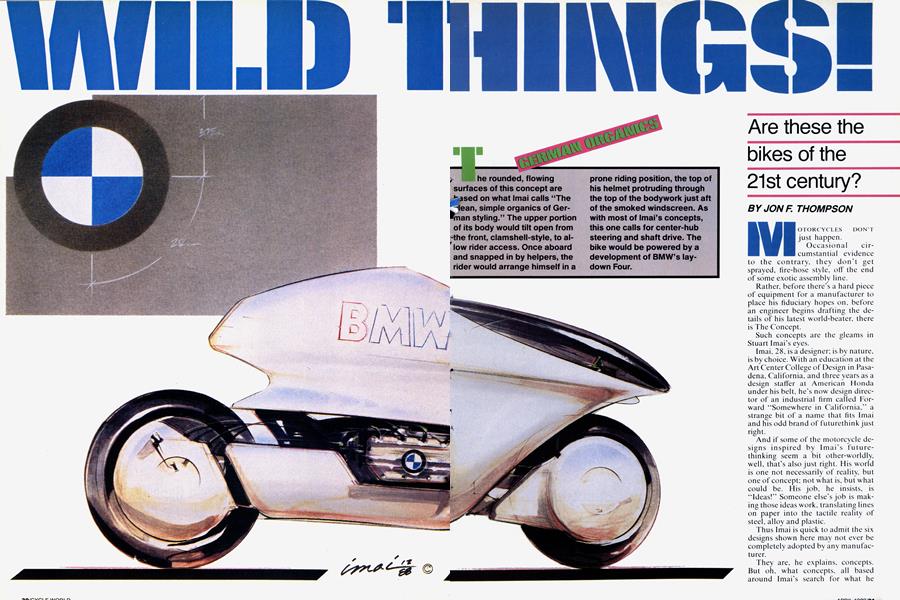

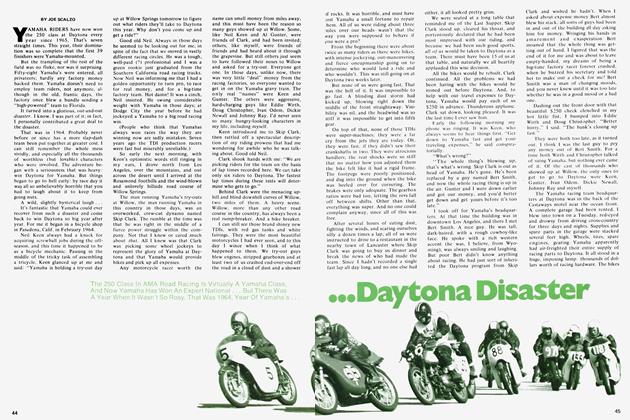

WILD THINGS!

GERMAN ORGANICS

The rounded, flowing surfaces of this concept are based on what Imai calls “The clean, simple organics of German styling.” The upper portion of its body would tilt open from -<the front, clamshell-style, to allow rider access. Once aboard and snapped in by helpers, the rider would arrange himself in a prone riding position, the top of his helmet protruding through the top of the bodywork just aft of the smoked windscreen. As with most of Imai’s concepts, this one calls for center-hub steering and shaft drive. The bike would be powered by a development of BMW’s laydown Four.

Are these the bikes of the 21st century?

JON F. THOMPSON

MOTORCYCLES DON’T just happen. Occasional circumstantial evidence

to the contrary, they don’t get sprayed, fire-hose style, oflf the end of some exotic assembly line.

Rather, before there’s a hard piece of equipment for a manufacturer to place his fiduciary hopes on, before an engineer begins drafting the details of his latest world-beater, there is The Concept.

Such concepts are the gleams in Stuart Imai’s eyes.

Imai, 28, is a designer; is by nature, is by choice. With an education at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California, and three years as a design staffer at American Honda under his belt, he’s now design director of an industrial firm called Forward “Somewhere in California,” a strange bit of a name that fits Imai and his odd brand of futurethink just right.

And if some of the motorcycle designs inspired by Imai's futurethinking seem a bit other-worldly, well, that’s also just right. His world is one not necessarily of reality, but one of concept; not what is, but what could be. His job, he insists, is “Ideas!” Someone else’s job is making those ideas work, translating lines on paper into the tactile reality of steel, alloy and plastic.

