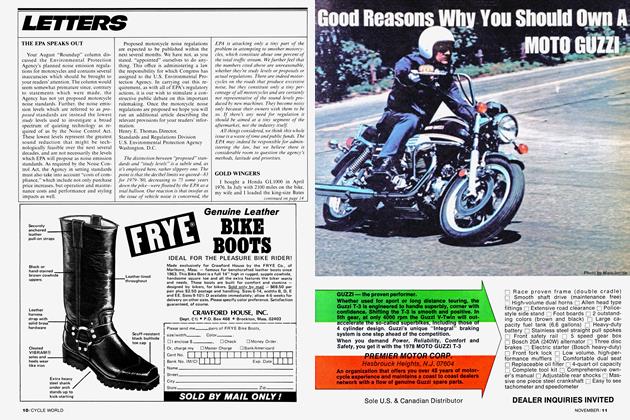

NEW IDEAS IN BOOTS AND HELMETS

FULL BORE TOUR AND RACE BOOTS

Footwear has long been a problem for the daily and touring rider. Shoes aren't safe, they quickly become scuffed and stained and the wind flaps your legs without mercy. Work or hiking boots are clumsy and don't look right in the office. Racing boots are generally fragile and don't hold up to daily use.

Full Bore boots are supposed to cure all that. They're built like walking boots, with an arch support and corrugated non-slip sole. They're high enough to be safe. The outside dimensions are smaller than those of most boots, that is, the size 9 Full Bore boot is a more compact package than is an engineer or cowboy boot. The Full Bores are slimmer, which lets your trouser leg drape over the tops for formal wear, and because these boots fasten with a zipper back, you can tuck your cuffs into the boot top while riding.

The boots use racing-style snaps to cover the zipper, to reduce the chances of having the boots snagged or working themselves open. Finally, they look enough like shoes to be worn to work.

Three of the staff members here have these boots. After several months of use, all three say their boots are holding up well and need no more than an occasional polish. The only complaints so far are that the color choice is limited to blue. The blue dye does ajob on white socks until the boots have been worn for a while, and because the boots are made in Italy, the sizing seems to vary with what we're used to in the U.S. Two of our pairs fit well, the other is a bit tight.

Worth looking at, at any rate. Sizes are 5 through 14, in, medium (B and C) or wide (D and E) widths, and the price is $49.95. The boots should be in stock at your nearest Fi~11 Bore dealership or you can get the name of a dealer from Full Bore East, 780 Main St., Holden, Mass. 01520, or Full Bore West, 13712 Alma Ave., Gardena, Calif. 90249.

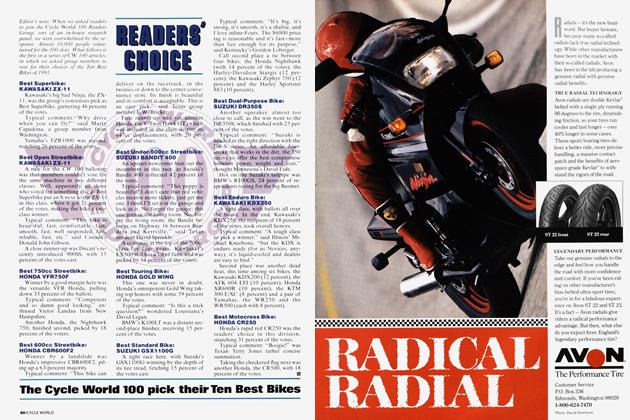

SNELL '75 HONDALINE

Carefully touching wood (or fiberglass) we must make a distinction here: This is not a full evaluation in the normal sense and we hope never to fully evaluate a crash helmet's most important function, that of protecting the rider in event of a crash.

Instead, this is a partial evaluation and a news item.

First, the news. Near on 20 years ago some racing fans with medical back grounds became concerned with the lack of valid information about helmets. They created the Snell Foundation, a non-profit group dedicated to setting performance standards for helmets and to scientifically testing production helmets against those standards.

As the helmet makers and testers gained experience and came out with better helmets, so have the Snell Foundation's standards been made better and tougher. The theory has always been to set new requirements. When two or more man ufacturers can meet the requirements, the requirements become the new standard.

In 1975 the foundation issued what's now known as "Snell `75" standards. They are similar to early standards in that they demand each helmet absorb certain im pacts, not deteriorate, have straps that don't allow the helmet to slip or fall off, etc.

While this was going on the federal government also drew up some helmet standards. Without getting too technical or biased, the federal rules weren't quite as stringent as the Snell rules. In brief, the federal standards called for shock absorp tion at lower impact and with a time limit, i.e. how hard the test head could be hit for how long. These rules also have been modified and improved, the latest govern ment tests being known as DOT-218.

Both Snell `75 and DOT-218 are valid standards. Because they aren't the same, there was some question as to whether a helmet could be made which meets both Snell and DOT. The world doesn't actually need a double standard, true, but because the Snell is a tougher test while DOT is likely to become the rule by which road

helmets are certified by the several states, a double standard helmet would be nice to have.

Here one is. One of four, at this writing.

Hondaline, Bell, Shoei and Simpson are now selling helmets certified under Snell ’75 tests and certified as meeting the DOT218 tests in the Medium size. (Confusing? There is no DOT-218 test for the other head sizes, so the Small, Large and Extra Large models cannot have DOT-218 labels, even if they are built to the same design and material specifications.)

These four brands are listed here because only a certified laboratory with special instruments can conduct a valid test on a helmet. Snell and DOT do not grade helmets within their test procedure, so there is no sure way to know that Brand A absorbs more impact than Brand B. Instead, we can be sure that the double standard helmets from Bell, Hondaline, Shoei and Simpson meet the toughest tests known.

The Hondaline Hawk can serve as a sample in the argument against tougher helmet standards. There have been those who argued that when you make a helmet stronger, it must become larger and heavier. This is supposed to culminate with a helmet that’s so big and heavy that it’s a hazard in itself.

This could happen. It hasn’t happened with the Snell ’75 standard.

The Hawk shown is a fraction of an inch wider, almost one inch longer and a fraction higher than a Bell Star, used for comparision here because the staff member who just got the Hawk has heretofore worn a Star.

For this man the extra length is a plus. He has a long, narrow head and nose. Riding into a headwind with the Star has always pressed the shield against the tip of his nose. Damned irritating after an hour or so. The longer Hawk cures this.

The Hawk weighs 3 lb. 15 oz. and the Star weighs 3 lb. 9 oz. The extra insulation, etc., needed for the Snell ’75 standard doesn’t add much weight. The human head averages out at something more than 12 lb., so another six ounces isn’t likely to do any damage. Nor does the weight make itself felt while riding.

As is well known, we believe in wearing helmets. The best study into the subject indicates that wearing a helmet is good for your health, and there are hints that the helmet standards don’t make the difference we expected.

Conclusions? Not many. Our man likes the Hawk helmet and doesn’t plan to test its limits.

The good part is that the riding public now has a choice and can buy a helmet that meets a rigorous test and is certified for use on public roads. HE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSelling the Sizzle

November 1977 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1977 -

Departments

DepartmentsService

November 1977 By Len Vucci -

Features

FeaturesToo Much Government Is In Our Future

November 1977 By Lane Campbell -

Features

FeaturesItalian Spoken Here

November 1977 By Jean Crabb -

Roundup

RoundupThe Victory Continues

November 1977