So many curves, so little time

UP FRONT

David Edwards

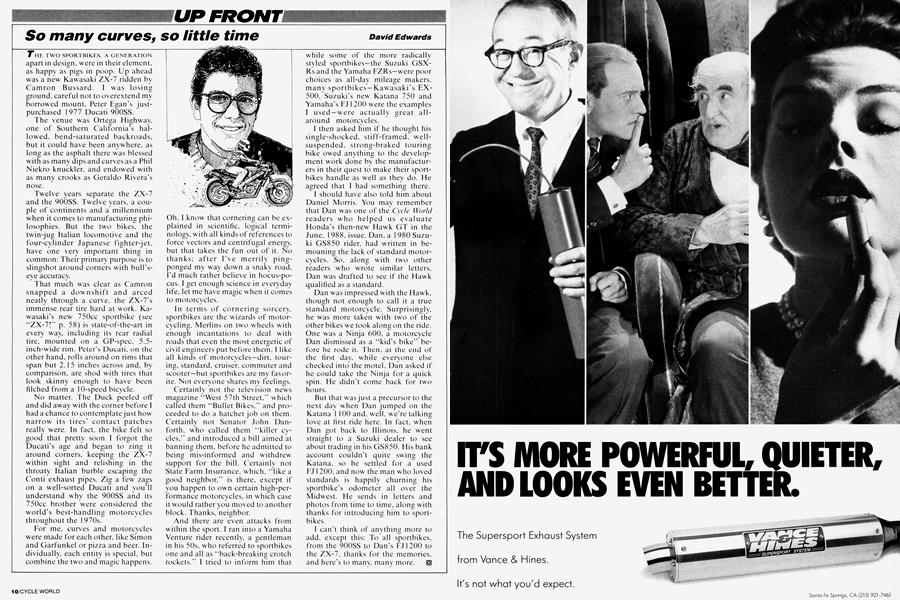

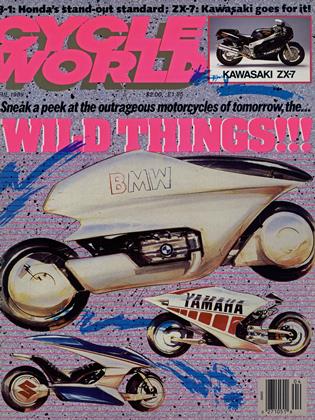

THE TWO SPORTBIKES. A GENERATION apart in design, were in their element, as happy as pigs in poop. Up ahead was a new Kawasaki ZX-7 ridden by Camron Bussard. I was losing ground, careful not to overextend my borrowed mount, Peter Egan's justpurchased 1977 Ducati 900SS.

The venue was Ortega Highway, one of Southern California's hallowed, bend-saturated backroads, but it could have been anywhere, as long as the asphalt there was blessed with as many dips and curves as a Phil Niekro knuckler, and endowed with as many crooks as Geraldo Rivera’s nose.

Twelve years separate the ZX-7 and the 900SS. Twelve years, a couple of continents and a millennium when it comes to manufacturing philosophies. But the two bikes, the twin-jug Italian locomotive and the four-cylinder Japanese fighter-jet, have one very important thing in common: Their primary purpose is to slingshot around corners with bull’seye accuracy.

That much was clear as Camron snapped a downshift and arced neatly through a curve, the ZX-7's immense rear tire hard at work. Kawasaki’s new 750cc sportbike (see “ZX-7!” p. 58) is state-of-the-art in every way, including its rear radial tire, mounted on a GP-spec, 5.5inch-wide rim. Peter's Ducati. on the other hand, rolls around on rims that span but 2.15 inches across and. by comparison, are shod with tires that look skinny enough to have been filched from a 10-speed bicycle.

No matter. The Duck peeled off and did away with the corner before 1 had a chance to contemplate just how narrow its tires' contact patches really were. In fact, the bike felt so good that pretty soon I forgot the Ducati’s age and began to zing it around corners, keeping the ZX-7 within sight and relishing in the throaty Italian burble escaping the Conti exhaust pipes. Zig a few zags on a well-sorted Ducati and you’ll understand why the 900SS and its 750cc brother were considered the world’s best-handling motorcycles throughout the 1970s.

For me, curves and motorcycles were made for each other, like Simon and Garfunkel or pizza and beer. Individually, each entity is special, but combine the two and magic happens.

Oh, I know that cornering can be explained in scientific, logical terminology, with all kinds of references to force vectors and centrifugal energy, but that takes the fun out of it. No thanks; after I've merrily pingponged my way down a snaky road, I’d much rather believe in hocus-pocus. I get enough science in everyday life, let me have magic when it comes to motorcycles.

In terms of cornering sorcery, sportbikes are the wizards of motorcycling. Merlins on two wheels with enough incantations to deal with roads that even the most energetic of civil engineers put before them. I like all kinds of motorcycles—dirt, touring, standard, cruiser, commuter and scooter—but sportbikes are my favorite. Not everyone shares my feelings.

Certainly not the television news magazine “West 57th Street.” which called them “Bullet Bikes.” and proceeded to do a hatchet job on them. Certainly not Senator John Danforth. who called them “killer cycles,” and introduced a bill aimed at banning them, before he admitted to being mis-informed and withdrew support for the bill. Certainly not State Farm Insurance, which, “like a good neighbor,” is there, except if you happen to own certain high-performance motorcycles, in which case it would rather you moved to another block. Thanks, neighbor.

And there are even attacks from within the sport. I ran into a Yamaha Venture rider recently, a gentleman in his 50s, who referred to sportbikes one and all as “back-breaking crotch rockets.” I tried to inform him that while some of the more radically styled sportbikes—the Suzuki GSXRs and the Yamaha FZRs—were poor choices as all-day mileage makers, many sportbikes —Kawasaki’s EX500. Suzuki's new Katana 750 and Yamaha’s FJ 1200 were the examples I used —were actually great allaround motorcycles.

I then asked him if he thought his single-shocked, stiff-framed, wellsuspended, strong-braked touring bike owed anything to the development work done by the manufacturers in their quest to make their sportbikes handle as well as they do. He agreed that I had something there.

I should have also told him about Daniel Morris. You may remember that Dan was one of the Cycle World readers who helped us evaluate Honda’s then-new Hawk GT in the June, 1988, issue. Dan. a 1980 Suzuki GS850 rider, had written in bemoaning the lack of standard motorcycles. So. along with two other readers who wrote similar letters, Dan was drafted to see if the Hawk qualified as a standard.

Dan was impressed with the Hawk, though not enough to call it a true standard motorcycle. Surprisingly, he was more taken with two of the other bikes we took along on the ride. One was a Ninja 600, a motorcycle Dan dismissed as a “kid's bike” before he rode it. Then, at the end of the first day, while everyone else checked into the motel. Dan asked if he could take the Ninja for a quick spin. He didn't come back for two hours.

But that was just a precursor to the next day when Dan jumped on the Katana 1 100 and. well, we're talking love at first ride here. In fact, when Dan got back to Illinois, he went straight to a Suzuki dealer to see about trading in his GS850. His bank account couldn't quite swing the Katana, so he settled for a used FJ 1200, and now the man who loved standards is happily churning his sportbike's odometer all over the Midwest. He sends in letters and photos from time to time, along with thanks for introducing him to sportbikes.

I can't think of anything more to add. except this: To all sportbikes, from the 900SS to Dan’s FJ1200 to the ZX-7, thanks for the memories, and here’s to many, many more.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

At Large

At LargeSilver Wing For A Silver Eagle

April 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsTen Percenters

April 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's Spada: the Newest World Standard

April 1989 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupHailwood Ducati For Sale: $19,000

April 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupDrag-Racing School Hits the Road

April 1989