THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WORLD, THE WRONG SIDE OF THE ROAD.

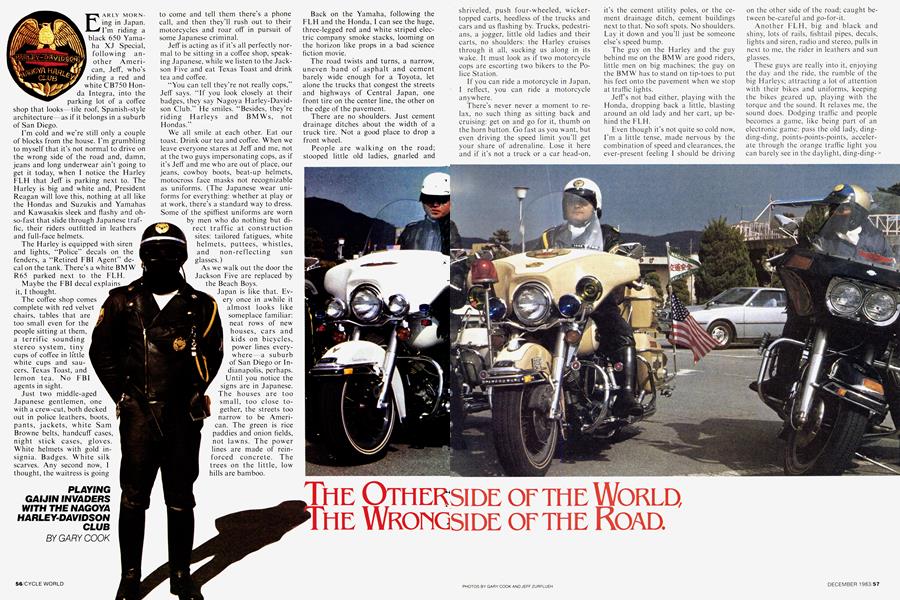

PLAYING GAIJIN INVADERS WITH THE NAGOYA HARLEY-DAVIDSON CLUB

GARY COOK

EARLY MORNing in Japan. I'm riding a black 650 Yamaha XJ Special, following another American, Jeff, who's riding a red and white CB750 Honda Integra, into the parking lot of a coffee shop that looks—tile roof, Spanish-style architecture—as if it belongs in a suburb of San Diego.

I’m cold and we’re still only a couple of blocks from the house. I'm grumbling to myself that it’s not normal to drive on the wrong side of the road and, damn, jeans and long underwear ain’t going to get it today, when I notice the Harley FLH that Jeff is parking next to. The Harley is big and white and, President Reagan will love this, nothing at all like the Hondas and Suzukis and Yamahas and Kawasakis sleek and flashy and ohso-fast that slide through Japanese traffic, their riders outfitted in leathers and full-face helmets.

The Harley is equipped with siren and lights, “Police” decals on the fenders, a “Retired FBI Agent” decal on the tank. There’s a white BMW R65 parked next to the FLH Maybe the FBI decal explains it, I thought.

The coffee shop comes complete with red velvet chairs, tables that are too small even for the people sitting at them, a terrific sounding stereo system, tiny cups of coffee in little white cups and saucers, Texas Toast, and lemon tea. No FBI agents in sight.

Just two middle-aged Japanese gentlemen, one with a crew-cut, both decked out in police leathers, boots, pants, jackets, white Sam Browne belts, handcuff cases, night stick cases, gloves.

White helmets with gold insignia. Badges. White silk scarves. Any second now, I thought, the waitress is going to come and tell them there’s a phone call, and then they’ll rush out to their motorcycles and roar off in pursuit of some Japanese criminal.

Jeff is acting as if it’s all perfectly normal to be sitting in a coffee shop, speaking Japanese, while we listen to the Jackson Five and eat Texas Toast and drink tea and coffee.

“You can tell they’re not really cops,” Jeff says. “If you look closely at their badges, they say Nagoya Harley-Davidson Club.” He smiles. “Besides, they’re riding Harleys and BMWs, not Hondas.”

We all smile at each other. Eat our toast. Drink our tea and coffee. When we leave everyone stares at Jeff and me, not at the two guys impersonating cops, as if it’s Jeff and me who are out of place, our jeans, cowboy boots, beat-up helmets, motocross face masks not recognizable as uniforms. (The Japanese wear uniforms for everything: whether at play or at work, there’s a standard way to dress. Some of the spiffiest uniforms are worn

spiffiest are worn by men who do nothing but direct traffic at construction sites: tailored fatigues, white helmets, puttees, whistles, and non-reflecting sun glasses.)

As we walk out the door the Jackson Live are replaced by the Beach Boys.

Japan is like that. Every once in awhile it almost looks like someplace familiar: neat rows of new houses, cars and kids on bicycles, power lines everywhere—a suburb of San Diego or Indianapolis, perhaps. Until you notice the signs are in Japanese. The houses are too small, too close together, the streets too narrow to be American. The green is rice paddies and onion fields, not lawns. The power lines are made of reinforced concrete. The trees on the little, low hills are bamboo.

Back on the Yamaha, following the FLH and the Honda, I can see the huge, three-legged red and white striped electric company smoke stacks, looming on the horizon like props in a bad science fiction movie.

The road twists and turns, a narrow, uneven band of asphalt and cement barely wide enough for a Toyota, let alone the trucks that congest the streets and highways of Central Japan, one front tire on the center line, the other on the edge of the pavement.

There are no shoulders. Just cement drainage ditches about the width of a truck tire. Not a good place to drop a front wheel.

People are walking on the road; stooped little old ladies, gnarled and shriveled, push four-wheeled, wickertopped carts, heedless of the trucks and cars and us flashing by. Trucks, pedestrians, a jogger, little old ladies and their carts, no shoulders: the Harley cruises through it all, sucking us along in its wake. It must look as if two motorcycle cops are escorting two bikers to the Police Station.

If you can ride a motorcycle in Japan, I reflect, you can ride a motorcycle anywhere.

There’s never never a moment to relax, no such thing as sitting back and cruising: get on and go for it, thumb on the horn button. Go fast as you want, but even driving the speed limit you'll get your share of adrenaline. Lose it here and if it’s not a truck or a car head-on, it’s the cement utility poles, or the cement drainage ditch, cement buildings next to that. No soft spots. No shoulders. Lay it down and you’ll just be someone else’s speed bump.

The guy on the Harley and the guy behind me on the BMW are good riders, little men on big machines; the guy on the BMW has to stand on tip-toes to put his feet onto the pavement when we stop at traffic lights.

Jeffs not bad either, playing with the Honda, dropping back a little, blasting around an old lady and her cart, up behind the FLH.

Even though it’s not quite so cold now, I’m a little tense, made nervous by the combination of speed and clearances, the ever-present feeling I should be driving on the other side of the road; caught between be-careful and go-for-it.

Another FEH, big and black and shiny, lots of rails, fishtail pipes, decals, lights and siren, radio and stereo, pulls in next to me, the rider in leathers and sun glasses.

These guys are really into it, enjoying the day and the ride, the rumble of the big Harleys; attracting a lot of attention with their bikes and uniforms, keeping the bikes geared up, playing with the torque and the sound. It relaxes me, the sound does. Dodging traffic and people becomes a game, like being part of an electronic game: pass the old lady, dingding-ding, points-points-points, accelerate through the orange traffic light you can barely see in the daylight, ding-ding-> ding, points-points, ahead of that truck, into the slot behind Jeff, points. Beep your horn at the idiot coming half out of a blind side street before he stops and looks, ding-dirtg-ding, points-points, he stopped, accelerate to catch Jeff, losing time, you’re losing time, open it up a little, the shaft drive smooth, the Yamaha about four times as quick as the heavy FLH, points-points, light is turning red, stop-stop, subtract points, ding-dingding, Jeff has made it through. Damn. Big black FLH, white BMW behind you, two pairs of sun glasses staring at you in the mirrors, accusing: Why’d you miss that light, boy? Light turns color and the Toyota Turbo Something on the right jumps ahead, subtract more points, dingding, black FLH passing on the left. Damn, boy, open that sucker up. And the Yamaha hits about 5500 rpm and, extrapoints, extra-points, goes into hyperspace and you’re, points-points, blasting past the FLH and the Turbo Toyota Something, ding-ding-ding, pointspoints, dodging around a car turning right and, damn, subtract points, subtract lots of points, as you narrowly miss a red car sliding across into your lane forcing you to hit the brakes, back and front, and downshift, tires squeaking, back end coming around a little. You dummy. Lose lots of points for poor driving ability, lose even more points because you just scared yourself.

“Was that you I heard back there?” Jeff says at the next light, disgust in his voice.

“Uh . . . well. I think the back tire needs air, or something.”

Jeff laughs.

The Yamaha really is a nice bike, even if it doesn’t appreciate me driving it.

Plenty of power, smooth, comfortable, but probab a sport bike like Jeff’s is more suited to this kind of traffic. Driving the big FLHs in these conditions must be like running in snowshoes, but we’ve picked up three or four more of them and nobody seems to be having any problems.

We’re riding in formation, now, Jeff and me toward the back so I can watch everything. Because they are dressed like cops, and because so many people take them for cops, the Club members are riding in an exemplary manner, considering themselves, looking as they do, representatives of law and order, trying to leave a good impression, set an example.

We’re supposed to rendezvous with the other Club members at a rest area on the expressway. The expressway reminds me of an Interstate in the States; the traffic is sparse, there’re even shoulders on the road, but the Harleys stay at an even 80 kph, the speed limit.

At the toll booth, spiffy in his tailored uniform, the man is rude to the Club members and to Jeff and me, irritated at the time it takes Jeff to pull his glove off and give him the required amount of yen. (Normally, Japanese are extremely polite and helpful to foreigners, sometimes infuriatingly so, but the man at the toll booth is definitely on some kind of power trip, secure in his niche in the bureaucracy.) Most of the Club members have their money ready; the black FLH even has a coin changer mounted on the fairing.

The rest stop is full of cars and trucks. The bathrooms are clean, the coffee dispenser actually works and there’s no graffitti on the walls. People are more curious about Jeff and me than they are about the Harley Club members and their uniforms and bikes.

“Are you American?” one man shyly asks.

“Yup.”

“How tall are you?”

“ ’Bout six feet three inches.”

The man huddles in serious discussion with three or four uniformed Club members, trying to convert the feet and inches ‘ to meters and centimeters. Suddenly they all look up at me, their eyes round with surprise.

“So tall ... ,” the man says. (Once upon atime, for six or seven years, there were a lot of Americans, soldiers mostly, in this part of Japan, but today, with the exception of the Tokyo and Osaka areas, Americans are relatively scarce, two of them on motorcycles scarcer still. The small, shy man turns out to be a doctor who is also a Harley Club member, but today he is following the Club in a station wagon with his family. He’s middleaged, like most of the Club members, and he likes collecting Harleys and jeeps because he remembers when he was a kid staring through the wire at the Americans in the American Military compound, their size, their lifestyle, staring at their cars and jeeps and jeeps and jeeps and big Dodge personnel carriers.

“Japan was so poor,” he says. “We had to work so hard.”

Today, like most of Japan, and all of the Harley Club members, he has succeeded in acquiring that life style, and more. But it makes me pause to think of this small, shy man, a little boy peering through the wire at the big, powerful, rich Americans, our fathers and uncles in the Occupation Forces—a small, hungry boy saying to himself, I’m goin to get me some of that.

