamaha now has won two straight, setting records in both 1973 and ’74 for points earned. Never having owned the coveted Number One plate before, Yamaha has owned it for two years now, thanks to Kenny Roberts.

Yamahas also won the U.S. Open motocross title (1973, Pierre Karsmakers) and took the world land speed record (Don Vesco) at Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats. And there have been other successes too. Pete Schick has been largely responsible for a lot of them. The second word Pete Schick brings to mind is power. He has awesome power—too much power, say his detractors—and Schick admits this. It’s one reason he’s called The Godfather. Ask him if he isn’t the most powerful individual in Grand National motorcycle racing today, and he will shrug and reply that it only seems that way, and he doesn’t like to think of himself in that light. . .but he can’t deny it either.

Schick’s power is spread around in different ways. He’s a member of the National Championship Committee, which sets the racing schedule, a past member of the AMA’s board of directors, and is a former director by proxy of the Motorcycle Industry Council. Very important is his job at Yamaha International in Buena Park, California, where he has a staff of 20 working for him, including nine riders, and is manager of Research & Development of new two-wheel products. But it is in his position as coordinator of racing for Yamaha that Pete Schick is able to exercise his power

the most. He’s the man who gets to hire and fire factory riders, and seemingly has the ability to turn these riders into stars. That’s power.

There are numerous examples. Gene Romero, the 19 70 Grand National Champion, had slumped to 7th place in the standings before coming to work for Schick and Yamaha at the end of 1973. By the end of ’74 Romero had vaulted up to 3rd, had won two of the year’s most prestigious races—Indianapolis and Ontario—and, of course, won Daytona last March. Team rider Don Castro was a six-year veteran who had never won a Grand National race until joining Schick and Yamaha in 1973. He won his first one that same season. And in motocross, Schick turned Karsmakers, a talented but little-known Dutchman, into the U.S. Champion and a rider Motor Cycle News of England called “a true superstar in every sense of the word.”

But for every rider he’s added to Yamaha’s U.S. team, Schick has had to turn down dozens of others—sometimes it seems as if all the racers and would-be racers in America come to Pete Schick for jobs.

“Pete Schick,” said Terry Tiernan, former president of Yamaha International, “is a great guy, who actually has a very rotten job to do. He’s the one who has to say ‘no’ to the racers and would-be racers.”

By now Schick knows all the racers, and has their various selling techniques memorized. There are some who understand and accept it when he says no, he can’t hire them, and Yamaha can’t give them free race bikes, but others who don’t hear a word he is saying. Many of the ones Schick turns down hate him for it, and therefore cannot be objective about him.

They say that the only reason Team Yamaha wins Grand National races is because of Kenny Roberts—forgetting that Pete Schick and Yamaha were shrewd enough to sign Roberts to a three-year contract at a time when other manufacturers were passing him over.

They say that Team Yamaha wins races because Schick lets Kel Carruthers do all the work. But Carruthers, like Roberts, had to be signed.

They say Schick is successful because Yamaha has the best bikes—forgetting that the little 350cc Yamaha road racing Twins were inferior and so were the 750cc dirt track Twins until development work got them going.

They say Schick's team wins because, of all the manufacturers, Yamaha has the biggest racing budget and this could be true. But the money isn't enough; it has to be

spent in the right way. And knowing that race victories mean nothing if they aren’t publicized, Schick and Yamaha have their own talented publicist, Bob Shafer, spreading the word.

“I feel sorry for the privateer riders who have to race against the factory teams,” says Schick. “They don’t have a chance, and it isn’t fair. But as long as Harley-Davidson, Suzuki and Kawasaki have factory teams, Yamaha is going to have one, too.”

Schick seems to have a tolerant attitude toward his critics. Even when Steve McLaughlin, Schick’s loudest critic of all (who once was getting freebies from Yamaha, but does no longer), called Schick “dangerous,” Schick’s reaction was to shrug it off, saying: “To be successful in anything, there’s got to be some S.O.B. who has to say ‘no.’ And, in racing, I guess I’m that S.O.B. Where I get into trouble with some of these racers like McLaughlin, is that I come right out and say ‘no.’ I don’t pussy-foot around. I don’t believe in that.”

Ï^ete Schick expressed similar comW ments that day in 1972 when Tiernan, then still president of the corporation, called him to his office to place him in charge of Yamaha’s racing program. Although the yearly racing budget exceeded $1 million, matters were totally disorganized. “Everybody,” Schick remembers, “was doing his own thing.” In what was loosely referred to as the “racing division,” the Grand National riders were Kenny Roberts, Jim Odom, Chuck Palmgren, Keith Mashburn, Kel Carruthers and Pat Evans. All had their own outside tuners. Yamaha’s motocross team of Gary and Dewayne Jones, Jim Weinert and Marty Tripes, had in effect been taken over by the two racing fathers, Jones and Tripes.

It was hardly surprising, then, that for all the money spent and talent involved, Yamaha was not doing particularly well at the races. “It’ll take you at least a year to get everything straightened out,” Tiernan told Schick.

Shick, at the time, was already one of Yamaha’s blossoming corporate stars. He had been with the corporation since 1964, had risen through the ranks as a district manager and later served time in Portland, Chicago and California as a district sales manager. His latest title was national sales coordinator.

Completely reorganizing Yamaha’s racing program might make him unpopular, Schick realized, but something had to be done. Besides, he was a racing enthusiast from way back. He told Tiernan he’d take the job on one condition: “That I get to call all the shots.” Tiernan granted him that.

During the opening races of 1972, a Cinderella story seemed to be unfolding. Young Yamaha rookie Roberts seized the early Grand National point lead and held it through June before nerves and mechanical blowups took their toll. By the end of the year, Roberts and Yamaha had slumped to 4th in the standings behind Mark Breisford (Harley-Davidson), Gary Scott and Gene Romero (Triumph). But Schick had expected this to happen, so wasn’t unduly upset.

“Our bikes just weren’t fast enough,” he explained. “Kenny surprised Harley by starting so fast, but by summer Harley had its act together and just kicked the hell out of us.” But Schick had stayed within his budget for the entire season, and this was a victory of sorts: it was the first time in the history of Yamaha’s racing team that the budget had not been exceeded.

For 1973, Schick rolled up his sleeves and went to work. Dropped from the Grand National team were Mashburn, Odom and Palmgren, but Schick signed Roberts to a three-year contract, got Don Castro away from Triumph and signed him for two years, and put Gary Fisher under a one-year road racing contract. Tired of squabbling with what he called “the father and son teams,” he disbanded the Yamaha motocross program and invited an experienced Dutchman, Pierre Karsmakers, over for a season. And, to coordinate the work, he placed the veteran tuner Shell Thuett under contract and in charge of Grand National dirt track racing, and hired Kel Carruthers to be boss of the road racing tuners.

It was Schick’s idea that Roberts, Castro and Fisher be paid monthly salaries no matter what, be paid bonuses on wins, and be allowed to keep all prize money. None of them would have to work on their motorcycles—Thuett and Carruthers would take care of that— and their air fares and expenses to and from the races would be paid by Yamaha. Such generosity was another thing that helped earn Schick his “Godfather” nickname, but generosity was actually the last thing on Shick’s mind. He’d done a cost-cutting survey and discovered it was more economical to run the team this way. It also allowed the riders time to concentrate on one thing, winning.

Now Schick had the riding and mechanical talent he needed to seriously challenge the Grand National Champion, but no new motorcycles. Racing development had lagged, and the machines Yamaha was forced to field in 1973 were the same slow ones from 1972. Schick put in a bid to have Yamaha of Japan build bigger time by dazzling the opposition. All Team Yamaha bikes were painted yellow and black, as were the clothing and leathers of the riders and mechanics. Canvas chairs were painted up with each rider’s name neatly inscribed on the back, Holly wood-style, and the transport vans were painted that way too. The whole dazzling entourage was plunked down in the middle of the Houston Astrodome at the opening Grand National of 1973, and Schick waited.

Amidst all of the dazzle, no one seemed to notice that the Yamahas were the same slow bikes of the year before. Rather, the team exuded a look of power and professionalism that almost scared the opposition away. Schick knew he was on the right track when during the racing season both Mert Lawwill and Gene Romero approached him about coming to work for Yamaha. So did other top-ranked riders.

There were other changes on Team Yamaha. Gone, for instance, was the “do your own thing” attitude of past years, and replacing it was discipline. Long hair was prohibited (when Kenny Roberts’ young buddy Skip Aksland, a top Novice class dirt track racer, asked Schick for some spare parts, Schick told him to get a haircut first). Roberts and Castro were expected to attend press and public relations functions, and to show up in suits and ties. “It was very important,” Schick says, “that the press should think of the Yamaha riders as the guys in the white hats. We were determined to build that image.”

Roberts won at the Astrodome. Then the late Jaarno Sarrinen won Daytona with Kel Carruthers (mixing his mechanical duties with riding duties), 2nd. Jim Evans on a private Yamaha was 3rd. In the dirt and road races that followed, Roberts picked up more than enough Grand National points to clinch Number One and give Yamaha the long-soughtafter manufacturers’ title. And Karsmakers won for Yamaha the motocross crown.

