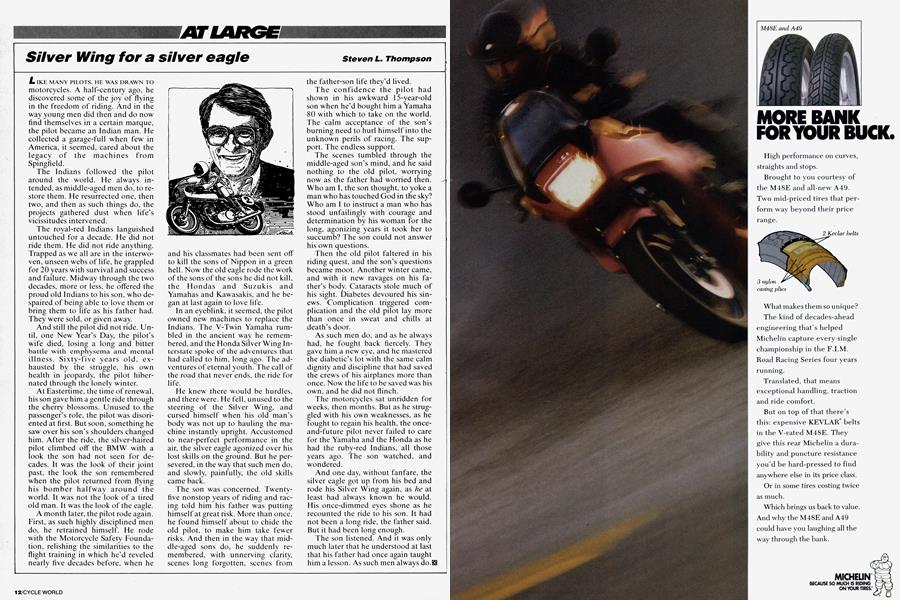

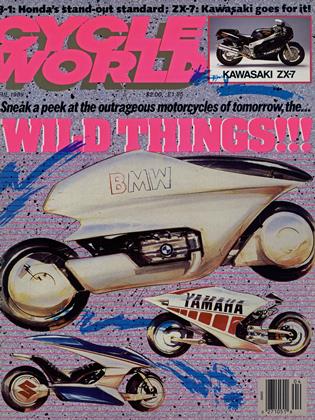

Silver Wing for a silver eagle

AT LARGE

Steven L. Thompson

LIKE MANY PILOTS. HE WAS DRAWN TO motorcycles. A half-century ago, he discovered some of the joy of flying in the freedom of riding. And in the way young men did then and do now find themselves in a certain marque, the pilot became an Indian man. He collected a garage-full when few in America, it seemed, cared about the legacy of the machines from Spingfield.

The Indians followed the pilot around the world. He always intended, as middle-aged men do, to restore them. He resurrected one, then two, and then as such things do, the projects gathered dust when life’s vicissitudes intervened.

The royal-red Indians languished untouched for a decade. He did not ride them. He did not ride anything. Trapped as we all are in the interwoven, unseen webs of life, he grappled for 20 years with survival and success and failure. Midway through the two decades, more or less, he offered the proud old Indians to his son, who despaired of being able to love them or bring them to life as his father had. They were sold, or given away.

And still the pilot did not ride. Until, one New Year’s Day, the pilot’s wife died, losing a long and bitter battle with emphysema and mental illness. Sixty-five years old, exhausted by the struggle, his own health in jeopardy, the pilot hibernated through the lonely winter.

At Eastertime, the time of renewal, his son gave him a gentle ride through the cherry blossoms. Unused to the passenger’s role, the pilot was disoriented at first. But soon, something he saw over his son’s shoulders changed him. After the ride, the silver-haired pilot climbed off the BMW with a look the son had not seen for decades. It was the look of their joint past, the look the son remembered when the pilot returned from flying his bomber halfway around the world. It was not the look of a tired old man. It was the look of the eagle.

A month later, the pilot rode again. First, as such highly disciplined men do, he retrained himself. He rode with the Motorcycle Safety Foundation, relishing the similarities to the flight training in which he’d reveled nearly five decades before, when he and his classmates had been sent off to kill the sons of Nippon in a green hell. Now the old eagle rode the work of the sons of the sons he did not kill, the Hondas and Suzukis and Yamahas and Kawasakis, and he began at last again to love life.

In an eyeblink, it seemed, the pilot owned new machines to replace the Indians. The V-Twin Yamaha rumbled in the ancient way he remembered, and the Honda Silver Wing Interstate spoke of the adventures that had called to him, long ago. The adventures of eternal youth. The call of the road that never ends, the ride for life.

He knew there would be hurdles, and there were. He fell, unused to the steering of the Silver Wing, and cursed himself when his old man’s body was not up to hauling the machine instantly upright. Accustomed to near-perfect performance in the air, the silver eagle agonized over his lost skills on the ground. But he persevered, in the way that such men do, and slowly, painfully, the old skills came back.

The son was concerned. Twentyfive nonstop years of riding and racing told him his father was putting himself at great risk. More than once, he found himself about to chide the old pilot, to make him take fewer risks. And then in the way that middle-aged sons do, he suddenly remembered, with unnerving clarity, scenes long forgotten, scenes from

the father-son life they’d lived.

The confidence the pilot had shown in his awkward 15-year-old son when he'd bought him a Yamaha 80 with which to take on the world. The calm acceptance of the son’s burning need to hurl himself into the unknown perils of racing. The support. The endless support.

The scenes tumbled through the middle-aged son’s mind, and he said nothing to the old pilot, worrying now as the father had worried then. Who am I, the son thought, to yoke a man who has touched God in the sky? Who am I to instruct a man who has stood unfailingly with courage and determination by his woman for the long, agonizing years it took her to succumb? The son could not answer his own questions.

Then the old pilot faltered in his riding quest, and the son’s questions became moot. Another winter came, and with it new ravages on his father’s body. Cataracts stole much of his sight. Diabetes devoured his sinews. Complication triggered complication and the old pilot lay more than once in sweat and chills at death’s door.

As such men do, and as he always had, he fought back fiercely. They gave him a new eye, and he mastered the diabetic’s lot with the same calm dignity and discipline that had saved the crews of his airplanes more than once. Now the life to be saved was his own, and he did not flinch.

The motorcycles sat unridden for weeks, then months. But as he struggled with his own weaknesses, as he fought to regain his health, the onceand-future pilot never failed to care for the Yamaha and the Honda as he had the ruby-red Indians, all those years ago. The son watched, and wondered.

And one day, without fanfare, the silver eagle got up from his bed and rode his Silver Wing again, as he at least had always known he would. His once-dimmed eyes shone as he recounted the ride to his son. It had not been a long ride, the father said. But it had been long enough.

The son listened. And it was only much later that he understood at last that his father had once again taught him a lesson. As such men always do.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSo Many Curves, So Little Time

April 1989 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsTen Percenters

April 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's Spada: the Newest World Standard

April 1989 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupHailwood Ducati For Sale: $19,000

April 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupDrag-Racing School Hits the Road

April 1989