Want-Ad Wonders

August 1 1989 Camron E. Bussard, David Edwards, Jon F. Thompson, Ron Griewe, Ron LawsonWANT-AD WONDERS

Your next motorcycle could be just a phone call away

NO MECHANICAL DEVICE ENTICES QUITE LIKE A JUST-minted, fresh-from-the-factory motorcycle, with the promise of thousands of miles of rousing, in-the-wind motoring yet to come. But fewer and fewer people are experiencing that thrill as the market-wide decline in new-bike sales continues.

Blame part of that decline on prices. More specifically, the high prices that—for various reasons—dealers have to charge for the bikes in their showrooms. Motorcycles today, like almost all items, are more expensive than they were yesterday. Actually, Cycle World did a little monetary sleuthing (see “The Changing Cost of Having Fun,” pg. 54) and discovered the price increase of motorcycles over the past decade isn’t really as dramatic as it seems, but the fact remains that in 1989, a buyer will have to ante up a minimum of about $3000 in order to park a new, full-size streetbike in his garage.

Unless he buys used. Used bikes have become increasingly hot commodities in the past couple of years as a result of their comparative affordability. In fact, some

dealers tell us they’ll sell more used bikes than new machines this year. So, we decided to have a look at the trend.

Now, we at Cycle World have scads more experience with new bikes than we do with used bikes. That is, after all, part of the job: testing the manufacturers’ latest models and then telling you, the readers, all about them. As a result, though, our used-bike experience came up lacking.

But no more. For this article, we didn’t just ask questions, gather quotes and then file the story. No sir, we got check-the-classifieds, dial-the-phone, kick-the-tires involved and spent real money on the five bikes on the following pages. To gauge just what was available in the universe of used bikes, we purchased motorcycles in five different price categories: $100, $250, $500, $750 and $1000. And to insure road-worthiness, we set up a 100mile group ride.

Our conclusion after looking at, bargaining for and riding these five previously owned gems? There are lots of things in life that a little money won’t buy, but a good motorcycle isn’t one of them.

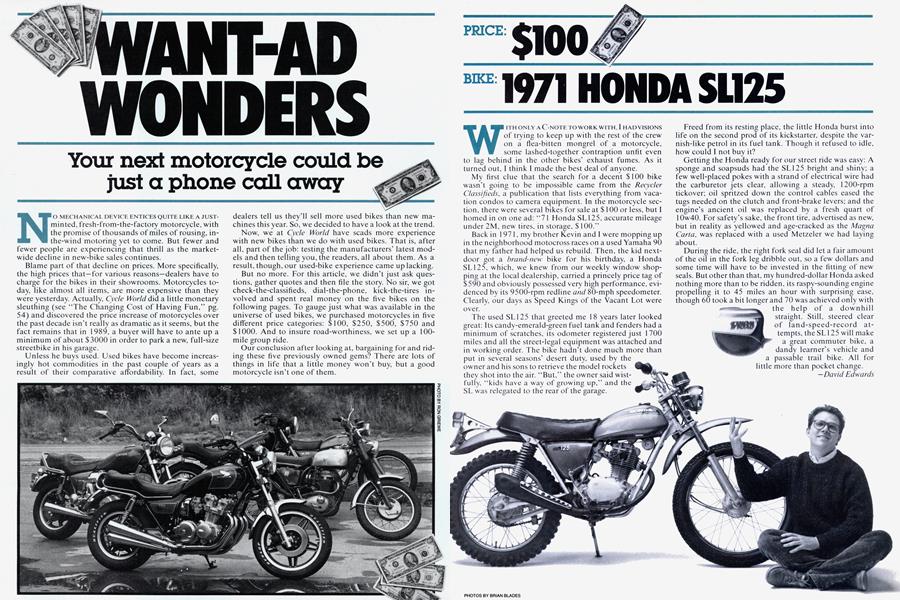

PRICE: $100 BIKE: 1971 HONDASL125

WITH ONLY A C-NOTE TO WORK WITH, I HAD VISIONS of trying to keep up with the rest of the crew on a flea-bitten mongrel of a motorcycle, some lashed-together contraption unfit even to lag behind in the other bikes’ exhaust fumes. As it turned out, I think I made the best deal of anyone.

My first clue that the search for a decent $100 bike wasn’t going to be impossible came from the Recycler Classifieds, a publication that lists everything from vacation condos to camera equipment. In the motorcycle section, there were several bikes for sale at $ 100 or less, but I homed in on one ad: “71 Honda SL 125, accurate mileage under 2M, new tires, in storage, $ 100.”

Back in 1971, my brother Kevin and I were mopping up in the neighborhood motocross races on a used Yamaha 90 that my father had helped us rebuild. Then, the kid nextdoor got a brand-new bike for his birthday, a Honda SL125, which, we knew from our weekly window shopping at the local dealership, carried a princely price tag of $590 and obviously possessed very high performance, evidenced by its 9500-rpm redline and 80-mph speedometer. Clearly, our days as Speed Kings of the Vacant Lot were over.

The used SL125 that greeted me 18 years later looked great: Its candy-emerald-green fuel tank and fenders had a minimum of scratches, its odometer registered just 1700 miles and all the street-legal equipment was attached and in working order. The bike hadn’t done much more than put in several seasons’ desert duty, used by the owner and his sons to retrieve the model rockets they shot into the air. “But,” the owner said wistfully, “kids have a way of growing up,” and the SL was relegated to the rear of the garage.

Freed from its resting place, the little Honda burst into life on the second prod of its kickstarter, despite the varnish-like petrol in its fuel tank. Though it refused to idle, how could I not buy it?

Getting the Honda ready for our street ride was easy: A sponge and soapsuds had the SL125 bright and shiny; a few well-placed pokes with a strand of electrical wire had the carburetor jets clear, allowing a steady, 1200-rpm tickover; oil spritzed down the control cables eased the tugs needed on the clutch and front-brake levers; and the engine’s ancient oil was replaced by a fresh quart of 10w40. For safety’s sake, the front tire, advertised as new, but in reality as yellowed and age-cracked as the Magna Carta, was replaced with a used Metzeler we had laying about.

During the ride, the right fork seal did let a fair amount of the oil in the fork leg dribble out, so a few dollars and some time will have to be invested in the fitting of new seals. But other than that, my hundred-dollar Honda asked nothing more than to be ridden, its raspy-sounding engine propelling it to 45 miles an hour with surprising ease, though 60 took a bit longer and 70 was achieved only with

the help of a downhill straight. Still, steered clear of land-speed-record attempts, the SL 125 will make a great commuter bike, a dandy learner's vehicle and a passable trail bike. All for little more than pocket change.

David Edwards

PRICE: $250 BIKE: 1982 YAMAHA 400

SOME MOTORCYCLES JUST DON’T GET ANY BREAKS. Life starts out being hard and things just get worse and worse. Example: my friend Miles the Yamaha 400. I’m not really sure where it came from originally, who purchased it or why, but I do know that Miles wasn’t a pampered plaything, sheltered in a warm garage well-stocked with lubricants and polishes. Miles worked hard for a living. It was in and out of foster homes and even did some time in the Big House for a crime it didn’t commit.

I also know the machine was a commuter, racking up more than 50,000 miles, mostly on the freeway, from the looks of things. Then, as closely as I can piece together, something finally gave up in the tired engine. It went into a shop, was repaired and then ignored. Even though Miles had given its all to the original owner, the shop’s bill wasn't paid. So the shop sold the bike for the amount of the repairs. The next owner was a poor college student who had a night job some 60 miles from home. More freeway commuting followed, combined with virtually no maintenance. Then, poor old Miles the Maxim was stolen.

Things went from bad to worse for the bike. No one knows where it went and what it did during the months it was missing, but chances are it wasn’t treated with care and consideration. And when the police finally recovered it, they couldn’t figure out who the rightful owner was due to its convoluted registration history. Miles sat and sat, and in the meantime the wheel-less college student purchased a used Kawasaki 454. By the time the police figured out who Miles’ owner was, the bike had accumulated a $230 storage bill.

And that’s where I came in. I had placed an ad in the newspaper, fishing for a good transportation motorcycle. Because the student already had his new bike, he was happy to sign the worn Maxim 400 over to me for the amount of the storage bill.

Miles’ traumatic experiences have left deep scars on its personality. It still runs as strong as ever, but its wheel bearings are rusted, its swingarm bushings are loose and the ignition switch will turn with any screwdriver or butter knife. And worst of all, it’s ugly. Not just faded-paint ugly, mind you, but deep-down ugly, the kind of look a teenage junkie gets after a few hard years on the street.

On the staff ride, Miles drew very little attention—just the occasional rejection when I would offer it to anyone else for a quick test ride. The others would laugh at its scuffed paint, torn seat, broken badges and leaky fork. And whenever I joined in with their cruel humor, a quick look at Miles’ sad profile would instantly punish me with a sharp jab of guilt. So far, all it’s known is how to be ridden hard, neglected, abandoned, stolen and unwanted. Now let’s see how it reacts to a little grease and a lot of TLC.

Ron Lawson

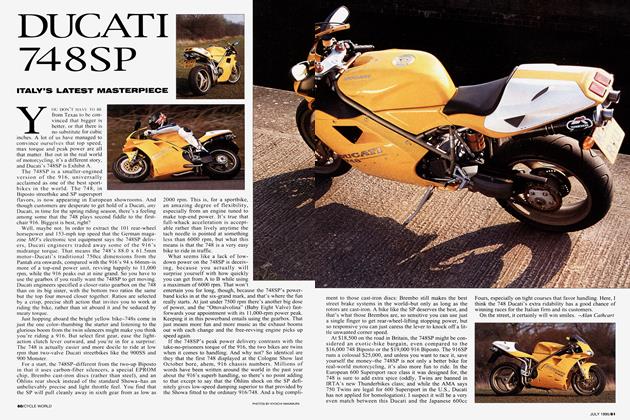

PRICE: $500 BIKE: 1969 BSAVICTOR 441

FINDING A $500 MOTORCYCLE WITH SOME CHARACTER and potential for adventure sounded like trouble. Then I found the 1969 BSA Victor you see here. It’s certainly got character. It’s certainly provided adventure. And it cost $400.

Though tatty in some respects, this neoclassic Thumper started first kick, idled with a reassuring, maximum-decibel exhaust note and made a minimum of mechanical noise. Blimey, what a deal! Ignoring the bike’s tangled miasma of English and Japanese wiring and electrical components, we forked over the moolah and hauled the Victor to the CW garage.

First things first: Yes, the Victor, like any good British motorcycle, leaks oil. But the sound of every drop as it hits the garage floor is to us as the tone of a fine brass bell. It’s the sound of authenticity.

That aside, its engine and transmission seemed fine. But the rest of the Victor was in seriously ugly condition. Its frame was lipstick red, it wore gold-anodized handlebars long enough to dislocate elbows, and its throttle and clutch cables were badly worn. It was innocent of a frontbrake lever and cable, and its clutch lever was badly bent. Two new hand levers, new handgrips, new throttle, clutch and front-brake cables, plus a set of alien-head bolts for the engine sidecovers, cost $75. A discarded MX handlebar was free.

More serious problems lurked about the area of the swingarm, which was bent, as were both shocks. It so happened that Mr. Editor Edwards possessed a spare set of BSA shocks and was willing to donate them. The swingarm was straightened by Senior Editor Ron Griewe, who keeps a 30-ton press and other odd machine tools in his garage. The only cost for his help was the need to endure his wisecracks about this little British prize.

And now, 16 hours of labor later, our BSA Victor forms the basis of just the sort of project some riders would kill for: A motorcycle that’s easy to work on and which has bottomed out on its depreciation curve.

The 100-mile ride? Uh, we didn’t quite make it. The Victor ran out of electricity at Mile 78, to the pitiless hoots of my riding companions. Hey, nobody said riding and maintaining a 20-year-old BSA is effortless. But parts are easy to find, and if you know where to look, so are the required Whitworth tools and the shop manuals.

For those of us who like to potter about with old bikes, motorcycles like this Victor still deliver satisfaction in spades, though perspective is important: These old bikes don’t deserve to be icons. In many cases, they’re pretty awful. But they can be great fun to ride and work on, and that’s why I’ll persevere with the Victor. Laura, my wife, thinks it’s because I thrive on adversity. She might be right. Few things are as adverse as a British motorcycle. Or more perversely satisfying. Especially at $475.

Jon F. Thompson

PRICE: $750 BIKE: 1981 YAMAHA 850

THE HEAT WAS ON. LESS THAN A WEEK BEFORE WE were scheduled to go on our used-bike ride, while the others were busy waxing and buffing their acquisitions, I was still searching.

A sheriff’s department auction had advertised vehicles, so I attended. But where were the vehicles? “Got a bunch of bicycles; no cars or motorcycles,” answered the deputy.

My next stop was a storage auction. No motorcycles there. A large swap meet at a drive-in-movie lot proved equally disappointing.

In desperation, I scanned the newspapers. An 1 100 Yamaha caught my eye. “What’s the mileage?” I asked its owner over the phone.

“Well,” he began, “I’m not really sure. Took the tach and speedometer off three years ago: They got kind of oval-shaped when I Tboned a car. The crash bent the forks back, too, but it handles fine; ride it to work every day.” I'm sure.

A “clean” Kawasaki 1000 for only “$850, firm,” sounded good. But when I looked at the bike, I wondered how anyone could so completely trash a bike in only 18,000 miles. I wouldn’t have hauled it home for free.

I almost didn’t call about the last bike on my list, a 1981 Yamaha 850 Special with 20,000 miles on it. But deadline was fast approaching, so I decided to have a look. A nice, gray-haired gentleman greeted me, a retired fireman, it turned out, who'd obviously spent a lot of time fettering over his bike. The 850 was so nice I bought it, even though the old guy wouldn’t budge on his asking price and I ended up going $50 over budget.

And I’m glad I did. The big 850 Triple is a wonderful powerplant, at idle emitting a rolling thump as the engine shakes in its rubber mountings. Above idle, the engine smooths out nicely and concentrates on producing torque—gobs of it, so much that the 5-speed transmission seldom needs to be shifted out on the open road.

The chassis wrapped around that engine does seem a trifle outdated when compared to some of today’s suppleriding chassis, but it gets the job done, with an air-adjustable fork, triple-disc brakes and shaft final drive. My only concerns centered around worn-out shocks and a front tire that would soon need replacing. Still, with new shocks and rubber, the Yamaha would be ready to ride anywhere, and for about $ 1000, including fix-up, that’s a heck of a deal.

When I look at the 850 Special's gleaming chrome and paint, I can’t help remembering all of the junk I saw while shopping for it. The 850 proves that it is possible to buy a clean, tight, reliable, well-cared-for motorcycle for $750 or so. You just have to be willing to sift through some lumps of coal to find your diamond.

Ron Griewe

PRICE: $1000 BIKE: 1981 HONDACB750

LOCATING A GOOD MOTORCYCLE FOR $1000 WAS NO problem; all I needed was a little bit of luck. I got it, strangely enough, when calling about a $900, 1979 CB750 that had already been sold. Fortunately, the man must have heard my sigh, because just before I hung up, he asked, “Did I tell you about the other one?”

I snapped to attention when he explained that his father had decided to sell his 1981 Honda CB750 Custom but hadn’t even put an ad in the paper yet. Almost before he finished the sentence, I was out the door. When I arrived at his house, the garage was open, the bike stuffed against a wall, its rear tire nearly flat, its front tire with no tread whatsoever on the sides, a sure sign of acute underinflation. Both fork seals were leaking, and the entire bike suffered under a coat of grime.

On closer inspection, though, I saw a solid bike hidden beneath years of neglect. It ran great; its dohc, 16-valve engine smooth and quiet. It had only 5200 miles on the odometer and still had all the original equipment, right down to the stick-on warning labels. It also sported a windscreen, a crash bar and a luggage rack.

I picked up the 750 for $900 and headed back to the CW garage with $100 left in my budget. I then mail-ordered tires from Donelson Cycles in St. Louis, Missouri, which was running a special on Dunlop Qualifiers for $89.95 a pair. At that price, I decided to splurge, so I ordered a set with raised, white letters for an extra $ 10. With the nextday shipping and tax, and a $20 charge at a local shop for mounting the tires, I was over my budget by $50.

With the tires taken care of, I went back to cleaning the bike, a task completed with a couple hours of elbow grease, a jar of Naval Jelly, a bottle of Formula 409 spray cleaner and liberal applications of Turtle Wax and Armor All. Once the dirt was off and the wax was on, the chrome glistened, the aluminum engine cases were spotless and the fuel tank and sidecovers looked brand new, with nary a scratch or dent. I preened like a kid with a new puppy, pointing to the four chromed, upswept mufflers whenever anyone ventured into the garage.

But although it looked showroom fresh, started up like new and sounded great, a quick ride made me realize how far motorcycles have come in the last eight years. This bike would get pulverized by any of today’s 600s and could be outbraked by almost any current motorcycle. On the other hand, the CB750 is more commodious than a lot of modern bikes, with a better seating position and enough room to carry a passenger in comfort.

In the end, my CB750 Custom proved to be a bike worth every penny I spent on it. It’s a fun motorcycle to ride, mechanically sound and, by almost any standard, a remarkably versatile machine. I could ride it for several years and do nothing more than wax it and perform some basic maintenance. And from a $ 1000 motorcycle, there’s little more you could ask.

Camron E. Bussard

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

August 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

August 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupNew, Top-Secret Triumph Revealed

August 1989 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupFor Japan Only: the High-Tech 250s

August 1989 By David Edwards