Monastery

TDC

Kevin Cameron

Now THAT THE GEESE AND THE HUMmingbirds have flown, I have to think about heating my shop. That means remembering to carry three or five pieces of wood up with me, every time I go, to keep my not-too-spiffy stove working. Every year, I have to again correctly wedge a shingle into the blower casing to stop its annoying vibration. Once those things are done, and the shop has warmed to 50 degrees or so, work can begin. There is never a shortage of projects.

If I want noise, there is a crummy old vacuum-tube radio up on the wall. Because it still works, I can’t throw it away. But if I play music, it reminds me of the pickup trucks that thump and thunder through town, driven by very young men whose cap-bills are fashionably rolled, and whose sound systems deliver more power than the V-Sixes under their hoods. Not that. And if it’s news, it’s the normal unending sameness of ambiguous headlines like “Loyalist jets pound rebel strongholds,” or was it “Rebel jets pound loyalist strongholds”? Not that, either. So no radio today.

It’s nice in the shop. No one wants to join me because they are imperiled by the cancer threat of parts-washer fumes, lacquer thinner and maybe cutting-oil vapor. That’s okay.

Is this an irresponsible, elitist existence, disengaged from all the important outside realities? No, because later I’ll return to the house and the roar of the realities will more than make up for my short absence. If the ship of state has veered off-course because my oar was momentarily dragging in the water, I will have my opportunity to row it all back straight.

Right now, though, I have to make a bronze bushing for this fork leg. Back in 1969, Yamaha remaindered all these fine TD1 front suspensions: “Fork assy, comp., special clearance price $12.50.” No one wanted them then because the design was already six years old and obsolete. What am I doing making parts for one now? Antique parts are like money invested at bank interest. This fork was maybe $60 to the dealer back in 1967, but its value today (to those who care) is basically what it would cost to have it made from scratch, entirely by hand.

Here is a suitable piece of bushing stock, and here is an original part from another bike to act as an engineering drawing. Now I have to reverse the chuck jaws to hold this stock, and find and maybe sharpen a proper toolbit.

The wind’s coming up. I can tell because the partial vacuum of its passage over my shed roof lifts the tarpaper, producing a wet unsticking sound. My shop wants to be a wing. I’ll just rough this down to within .005 of dimension, drill the center hole, then cut the grooves for the piston ring and the one-way valve. Getting going on a project is always hard for me, but once the chips are sparkling in the light as they pour off the tool, a pleasant frame of mind arrives. I’m having a good time. Why is that? When I’m away from the shop for a long time, as I am when the computer keyboard requires my hours, I forget the shop and my fingernails become dangerously clean. Just as it takes a certain amount of energy to drag an electron out of a hot sparkplug electrode, I have a work function to overcome in returning to my cold monastery, the shop. It’ll take hours for that clunky stove to overcome the chill. I’ll have to face all the things I should have done before now. The shop’s a mess, but the keyboard is always neat. The usual excuses.

But once they’re overcome and the toolbit is actually in the cut, I’m home. I can do this. I used to do it all the time. I even enjoy it. There, another .003 and I should be there. I switch from the rough measure of the vernier calipers to one of my motley collection of micrometers. Pretty close. Bearings in fork legs have to be loose because the tubes bend under braking loads and will bind close-fitted slider bearings. Like the manufacturers themselves, I learned this the hard way. On this 32-year-old assembly, I am going to allow .003-inch. Recently at Daytona, 1 was pleased to find that ultra-stiff modern upside-down forks require clearances even larger than this. Truth is truth.

This lathe I’m using was, in a sense, a gift from a rider. After the Talledega National in 1974, rider Jim Evans, then 19, took me out behind one of the long garage-area sheds. He peeled some large bills off of his third-place prize money and held it out to me. “Here,” he said, “you earned this.” Mumbling something inadequate about Jim’s tremendous ride that day being a reward for us all, I accepted. Later, when I saw a used 10-inch South Bend lathe for sale, I pulled out those bills and brought home this machine. Standing here, cutting metal, I am hearing what untold thousands of old-time machinists heard all their working lives—the periodic tick-tick as the metal claw joint in the drive belt passes over the pulleys. No, it’s not CNC and it’s from another era, but it will whip up a fork bushing that will work. I brush the chips off the compound.

I go to the windows in the overhead door and look out. My wife’s car is gone. Has she gone to the store? Once I’m on the task, it’s just as hard to unstick from it as it was to get up here in the first place. I’ve been told that I resemble small children in this respect. Transitions aren’t easy. If I remind myself that she may bring back Italian-style roast beef and our favorite bread, it will be easier to cheerfully, sincerely say “Okay!” when my youngest son arrives as messenger with the news that it’s time for lunch. And now I have this swell bushing in my hand. I can look forward to pinning it to the fork leg and being able to assemble the whole front end at last. Sandwich and conversation first. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontArkansas Travelers

January 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOld Bikes: the Gift That Keeps On Giving

January 2000 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

January 2000 -

Roundup

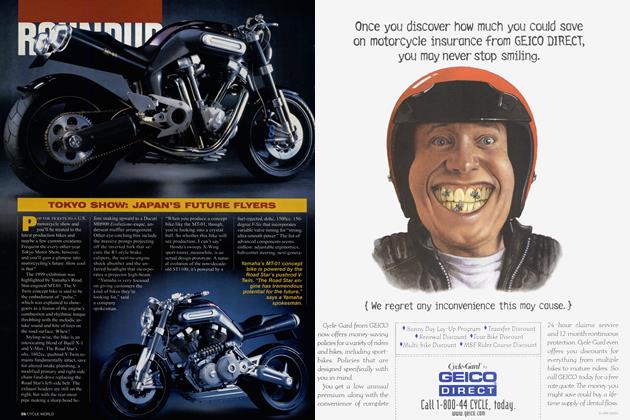

RoundupTokyo Show: Japan's Future Flyers

January 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupHornet Gets Sporty

January 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

January 2000