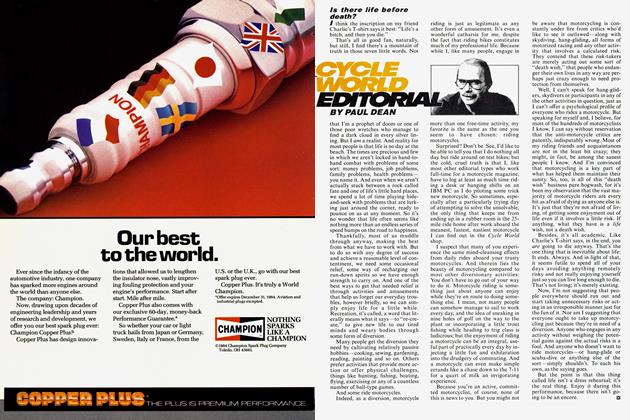

Pride and prejudice

EDITORIAL

I WAS SUPPOSED TO BE COMPLETELY unbiased. It says so right here in my trusty reporter's handbook, under the general heading of "objectivity." The journalist's pledge, the book tells me, is to be free of all prejudice and favoritism in reporting, to be eminently fair at all times.

I truly believe in that principle, and try to live up to it every minute I’m on the job. But on the last weekend of this past April, objectivity eluded my grasp, no matter how diligently I pursued it. I spent that Saturday and Sunday at the Uniroyal Proving Grounds just outside of Laredo, Texas, watching helplessly as, one by one, all of the world speed records this magazine set last September were blown sky-high by a VFR750 Honda.' Witnessing the demise of those records was tough enough; to be unbiased about it was asking too much.

I knew all along, of course, that our records wouldn’t last forever; by design, records are temporary structures, stationary targets erected to give challengers something specific to aim for. But I had hoped that our marks would survive at least long enough for the ink to dry on our FIM world-record certificates.

It didn’t work out that way. Our success on the Suzukis prompted Honda to challenge our records almost immediately. As Honda’s Jon Row, manager of the Communications Department that was a driving force behind the record attempt, told me after the event, “What you people at Cycle World did said some mighty impressive things about your abilities as a magazine staff, but as far as the public was concerned, your records also implied that the GSX-R750 was the best high-performance bike on the market. We wanted to prove that the VFR750 is better.”

Fair enough. But as far as I’m concerned, Honda did not prove that the VFR750 is a better motorcycle than the GSX-R750; what it did prove was that the VFR is a faster motorcycle than the GSX-R, faster by a whopping 15 mph in a 24-hour period. And aside from the fact that a bonestock VFR is about 5 or 6 mph faster in top speed than a bone-stock GSXR, there is one fundamental reason why the new records are so much higher: Honda’s objective at Laredo

was distinctly different than ours.

With our record attempt, we simply wanted to demonstrate, in a most graphic fashion, an elegant point about today’s streetbikes: that they possess an unprecedented combination of blistering speed and extraordinary durability. We chose the GSXR750 Suzuki because it was the leading-edge performance bike at the time, not because we had any vested interest in its success. Whatever speed it posted was fine with us, so long as it broke the existing record.

Honda’s goal, on the other hand, was to ensure that one of its important new products not only surpassed our marks, but raised those records to such high levels that no one would even attempt to break them fora long, long time. So Honda took the steps necessary to squeeze every last fraction of a mile-per-hour out of a stockengined VFR, including making minor changes to the aerodynamics and the gearing. In our effort, though, the GSX-Rs were left box-stock and completely street-legal.

What’s more, Honda spent a small fortune, using four times as many people, almost twice as many riders and tons more support equipment than we had used. Team Honda’s professional racing personnel treated pit stops as though the record run were a GP roadrace; we had just two permanent pit people (one a publisher and the other an associate art director) who enlisted the aid of offduty riders (all of whom were part of the Cycle World staff) to conduct pit stops that were leisurely by comparison. And whereas Honda conducted six full days of testing prior to its

record attempt, we showed up at the track barely a day ahead of time, allowed each rider a few orientation laps on a practice bike, and simply began our attempt the following day on bikes that most of us hadn’t even seen until arriving in Laredo.

What’s more, Honda was able to take advantage of our world-record experience by requesting—and getting—our advice while preparing for the attempt. We were asked to ride, as well, but declined; we saw no point in helping someone take away our records. Fair is fair, but that’s stretching the point. What’s more, if a major incident (such as the engine failure that occurred with journalist Rick Mitchell aboard) were to have happened while one of us was riding, some people might have forever suspected that we had somehow caused the problem in an effort to protect our records. We wanted to avoid that. But more than anything else, we didn’t ride because doing so would have made us, in effect, Honda employees playing a pivotal role in a major Honda promotional effort. That’s bad journalism of no small consequence. I must confess that I did ride in Kawasaki's record attempt in 1977; but I was wrong to have done so, and was just too naive at the time to know it. This time, I knew better.

Ifany or all of this sounds like sour grapes on my part, I don’t mean it that way. I was saddened by what the Honda people did, but highly impressed with their effort. If anything, perhaps I was a bit jealous. Because I’ll tell you this: If, when we made our record attempt, we would have had all of the resources at our disposal that Honda did, we wouldn’t have left any of them at home. Every person, every vehicle, every piece of equipment, every available dollar would have ended up in Laredo.

Besides, I consider the size and scope of Honda’s attempt a genuine compliment. If it took an effort that massive and organized to better our records, then what we had done truly must have been the monumental achievement we thought it was.

If you don’t agree, if you think I’m being a bit self-serving, you may be right. Like I said, when reporting what happened at Laredo, I can’t be very objective at all. Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue