Kickback

TDC

Kevin Cameron

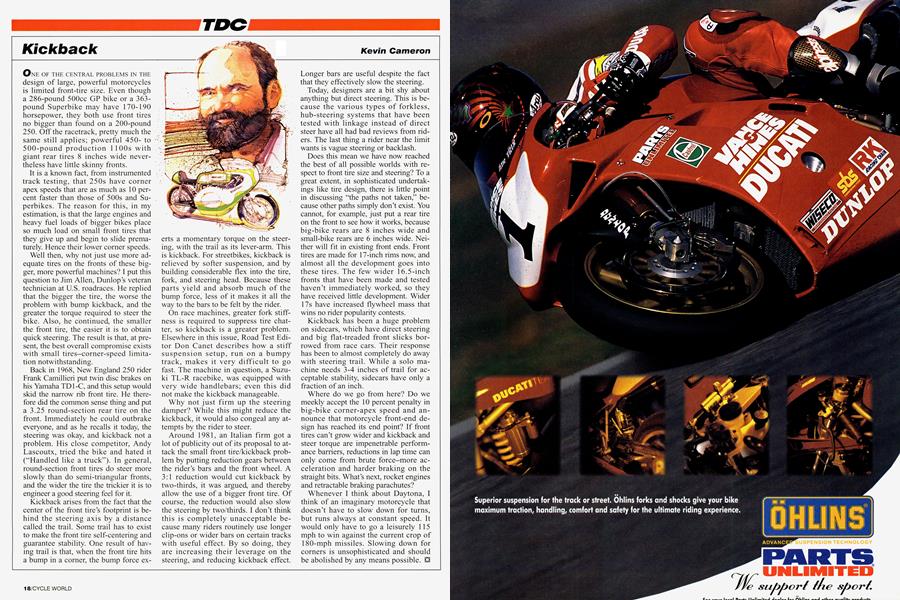

ONE OF THE CENTRAL PROBLEMS IN THE design of large, powerful motorcycles is limited front-tire size. Even though a 286-pound 500cc GP bike or a 363pound Superbike may have 170-190 horsepower, they both use front tires no bigger than found on a 200-pound 250. Off the racetrack, pretty much the same still applies; powerful 450to 500-pound production 1100s with giant rear tires 8 inches wide nevertheless have little skinny fronts.

It is a known fact, from instrumented track testing, that 250s have corner apex speeds that are as much as 10 percent faster than those of 500s and Superbikes. The reason for this, in my estimation, is that the large engines and heavy fuel loads of bigger bikes place so much load on small front tires that they give up and begin to slide prematurely. Hence their lower corner speeds.

Well then, why not just use more adequate tires on the fronts of these bigger, more powerful machines? I put this question to Jim Allen, Dunlop’s veteran technician at U.S. roadraces. He replied that the bigger the tire, the worse the problem with bump kickback, and the greater the torque required to steer the bike. Also, he continued, the smaller the front tire, the easier it is to obtain quick steering. The result is that, at present, the best overall compromise exists with small tires-corner-speed limitation notwithstanding.

Back in 1968, New England 250 rider Frank Camillieri put twin disc brakes on his Yamaha TD1-C, and this setup would skid the narrow rib front tire. He therefore did the common sense thing and put a 3.25 round-section rear tire on the front. Immediately he could outbrake everyone, and as he recalls it today, the steering was okay, and kickback not a problem. His close competitor, Andy Lascoutx, tried the bike and hated it (“Handled like a truck”). In general, round-section front tires do steer more slowly than do semi-triangular fronts, and the wider the tire the trickier it is to engineer a good steering feel for it.

Kickback arises from the fact that the center of the front tire’s footprint is behind the steering axis by a distance called the trail. Some trail has to exist to make the front tire self-centering and guarantee stability. One result of having trail is that, when the front tire hits a bump in a corner, the bump force exerts a momentary torque on the steering, with the trail as its lever-arm. This is kickback. For streetbikes, kickback is relieved by softer suspension, and by building considerable flex into the tire, fork, and steering head. Because these parts yield and absorb much of the bump force, less of it makes it all the way to the bars to be felt by the rider.

On race machines, greater fork stiffness is required to suppress tire chatter, so kickback is a greater problem. Elsewhere in this issue, Road Test Editor Don Canet describes how a stiff suspension setup, run on a bumpy track, makes it very difficult to go fast. The machine in question, a Suzuki TL-R racebike, was equipped with very wide handlebars; even this did not make the kickback manageable.

Why not just firm up the steering damper? While this might reduce the kickback, it would also congeal any attempts by the rider to steer.

Around 1981, an Italian firm got a lot of publicity out of its proposal to attack the small front tire/kickback problem by putting reduction gears between the rider’s bars and the front wheel. A 3:1 reduction would cut kickback by two-thirds, it was argued, and thereby allow the use of a bigger front tire. Of course, the reduction would also slow the steering by two/thirds. I don’t think this is completely unacceptable because many riders routinely use longer clip-ons or wider bars on certain tracks with useful effect. By so doing, they are increasing their leverage on the steering, and reducing kickback effect.

Longer bars are useful despite the fact that they effectively slow the steering.

Today, designers are a bit shy about anything but direct steering. This is because the various types of forkless, hub-steering systems that have been tested with linkage instead of direct steer have all had bad reviews from riders. The last thing a rider near the limit wants is vague steering or backlash.

Does this mean we have now reached the best of all possible worlds with respect to front tire size and steering? To a great extent, in sophisticated undertakings like tire design, there is little point in discussing “the paths not taken,” because other paths simply don’t exist. You cannot, for example, just put a rear tire on the front to see how it works, because big-bike rears are 8 inches wide and small-bike rears are 6 inches wide. Neither will fit in existing front ends. Front tires are made for 17-inch rims now, and almost all the development goes into these tires. The few wider 16.5-inch fronts that have been made and tested haven’t immediately worked, so they have received little development. Wider 17s have increased flywheel mass that wins no rider popularity contests.

Kickback has been a huge problem on sidecars, which have direct steering and big flat-treaded front slicks borrowed from race cars. Their response has been to almost completely do away with steering trail. While a solo machine needs 3-4 inches of trail for acceptable stability, sidecars have only a fraction of an inch.

Where do we go from here? Do we meekly accept the 10 percent penalty in big-bike corner-apex speed and announce that motorcycle front-end design has reached its end point? If front tires can’t grow wider and kickback and steer torque are impenetrable performance barriers, reductions in lap time can only come from brute force-more acceleration and harder braking on the straight bits. What’s next, rocket engines and retractable braking parachutes?

Whenever I think about Daytona, I think of an imaginary motorcycle that doesn’t have to slow down for turns, but runs always at constant speed. It would only have to go a leisurely 115 mph to win against the current crop of 180-mph missiles. Slowing down for corners is unsophisticated and should be abolished by any means possible. □