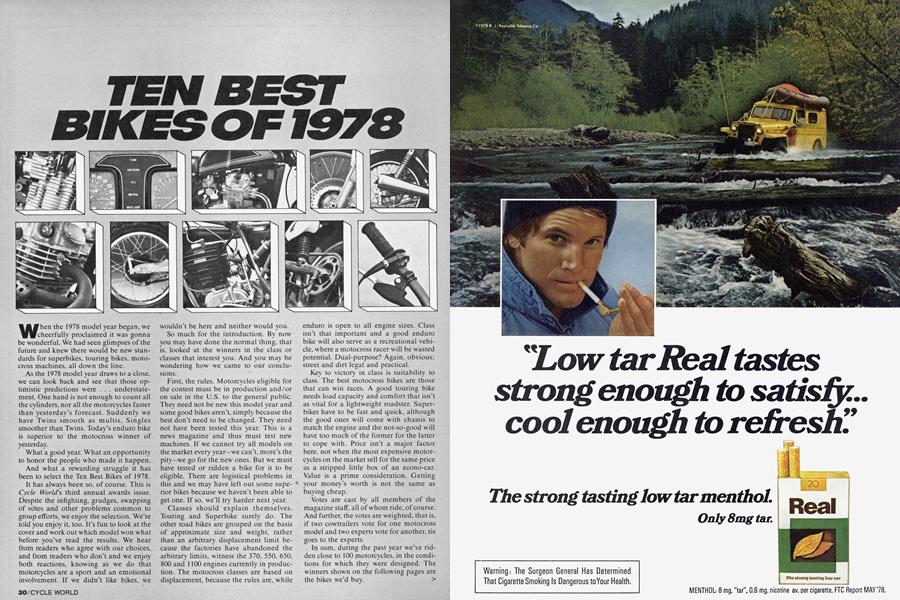

TEN BEST BIKES OF 1978

When the 1978 model year began, we cheerfully proclaimed it was gonna be wonderful. We had seen glimpses of the future and knew there would be new standards for superbikes, touring bikes, motocross machines, all down the line.

As the 1978 model year draws to a close, we can look back and see that those optimistic predictions were . . . understatement. One hand is not enough to count all the cylinders, nor all the motorcycles faster than yesterday’s forecast. Suddenly we have Twins smooth as multis, Singles smoother than Twins. Today’s enduro bike is superior to the motocross winner of yesterday.

What a good year. What an opportunity to honor the people who made it happen.

And what a rewarding struggle it has been to select the Ten Best Bikes of 1978.

It has always been so, of course. This is Cycle Worlds third annual awards issue. Despite the infighting, grudges, swapping of votes and other problems common to group efforts, we enjoy the selection. We’re told you enjoy it, too. It’s fun to look at the cover and work out which model won what before you’ve read the results. We hear from readers who agree with our choices, and from readers who don’t and we enjoy both reactions, knowing as we do that motorcycles are a sport and an emotional involvement. If we didn’t like bikes, we wouldn’t be here and neither would you.

So much for the introduction. By now you may have done the normal thing, that is, looked at the winners in the class or classes that interest you. And you may be wondering how we came to our conclusions.

First, the rules. Motorcycles eligible for the contest must be in production and/or on sale in the U.S. to the general public. They need not be new this model year and some good bikes aren’t, simply because the best don’t need to be changed. They need not have been tested this year. This is a news magazine and thus must test new machines. If we cannot try all models on the market every year—we can’t, more’s the pity—we go for the new ones. But we must have tested or ridden a bike for it to be eligible. There are logistical problems in this and we may have left out some superior bikes because we haven’t been able to get one. If so, we’ll try harder next year.

Classes should explain themselves. Touring and Superbike surely do. The other road bikes are grouped on the basis of approximate size and weight, rather than an arbitrary displacement limit because the factories have abandoned the arbitrary limits, witness the 370, 550, 650, 800 and 1100 engines currently in production. The motocross classes are based on displacement, because the rules are, while enduro is open to all engine sizes. Class isn’t that important and a good enduro bike will also serve as a recreational vehicle, where a motocross racer will be wasted potential. Dual-purpose? Again, obvious; street and dirt legal and practical.