Thus Imai is quick to admit the six designs shown here may not ever be completely adopted by any manufacturer.

They are, he explains, concepts. But oh, what concepts, all based around Imai’s search for what he calls “new proportions,” and around Imai’s strongly held central notion that Motorcycling, The Activity, should become more visible.

You can hardly get more visible than the Indianapolis 500, that selfproclaimed Greatest Spectacle in Racing, that feast of speed held every Memorial Day. So Imai has designed six futuristic machines he calls Indybikes, each using design themes characteristic, he believes, of those currently being expressed by the manufacturers. The idea is that each manufacturer would build a machine to Imai’s design to be used as a promotional tool. The bikes would then perform exhibition lappery at Indianapolis and other high-visibility motorsports events, the better to get the general concept of motorcycling, not to mention specific manufacturer names, directly before the eyeballs of those on hand and those watching via video links.

“They’re rolling, motorized billboards,” Imai enthuses.

That, at least, is the concept. Actualizing this concept would seem some ways away. But that may not be of paramount importance. To Imai, remember, the idea’s the thing.

The renderings on these pages are, he insists, image sketches which illustrate possible styling themes for realworld designs. The whole purpose of presenting designs that might not be entirely feasible for use in the real world, or which might not be possible from an engineering point-of-view, Imai believes, is that. “Without that step, the creativity is automatically dropped. A lot of blue-sky stuff stays out in the sky, but portions of it can be pulled down to reality.”

The first step in bringing the designs you see here from the blue sky into reality, he says, would be to perform what he calls a packaging exercise in which complete, full-sized wooden mockups would be built—a step which has not been taken and for which there is no schedule.

Just how unconventional are Imai’s futurebikes? Well, forget everything you know about traditional motorcycle layout, about the standard relationships between wheels, seats, tanks, fenders, etc. Also, forget what you know about conventional riding positions and conventional motorcycle construction.

Imai proposes a whole new deal.

SUZUKI

OPEN-AND-SHUT SUZUKI

This one is open and enclosed at the same time. It allows the rider to be seen," says Imai of his concept Suzuki, and indeed, the bodywork of this proposal does seem to shout th~~at less is more. The center-hub steering lmai pro poses for this machine is clearly visible in his rendering, and so is its BMW-like single-sided swingarm, which incorporates shaft drive. For power, Imal pro poses a 700cc development of Suzuki's two-stroke Gamma en gine.

For starters, the chassis of most of these bikes would be based upon unitized carbon-fiber pods, or tubs, the way the chassis of Indy cars are based on tubs of the same material. Chassis parts and mechanical components would then be bolted to reinforced sections of those tubs.

But that isn’t all: Imai is not at all shy about his affection for the Honda Helix scooter, that two-wheeled apparition which matches strange looks with a user-friendly personality and which works, by all accounts, including Imai’s, wonderfully well. And he’s not shy about the Helix’s influence upon his thinking, an influence deepened, he says, by three roundtrips between Los Angeles and Monterey, traveling up California’s scenic Highway One, on one of the things.

Thus, while several of his designs feature a prone, hands-forward-feetback riding position, with the rider’s weight supported on his chest and abdomen—Imai insists these designs do safeguard the family jewels against, er, devaluation—others employ Helix-like, feet-forward riding positions because, Imai believes, “It's a very natural way of sitting, as opposed to leaning forward on a sportbike. It’s an easy-chair-type configuration and it’s extremely comfortable. Plus, it helps give me the ergonomics and the new proportions I'm looking for.”

GREEN-TIRED TWIN

Imai’s Kawasaki concept continues his affection for shaft drive, center-hub steering and rounded shapes enclosing near-prone riding positions, but with two interesting differences. For show, there’s the bike’s green front tire, important, Imai believes, not only as a styling element but as an experiment in securing V-ratings for pigmented rubber. For go, Imai proposes a vertical Twin of about 700cc developed from the EX500 engine because, he explains, “Twins have character.”

FLAT-OUT FLYER

For his Yamaha design, Imai has chosen a riding sition which calls for the ri stretch out atop the machi his hands and elbows ahead of his body, and his feet and knee behind, with the major portion c his body weight supported mostly by his chest, which would rest upon the machine’s fuel tank. This concept’s )t’s styling stylinç draws from what Imai considers consider« “the typical Yamaha look,” ook,” which centers, he says, s, around around the look of the bike’s frame frame and and engine. For power, Imai proproposes a Four which would jld be be a a 70Qcc development of Yamaha’s current Genesis-se>nesis-s< ries engine.

New proportions, indeed; an Imai watch-phrase. Proportions so new, in fact, that the bodywork which encloses the suspension and mechanicals of Imai's Indybikes embraces the tilt-up concept found on drag-race funnycars: Tilt 'em open, climb aboard, tilt 'em closed.

The difference, though, is that the helmets of funnycar drivers don’t stick through the top of funnycar bodywork. The helmets of the riders of Imai’s designs would extend through the top of his bodywork. Imai explains, because, “If proportion and seating position are not pushed to the max I don't think you can get full use out of creative design. This is riding translated into design, but with that wind-in-the-face element.”

Imai’s imaginative designs might be just a little disappointing if lifting their respective tilt bodies revealed conventional motorcycle components. But his proposed components are anything but conventional, with most of his designs calling for centerhub steering and single-sided swingarms, though with Honda controlling >

V-THREE OUTRIGGER

This fully-enclosed design calls for recumbent seating and, like some of Imai’s other concepts, outriggers that would deploy at low speeds to stabilize the bike. Bodywork would tilt forward for rider access, with the axis of tilt being the machine’s front axle. The bike would be powered by a 700cc V-Three, a configuration Imai believes is reasonable to expect from Honda and a size he believes is capable of producing all the horsepower any of designs are likely to require.

INTEGRATED HOG

A shaft-drive Harley? can bet the hog farm one exists, at least in Imai’s imagination, where it would look like this and would be powered by—what else—an evolution of the current Evolution V-Twin. Imai describes this concept as “Having the typical H-D fenderto-gas-tank-to-seat relationship, but with a more integrated look than offered by current Harleys.” Imai would use disc wheels for their custom look, and he says of this concept, “If you give people something they’re used to seeing along with something that’s new— kind of a combination of both— it’s much easier to swallow.”

the design patents to the now-moribund ELF race bikes that did the most to make those designs visible, it may be difficult to visualize anyone but Honda actually bringing them into being, either on streetbikes or on prototypes.

Such alternative suspension systems particularly interest Imai, both in terms of design and in terms of materials. He believes that in the nottoo-distant future, plastics will become the material of choice for suspension components. Because of that belief, he’s designed, in conjunction with a Japanese engineering firm he’s unwilling to name, a motorcycle prototype based around a plastic suspension system. The prototype will feature what Imai calls “a new seating configuration” and extensive use of composite materials. “It won't be traditional, and it’ll be different from anything you see here,” he promises. Plans calí for a display-only prototype to be built for the show circuit this year.

Building for show, whether it’s the formality of the European exhibition circuit or the informality of the Saturday-night cruise, is what design is all about, Imai believes. Leaving the production of motorcycles solely in the hands of engineers might produce motorcycles that work very well, Imai says, “But you’d end up with boring, dry products. I think people want to be different, I think they want to stand out. The nice thing about riding something like a Bimota DB1 (with the Helix and the BMW Boxer, one of Imai’s favorite two-wheeled designs) is that you get noticed. It feels good to feel different from the crowd. A designer's role is to be able to meet market needs with fresh, new designs that stimulate the public and educate it in new design technologies.”

Stuart Imai’s designs certainly are noticed, certainly stimulate interest. That’s just what they’re supposed to do, at least in part because Imai hopes any interest generated by his motorcycle designs will help designers like himself repossess the ability to guide motorcycle development.

Such design guidance, he believes, is the natural order of things, an order which somehow has lost its way.

“Motorcycles are going through their mid-life crisis,” he says,” with the negative coverage given them by the general media dictating their future.” Whether or not Imai’s designs are ever translated into the reality of alloy and plastic, a reality which will overcome any mid-life crisis with the greener pastures of full, vigorous maturity, remains to be seen. But what’s sure is that as long as there are thinkers like Imai around, thinkers who remain excited about motorcycling and all its possibilities, motorcycling’s future can only be bright.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSo Many Curves, So Little Time

April 1989 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeSilver Wing For A Silver Eagle

April 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsTen Percenters

April 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's Spada: the Newest World Standard

April 1989 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupHailwood Ducati For Sale: $19,000

April 1989