A Higher Calling

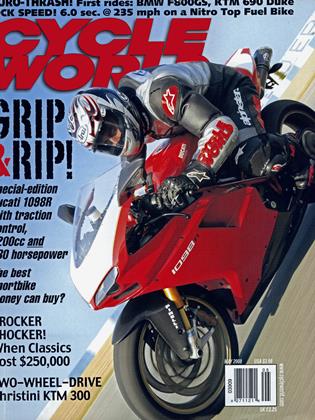

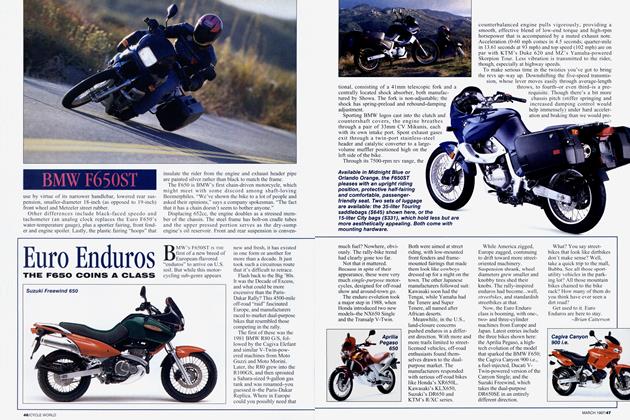

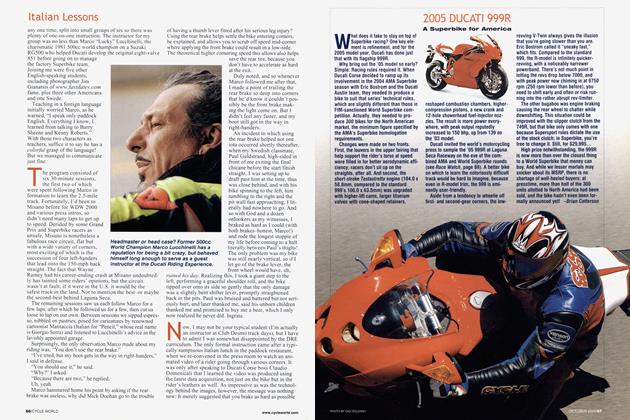

Already Bike of the Year, Ducati’s 1098 gets more displacement, more power, better suspension, better brakes, traction control and a ticket to World Superbike

KEVIN CAMERON

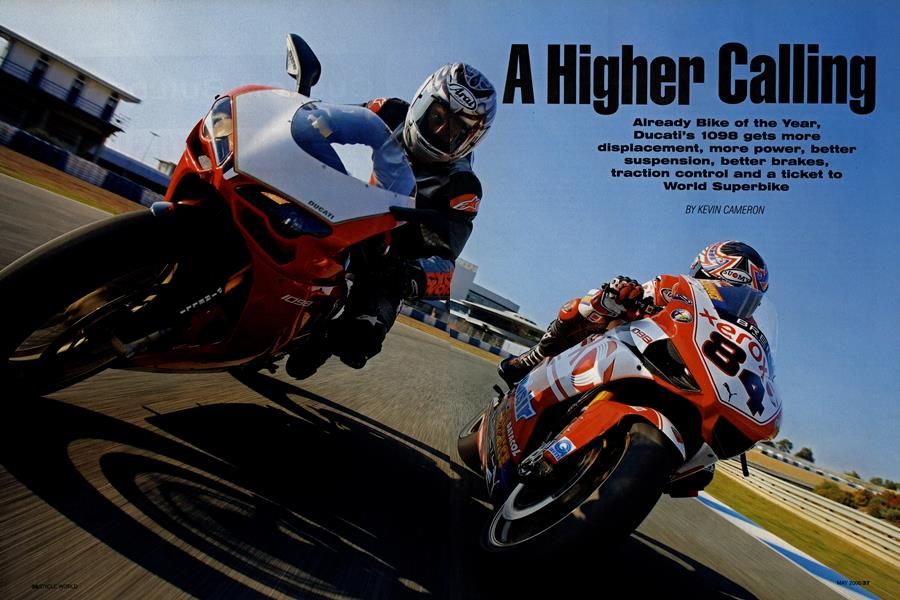

So, WE’VE RIDDEN DUCATI’S new 1098R, the company’s hi-po homologation special for World Supers. But there are ramifications that make it a lot bigger than that. This is the real deal-the electronic motorcycle. While other makers are calling their first-level traction control coy names like “Noodle Twist Prevention System,” Ducati is calling theirs...Ducati Traction Control. Here it is, on the 1098R, and it’s implemented at eight different levels. Each level holds rear tire spin to a certain number of rpm above front wheel speed. Just dial-in the protection you want on the digital race display dash.

Associate Editor Mark Cernicky, with 25 other rider-journalists, spent a full 9-to-5 day at the Spanish Jerez circuit thrashing 11 new 1098Rs-and playing with the DTC system.

The 1098R is the basis model for Ducati’s 2008 World Superbike effort, so it’s not even a 1098 at all. Instead, its whopping 106mm bore and 67.9mm stroke give it 1198.4ccjust nudging the 1200cc limit for Twins under the new WSB regs. Want power? The R makes a claimed 180 hp at 9750 rpm with its normal mufflers, jumping to 186 hp with the 102-dB carbon muffler race exhaust and dedicated ECU. When the rev-limiter cuts in at 10,500 rpm, piston speed is just under 4700 feet per minute. More importantly, peak piston acceleration is a moderate 5000 g-a lot lower than it is on current 600cc sportbikes. Continuing to poke at my trusty, 20-year-old TI-35 calculator, I find that stroke-averaged net combustion pressure at peak power is an impressive 200 psi, rising to 205 psi down at the 7750-rpm torque peak. Those are racing numbers, and that very small drop from 205 to 200 across 2000 rpm suggests very flat torque.

Ramifications? What ramifications? This 1098R either represents the electronic future of motorcycling or-in the view of others-it stands for a pernicious evil that must be stopped. If the electronic motorcycle is the future, then racing series such as World Superbike and MotoGP are the most powerful development tools available to the factories. But forces within racing object that electronics prevent the full expression of rider talent. That, they argue, is the cause of a large drop in MotoGP’s TV appeal in the key markets of Italy and Spain-a fall that racing’s managers cannot ignore. Yet if racing is “purified” of its electronics, its value as a development tool will decline. Will all five manufacturers support that?

Others tie MotoGP’s TV ratings drop to Valentino Rossi’s absence from the podium. He, more than any other force, has made MotoGP what it is. When he could have dominated the sport completely-as Mick Doohan did for five straight years-he instead played cat-and-mouse with opponents like Max Biaggi and Sete Gibemau, making MotoGP fascinating.. .and very popular. Without doubt, he is racing’s Indispensable Man.

When two years ago I asked Dorna President Carmelo Ezpeleta where the sport will go when Rossi leaves it, he could only answer that, “New talents appear.” At this 1098R test, I spoke with Pirelli Racing Manager Giorgio Barbiere about this. He said, “For some time, people have wished for talented younger riders to enter this sport. Now that they are here, and they are so successful, some are wishing they would go back where they came from!” He was speaking of Casey Stoner, Dani Pedrosa, Jorge Lorenzo and the other fast, hot youngsters who are moving up as Rossi seemingly marks time. Maybe the best thing to say at this point is, “That’s racing.” Banning electronics won’t bring back the past or its stars-it will alter only the future.

Why does Ducati need a homologation special for World Superbike? Hasn’t the race team been immensely successful there? Yes, but when Claudio Domenicali was tasked with reversing Ducati’s ailing streetbike fortunes, his first act was to make production Ducatis performance-competitive with all others. In a world of lOOOcc Fours, that called for more displacement, and the successful new 1098 now has it. But to maintain Ducati’s strength in World Superbike and other racing venues, there also had to be an adjustment. The WSB formula used to be lOOOcc Twins versus 750cc Fours, with the displacement difference compensating for the higher rev capability of the Fours. But when lOOOcc Fours became top sellers for Japanese makers, a new deal was cut in 2003, with displacement set at lOOOcc for both Twins and Fours. To maintain parity, Fours were limited to use of many stock internal parts and stock-weight valves, while Twins were permitted a much higher (but quite expensive) state of tune. For ’08, Ducati proposed that Twins be given a 1200cc limit but subject to the same reduced engine-tune level as for four-cylinders. This has been adopted, and the 1098R is the homologation basis for the new racing 1200.

Ducati marketing skills are sharp. The company has only to announce a tasty new model on the Internet (provided styling is right) and it is flooded with orders. Bologna knows just how many people might be willing to pay how much (in this case, $39,995) for which degree of two-wheel beauty and sophistication.

The R has higher-strength sandcast heads and crankcases in place of the mass-produced diecast 1098 items. Dwelling within are oversize titanium valves (44.3mm inlets vs. previous 42; and 36.2mm exhaust vs. 34), a lightweight crankshaft machined on all surfaces and counterweighted with six tungsten slugs (density of tungsten is 18 vs. 7.8 for steel), and a gearbox with special ratios. The engine’s size and compression ratio require a special, lower-ratio starter gear to crank over. Connecting rods are 325-gram titanium forgings (29 percent lighter than stock 1098) from Austrian maker Pankl, and pistons are the usual nine-cavity forgings done in the veteran RR58 aluminum. Their domes are very smooth, with no sharp edges or bumps to interfere with fuelair charge motion at the tight squeeze of a 12.8:1 compression ratio (stock is already high at 12.5:1).

Everyone riding this bike spoke of its massive torque, and its source is right here-high compression, a fast-burning combustion chamber and good breathing not dependent upon long valve timings. Riders also spoke of little overrev-the engine pulls hard straight into its rev-limiter. With pistons and valves this big, the rods and valve-operating levers need protection from rider enthusiasm.

To operate those big valves, cam levers have been changed from stock chrome-plating on wear surfaces to a “superfinish” process. The aim is to raise the fatigue limit of these critical parts, which in turn raises the safe maximum acceleration that can be applied to the valves.

Fitted as standard is a wet, backtorque-limiting, or slipper, clutch.

When you close the throttle of a largedisplacement motorcycle at speed, the rear tire must drive the engine, whose internal friction amounts to many horsepower. The resulting friction torque, applied to the rear tire, can make it hop or slide when straight up, and can cause it to slide out unpredictably as the machine leans over into a turn. A slipper clutch uses that reverse torque to reduce spring pressure on the friction-plate stack, allowing the clutch to slip rather than cause mischief at the back tire. It’s fast becoming a requirement of frontline sportbikes, if only at the insistence of the brochure scribblers.

Ducati’s trademark trellis chassis gives steering geometry of 24.5 degrees rake and 3.8 inches trail, with a wheelbase of 56.3 inches. Weight is a claimed 363 pounds, 13 lighter than a stock 1098. As this machine is a single-seater, the bolted-on tubular rear subframe is aluminum rather than steel, saving nearly 3 pounds. Many other small details-such as carbon-fiber belt covers-helped with the weight savings.

Looking closely at the machine, you see front and rear wheel-speed sensors in place, the front one triggering off the passage of the six brake-disc floater buttons, the rear reading pins riveted into the disc. Front discs are very large-330mm Brembos-and calipers are four-piston Brembo Monob/occos with the red lettering so long seen on roadrace start grids. Their blind piston bores are mysteriously machined by a boring head that acts from within the pad space. Cernicky thought the brakes looked a bit much at first, but when he began to hot lap he soon realized they were, in fact, a necessity-that big engine throws a lot of energy into those discs!

Wheels are gold-finished Marchesini forged aluminum, their five Y-spokes each machined to shape. A bulky black single-sided swingarm-part of Ducati’s “recovery” from the too-conventional 999-is welded from sheet and cast components. Up front, gold-on-gold 43mm Öhlins fork legs are held by a stiff hollow-box cast lower crown with two pinch bolts per side, and a billet plate top crown, anodized black. A projection from the top crown drives the transverse-mounted steering damper behind the headstock axis.

Just under the rider’s hands on each side is an air duct. Twin intakes in the fairing front feed the big airbox atop the engine. Also in the nose are side-by-side twin projector “Motorcycle DOT SAE” headlights.

Rear suspension is via one of Öhlins’ formerly racing-only TTX36 units. Previous dampers have placed the rebound valving on the piston and the compression stack in the line to the pressure accumulator. That flow arrangement meant that pressure from the accumulator-which exists to prevent cavitation and resulting erratic motion-had to flow back through the compression valve, into the working cylinder and through the damper piston to reach the last chamber. The “TT” stands for Twin Tube, a new construction in which the piston is solid. The “36” refers to damper piston diameter. As the piston moves on compression, it pushes fluid from the inner cylinder, through the compression valve stack and into the concentric outer cylinder. On rebound, the piston pushes fluid behind it, into the outer cylinder, through the rebound stack and back into the other end of the inner cylinder. Pressure from the accumulator has direct access to both sides of the piston, making suppression of cavitation much more effective. This allows accumulator pressure-previously 175 psi-to be cut to 90 psi, thus usefully reducing shaft-seal stiction. Both valve stacks are screwed into the base of the damper body side-by-side, with the 20-position clickers above them (formerly, the rebound clicker was on the end of the damper rod, and the compression clicker next to the accumulator.)

TTX construction makes valve re-stacking, which used to require complete disassembly, much easier. With TTX, you depressurize, orient the body with valve hexes uppermost, then simply unscrew and remove the valve stacks, leaving the damper full of oil. It is also claimed that the greater consistency of the TTX reduces the frequency of shock maintenance.

Rider experience associates racing suspension with the harshness of stiff springs and their partner, heavy damping. But when damping is made more consistent, peak forces are reduced. Test riders at Jerez were calling the 1098R’s suspension “plush”-and so it should be. To keep tires in contact with the pavement, suspension has to move easily.

Parked outside the red-carpeted garage at Jerez was a machine equipped with many parts from Ducati Performance-bulky Superbike swingarm, remote brake-lever-height adjuster, breakaway foot and hand controls—all tasty, visible treats. There is always more if you want it. Back in the 1920s, Alfred P. Sloan at GM showed that if you offered a stairway of progressively more expensive and attractive models, customers would make every effort to climb it. That is even more true today.

Ducati set out engine parts for us to see-head, crankshaft, piston, con-rod, ring set, and intake and exhaust valves.

A permanent concern has been to push the long engine as far forward as possible, for the 90-degree Vee construction places the heavy crankcase and rear cylinder far back. A part of achieving this is to make the exhaust valves 10mm shorter than the intakes, and to tilt the parting line of the cam cover at about 13 degrees. This allows the engine to come forward by that 10mm (.4-inch), putting the front cylinder’s cam cover very close to the front tire during hard braking.

Looking rearward, it’s instructive to compare this machine’s swingarm length (193/s inches) with those of its competitors, the Japanese transverse Fours, which are generally 23(4 inches. Ducati has dealt with its rearward weight bias every way it can. The battery, for example, is carried forward on the left side of the front cylinder. Now consider how torque characteristics are an integral part of handling. As you accelerate, with less excess weight margin on the front than your competition, you must deliver torque so smoothly that the front tire is not jerked upward by any bumps in the torque curve. This keeps the front end steering.

How do you smooth engine torque? The new way is throttle-by-wire, in which torque maps keep the throttle butterflies fluttering, filling in the dips, planing off the bumps and staying hooked-up. But that’s MotoGP’s way. For production bikes like this R-model-at least for the moment-the answer is what it was in MotoGP through 2003: a passively smoothed engine torque curve. Light valves and fatigueresistant rockers are how you make “square” cams and short valve timing possible and reliable, the tools that generate flat, usable torque. Everything-and I mean everything-is interrelated on a motorcycle.

Vehicle technologies are changing so fast right now that every problem is a moving target, under attack from multiple directions. Can traction control mask a rough powerband? Probably not quite. But in MotoGP, throttle-by-wire can.

And there’s no arguing that TBW isn’t coming to sportbike showrooms, that it’s too expensive, too exotic. It’s already here, on Yamaha’s YZF-R6 and Rl. Who’ll be next? Oh, but racing is too specialized. Oh yeah? I heard Ducati engineer Andrea Fomi clearly state that the 1098R’s traction-control algorithm is 100 percent identical to that used in MotoGP and WSB. He also said that race spec and production have never been so close as now.

This is the beauty of the motorcycle, as compared with the automobile. Auto racing has moved so far from production that it has become a completely separate business with its own manufacturers. Motorcycle racing, on the other hand, is conducted by motorcycle manufacturers precisely because the relationship between production and racing is so close. If that relationship is cut by an electronics ban, it will be interesting to see how motorcycle racing fares on its own.

There was talk at Jerez of a potential .6-second drop in lap times with Ducati Traction Control, and riders enjoyed their close encounter with it. In a very short time, such technologies will be ordinary and necessary, just as electronic fuelinjection is now. In this 1098R track test, 26 magazine guys did hundreds of laps on a machine whose power-to-weight ratio is 35 percent higher than that of the fabled Yamaha TZ750 (2 lb./hp for the 1098R; 2.7 for the TZ). In all those laps, there was only one fall, a cold-tire mistake without injury. That impresses me very much. What it means is that motorcycle technologies have advanced to the point that experienced but otherwise ordinary riders can control and use power of this kind. Electronic fuel-injection is smooth. Modern suspension is consistent. Now Ducati Traction Control joins the list of reasons such a fabulous machine can be so controllable.