Alas, in Safetyland

AT LARGE

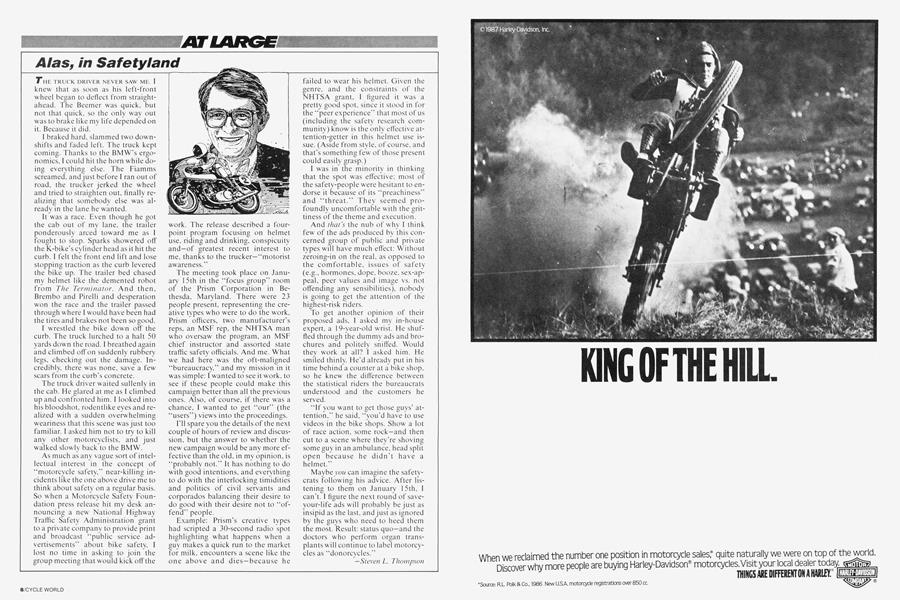

THE TRUCK DRIVER NEVER SAW ME. I knew that as soon as his left-front wheel began to deflect from straight-ahead. The Beemer was quick, but not that quick, so the only way out was to brake like my life depended on it. Because it did.

I braked hard, slammed two downshifts and faded left. The truck kept coming. Thanks to the BMW's ergonomics, I could hit the horn while doing everything else. The Fiamms screamed, and just before I ran out of road, the trucker jerked the wheel and tried to straighten out. finally realizing that somebody else was already in the lane he wanted.

it was a race. Even though he got the cab out of my lane, the trailer ponderously arced toward me as I fought to stop. Sparks showered off the K-bike's cylinder head as it hit the curb. I felt the front end lift and lose stopping traction as the curb levered the bike up. The trailer bed chased my helmet like the demented robot from The Terminator. And then, Brembo and Pirelli and desperation won the race and the trailer passed through where I would have been had the tires and brakes not been so good.

I wrestled the bike down off the curb. The truck lurched to a halt 50 yards down the road. I breathed again and climbed off on suddenly rubbery legs, checking out the damage. Incredibly, there was none, save a few scars from the curb’s concrete.

The truck driver waited sullenly in the cab. He glared at me as I climbed up and confronted him. I looked into his bloodshot, rodentlike eyes and realized with a sudden overwhelming weariness that this scene was just too familiar. I asked him not to try to kill any other motorcyclists, and just walked slowly back to the BMW.

As much as any vague sort of intellectual interest in the concept of “motorcycle safety,” near-killing incidents like the one above drive me to think about safety on a regular basis. So when a Motorcycle Safety Foundation press release hit my desk announcing a new National Highway Traffic Safety Administration grant to a private company to provide print and broadcast “public service advertisements” about bike safety, I lost no time in asking to join the group meeting that would kick off the

work. The release described a fourpoint program focusing on helmet use, riding and drinking, conspicuity and—of greatest recent interest to me, thanks to the trucker—“motorist awareness.”

The meeting took place on January 15th in the “focus group” room of the Prism Corporation in Bethesda, Maryland. There were 23 people present, representing the creative types who were to do the work, Prism officers, two manufacturer’s reps, an MSF rep, the NHTSA man who oversaw the program, an MSF chief instructor and assorted state traffic safety officials. And me. What we had here was the oft-maligned “bureaucracy,” and my mission in it was simple: I wanted to see it work, to see if these people could make this campaign better than all the previous ones. Also, of course, if there was a chance, I wanted to get “our” (the “users”) views into the proceedings.

I’ll spare you the details of the next couple of hours of review and discussion, but the answer to whether the new campaign would be any more effective than the old, in my opinion, is “probably not.” It has nothing to do with good intentions, and everything to do with the interlocking timidities and politics of civil servants and corporados balancing their desire to do good with their desire not to “offend” people.

Example: Prism’s creative types had scripted a 30-second radio spot highlighting what happens when a guy makes a quick run to the market for milk, encounters a scene like the one above and dies —because he failed to wear his helmet. Given the genre, and the constraints of the NHTSA grant, I figured it was a pretty good spot, since it stood in for the “peer experience” that most of us (including the safety research community) know is the only effective attention-getter in this helmet use issue. (Aside from style, of course, and that’s something few of those present could easily grasp.)

I was in the minority in thinking that the spot was effective; most of the safety-people were hesitant to endorse it because of its “preachiness” and “threat.” They seemed profoundly uncomfortable with the grittiness of the theme and execution.

And that's the nub of why I think few of the ads produced by this concerned group of public and private types will have much effect: Without zeroing-in on the real, as opposed to the comfortable, issues of safety (e.g., hormones, dope, booze, sex-appeal, peer values and image vs. not offending any sensibilities), nobody is going to get the attention of the highest-risk riders.

To get another opinion of their proposed ads, I asked my in-house expert, a 19-year-old wrist. He shuffled through the dummy ads and brochures and politely sniffed. Would they work at all? I asked him. He smiled thinly. He’d already put in his time behind a counter at a bike shop, so he knew the difference between the statistical riders the bureaucrats understood and the customers he served.

“If you want to get those guys’ attention.” he said, “you'd have to use videos in the bike shops. Show a lot of race action, some rock—and then cut to a scene where they’re shoving some guy in an ambulance, head split open because he didn't have a helmet.”

Maybe von can imagine the safetycrats following his advice. After listening to them on January 15th, I can't. I figure the next round of saveyour-life ads will probably be just as insipid as the last, and just as ignored by the guys who need to heed them the most. Result: status quo—and the doctors who perform organ transplants will continue to label motorcycles as “donorcycles.”

—Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialDouble Jeopardy

May 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupCapturing the Experience

May 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

May 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

May 1987 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

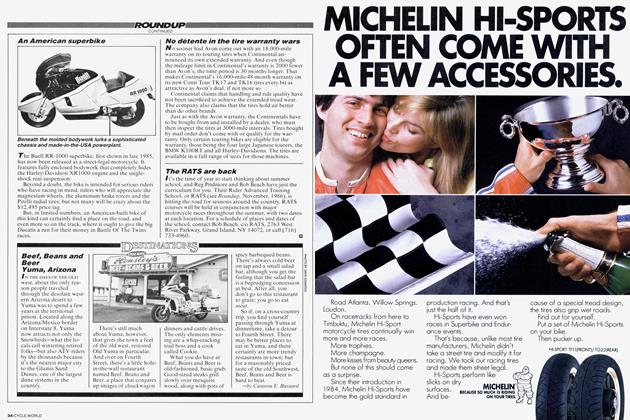

RoundupBeef, Beans And Beer Yuma, Arizona

May 1987 By Camron E. Bussard