Key to victory in class is suitability to class. The best motocross bikes are those that can win races. A good touring bike needs load capacity and comfort that isn’t as vital for a lightweight roadster. Superbikes have to be fast and quick, although the good ones will come with chassis to match the engine and the not-so-good will have too much of the former for the latter to cope with. Price isn’t a major factor here, not when the most expensive motorcycles on the market sell for the same price as a stripped little box of an econo-car. Value is a prime consideration. Getting your money’s worth is not the same as buying cheap.

Votes are cast by all members of the magazine staff, all of whom ride, of course. And further, the votes are weighted, that is, if two cowtrailers vote for one motocross model and two experts vote for another, tie goes to the experts.

In sum, during the past year we’ve ridden close to 100 motorcycles, in the conditions for which they were designed. The winners shown on the following pages are the bikes we’d buy. >

SUPERBIKE: SUZUKIGS1000

Speed and power are what Superbikes are all about. Except that when that definition began, there were few production bikes with more speed than normal and what they also had in common was handling that bordered on the, uh, demanding. Fast bikes were rare and because the fast bikes were demanding to the point of foolishness, their handling or lack of it was part of the package.

Not any more. This year we’ve seen four stock motorcycles capable of running the standing quarter mile in less than 12 seconds. A couple others are right down close to it, so we can take speed for granted. Those of us who like the drags can come out of our choice of showroom ready for a trophy.

Balance has become the important part. The factories have proved you can make a fast bike that’s quiet and priced within reason and reliable.

Suzuki has proved you can have a quick bike that’s also a sports bike, a road bike with control. More than muscle, as we said during the test.

The GSJ000 engine is good, but it's not the best, not in power output or number of cylinders or in innovation.

The GSIOOO chassis and suspension make it the winner. The frame is strong and stiff in the right places. The suspension has been beefed to match the engine and tuned to match the rider's will. Better, the rider can tune to suit himself. Along with rear spring pre-load, you can adjust rear damping. The forks have air caps, as in motocross, and front end stiffness can be dialed in or out, as ordered.

The GS 1000 is the lightest in class. Tflhas the best handling and with its power and clean understated good looks, the GSIOOO has to be the Superbike of the Year.

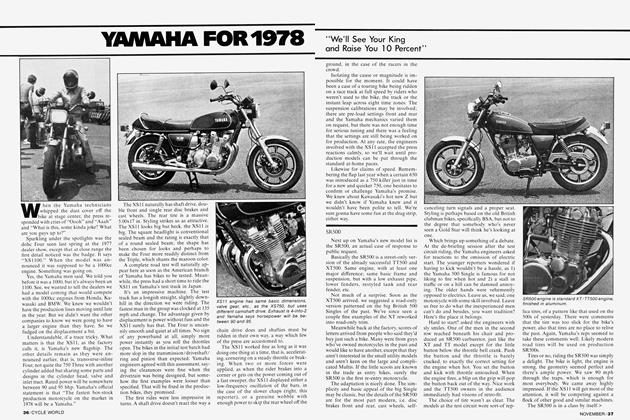

TOURING: YAMAHAXS11

Yamaha had something of a surprise for the 1978 model year. The lOOOcc Four shown but not sold during 1977 turned out to have been a gambit, something to lull the opposition. When Yamaha’s real big new bike appeared, it was an 1100, what the rival factories offered plus 10 per cent.

The whopping great engine and shaft drive and various other bits designed to be beefy enough for the powder train made the XS11 the heaviest of the new' Superbikes, so the engine’s size was countered by the bike’s size at the dragstrip.

What the beef also does is make the XS11 into a fine touring bike. The best of the year and perhaps the standard against which the other entries in the touring market are now judged.

What does a touring bike need? Not just power and surely not just speed. The prime demand is for smooth torque, the kind that takes the machine, the people, the touring package and the gear up those long grades in top gear. The XS11 will do it without buzzing, downshifting or strain.

Suspension is fine for solo and is still firm enough to handle the chuckholes when fully loaded. The seat never intrudes. The bars and controls work well as delivered and when the bike is fitted with fairing and bags. The factory has gone to great lengths to make sure the buyer can find good add-on equipment, tailored to the bike and priced within reason. You can’t ask for more than that.

HEAVYWEIGHT ROADSTER: BMWR80

Now that the burden of being toughest two-wheeler in town has fallen to the new breed of one-liter cannons, the 750 class can do other things, more specifically

the things that count for those of us who can see beyond a quarter mile.

Enter the R80. It’s a new BMW in the old manner, with more displacement gained by enlarging the bore and with power delivered at mid range, just right for the road. The R80 will not win class at the drags. It isn’t the best around a pool-table turn on the pegs. And it has normal BMW quirks, as in shaking at idle, reaction to engine torque, the legendary clunk and a few others.

Never mind. Because a 750 doesn’t have to be quick—you want more speed, buy a bigger engine—and because road riding is more apt to be coping with surprise chuckholes and sudden showers than shaving lap times in the turns, why, the R80 becomes a superior sports bike.

Versatile. We did a comparison test of 750s. one of which was an 800, an Irishism Henry' tells us, and learned that for sports touring, no fairing and no saddlebags but w ith overnight stuff and rain gear lashed to the bike fore and aft, racing isn’t the answer.

What the answer was, was sitting there fat and sassy while that lovely soft suspension ate the bad road, and splashing through the water that didn't upset the tires, and knowing that the brakes don’t care if it rains or freezes. Having the R80 win the top-gear pulls every time didn't hurt either.

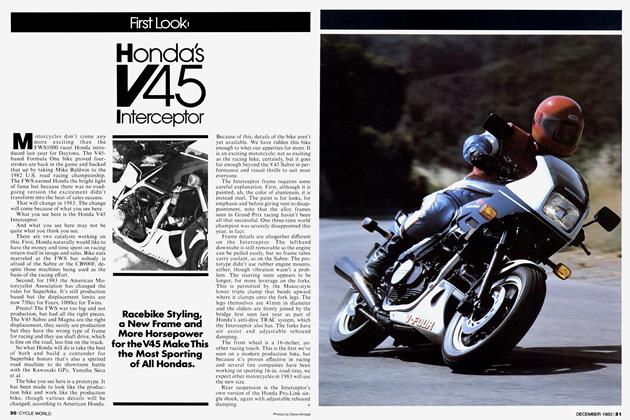

MIDDLEWEIGHT ROADSTER:HONDACX500

Today’s engineering tour-de-force will likely be the tomorrow’s majority. The CX500 is the most advanced and most different model of 1978.

You could spend the day just looking. The stressed-engine frame, the V-Twin with engine block, the counter-rotating clutch and drivetrain cancelling out the engine’s torque reaction, the 10,000-rpm with pushrods, the skewed cylinder heads, over and over the CX500 gives answers where the other factories can only repeat the questions.

Riding the CX500 is better still. It's big and heavy and by all the rules it shouldn’t be sporting . . . but it is. The supple handling and highly tuned engine should reduce comfort. . . but they don’t.

The CX500 breaks most of the rules. Enthusiasts are supposed to be buying larger motorcycles, and most of the leading models for 1978 were styled, that is, they are supposed to look like the customized bikes of yesterday. So Honda puts its engineers to w'ork on a middleweight, with only two cylinders, and the styling department furnishes a couple of touches right of the foolish 50s, plus an engine that looks like an air compressor.

Such is the superiority of the design, though, and so convincing are the specifications to those who take the trouble to look, that the CX500 is selling well and we have yet to meet a CX500 owner who didn’t still fall in love every Sunday morning-_ :

LIGHTWEIGHT ROADSTER: HONDAHAWK 400TI

Future shock may have blurred our first impressions of Honda’s 400 Twins. The Hawks revived a treasured name, while being entries in a not-too-exciting class and perhaps because the Hawks were the first of the new look from Honda, our reactions were mildly in favor: The new models had some clever touches, and some unusual features, but two cylinders and only two cylinders and besides, the bikes look, well, lumpy.

The Hawks have been with us for a year now, and we’ve come to appreciate them for what they are. The open-frame-withstressed-engine works. The elaborate counterbalancing does smooth the engine. Still not a Four but a heap better than the average Twin.

Our special favorite, though, is the Hawk Tl. Right, the bargain version, with wire wheels and drum brakes. We like it because on the one hand, the Tl is a good buy. It has everything it needs, and the price is fair and the drivetrain is properly executed, all of which ensures that if the new rider has any aptitude for two wheels at all, he or she will be happy and may. our nature being what it is, move up to larger engines and larger trips.

Plus, the TI is the lightest and the

quickest and the fastest.

The Tl wins box stock class at the road races. Amazing but true. It has the power and the handling to beat all the rival 400s. Yes, that one too.

Good time for the novice, victory circle for the sportsman, and the Hawk 400 Tl has the rest of its world surrounded.

DUAL PURPOSE: HONDAXL250S

For dual-purpose riders there was no better news for 1978 than Honda’s new XL250.

A design coup, the new XL had only engine class and designation in common with the original four-stroke Single of 1972, which was a good bike then and woefully outmoded by the time production stopped in 1977.

Honda was ready. The XLS is one of four stunning new models (mind, the CBX is officially a 1979) for Honda for 1978. Like the CR, the CX500 and the Hawks, the XL uses an open frame with stressed engine, the better for lightness with rigidity. The XL engine has dual secondary balancers so rider and frame don’t get buzzed beyond their limits. Precise planning and execution allowed Honda to build the new Single lighter, stronger and more powerful than the old unit, and the result is smoother than several Twins.

The list could go on and on, with the 23in. front wheel, Honda’s own trials tire design, the extraordinarily long shocks, the small transmission gained by reducing torque multiplication at the primary drive, etc.

Point is, a dual-purpose bike is supposed to be usable on road or through ruts. Some bikes have been good at one and bad at the other.

We took the XLS and its three leading rivals on a camping trip. No surprise. The XL was clearly the best on the highway, and the best in town, it was also the fastest across open country and through the woods.

Socko. The dual-purpose bike has fallen into some disfavor, as land closures and the clear dirt superiority of pure dirt bikes

have forced license plates back onto the road, so to speak.

But the time may be coming when fueling the truck is more than the pocket can take and when government controls make it impossible to ride a pure dirt bike on public lands.

When that day comes, the dual-purpose bike will once again be a prime market.

Honda is ready when we are.

125 MOTOCROSS: SUZUKIRM125C

Surprising, in a way. The 125 class used to be the hottest thing in the showroom, sort of a winner-of-the-week club.

This year several of the factories had other things on their drawing boards. Honda dazzled us with the CR250, but the expected CRI25 didn’t arrive. Kawasaki sprang its semi-works KX 125 and a good one it is, but production was limited, indeed the factory intended for the bike not to be sold to the general public, so dealers could sponsor teams and attract the sporting eye. Yamaha did some updating, but nothing major.

Suzuki, though, never let up. The ’77 version, the 125B, was a potential winner. So Suzuki refined it into the 125C, with an aluminum swing arm, rear shocks with remote reservoirs and adjustable damping, a six-speed transmission and a full-floating rear brake.

The RM125C is a serious racing bike. It’s long, with a wheelbase equal to those seen in open class motorcross not many years ago. It's light, at less than 200 lb. on the line. Power is equal to anything in the class, and although the racer does need to shift the engine always within the powerband, the 125’s new pipe and porting gives power at the low end as well.

Few tricks here. Enthusiasm for 125 motocross is as high as ever, and the racing is as fierce. With the 1978 RM, Suzuki has continued its progress while the others were too late or not ready.

250 MOTOCROSS: HONDACR250R

Such a comeback. First time Honda went the two-stroke route the Elsinore ruled. Then it sat still and everybody in the business threw dirt on the poor Elsie on their way to longer travel, better steering and more power.

Honda rebuilt its racing team and produced new motocross bikes for the team. Now we’ve seen the logical step, as the RC250 becomes the CR250R, a for-sale version of the team machines.

The CR250 is pretty close to the RC. Same frame design and suspension, allowing for several materials changes and for team-member preference. Front and rear wheel travel is nearly one full foot. The engine has as much power as any 250. It’s tuned for the top end, as a racing engine should be, but heavy flywheels keep the motor pulling down low as well. The CR250 is light, the seat isn’t as high as the wheel travel would lead one to predict, and the bike turns and slides as if it was much lower than it is.

The winner here is the result of another comparison test, with riders from pro to novice turning laps on four 250 motocrossers.

To a man the testers preferred the Honda. It lost an occasional race, and didn’t win all the tests. But it did everything well, on a variety of tracks, which makes it the pick for the privateer.

Racing is racing and winning is the only thing. The model year has been a good one and the racer has a choice of good 250s. But because none of them are markedly different from the CR250 in any important way. we have a flock of close second-places and no sentimental picks. >

OPEN MOTOCROSS:MAICO 450

Although open class motocrossers compete for world and national titles, competition in the real world, local track and local racers, tends to put the rising young stars on the 125 and 250 machines and the established older/sportsmen guys on the open bikes, 370 to 500 or so. Because the privateer is the main man here, the best mount has to be that which gives something extra to the privateer.

Which the Maico does. It's a small firm, in fact a family company and family operation, so Maico tends to do things in the Maico way. That means no copying. The list of things Maico did first is a long one. Unlike some other independents, Maico is willing to change.

The 1978 Maico Magnum 450 is changed. The frame is new, strong like always and with that elusive balance Maico does best in the world, despite the outsiders trying to copy it. Steering is normal Maico, which is to say so good that when experienced riders make comparisons, they say a bike steers almost as well as a Maico. Engine cases are tiny and the rear sprocket has been moved back almost to the swing arm pivot, to keep chain tension change to a minimum. The exhaust, an up pipe at last, brings power on early and keeps it coming.

So. The Maico 450 is designed to work on all tracks. It turns and jumps and has not only all the power an open rider can use, but power all the time: Get the holeshot and the other guys have to get around you. It's beautifully made and nice to look at. Worth the money, in sum, and a fine bike for the serious hobbyist.

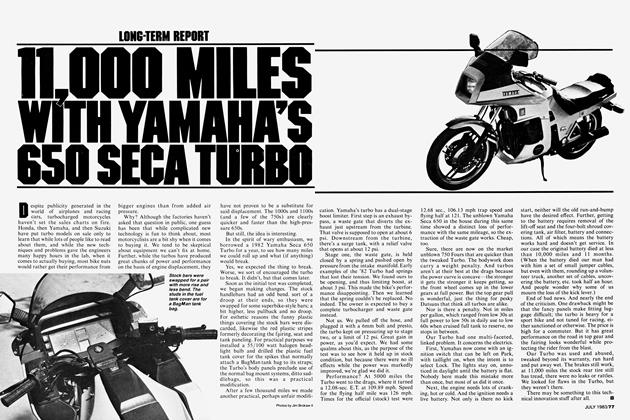

ENDURO: SUZUKI PE175

A good enduro bike has to be lots of .things to lots of different riders. There are competition guys who ride very hard and need what amounts to a motocross machine with traces of road equipment. There are serious riders who don’t actually compete, and there are bike nuts who plain enjoy riding around in the woods and desert.

Satisfying all these people is difficult. What it takes is racing suspension that’s soft, a powerful engine without temperament, stability at speed with agility in the twisties, and light weight wfith plenty of strength. Low price helps. So does reliability.

That's a demanding set of specifications. Suzuki’s PE 175 comes closest.

The first PE, the 250. gave Suzuki a clear lead on the field, in that the PE w’as the first mass-produced enduro bike that was a true challenge to the limited production European bikes.

The PE 175 has (naturally) a smaller engine. It also benefits from a year in the field, as Suzuki was able to fine tune the chassis for the demands of U.S. play and competitive riders.

At the high end of the scale, AA riders can make minor changes to the PE 175 and\ win class, as they already have.

The same bike is as steady and reliable as the old foo-foo models were; children or novice friends or waves or whoever can straddle the PE 175 and ride without fear. The PE 175 will slog through mud, idle up hills, clamber across rocks, at whatever pace the rider sets.

The engine size of course makes the 175 not quite enough for a big man. say 170 lb. or more. Everybody else, of all talents, will do fine. For the price, or for a w hole bunch more, you can't beat the PE 175.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontYou Can't Take the Harley Out of the Boy

October 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Departments

DepartmentsBook News

October 1978 By A.G., Chuck Johnston, Michael M. Griffin -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1978 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

October 1978 -

Short Strokes

October 1978 By Tim Barela -

Technical

TechnicalYamaha It250/400 Steering Fix

October 1978 By Len Vucci