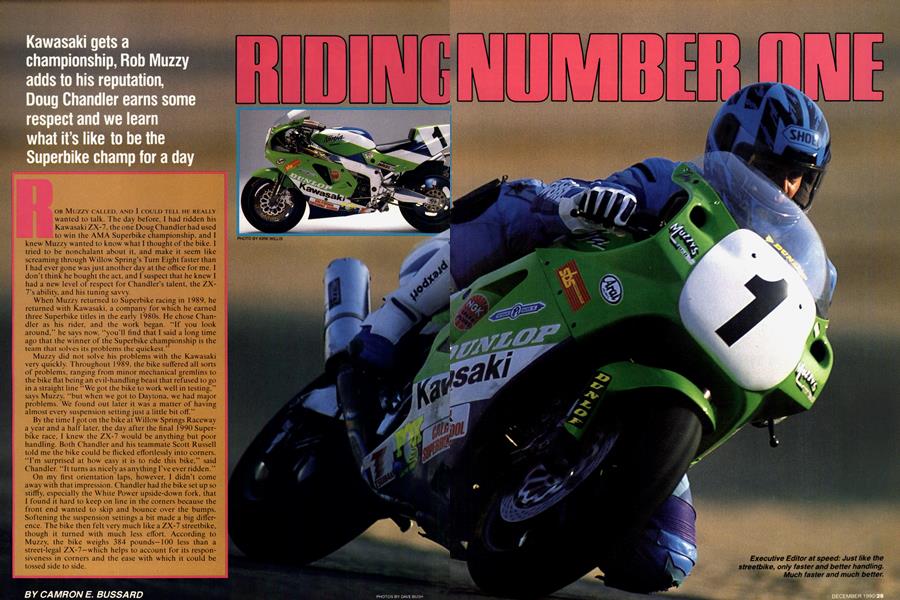

RIDING NUMBER ONE

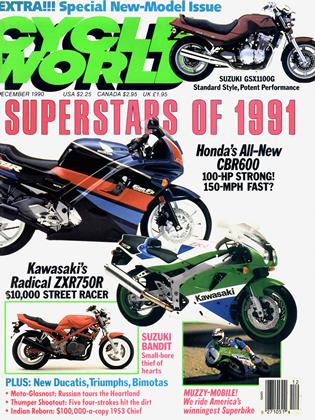

Kawasaki gets a championship, Rob Muzzy adds to his reputation, Doug Chandler earns some respect and we learn what it’s like to be the Superbike champ for a day

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

ROB MUZZY CALLEED, AND I COULD TELL HE REALLY wanted to talk. The day before, I had ridden his Kawasaki ZX-7, the one Doug Chandler had used to win the AMA Superbike championship, and I knew Muzzy wanted to know what I thought of the bike. I tried to be nonchalant about it, and make it seem like screaming through Willow Spring's Turn Eight faster than I had ever gone was just another day at the office for me. I don't think he bought the act, and I suspect that he knew I had a new level of respect for Chandler's talent, the ZX-7's ability, and his tuning savvy.

When Muzzy returned to Superbike racing in 1989, he returned with Kawasaki, a company for which he earned three Superbike titles in the early 1980s. He chose Chandler as his rider, and the work began. “If you look around," he says now, “you'll find that I said a ïong time ago that the winner of the Superbike championship is the team that solves its problems the quickest."

Muzzy did not solve his problems with the Kawasaki very quickly. Throughout 1989. the bike suffered all sorts of problems, ranging from minor mechanical gremlins to the bike flat being an evil-handling beast that refused to go in a straight line “We got the bike to work well in testing," says Muzzy, “but when we got to Daytona, we had major problems. We found out later it was a matter of having almost every suspension setting just a little bit off."

By the time I got on the bike at Willow Springs Raceway a year and a half later, the day after the final 1990 Superbike race, I knew the ZX-7 would be anything but poor handling. Both Chandler and his teammate Scott Russell told me the bike could be flicked effortlessly into corners. “I'm surprised at how easy it is to ride this bike," said Chandler. “It turns as nicely as anything I've ever ridden."

On my first orientation laps, however. I didn't come away with that impression. Chandler had the bike set up so stiffly, especially the White Power upside-down fork, that I found it hard to keep on line in the corners because the front end wanted to skip and bounce over the bumps. Softening the suspension settings a bit made a big difference. The bike then felt very much like a ZX-7 streetbike, though it turned with much less effort. According to Muzzy, the bike weighs 384 pounds—100 less than a street-legal ZX-7—which helps to account for its responsiveness in corners and the ease with which it could be tossed side to side.

Once 1 got used to the handling. I was able to pay closer attention to the ZX's power. Chandler had said. “Just shift it at 1 3.000 rpm. there’s nothing above that.” I thought he was joking, especially after I rode the bike and found that shifting at 11.000 gave me more speed than I wanted. But when I let the engine pull up to 13,000 rpm, 1 uncovered the real powerband. The Muzzy-fettled motor was strong enough from 8000 rpm on up, but past 1 1.000, it was stunning, accelerating harder than any built 750 I have ever ridden, and easily a match for most 1000 and 1 lOOcc streetbikes.

But the power was far from unmanageable, with a delivery almost as smooth as the road-going ZX-7's. The engine, says Muzzy with all apprarent honesty, isn't really all that exotic. Basically, it's been bored to displace an AMAlegal 757cc. The compression ratio has been bumped up to 13:1. It uses Kawasaki racing-kit rods and Muzzy pistons and cams. Also, the crank is 4.4 pounds lighter. About the only really trick parts are the Keihin 39mm flat-slide carburetors. Muzzy started the season with 38mm CVs, but couldn't get them to work properly, so he switched to 40mm Mikunis at Daytona. Then, just before the Road Atlanta race, he began using the Keihins. Muzzy claims the flat-slides add no peak power—which he says for this bike is somewhere over 120—but let the bike accelerate harder, thus yielding faster lap times.

He claims his exhaust system, however, adds about 5 horsepower. It's a titanium pipe with stepped headers that gradually increase in size on the way to the collector. “Our engine and the factory engine raced in Japan and Australia are just about the same,” says Muzzy, “except for the pipe, which gives us a bit more power.”

I didn't think the bike needed any more power; I was already lapping faster than I had ever gone at Willow, and to be honest. I didn't really want to go carry any more speed into the corners. I'd hate to be remembered as the journalist who splattered Kawasaki’s championship-winner just 24 hours after it had secured the title. For that reason, I loved the brakes. In fact, every time I popped up into the airstream and clinched the lever, I found I was braking way, way too early, and could have gone deeper into every corner without inducing more rider trauma. The Performance Machine calipers lacked feel at the initial application, but clearly made up for that in bite and stopping power.

My strongest impression of the bike by the time that I parked it was that it was cabable of performance levels the street ZX-7. and I. will never dream of. I may have felt like a hard-charging hero, but at my speeds, the Kawasaki was barely breaking a sweat, and I ended up with as much admiration for the rider who could push this bike up to and beyond its lofty limits as I did for the machine itself. And, in truth, the development of the bike is closely tied to that of Chandler.

As Muzzy continued to improve the quick green ZX, Chandler was also coming along. Recognized for the last few years as a rider of great talent. Chandler had not capitalized on his ability. A northern California flat-tracker, he began working with roadrace guru Keith Code back in 1984, and the seemingly never-ending battle w'as to get Chandler to become more aggressive, particularly in practice sessions. But it was not until early in the 1989 season that Chandler began to get his asphalt act together. “Doug has a riding code of honor that dictates how' fast his times should be,” says Code. “He doesn't work against his bike or his riding style, but against himself.”

Muzzy adds that until Chandler began to ride for him, “He didn’t have the confidence to ride harder than the machine was capable. He had to develop that. All I tried to do was give him a mount and situation that allowed him to do the best he could.”

That helped Chandler immensely. “1 always felt I could win.” says Chandler. “But my biggest problem was that I had trouble sorting out the machine. Rob helped me there, and I began to get a much better feel for what was going on underneath me. Then I was able to get going right from the drop of the flag, because 1 had a lot more confidence.” Clearly, the experience with Muzzy and Kawasaki has been good for Chandler, and he has blossomed into a world-class racer. At the Superbike round in Topeka, Kansas, three-time world champ Freddie Spencer said, “1 think Doug could do real well on a 500 GP bike. He does have the talent.”

On the one hand. Chandler’s progress is good to see, but on the other, it means that if he follows the traditional path of the AMA Superbike champion, he will leave racing in the States for the more lucrative shores of Europe and contest either the 500cc GPs—which is what he hopes for—or head for the battles raging in World Superbike competition. World Superbike is a logical step for Chandler, and there are rumors of a full-fledged Kawasaki effort if Chandler decides he wants to stay on four-strokes.

Chandler’s achievements in 1990 were wrapped up in the success of the ZX-7 racebike and Rob Muzzy’s experience as a tuner and race-team manager. As much as any championship in recent years, this one was a balance of three crucial parts: A tuner, a rider and a motorcycle peaking at the same time, blending experience, talent and mechanical excellence into one very hard-to-beat package. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue