RIDING HIGH

There's Still Room For Solitary, Grueling Adventure-Even In California.

LEE STANLEY

FIVE YEARS AGO, Clyde Howdy was traveling from Texas to Cali-fornia in a private airplane. As he flew over the Panimint Mountain Range, surrounding Death Valley in eastern California, he noticed an abandoned mining site high in the mountains at the 8000-ft. level. The pilot made a number of close passes over the area, and it seemed, from an aerial view at any rate, that it had not been disturbed since last “worked”—some 50 or 60 years ago. It appeared that the miners had just left one day and never returned. Tools lay scattered around the area; buckboards, ore carts, blacksmith equipment, per-sonal articles—all left behind as if to be used the following day. They never were.

Two years later, Clyde attempted to locate the lost mine. He spent two days with a companion in a four-wheel-drive jeep combing the foothills of the Panimint Mountains looking for the slightest hint of a trail. He found nothing. The last day, they drove deep into the foothills and attempted to climb the mountain but were forced to turn back time after time because of the deep gorges or natural walls formed by boulders and rocks. They returned to Los Angeles empty-handed and discouraged.

During the next few years, Clyde and I became very active in off-the-road motorcycle events, racing, touring and exploring. Each time out on our motorcycles we were further assured of their extreme flexibility and practicality. With proper gearing and tires they could tackle the roughest terrain and, because of their light weight, could be manhandled over rocks and gorges. Their low gasoline consumption gave them a tremendous range. Clyde felt they would be perfect transportation for locating the lost mine.

We quickly made plans for the trip, including Paul Williams in our outing. He had a taste for adventure and the unknown, and knew how to handle a motorcycle in extremely rough terrain. The three of us left Los Angeles in Clyde’s half-ton pickup, loaded down with our motorcycles, tow lines, spare parts, and enough food, water and gasoline to last a week. By midday we reached Darwin, Calif., and began to branch out on a dusty, dry, dirt road for about 10 miles—the same road Clyde had followed before. The deeper we headed into the desert, the more side roads branched from the main. Finally the trail diminished into a dry riverbed. Another five miles in, we left the dried wash and made camp near the foothills.

It was a beautiful sight, with the magnificence and grandeur only the empty desert can afford. The stillness and vastness were amazing. By early evening the campsite was in order. We unloaded our motorcycles, filled them with gas, put packs on our backs and headed into the desert along the wash away from the campsite.

In the area we were exploring, the base of the mountain was guarded by a 30-foot ledge that kept our bikes from climbing. Rather than continue along to the end of the ledge, another eight or 10 miles, Clyde decided to climb it by foot to see if once on top he could determine which direction to travel.

Paul and I remained at the base as Clyde began the arduous task up the face of the ledge. The footing was uneasy, and one mistake would have sent him tumbling back to the ground. We watched as he inched his way to the top, occasionally sending small rocks and sand crashing to the ground. Finally he neared the top. Just as we thought he would climb over the ledge, he froze.

A rattlesnake stared him in the face, its rattle vibrating furiously in the air, its tongue darting about madly. Clyde’s instant reaction was to pull back. In doing so, he almost lost his balance, which would have sent him plummeting to the ground. His footing was too unstable to drop down quickly out of reach of the rattler, and there was no possible way to go around it. So he froze, face to face with the snake, and waited it out. Clyde felt he stayed motionless for at least three hours, but in fact it was about 20 minutes. Then, the rattles stopped vibrating, and the snake searched the air with its darting tongue and very slowly started to wind away from Clyde.

The sun was beginning to set and the tension Clyde had faced left him absolutely exhausted, so we decided to head back to camp. We had seen no trace of the mine.

The evening began to get chilly as the sky turned dark grey and outlined the distant mountains. The still air began to fill with faint, distant sounds as the desert came alive with the protection of nightfall. We unrolled our sleeping bags, threw a few pieces of wood on the now low camp fire and bedded down. The stars slowly began to appear in the black, and my imagination started to take over. Shapeless forms identified themselves as my eyes adjusted to the dark. The wind picked up its constant howl, and the air became crisp and sharp. As I dozed off I heard the mountain, squatting defiantly in the distance, secretly laugh at our prospective adventure. But as I concentrated on the sound, it disappeared.

We were up with the sun, secured enough firewood to cook a hearty breakfast, organized our gear, wiped the dew off our bike seats and headed out once again on our trail toward the mountain. We went the distance past the ledge we had discovered the day before and began to search the floor of the desert for traces of a footpath.

Fifteen miles distance in the country or 15 miles into a wooded area is usually, at best, exciting. But 15 miles into the desert away from your campsite, which is another 15 miles from the nearest paved road, can be very dangerous. We saw no signs of humans or signs that humans had ever been in the area. The sun was beginning to get very hot, and the sand and dust found their way into our lungs. My mouth was dry, my voice raspy and my legs were tired. The terrain was very rough, and we were unable to maintain any speed. We had to shift gears constantly and walk our bikes through fields of boulders and irregular rock formations. Two gorges that had been formed by flash floods forced us to dismount our motorcycles and hook up rope pulleys to lower them individually to the bottom. We would lower one man down with the bike, and whoever was the victim had to climb up over the other side with the rope tied around his waist. Assured that we could scale the other side, the remaining two would lower the other bikes into the gorge; then one would join the other on the opposite side. First, we would haul out one bike, then another and then the third. Then we would haul out the last man in the gorge. Apparently we were climbing very gradually, because we didn’t notice an increase in altitude. But even this slight amount of effort was very exhausting. We continued slowly along the foothills and made our way toward the base of the mountain.

As we looked down into a wash that led from the mountain, the sun reflected the gold dust that had been washed down out of the hills. We still had no idea of the mine’s location. Hundreds of square miles lay stretched out before us. As far as the eye could see, desert scenery repeated itself. And here, in the middle of the desert wasteland, we found ourselves faced with the same problems prospective miners had been faced with a hundred years before us—except we knew the mining camp existed, and we had efficient transportation.

At the foot of the mountain was gold dust. Where did it come from? “Follow the wash leading into the mountain.” Clyde knew the gold dust had been washed down out of the mountain during the rains. Why not follow the gold dust back into the mountain, hoping it would lead us to the “mother lode” or quartz vein it originated from? A few miles farther along we noticed a heavily stoned area which cut into the central basin. It was too rough and irregular to see “dust,” but it seemed more like an abandoned road than a wash. We followed it. The going got rough as the road became less and less distinct and more rocky, until there was no longer any sign of a road. Just rocks strewn about, lining their way into the mountain.

Five miles farther, riding became almost impossible. The elevation, we judged, was close to 7000 ft. above sea level, and I began to notice a shortness of breath as a result of less oxygen. While riding over the rough country, we had no time to take our eyes away from what was immediately in front of us. When we stopped for water, I was astounded by the distance we had covered and the height we’d reached. The basin we had so carefully followed lay 3000 ft. below and 15 miles away.

“This whole area looks familiar.” Clyde remembered the view from the plane and it all began to take shape.

“Everything looks different from the air,” I reminded him, but he was determined that we were approaching the mining site.

We continued up the mountain. I began to get excited with the possibility of discovery, and it showed in my riding. I couldn’t catch my breath. Then came a beautiful sight, tucked there in the side of the mountain, deep in a ravine.

On my right was a line of stone foundations where once stood the homes and tool sheds of the miners. The winds and rains had torn them carelessly to the ground, bleaching the wood grey-white and dry. Only one building remained standing. It was made completely of stone, save the roof frame, and it had survived the punishing years of heat, flash floods and landslides. We were all bursting with the renewed energy of discovery. We frantically began to search the grounds, discovering one thing and immediately having our attention directed toward something more exciting. The surrounding grounds near the foundations were covered with personal articles and tools. I found a pair of children’s shoes, not 10 feet apart, baked dry by the sun, but still perfectly intact. The garbage heap, composed of rusted cans that had been opened not by a can-opener but by the blade of a knife, was undisturbed. Looking closer, I discovered bottles so old they had been reshaped, their broken edges worn smooth by sandstorms. Some still were sealed by corks, and one contained a red-orange substance.

Everything was just as I had hoped. Old buckboards lined the hill at the edge of the mine opening on the other side of the ravine. Tools, scattered around to be readily available for use, now lay rusted and bleached. Clyde found an old cast iron stove showing above the ground. He dug down and discovered it to be in very good condition.