Winning, however, did not make Schick complacent. Now Yamaha’s powerful sales department wanted a third rider added to the team, backing up Roberts and Castro on the Grand National dirt tracks where they were facing upwards of 10 Harley-Davidsons. Finding a rider was no problem, Schick had dozens of names at his disposal. All he cared about was preserving the team’s winning edge and its harmony. He wanted Roberts and Castro to be in on the choice-making. Gary Scott was passed over because he was thought to be too controversial, Mert Lawwill was not taken for some other reason, and Gene Romero got picked. Schick presented him a one-year contract and told the former Triumph rider that he was to be the backup rider, and that Roberts was still the team’s star.

The choice was perfect. Although Roberts won another Grand National Championship in 1974, it was Romero who helped gain the points that gave Yamaha its second manufacturers’ title. Gene won two major Grand Nationals, rode one of the explosive new TZ700 road racers to three new speed records at Daytona, and finished 1974 the 3rd-ranked rider in the U.S.

Now in the middle of its third year under Schick’s direction, Team Yamaha seems looser, a bit more relaxed. Roberts’ hair now covers his ears, as does Schick’s. But it would be a mistake to think that Pete Schick is easing up. Accused of being a perfectionist, Schick says, of course he is. “This isn’t some game we’re playing,” he said recently, “it’s a business, a very serious business. We’re sending three kids out on the track to race at 170 mph. And if that isn’t serious, I don’t know what is.”

Yamaha is in racing to win, Schick continues, but defeat is not so terrible for him to take if it was unavoidable. Avoidable mistakes drive Schick up the wall. At a Northern California dirt track at Golden Gate Fields in 1973, an improperly-tightened nut loosened on the rear wheel of Kenny Roberts’ bike, allowing the wheel to come off. Roberts fell and lay in the track for a long time. After Schick examined the bike, he tongue-lashed mechanic Shell Thuett unmercifully. That was unnecessary, since the veteran tuner was himself devastated by his mistake. But ever since then Schick has roped off the Yamaha pits and is reluctant to allow anyone to come past the rope, including journalists and photographers. “If a mechanic is busy working on a bike, and somebody comes up to ask him questions or take his picture, it’s distracting, even dangerous,” explains Schick. But one of Schick’s critics says: “That’s about the only thing Schick really does at the races—chase people out of the Yamaha pits.”

Schick seems a cool customer, his dark eyes usually hidden behind his sunglasses. He doesn’t covet publicity, unless it is publicity for Yamaha, and considers himself a behind-the-scenes personality. He doesn’t, for instance, talk of the scores of promising young riders he’s helped through the years with free parts and advice (in spite of his reputation for saying no). Nor does Schick speak of the many development projects in the area of motorcycle safety and competition that he’s initiated as Yamaha’s R&D man. Only once, in fact, have I seen Pete Schick lose his famous cool—and it was when I mentioned that “chasing people out of the pits” comment to him.

(Continued on page 105)

Continued from page 82

He did not show anger, but from the slow, deliberate way he phrased his words, I could tell he was feeling it. “Before the world’s critics are so quick to criticize,” he said, “perhaps they’d like to try my job for a season. Or even a month. I mean it. I’d be happy to let them try. I’d welcome a short respite from the pressures of big business and world competition.

“What some people don’t realize,” Schick continued, “is that going to the races is like a vacation for me. It’s the least of my worries.”

And then he gave me a word picture of his job that few people who see him only at the races are aware of. It’s a go-go-go world of seven-day work weeks back at Yamaha, of fighting the inevitable internal corporate battles of budget, and personnel, and still running his department. Planning for the next racing season begins in September, and so does preparation of contracts, budgets, schedules and logistics. Moving masses of people and large quantities of equipment back and forth across the nation, as well as halfway around the world to various races, is exhausting. Squeezing the last nickel out of a corporate budget and making it pay accounts for much of the gray in Pete Schick’s hair.

Schick is well versed in the techniques required to put forth a winning effort. His background in motor sports competition is extensive, and he has been actively involved in motorcycling for more than two decades. He also built and raced his own drag strip machines in Northern California and raced sports cars. He was born in Lockport, New York, but reared in California. During his college days at Northern California’s San Jose State, he thought about a career in medicine, then lost interest after passing a summer as a hospital intern. He opted for a business degree instead. Before joining Yamaha in 1964, he worked for Standard Oil of California. “Me and 500 other bright young guys all making $600 a month and thrashing it out trying to fight to the top of the corporation. I hated it.” Today Schick seems to have the knack for hiring the right people and getting them working together as a team. It’s that simple. He says he borrows the philosophy of Roger Penske and George Bignotti of Indianapolis 500 fame. That philosophy seems to be: hire the best, and keep them happy by paying them well.

Making sure the Team Yamahas are fine-tuned and get to the races on time is only part of Schick’s job. Like a boxing manager, or the owner of a savage breed of racing cars called sprint cars, Pete Schick likes to keep his riders: Roberts, Romero and > Castro fine-tuned as well. He likes to get inside their heads and learn what makes them tick.

He believes he knows them well, these superstars he calls his “kids.”

“Kenny,” he says, “won’t let you break into his thoughts before a race. He’s an excellent listener, though. And although he gives the impression of being extremely nonchalant, he’s actually tighter than a tick. He likes to take a corner on a road course and diagram it in his mind the way we used to diagram sentences in English class. He’s also super-easy on equipment. In a race he doesn’t like any fancy pit signals or anything like that. All business, is what Kenny is.

“Gene,” Schick continued, “you need to keep your eye on before the start of a race. He gets awfully keyed up. You need to talk to him, keep him happy. But once the race starts, Gene’s your old steady veteran. He’s cautious in the beginning—knowing that’s when most accidents happen. He’s learned that through experience. But once he settles down and gets running, his lap times get faster and faster. He finishes harder than any rider out there.”

And Don Castro?

“Donnie is awfully high-strung. He’s a top rider, an outstanding rider, one of the best that the U.S. has, but has almost no self-confidence. I don’t know why that is. Donnie is a guy who always needs encouraging.”

The slightly-built Castro breaks easily too—Schick learned that fact last year at a dirt track race near San Diego, California. Castro fell and badly damaged his knees. He missed four months worth of races and still wasn’t fully healed when he did return. His accident brought about the edict from Schick and Yamaha that team members no longer were to compete in so-called “lollipop races” with small purses and no National significance. At that, Schick could have replaced the injured Castro on the team with a healthy rider, as Norton-Triumph did this year to injured Mike Kidd. But Schick refused. “I couldn’t do that to Donnie,” he said.

Team Yamaha survived 1974 without Castro and still won the manufacturers’ championship, but whether they would have been able to without Kenny Roberts is doubtful. And so it is whispered in racing that Roberts is Pete Schick’s security blanket, and that if Roberts should ever leave Yamaha, Schick’s own job would be in jeopardy because Yamaha would stop winning.

There’s no denying that Schick likes to keep close tabs on Roberts at all times, and even something so minor as a sprained thumb—which Roberts suffered while racing in England last winter—can alarm Schick.

And then there was the Italian episode during last year’s Imola 200-mile race. At 3 a.m. on race morning Schick was awakened by Roberts, Romero and the British rider Barry Sheene pounding on his hotel door. Kel Carruthers was with them. Carruthers looked grim, but the three riders were giggling. Schick looked closer and saw that all three were sopping wet and disheveled. And they were giggling because they were in shock.

(Continued on page 106)

Continued from page 105

Roberts nodded for Carruthers to tell Schick what had happened. Roberts had gone and gotten Carruthers first so that Kel would be the one to have to break the news to Pete.

The news was that the Fiat rental car in which Roberts, Romero and Sheene had been driving—and which had been leased in the name of Yamaha’s European race chief Rod Gould—was at that moment under four feet of water in an Imola canal.

While out joy-riding, one of the trio—no one would say who was driving-had lost control and flipped the little car into the drink. Once in the water, the three riders had to swim for their lives.

Schick wanted to blow his stack. Instead he counted to 10. “All three of those idiots could have been wiped out in the deal,” he said. “What they’d done, fooling around like that, was insane. But I couldn’t stay mad at them. They were laughing and carrying on, but it was all an act. Underneath it all, they were scared to death.”

And then he learned that Roberts’ helmet, boots, gloves and racing leathers were still locked up in the Fiat’s trunk. Schick decided to teach Roberts a lesson. “I took the little boy out there again and made him go back down into that dirty murky harbor water, open the trunk, and get his leathers. He came up gasping for air. Did he learn a lesson from it? I hope so.”

As long as Team Yamaha continues to win races, Pete Schick stays happy. But 1975 has so far been rugged. Schick lost his star motocrosser, Karsmakers, to Honda when Honda offered more money. Corporate budget slashes forced the dissolution of Yamaha’s dirt track team, and Romero and Castro were contracted for road races only. Only Kenny Roberts was left as a fully-sponsored Yamaha racer, and in July, following a spill at Castle Rock, Washington, Roberts had dropped more than 200 points behind Gary Scott in the annual chase for Number One.

And yet Schick seemed confident that he could regroup, keep his Yamaha racing team going and start winning again. And who would doubt him? He’s The Godfather. @