Suddenly the rest area is full of FLH’s, a long line of them, two abreast, coming into the parking lot off the expressway, dull sheen of good leathers, white helmets and dark sun glasses, and the Harleys themselves, chrome glinting in the hard winter light, the heavy rumble unmistakably Harley-Davidson. I couldn’t help thinking that the sight would have done Reagan’s heart good. It costs the average Harley Club member a little over $12,000 just for the basic motorcycle, another $4000 for the bike inspection, extras for the bike, leathers and police equipment. There are 50,000 Harleys in Japan, at least 10,000 of them FLH’s, many of them less than five years old. Not only were these Harley-Davidson motorcycles pulling into the rest area being ridden by Japanese in Japan, but the Japanese riding them were wearing uniforms, and they like wearing uniforms; they like being organized and, uhhh, you ought to look at these guys, Mr. Reagan, sir, because, no doubt about it they’d make terrific soldiers and fighters. (There were other little kids looking at the Americans through the wire, and some of them were looking at more than just big cars and people). Before we persuade them to take a more active part in the defense of South East Asia and thus the West, perhaps you ought to come over here and have a look at this here Harley-Davidson Club, and at all the University Student Clubs. All are populated by students who say they never want to see Japan fight a war again, but who nevertheless, men and women, do everything organized and in cadence and with a terrific amount of group aggression and fighting spirit. Sort of like the Marines I went to Vietnam with.

For sure it takes a certain kind of individualism to walk out of your house in the morning dressed almost exactly like a Japanese motorcycle cop, jump on an FLH and roar off through the neighborhood, down to the local coffee shop, and meet a bunch of other similarly dressed and motorcycled men, most of whom in real life are government workers, doctors, dentists, or businessmen who own their own businesses.

It also takes a certain amount of courage: one guy showed up after the ride, in civilian clothes, on his FLH, and apologized because he couldn’t make the ride, but finally admitted that his wife was really embarrassed everytime he walked out of the house dressed like a cop, implying that she raised hell, in one way or another, everytime he1 rode with the Club.

Back out onto the expressway, following about 20 FLHs (there are nearly 50 in the Nagoya Club), Jeff on a Honda, me on the Yamaha, nobody was worrying much about their wives: a long line of cops on big, fat Harleys, lots of chrome and bags, decals, lights, flags, two abreast, cruising at 80 kph. A car passed, kids gaping, and Jeff waved at the kids, and I saw one of them mouth the word gaijin, foreigner, foreigner, and everyone in the car, including the driver turned to look at Jeff and me.

We were on the expressway for only 20 min. or so. As we turned off I mentally prepared myself for reentry back into the electronic game, Gaijin Invaders dodging, swerving, accelerating through the press and confusion of cars, trucks, bicycles, pedestrians, old ladies, narrow roads, traffic signals that are difficult to see in the daylight. But this time riding with the Harley Club there’s none of that, just a sedate and ponderous ride onto a secondary highway, four lanes, the mass of big motorcycles rumbling through the traffic, like an icebreaker through ice, the Club members riding very military, exuding an air of pride and competence that made it difficult for me to believe these people follow other, more normal pursuits in daily life.

The ride began to be a bit tedious: years spent in the Marines, and as a cop, have left me with a low tolerance for things military. I was getting bored and I could see Jeff was too, wanting to open the Honda up a little, get to the front of the traffic where it’s safer and play with the other sport bikes, and with the occasional Porsche, Jaguar, or Mercedes. (It’s rare to see a bike over 750cc in Japan; larger than 750cc and, Japanesemade or not, the motorcycle must be exported and imported, thus requiring payment of the import tax on motorcycles.)

There’s a silver Mercedes in the lane next to us, and it’s being driven by an exotic looking creature. Probably her father’s car, I figure. But there’s a lot of money in Japan these days and you can never tell.

She’s trying to ignore all these cops on Harleys and hasn’t noticed that my black Yamaha and cowboy boots and jeans, blue motocross mask and scratched and pitted helmet are most un-Japanese. (Who knows, maybe she’ll think I’m as exotic as I think she is; maybe she’ll think my clothes are eccentric and dashing in a gaijin sort of way.)

All but the front two bikes have been forced to stop at a stoplight, and for some reason, sitting at the stoplight, I look away from the Mercedes, just as the two FLH’s that have gone through the light collide with each other. The sudden impact generates a nasty amount of torque, the two motorcycles warping upward together, and both bikes are down, one of them spinning and twisting across the pavement, red plastic scattering, the other bike on its side, both men on the pavement.

