BOY RACER

What's "old" anyway? That's the question when a veteran roadracer goes vintage racing and discovers he's still a "kid"

BRIAN CATTERSON

IT WAS A CLASSIC CASE OF youth and enthusiasm versus old age and treachery, except that for the first time in a long time, I was representing the younger side of the equation.

You see, I was minding my own business, out lapping Willow Springs Raceway aboard a 1962 AJS 7R while David Dewhurst snapped some photos, when all of a sudden, Jody Nicholasyes, that Jody Nicholas, former AMA fast guy and CW staffer from the 1970s-smoked past me on the front straightaway. Now, I may have gotten my ass handed to me by a $73,000 Dodge Viper not too long ago, but I'll be damned if I'm gonna get blown off by some geezer on a Beezer-or, to be accurate, a Manx Norton. So I wicked it up, rode around the outside of him in Turn 2 and proceeded to try to blow him off.

Nothin' doin'. Weird knees-on-the-

tank riding style and all, the codger hung tough. And while he never managed to repass me, I could hear him back there the whole time. Never mind that Nicholas hadn’t really raced since The Big Crash at Riverside in 1979, and hadn’t ridden at Willow Springs since before that, he can still find his way around a racetrack PDQ.

It was later, back in the pits, that Nicholas, 53, evoked the old adage about youth and enthusiasm. It took me a couple of seconds, but I finally realized he was talking about me. Weird concept, that at age 35, I could be considered “young,” but that’s how it is in vintage racing. The flesh-not to mention the iron-may be old, but it’s still plenty fast, as I’d discovered during the previous weekend’s Corsa Moto Classica roadraces, presented by AHRMA and the Garage Company.

It all began when Team Obsolete’s

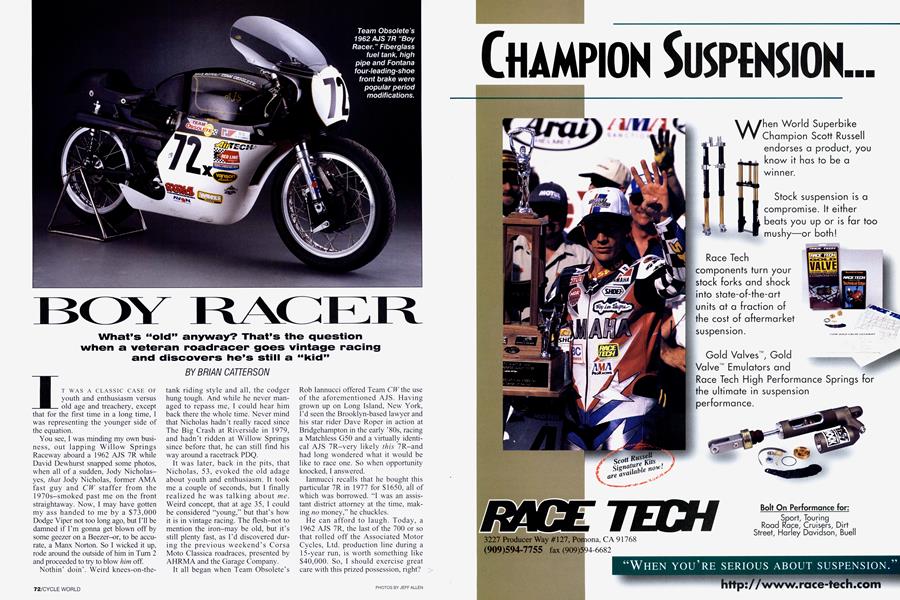

Rob Iannucci offered Team CW the use of the aforementioned AJS. Having grown up on Long Island, New York, I’d seen the Brooklyn-based lawyer and his star rider Dave Roper in action at Bridgehampton in the early ’80s, racing a Matchless G50 and a virtually identical AJS 7R-very likely this 7R-and had long wondered what it would be like to race one. So when opportunity knocked, I answered.

Iannucci recalls that he bought this particular 7R in 1977 for $1650, all of which was borrowed. “I was an assistant district attorney at the time, making no money,” he chuckles.

He can afford to laugh. Today, a 1962 AJS 7R, the last of the 700 or so that rolled off the Associated Motor Cycles, Ltd. production line during a 15-year run, is worth something like $40,000. So, I should exercise great care with this prized possession, right?

“Hell, no! Take it out and wring its neck, that’s what it’s for,” Iannucci declared.

So I did-for almost a lap, when while roosting through Turn 8 at about 100 mph, the engine suddenly quit. Suspecting a dropped valve, I pulled in the clutch and coasted into the pits, where further examination revealed that the problem was far less

severe. The sparkplug had fallen out.

“Isn’t that item number one on the pre-race checklist?” one onlooker queried.

“Why, uh, yes,” I replied under my breath, and had I actually possessed such a checklist, I may actually have checked it. But pre-race prep had consisted of handing the AJS to local Britbike tuner Bill Dunlap, with instructions to make the bike “raceready.” Dunlap stripped off the crashdamaged fairing and windscreen, sprayed and mounted replacements, spooned on some new Avon AM22s, etc., but had apparently forgotten to put a wrench on the sparkplug. That was the only thing he’d neglected, however, as the bike performed flawlessly the remainder of the weekend.

Examining the bike before that first practice session sent a chill down my spine. Was that really solder wrapped around the spokes in lieu of wheel weights? And just exactly how old were the welds on those flimsy clipons, and how many times had they been hammered straight after a crash? Like the old Mercury capsule at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C., the 7R may not look that high-tech now, but it was state-ofthe-art in its day, as purposeful as a modem Yamaha TZ250.

“The 7R was primarily intended as an over-the-counter racer for the ordinary club lad,” reads Bob Currie’s Classic British Motor Cycles, The Final Years. As such, the engine was engineered for long life, with a massive 1-inch mainshaft supported by four bearings and separate oil pumps for feed and return. It was also designed to be easy to maintain; Iannucci purports that the 7R campaigner could strip his engine down to the bottom end inside the frame, and could extract the entire lump in less than 15 minutes. Indeed, Dunlap and I found the Ajay to be

extremely easy to work on, with a valve adjustment taking all of 10 minutes thanks to the eccentric rocker spindles, and jetting changes for the single Amal carburetor taking less time than that. Gearing changes were a bit complicated, however, as accessing the gearbox sprocket requires removing the dry clutch.

Weighing in the vicinity of 300 pounds and boasting 42 peak horsepower at 7750 rpm, the T.O. AJS isn’t exactly what you’d call fast, but once up to speed, it carries it well. Given its spindly fork, frame and swingarm tubes, you’d expect the bike to be a flexi-flyer, but this is not at all the case. To the contrary, the 7R was remarkably stable at high-speed Willow Springs, and nimble to boot. In fact, the most difficult aspect of riding the bike fast was keeping the engine in its narrow, 2000-rpm powerband. Like a modern 250cc GP bike, gearing and jetting are critical.

Most AHRMA events feature a full program of racing on both Saturday and Sunday, so racers have two shots at winning. During practice, I familiarized myself with the right-side/up-for-

down shift pattern and left-side rear brake, and while I didn’t exactly set the track ablaze, I couldn’t help noticing that the only riders who passed me were on a Ducati 916 and a Honda CR750.

In Saturday’s 350cc GP race, I botched the startnot something you want to do when you’re gridded on the ninth row-lugging the AJS off the line and heading into Tum 1 dead-last. By the time I’d clawed my way up to second place,

multi-time AHRMA champ Mike Green and his West Coast British Racing Ducati had a 6-second lead, and there weren’t enough laps left to close the gap.

Sunday went much better, as I got the throttle/clutch-slippage quotient just right at the start and headed into Turn 1 ...second-to-last. More importantly, though, I was right with the pack this time, and sliced and diced my way up to second place by halfway through the first lap. And this time, when leader Green looked over his shoulder, I was right there waving back at him.

“You’re mine!” I said inside my helmet.

And he was. After following for a lap, I carried more speed through Turns 8 and 9 and outdrove Green onto the front straightaway. A lap later, I looked over my shoulder and didn’t see him at all. But there was a reason, as I found out later back in the pits: Green had retired with a broken rear wheel.

Oh well, you take the wins any way you can get them, and this one was mine-by a margin of 46 seconds, no less! For a brief moment, I felt like Mike Hailwood winning the 1961 USMC Grand Prix at Willow Springs, pulling 5 seconds per lap on the field en route to victory. Only in doing so, Hailwood had lapped something like 5 seconds quicker than I’d managed here, 36 years later. But of course, he was just 21 years old then...

Hailwood raced a Manx Norton that day at Willow, but earlier in the year, he’d very nearly given AJS what would have been its only victory at the Isle of Man TT, leading the Junior race until a wrist pin broke just 12 miles from the finish.

Back in its day, the AJS 7R was called a “Boy Racer” because it was commonly ridden by young up-andcomers. Today, the nickname is fitting in that the 7R is helping to keep aging racers young. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontPlan 2003

October 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsParking Lot At Assen

October 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCReally Nice Racebikese

October 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1997 -

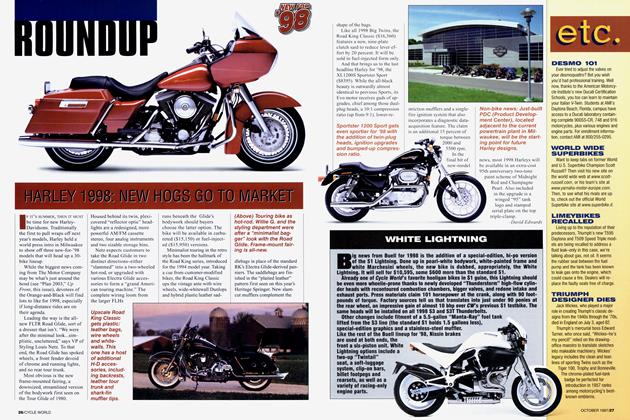

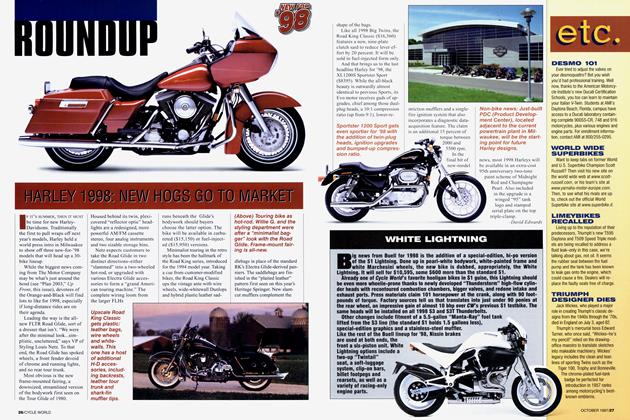

Roundup

RoundupHarley 1998: New Hogs Go To Market

October 1997 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupWhite Lightning

October 1997