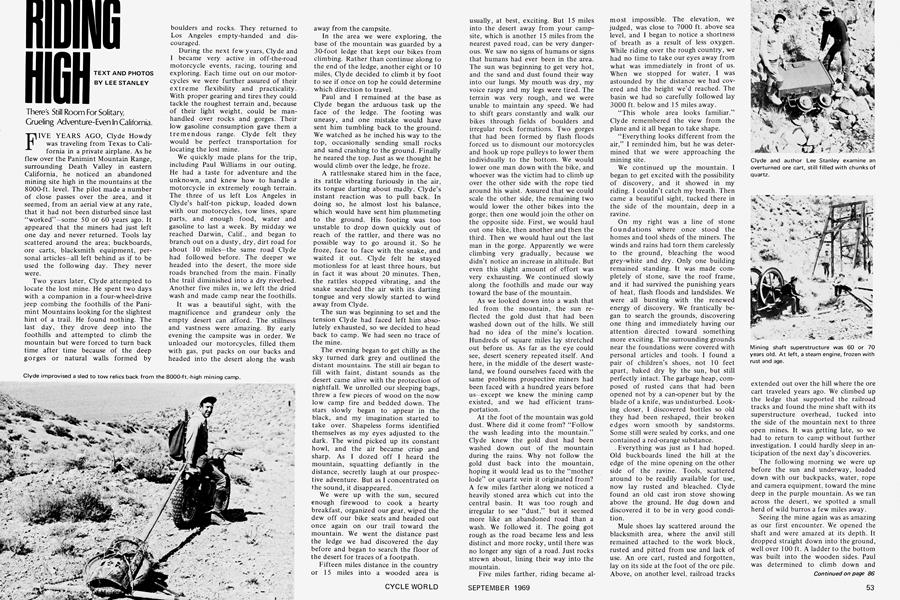

Mule shoes lay scattered around the blacksmith area, where the anvil still remained attached to the work block, rusted and pitted from use and lack of use. An ore cart, rusted and forgotten, lay on its side at the foot of the ore pile. Above, on another level, railroad tracks extended out over the hill where the ore cart traveled years ago. We climbed up the ledge that supported the railroad tracks and found the mine shaft with its superstructure overhead, tucked into the side of the mountain next to three open mines. It was getting late, so we had to return to camp without further investigation. I could hardly sleep in anticipation of the next day’s discoveries.

The following morning we were up before the sun and underway, loaded down with our backpacks, water, rope and camera equipment, toward the mine deep in the purple mountain. As we ran across the desert, we spotted a small herd of wild burros a few miles away.

Seeing the mine again was as amazing as our first encounter. We opened the shaft and were amazed at its depth. It dropped straight down into the ground, well over 100 ft. A ladder to the bottom was built into the wooden sides. Paul was determined to climb down and

Continued on page 86

Continued from page 53

investigate, but realized the danger when he easily pulled off the first rung of the ladder.

Overhead, a handmade chain with a hook at the end dangled freely. Apparently, it was lowered down into the bottom of the shaft to haul buckets of ore to the surface. The links had almost been worn through at the points of coptact.

Near the mine shaft, a few yards away, an old steam engine lay rusted solid. I couldn't determine whether the engine was used to haul the ore buckets out of the mine shaft or whether it was used to grind the quartz so it later could be separated from the gold. But most amazing was contemplating how the miners got this tremendous hunk of cast iron over such rough country and up into the mountain! And what did they use for a water supply to power the giant engine? There were no streams, nor broken water barrels that might have been brought up by mule teams. Three mines were dug into the side of the mountain near the mine shaft. I later learned that this was quartz mining. A miner would follow a "gold vein" from the surface and dig deep into the sides of the mountain to obtain the gold and separate it f~om the quartz.

I began to follow one of the mines into the mountainside. I was no farther than 15 feet when I heard th~ feverish rattle of a snake. Chills raced up my legs and laced across my back. I stared into the dark passage before me. I knew I shouldn't move, but the crawling shiver of panic started my legs trembling and, unable to resist, I leaped uncontrollably backward, then turned and raced out toward the blinding light. I lunged out into the open air and crashed into Clyde. He stopped me, but knew without asking what had happened.

We began to load our treasures into our packs and rigged up ways to get larger pieces back to camp. I had tajen the chain that was over the mine shaft, along with a "single tree" off a buckboard, a dozen mule shoes, railroad spikes and other odds and ends, while Clyde and Paul concentiated on recovering parts of the old iron stove, a handmade shovel, and an eight-foot "tongue" from a buckboard.

I have to hand it to Clyde. He accepted many insults from us when he told us he was planning to bring back the tongue. The way he planned to haul this monster back to camp by motorcycle, along with an additional 75 lb. of cast iron and scrap, seemed impossible. Within a half hour he rigged up the neatest little sled I have ever seen and proceeded to haul the whole thing back to camp over some of the roughest country in California—and he broke down only twice.

We had to move at a snail’s pace because of the awkwardness of Clyde’s relics. There were many times when Paul and I had to dismount and carry the sled over very rough terrain and lower it into the gorges. I had secretly wished throughout the return trip that the sled would collapse and Clyde would be discouraged, but it never happened.

The closer I got to our campsite, the faster I would ride and the more my back pack would bounce and cut into my throbbing shoulders. The exhaustion, heat and pain were dulling my senses, and I lost my timing and crashed in a sand wash. I was not hurt but regretted our decision not to wear safety helmets during the outing.

We had decided that with the extremely high temperatures and the sun beating down on us, helmets would only make us dizzy. But it would have been a much better alternative than ending up next to a rock. As I centered the pack on my back and righted my motorcycle, I noticed my hands were shaking from the experience.

I pounced on the kick starter. Nothing happened. Again and again. The engine wouldn’t pop. The sand was so soft and deep I couldn’t jump start the bike, so I pushed it out of the wash and along the ground for about a hundred yards. My legs turned to rubber, my throat was parched and scratchy from the dust in my lungs, and I was beginning to feel sorry that I had struck out on my own. Finally, I laid my bike down in the sand and rested.

The longer I waited, the more tired I became, so I got my tool kit from the pack, pulled the spark plug from the engine, cleaned and dried it, replaced it and jumped on the kick starter. The engine started to moan and I had to lean the bike way over to its side to fire it up. It caught. I jumped aboard and carefully made my way back to camp.

After I returned to Clyde and Paul, it took us almost four hours to get everything back to camp. By the time we arrived, I felt that the worth of each discovery had tripled in value. Our voices sounded metallic and it became an effort just to talk. Our mouths were dry and swollen from the heat and dust.

We secured the last motorcycle in the back of our pickup and jumped into the cab. Clyde jerked the truck into gear and started toward the main road, 15 miles away. I took one last look over my shoulder back into the desert and found myself laughing at the mountain we were leaving behind. But as I concentrated on the sound of the engine, my laughter disappeared and the air behind us was suddenly filled once again with a tremendous hollow.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

September 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

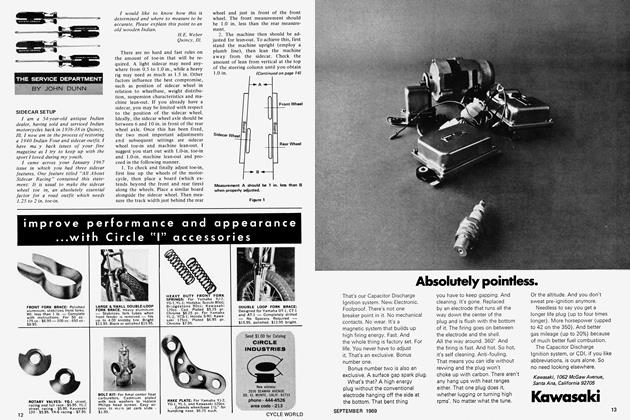

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

September 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1969 -

Competition

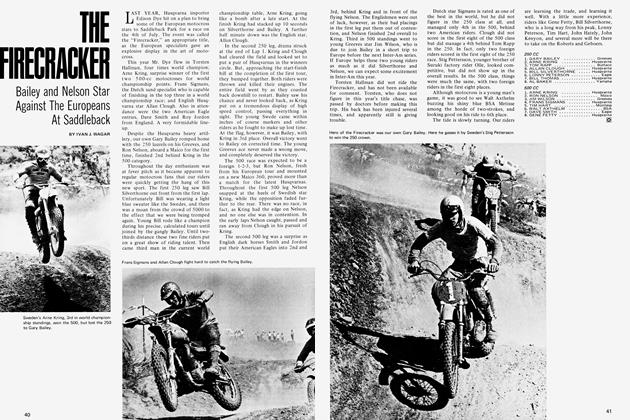

CompetitionThe Firecracker

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

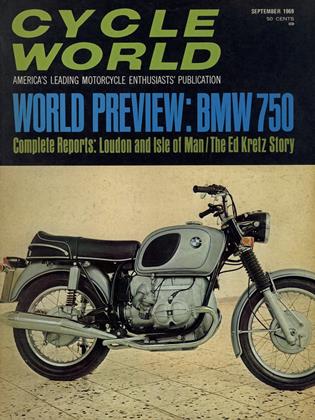

Preview

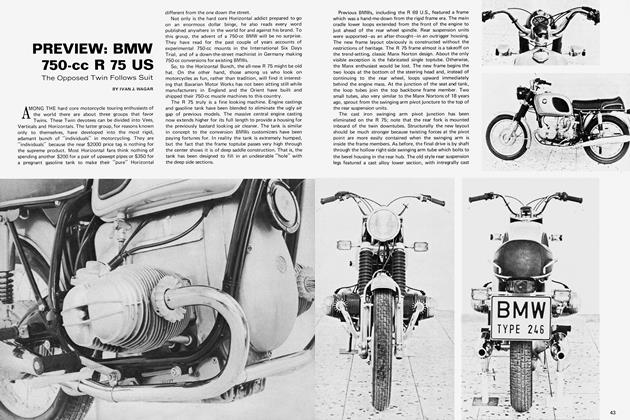

PreviewBmw 750-Cc R 75 Us

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar