Two-Up

AT LARGE

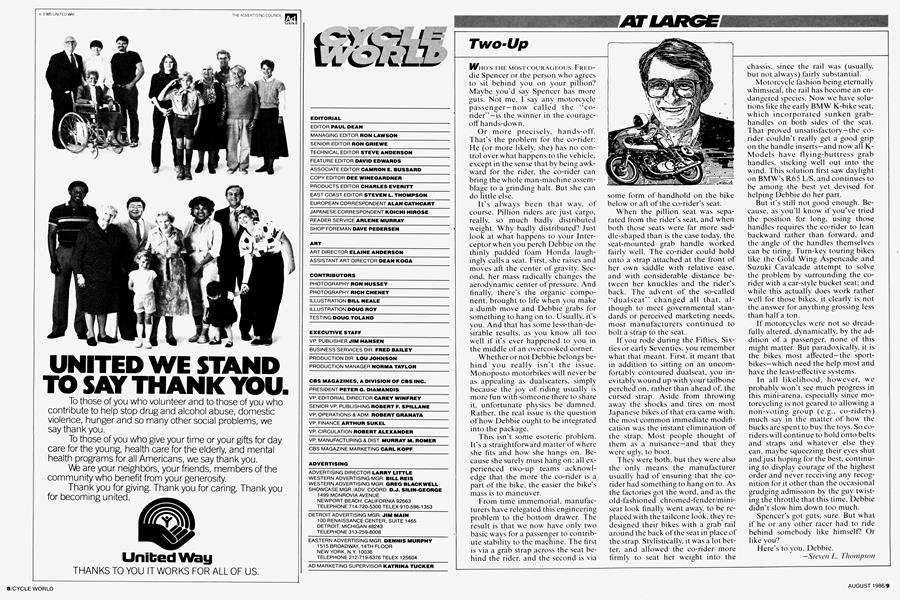

WHO'S THE MOST COURAGEOUS: FREDdie Spencer or the person who agrees to sit behind you on your pillion? Maybe you'd say Spencer has more guts. Not me. I say any motorcycle passenger—now called the “co-rider”—is the winner in the courage-off hands-down.

Or more precisely, hands-off. That’s the problem for the co-rider: He (or more likely, she) has no control over what happens to the vehicle, except in the sense that by being awkward for the rider, the co-rider can bring the whole man-machine assemblage to a grinding halt. But she can do little else.

It’s always been that way, of course. Pillion riders are just cargo, really, so much badly distributed weight. Why badly distributed? Just look at what happens to your Interceptor when you perch Debbie on the thinly padded foam Honda laughingly calls a seat. First, she raises and moves aft the center of gravity. Second, her mass radically changes the aerodynamic center of pressure. And finally, there’s the organic component, brought to life when you make a dumb move and Debbie grabs for something to hang on to. Usually, it’s you. And that has some less-than-desirable results, as you know all too well if it’s ever happened to you in the middle of an overcooked corner.

Whether or not Debbie belongs behind you really isn’t the issue. Monoposto motorbikes will never be as appealing as dualseaters, simply because the joy of riding usually is more fun with someone there to share it, unfortunate physics be damned. Rather, the real issue is the question of how Debbie ought to be integrated into the package.

This isn't some esoteric problem. It’s a straightforward matter of where she fits and how she hangs on. Because she surely must hang on; all experienced two-up teams acknowledge that the more the co-rider is a part of the bike, the easier the bike’s mass is to maneuver.

From time immemorial, manufacturers have relegated this engineering problem to the bottom drawer. The result is that we now have only two basic ways for a passenger to contribute stability to the machine. The first is via a grab strap across the seat behind the rider, and the second is via

some form of handhold on the bike below or aft of the co-rider’s seat.

When the pillion seat was separated from the rider’s seat, and when both those seats were far more saddle-shaped than is the case today, the seat-mounted grab handle worked fairly well. The co-rider could hold onto a strap attached at the front of her own saddle with relative ease, and with considerable distance between her knuckles and the rider's back. The advent of the so-called “dualseat'’ changed all that, although to meet governmental standards or perceived marketing needs, most manufacturers continued to bolt a strap to the seat.

If you rode during the Fifties, Sixties or early Seventies, you remember what that meant. First, it meant that in addition to sitting on an uncomfortably contoured dualseat, you inevitably wound up with your tailbone perched on, rather than ahead of, the cursed strap. Aside from throwing away the shocks and tires on most Japanese bikes of that era came with, the most common immediate modification was the instant elimination of the strap. Most people thought of them as a nuisance—and that they were ugly, to boot.

They were both, but they were also the only means the manufacturer usually had of ensuring that the corider had something to hang on to. As the factories got the word, and as the old-fashioned chromed-fender/miniseat look finally went away, to be replaced with the tailcone look, they redesigned their bikes with a grab rail around the back of the seat in place of the strap. Stylistically, it was a lot better, and allowed the co-rider more firmly to seat her weight into the

chassis, since the rail was (usually, but not always) fairly substantial.

Motorcycle fashion being eternally whimsical, the rail has become an endangered species. Now we have solutions like the early BMW K-bike seat, which incorporated sunken grabhandles on both sides of the seat. That proved unsatisfactory—the corider couldn’t really get a good grip on the handle inserts—and now all KModels have flying-buttress grab handles, sticking well out into the wind. This solution first saw daylight on BMW’s R65 L/S, and continues to be among the best yet devised for helping Debbie do her part.

But it’s still not good enough. Because, as you’ll know if you’ve tried the position for long, using those handles requires the co-rider to lean backward rather than forward, and the angle of the handles themselves can be tiring. Turn-key touring bikes like the Gold Wing Aspencade and Suzuki Cavalcade attempt to solve the problem by surrounding the corider with a car-style bucket seat; and while this actually does work rather well for those bikes, it clearly is not the answer for anything grossing less than half a ton.

If motorcycles were not so dreadfully altered, dynamically, by the addition of a passenger, none of this might matter. But paradoxically, it is the bikes most affected—the sportbikes—which need the help most and have the least-effective systems.

In all likelihood, however, we probably won’t see much progress in this mini-arena, especially since motorcycling is not geared to allowing a non-voting group (e.g., co-riders) much say in the matter of how the bucks are spent to buy the toys. So coriders will continue to hold onto belts and straps and whatever else they can, maybe squeezing their eyes shut and just hoping for the best, continuing to display courage of the highest order and never receiving any recognition for it other than the occasional grudging admission by the guy twisting the throttle that this time, Debbie didn’t slow him down too much.

Spencer’s got guts, sure. But what if he or any other racer had to ride behind somebody like himself? Or like you?

Here’s to you, Debbie.

Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue