The Lost Manx

UP FRONT

David Edwards

LIKE ALL SAD STORIES, THIS ONE HAS A happy beginning.

The year is 1960 and crew-cut Dave Jorgensen, freshly matriculated from university, is sniffing around a small farming town in western Nebraska. He’s on the trail of a Manx Norton. Not just any Manx, mind you, but the very same works 500cc Single used by hotshoe Dick Klamfoth to win the Daytona 200 beach race in 1951. Word is that the resident sausage maker/Norton mechanic has the bike.

“When I arrived at his farm there was nobody home, so while I was waiting around I peered into the chicken coop and-wow/-there sat a Gardengate Manx, covered in droppings,” Jorgensen, now 62, remembers.

No stranger to Nortons, he had run a street-racer Manx in the late ’50s, “set up to chase the Gold Stars out of town,” but it was sold to pay for school expenses. “I immediately regretted the move since I figured I’d never find another one,” says Jorgensen.

When not processing pig innards, the owner of the chicken-coop Manx apparently used it to terrorize the local Indian and Harley contingent. “Oh, I’ve had a lot of fun with it,” he told Jorgensen. “The boys with their big fancy bikes have had a good look at the rear end of my Manx many times!”

Mr. Sausage acquired the bike from a down-on-his-luck dirt-tracker plying the Midwest’s county-fair circuit. The exKlamfoth engine came with two framesa rigid for dirt and the largely unloved Gardengate for roadracing (“Handles just like my garden gate,” someone said, “...with a hinge in the middle”). By the time Jorgensen arrived on scene, the rigid frame and some spare parts had been lost in a shed fire, but the streetized Gardengate was in play and for sale. “The owner decided that I had a sufficiently severe case of Manx fever and suggested a then-princely sum, to which I promptly agreed,” says Jorgensen.

The frame may have been lacking, but not the bevel-drive dohc motor-a “double-knocker” in Brit-speak. “The engine internals were polished and beautiful, probably having been breathed upon by famed factory tuner Francis Beart,” Jorgensen relates. “The piston had been lightened, the inlet port had been worked on and an Amal GP carb replaced the original RN model. Also, a redline had been painted on the tach at 7000 rpm-the factory claimed 6200 was the limit (for customer bikes).” The engine’s serial number, F11M34115, with works assembly number NM980 stamped on the crankcase, confirmed its Daytona heritage.

What to do with such a prize? Well, in February of 1961 the United States Motorcycle Club, a short-lived rival to the AMA, hosted its “Grand Prix International” at the just-opened Daytona Speedway, and had convinced an impressive array of European stars to attend. This seemed like a good excuse to take the old Manx back to Florida where it had achieved its fame, so Jorgensen and a pit crew of three pals loaded up the Norton and headed south, happy to escape a nasty Midwestern winter.

“The USMC race at the speedway was really something special for an Iowa boy like me,” recalls Jorgensen. “All of a sudden, I was in the pits getting ready to race with the likes of Mike Hailwood (500 Manx, 250 Mondial), Tony Godfrey (Matchless G50), Mike Duff (Manx), Ed LaBelle (Rennsport BMW), the Honda factory team with their 250 Fours-nobody at Daytona had ever seen 250s run like that!-plus a host of others that I can’t remember anymore.”

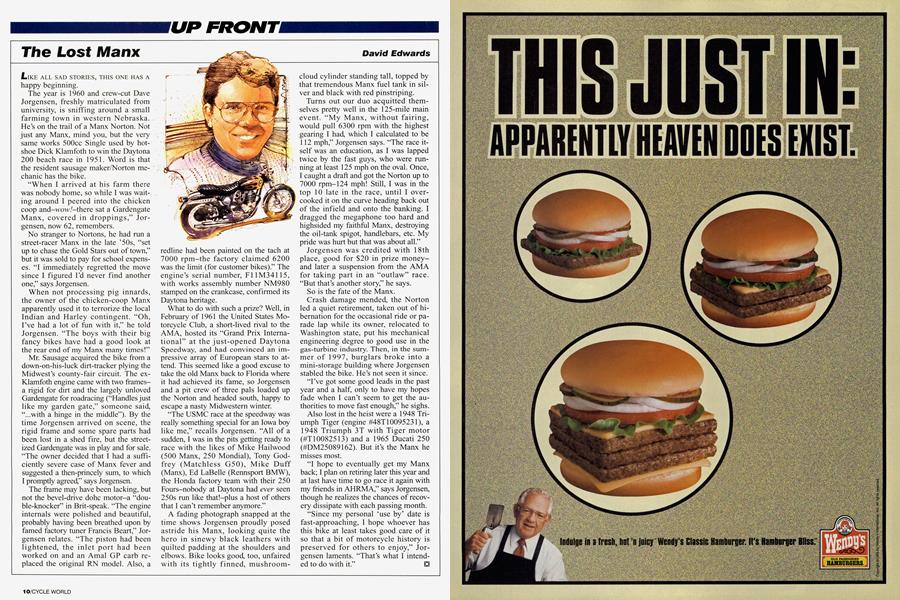

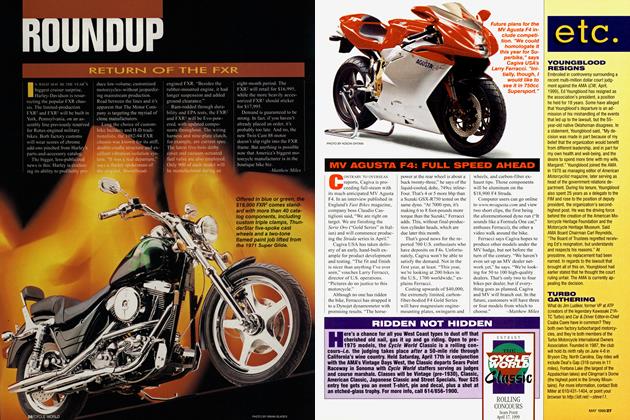

A fading photograph snapped at the time shows Jorgensen proudly posed astride his Manx, looking quite the hero in sinewy black leathers with quilted padding at the shoulders and elbows. Bike looks good, too, unfaired with its tightly finned, mushroomcloud cylinder standing tall, topped by that tremendous Manx fuel tank in silver and black with red pinstriping.

Turns out our duo acquitted themselves pretty well in the 125-mile main event. “My Manx, without fairing, would pull 6300 rpm with the highest gearing I had, which I calculated to be 112 mph,” Jorgensen says. “The race itself was an education, as I was lapped twice by the fast guys, who were running at least 125 mph on the oval. Once, I caught a draft and got the Norton up to 7000 rpm-124 mph! Still, I was in the top 10 late in the race, until I overcooked it on the curve heading back out of the infield and onto the banking. I dragged the megaphone too hard and highsided my faithful Manx, destroying the oil-tank spigot, handlebars, etc. My pride was hurt but that was about all.”

Jorgensen was credited with 18th place, good for $20 in prize moneyand later a suspension from the AMA for taking part in an “outlaw” race. “But that’s another story,” he says.

So is the fate of the Manx.

Crash damage mended, the Norton led a quiet retirement, taken out of hibernation for the occasional ride or parade lap while its owner, relocated to Washington state, put his mechanical engineering degree to good use in the gas-turbine industry. Then, in the summer of 1997, burglars broke into a mini-storage building where Jorgensen stabled the bike. He’s not seen it since.

“I’ve got some good leads in the past year and a half, only to have my hopes fade when I can’t seem to get the authorities to move fast enough,” he sighs.

Also lost in the heist were a 1948 Triumph Tiger (engine #48T 10095231), a 1948 Triumph 3T with Tiger motor (#T 10082513) and a 1965 Ducati 250 (#DM25089162). But it’s the Manx he misses most.

“I hope to eventually get my Manx back; I plan on retiring later this year and at last have time to go race it again with my friends in AHRMA,” says Jorgensen, though he realizes the chances of recovery dissipate with each passing month.

“Since my personal ‘use by’ date is fast-approaching, I hope whoever has this bike at least takes good care of it so that a bit of motorcycle history is preserved for others to enjoy,” Jorgensen laments. “That’s what I intended to do with it.” □