Motorcycle Emissions

Miles Brubacher

California has done it again! The state became the first government entity to adopt exhaust emission standards for motorcycles, applicable to bikes manufactured after January 1, 1978. You may remember that California was the first to apply exhaust emission standards to cars in 1966. This is not surprising, of course, because California, and especially the Los Angeles Basin, has the worst vehicle air pollution problem in the world. It is called photochemical smog. The dirty, brown stuff is formed from a reaction of hydrocarbons and nitrogen oxides in sunlight. Hydrocarbons are unburned gasoline and nitrogen oxides are formed from any combustion process. The amount of photochemical smog in the air is measured by the oxidant reading. Los Angeles reaches oxidant levels three times as high as those of other large cities. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has concluded that the only states other than California that may have a significant air pollution problem from motorcycles are Arizona and New Jersey. Arizona has only onefifth the number of motorcycles that are in the Los Angeles Basin, and New Jersey has only one-fourth as many. So, it is difficult to believe that there is a real air pollution problem from motorcyles in any state other than California.

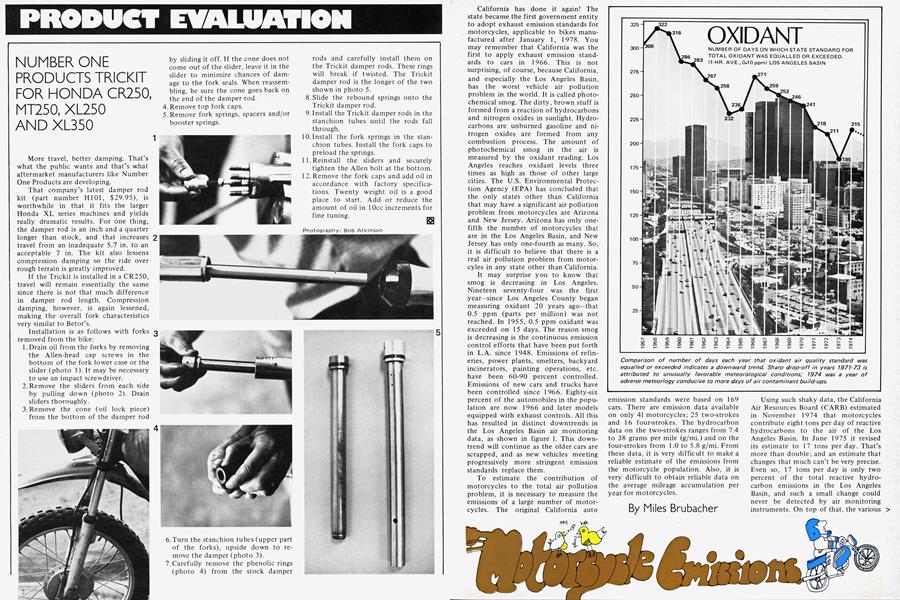

It may surprise you to know that smog is decreasing in Los Angeles. Nineteen seventy-four was the first year—since Los Angeles County began measuring oxidant 20 years ago—that 0.5 ppm (parts per million) was not reached. In 1955, 0.5 ppm oxidant was exceeded on 15 days. The reason smog is decreasing is the continuous emission control efforts that have been put forth in L.A. since 1948. Emissions of refineries, power plants, smelters, backyard incinerators, painting operations, etc. have been 60-90 percent controlled. Emissions of new cars and trucks have been controlled since 1966. Eighty-six percent of the automobiles in the population are now 1966 and later models equipped with exhaust controls. All this has resulted in distinct downtrends in the Los Angeles Basin air monitoring data, as shown in figure 1. This downtrend will continue as the older cars are scrapped, and as new vehicles meeting progressively more stringent emission standards replace them.

To estimate the contribution of motorcycles to the total air pollution problem, it is necessary to measure the emissions of a large number of motorcycles. The original California auto emission standards were based on 169 cars. There are emission data available on only 41 motorcycles; 25 two-strokes and 16 four-strokes. The hydrocarbon data on the two-strokes ranges from 7.4 to 38 grams per mile (g/mi.) and on the four-strokes from 1.0 to 5.8 g/mi. From these data, it is very difficult to make a reliable estimate of the emissions from the motorcycle population. Also, it is very difficult to obtain reliable data on the average mileage accumulation per year for motorcycles.

Using such shaky data, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) estimated in November 1974 that motorcycles contribute eight tons per day of reactive hydrocarbons to the air of the Los Angeles Basin. In June 1975 it revised its estimate to 17 tons per day. That’s more than double; and an estimate that changes that much can’t be very precise. Even so, 17 tons per day is only two percent of the total reactive hydrocarbon emissions in the Los Angeles Basin, and such a small change could never be detected by air monitoring instruments. On top of that, the various > government air pollution control authorities can’t even agree on all the hydrocarbons that are reactive and contribute to photochemical smog. The Los Angeles County Air Pollution Control District’s opinion differs from CARB’s, which differs from EPA’s. It is a confusing subject, and it would not seem wise to base a motorcycle emission control program costing many millions of dollars on such controversial data.

While most of the air pollution problem in Los Angeles comes from automobiles, this is not true in the other U.S. metropolitan areas. On the basis of toxicity, or harmfulness to people, at least three-quarters of the air pollution in the U.S. comes from stationary sources, such as steel mills, power plants, refineries, other industrial and domestic furnaces, burning dumps, etc. With little regard for this fact, Congress passed the “Muskie” law in 1970 which set standards so strict for 1975 automobiles that the only way most manufacturers could meet the standards was by using catalytic converters. These devices do a good job of controlling hydrocarbon emissions if everything is working properly. Catalysts have been used for many years in oil refineries and chemical processes, where conditions of temperature, flow rate and flow composition are held constant. However, on a car, none of these things are constant. Indeed, with ignition or carburetion malfunctions, the temperature of a catalyst may reach white heat and melt.

Presently, there is much controversy about the catalysts on 1975 cars. There is concern that there may be a fire hazard from the high temperatures of a catalyst with engine malfunctions. There is concern about sulfuric acid emissions from catalyst cars. A motorcycle presents even more extreme problems for a catalyst than does a car, so it is improbable that catalysts can be used on motorcycles. One of the reasons people buy motorcyles is that they are simple machines. Catalysts might add such cost, weight and complication to motorcycles that many people would be discouraged from purchasing them.

Four-stroke motorcycles are low emitters of air pollution compared to cars. An uncontrolled four-stroke motorcycle emits about one-third as much hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide as an uncontrolled car, or about the same amount as a 1974 model car. Nitrogen oxide emission from a motorcycle is about one-twentieth that of a car. Two-stroke motorcyles are bad actors from the standpoint of hydrocarbon emissions. A two-stroke motorcycle emits 18 times the hydrocarbons of a 1975 model California car and 40 times the hydrocarbon emissions of a car meeting the 1977 California standards.

The motorcycle exhaust emission standards that were adopted by the CARB are shown in figure 2, together with car standards and average emissions of uncontrolled cars and motorcycles. Standards for hydrocarbon emissions only were adopted, because emissions of other pollutants from motorcycles are essentially negligible.

In considering motorcycle emission standards and the future role of the motorcycle in society, there is a fact that is very important. That fact is that a motorcycle provides personal transportation while using only one-fourth to one-third the energy of an automobile. It doesn’t do any good to argue that a car can carry more people, because the average occupancy of automobiles in urban traffic is 1.2 persons. If we predict the future from the Los Angeles air pollution trend we have seen, it is plain that vehicle air pollution is being removed as a major problem of society.

On the other hand, the energy problem is going to be with us for decades into the future, and it’s going to get worse before it gets better. The age of cheap energy is over, and as the price of gasoline rises toward $1 per gallon, small cars and motorcycles will attract, and will serve a real need for, more and more people in America.

In the winter of 1974, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed a motorcycle emission standard of 8 g/mi. hydrocarbons. Since that time the Motorcycle Industry Council (MIC) has been working with EPA to obtain more baseline emission data on motorcycles and to more closely examine the technical and economic feasibility of controlling emissions from motorcycles. If the standards force all two-strokes immediately off the American market, people may just decide not to buy motorcycles and rebuild their old ones. This has happened to some extent in the automobile market in 1975, and motorcycle purchases are much more a whim of fancy. If people stop buying new motorcycles and keep running their old ones, or buy old cars instead, the air will not become any cleaner.

Therefore, after more thorough evaluation of the situation, in the spring of 1975 EPA issued a second proposal for motorcycle emission standards. This was for a sliding hydrocarbon standard dependent upon engine size. Up to 169cc, 8 g/mi.; 750cc and over, 14 g/mi.; and in between a straight-line function according to the engine size. This means about a 40 percent reduction in hydrocarbon emissions for two-strokes; but four-stroke emissions are already far below this standard without any controls. Obviously, EPA did not want to wipe out the two-strokes, even the big ones, in 1978.

EPA wants to bring motorcycle emission standards in line with car emission standards by 1980. Just what car emission standards will be for 1980 is presently a matter of dispute between the President and Congress. The President wants emission standards held at the 1975 level until 1982 because of concern over sulfuric acid emissions of catalysts and the big effects of severe emission standards on increasing vehicle fuel consumption. Senator Muskie and some of his colleagues want to continue to “hold Detroit’s feet to the fire” with tough emission standards.

Motorcyclists are very fortunate to have an organization like the Motorcycle Industry Council that works effectively against unreasonable motorcycle regulations by the government. While the MIC represents motorcycle manufacturers rather than motorcycle riders, in this case the interests of the two groups are similar. MIC has been cooperating for the past two years with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency with the goal being EPA’s adoption of reasonable motorcycle emission standards. In fact, MIC recommended that EPA adopt emission standards, rather than discriminatory and unwise restrictions of motorcycle usage, in California in order to meet clean air standards.

At the recent public hearing held by CARB, MIC presented a very strong statement. It pointed out the many reasons why an overly stringent motorcycle emission standard would be unwise. MIC tallied up the economic costs of overly stringent standards that might result in a 60-percent loss in new motorcycle sales in California. They estimated that the direct loss in new motorcycle sales would be $128 million. Parts and accessories, advertising, financing charges and insurance would represent another $42 million lost. Also, the State of California would lose $17 million each year in taxes.

With California motorcycle sales reduced by 60 percent, 1900 people would be laid off from their jobs in the motorcycle industry. The potential state outlay in unemployment compensation for these 1900 people is $4.5 million. These figures do not include the secondary, ripple effects that 1900 job losses would cause. Naturally, these people would be less likely to buy other goods and services if they were deprived of their normal means of livelihood. This strong statement, bristling with facts and figures, helped persuade CARB not to adopt a 1.6-g/mi. motorcycle hydrocarbon emission standard for 1978, as initially proposed. MIC believes that the CARB action of adopting motorcycle emission standards was hasty and without sound technical foundations. Therefore, MIC may take CARB to court and/or introduce a bill in the California Legislature to void the motorcycle standards set by CARB.

(Continued on page 63)

Continued from page 50

In order to consider the effect the California motor emission standards may have on the motorcycle business, let’s take a look at the market. The United States and world motorcycle markets are dominated by the Japanese manufacturers. Honda, Yamaha, Kawasaki and Suzuki account for about 85 percent of U.S. sales. Harley-Davidson only sells 6 percent and NortonTriumph only 1.3 percent. BMW sells slightly less than 1 percent. Honda alone sold 42 percent of the motorcycles in the U.S. market in 1974. In recent years, Honda has marketed a few two-stroke models, but otherwise nearly all Hondas have four-stroke engines. About 15 percent of Honda’s California sales are of two-stroke off-road bikes. Conversely, Yamaha and Kawasaki recently have introduced four-stroke road bikes, which account for about 15 percent of their sales. Suzuki’s motorcycles are all two-strokes. Two-stroke motorcycles are mostly under 250cc, whereas fourstrokes are fairly evenly divided throughout the motorcycle size range. Honda is the only major manufacturer that makes four-stroke bikes under 170cc. In California, 24 percent of the motorcycles are off-road machines, and it is not proposed to regulate the emissions of these. Of the 300,000 streetlegal motorcycles in the Los Angeles Basin, 56 percent have four-stroke engines and the remaining 44 percent have two-stroke engines.

Figure 3 shows sales of the various makes of motorcycles last year in the U.S. and in California, and also the estimated additional cost that will be added to each bike for the certification costs of meeting emission standards. These -costs do not include the cost of engineering and tooling to produce engines to meet the standards.

What do the individual motorcycle manufacturers say about the California exhaust emission standards? Honda, the largest seller in the U.S. and California, makes nearly all four-strokes. Four-strokes are under the 8-g/mi. standard now, so it has no problem with the California standards until 1982. By that time, it can probably meet 1.6 g/mi. The second largest seller, Yamaha, currently markets 13 models of two-strokes and two four-stroke models. Yamaha has said that it will cost $7 million to convert all models to four-strokes, or a total of $81 million by 1982. The advantages it has stated for two-strokes are 20 percent fewer parts, 35 percent lighter weight, and higher torque.

Kawasaki sells 20 two-stroke models and three four-strokes. It says that motorcycles have no statistically significant effect on air pollution. Kawasaki is the first foreign motorcycle manufac-

turer to set up an assembly plant in the U.S. This new plant is in Lincoln, Nebraska. In California, it has 100 dealers and 1500 employees. Two-thirds of its annual $30 million sales in California are two-strokes. The dealers couldn’t survive selling Kawasaki four-strokes only. Kawasaki says it takes five years to engineer and tool for a new model, which would apply to conversion from two-stroke to four-stroke engines.

Suzuki says that it will introduce four-stroke motorcycles soon, but it will take $65 million and up to 10 years to convert its entire line from two-strokes. It says it can’t meet 16 g/mi. with two-strokes before 1981, and meeting stringent standards with two-strokes will slow the conversion of all its models to four-strokes. It says that fitting a catalyst or afterburner to a motorcycle adds so much in cost and complication that the motorcycle ceases to be an attractive method of mobility. Suzuki says people would not buy and use such motorcycles.

In summary, then, almost any motorcycle emission standard will force twostroke machines off the market for street use. The only question is time. If a stringent emission standard is imposed in two or three years, the manufacturers of two-stroke motorcycles and their dealers will be in big trouble. However, if a stringent motorcycle emission standard is postponed for five to seven years, then the manufacturers have a chance of converting to four-stroke engines. Even so, conversion will be very expensive, and many buyers may leave the motorcycle market.

(Continued on page 102)

Continued from page 63

Does all of this give you a helpless feeling that big government is taking over? Everyone wants clean air, but there are some real questions about the contribution of motorcycles to air pollution in California and even more on a national basis. If you don’t want twostroke motorcycles regulated off the street market, there are things you can do about it.

The first thing to do is join the American Motorcycle Association. It is not just for competition riders. You can be an “Enthusiast” member for only $8 per year. The AMA testifies on your behalf for more reasonable motorcycle laws and regulations. They testified before CARB in defense of two-stroke motorcycles. You know how effective the Sierra Club is in environmental legislation and litigation. The AMA and the Sierra Club both have the same number of members in the U.S., about 140,000. The difference is that Sierra Club members are activists. They write letters, and they testify before legislatures and other government commissions. They get involved.

You can get involved, too. There’s no magic required to speak or write effectively to legislators. In fact, people who speak or write in plain English sometimes have great impact on government hearings. These proceedings usually are filled with bureaucratic double talk. Here are some suggestions for letter writing: Find the names and addresses of your Congressmen and your state legislators from your local librarian. Borrow a typewriter since it is difficult to read handwriting. Be respectful, not abusive. Give some facts and figures. Humor helps get their attention. Suggest alternatives; you probably know about some factories, furnaces, or burning dumps in your neighborhood that need better air pollution control. Legislators respond to voters. After all, it’s you who keeps them in office. If a legislator gets a few dozen letters on a particular subject, he pays attention. It’s surprising what an impact you can have on the future of motorcycling.