There’s a pause, a sort of collective, Oh, no, I didn’t really see that, and then several of the front bikes and Jeff’s Honda roar forward through the light which luckily is at the junction of a T and has no cross traffic.

The accident is only about 75 meters away^ but before they get there, one man is up and, even from that distance, the one who is still down doesn’t look badly hurt. The helmet and leathers, boots, gloves, and crash bars on the bikes have kept the damage, human and mechanical, to a minimum: a bruised arm, a broken tail light and a bent and loose exhaust pipe.

But the loss of face, expecially with two American gaijin along, has threatened to ruin the day’s ride, and 15 min. later, after the pieces have been picked up and we’re again on our way, the atmosphere is tense, the easy confidence and pride replaced by embarrassment and self-consciousness.

The Mercedes and the girl are long gone.

When it happens, as it does sooner or later to most of us, it’s usually because we were being careless or over-confident, relaxed when we should have been alert. When the lead bike saw everyone else stopped at the light, he slowed, and the bike behind, who was also watching his mirror, ran into the front bike and both went down. Could have been bad, could have been avoided; it was neither, but it was one of those things you’d give anything to take back.

The Japanese have a wonderfully fatalistic word for such occasions: shogennai, there’s nothing to be done about it.

The kaicho, the boss, decided, out of consideration for the wounded—men or machines, I wasn’t sure which—to cut the ride short. An alternate route was decided upon, morale low as the big Harleys turned off onto smaller roads and, single-file, threaded through traffic, the Club members no longer playing with the sound of their Harleys, just riding smooth and efficiently, the rider who was slow getting up off the pavement nursing his arm.

Two of the bikes were riding several blocks ahead directing the group, like two motorcycle cops at a parade clearing traffic, keeping the crowd back. They were showing off a bit, creasing in and out of traffic, letting us know that at least some of them can handle the big Harleys as well as any gaijin.

At an intersection they are obviously lost, one of the bikes riding back and forth across the intersection in front of us, uncertain which fork to take, making everyone laugh,hamming it up,; back and forth, back and forth, acting like the epitome of a stubborn and officious motorcycle cop trying to look like he knows what he’s doing, even though everyone knows he doesn’t. The guy makes a few more passes, aware that his antics are raising morale, and it’s refreshing to realize that the Japanese also love to poke fun at that certain mentality, that 10 percent of officialdom everywhere, whether it be motorcycle cops or rude and uniformed men at toll booths on the expressway.

The restaurant is on the second floor of a hotel next to the ocean, bowling alley on the ground floor, and I hit my head going through the bathroom door, putting a welt on my forehead, cursing that doors in Japan are designed by people who must feel most at home in a submarine.

Lunch is greasy spaghetti, and the coffee is one dinky little white cup half-full (Japanese feel it’s not polite to fill a cup or glass). Nevertheless, the coffee helps warm me.

But later, back on the Yamaha, headed home, the combination of cold and caffeine makes me want to stop for a few minutes. (Occasionally in Japan someone will stop his car in the middle of the road, bringing traffic behind to a halt, jump out, and without any apparent show of modesty, irrigate the rice paddy.) About the time I’m seriously considering the idea, however, the Harley Club pulls into the parking lot of another restaurant where, as I hop from one foot to the other, Jeff insists on having his picture taken.

The restaurant is one of a chain called Meadowlark, modeled after Denny’s (there are Denny’s in Japan, too. Lots of them. Just like in the States. Another one of those sights in Japan that makes you feel as if you’re caught in some warp halfway between America and Asia, in a story that ought to be narrated by Dan Ackroyd mimicking Rod Serling.) The bathroom, the tables and chairs, the red carpet, the whole place is pure Anywhere America.

“What do people think of you,” I asked one of the Harley Club members, “when they see you dressed like cops, riding huge, American motorcycles?”

“The older people think we're crazy, but the younger people think it’s terrific.”

Another member

walked by our table, and I asked him if he was really carrying handcuffs and nightstick and, sure enough, high-quality handcuffs exactly like the real cops carry, and a kind of thin, telescoping night stick that has a hard little ball on the tip.

“You could kill someone with that,” I said. “Poke them in the wrong place.”

“No. No,” he laughed. “Will collapse hit something,” and just to prove it, he brought down the stick point first, like sticking a knife into something, onto the wooden table top, and left a dent about a quarter of an inch deep. The stick didn’t collapse. He looked at it, bemused: Smiled. Shrugged, Laughed, and went back to his table, struggling to make the night stick collapse.

It reminded me of skiing at a Japanese ski resort. By the end of a day, the trails were reduced to patches of ice and rock and mud, but people were still trying to ski, falling down in the mud, flying off trails into trees, all of which was hilarious to the other skiers.

The point is, Japanese people, most of them, only have the opportunity to ski and vacation once or twice a year; a sixday work week or school to look forward to the rest of the year. And even though this was a poor year for snow, they were damn well going to enjoy their skiing, snow or not.

And that kind of get-into-it, it’s-allyou’ve-got, attitude is very much the attitude that the Nagoya Harley Club members have—the uniforms, the bikes, the once-a-month ride.

As we left the Meadowlark restaurant and headed home on the last leg of the trip, you could see some of the Club members riding not so erect or proud now, losing some of that intensity; just motoring along aware of the cold, beginning to think of homes and businesses, work and families, a little tired but prolonging the once-a-month experience, savoring the last of it.

Put one of them on a Harley, I thought, fill the saddle bags with food and drink, and turn him loose on the Interstate between Seattle and Montana, just him and his machine motoring along: days not minutes to himself; something to look at besides grey buildings and roads and more grey buildings and roads filled with people and cars and trucks, motorcycles, bicycles, little old ladies. He’d be unable to cope with the freedom and exhilaration of being one man on a machine, in a world so big and yet so small. In America the highway stretches ahead, the wide shoulders on the Interstate sloping down into wheat and hay fields, hills and mountains and lakes, cities and towns, clumps of buildings with unlikely names and even more unlikely people.

Five of us—the black FLH, the FLH and BMW we’d met at the coffeehouse in the morning, Jeff and me—peeled off from the main pack and headed home, waving as we left.

A little further on, the black FLH split off. Five must have been the magic number because, abruptly, like pulling into morning rush hour traffic on the freeway, we were back into the Gaijin Invaders game. This time the front FLH, the guy who'd been driving back and forth at the intersection, was in on it, pushing the FLH around corners, choosing narrow narrow roads three or four feet above rice paddies, between clusters of grey buildings, scraping the exhaust pipes on the curves, sparks flying. Jeff’s red and white Honda ripped past me, the BMW in hot pursuit—What’chu waitin’ for boyl—the uniforms and leathers and helmets, the big Harley and BMW incongruous as the rice paddies.

Waitin’ for, I thought, feeling the Yamaha kick in, adrenaline sudden and like carbonation in my blood, What do you think I’m waiting for? I’m waiting for a piece of that Interstate between Seattle and wherever I decide to stop in Montana.

But long as I’m here, I reckon I’ll just—points-points—pass that gnarled and stooped old lady, and—extrapoints— pass the BMW —Get a

Yamaha, sucker—and, careful now, don’t scare yourself—climb right up behind Jeff-san and beep my horn—move over, muh-man, cornin’ through—up behind the Harley, not passing, but staying just close enough so even in the curves he can see me in his mirrors. In my mirrors I can see the Honda sleek and flashy and oh-so-fast, effortlessly taking the corners, the BMW close behind the Honda. Reagan’s dream: a BMW, a Honda and a Yamaha following a Harley. Riding on the other side of the world, on the wrong side of the road. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

December 1983 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

December 1983 -

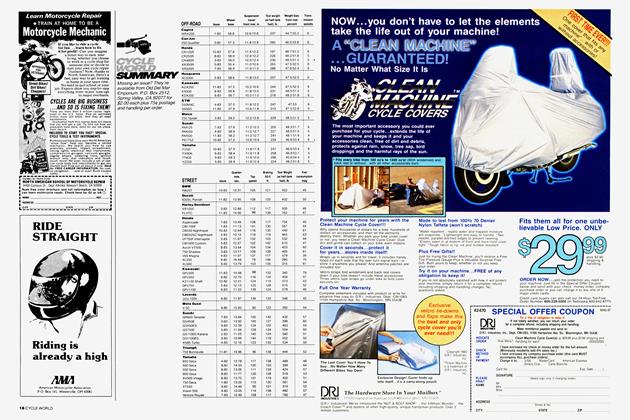

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

December 1983 -

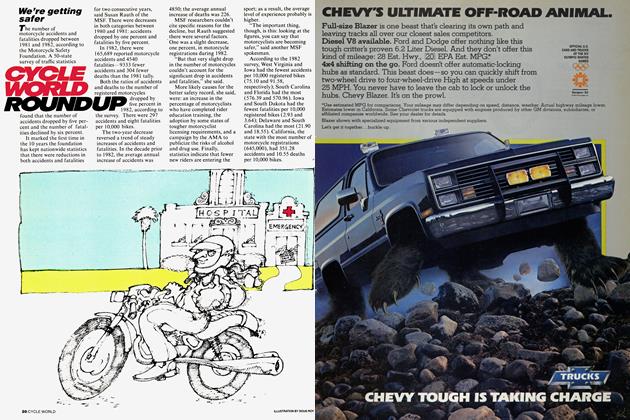

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

December 1983 -

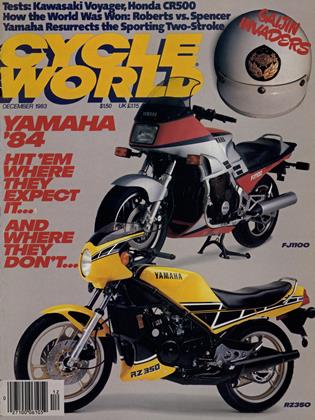

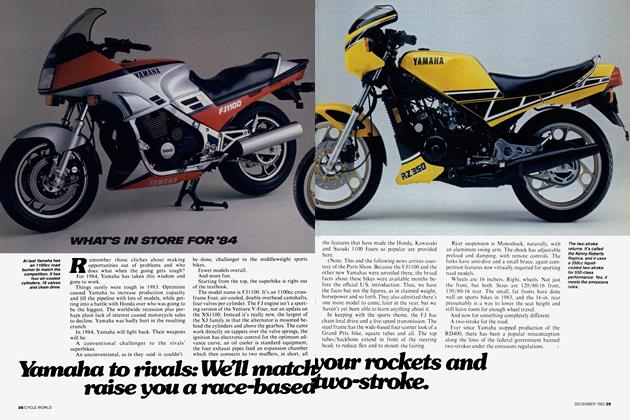

What's In Store For '84

What's In Store For '84Yamaha To Rivals: We'll Match Your Rockets And Raise You A Race-Based Two-Stroke.

December 1983 -

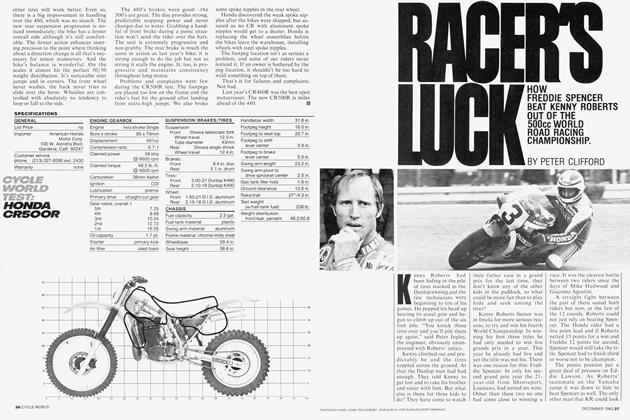

Competition

CompetitionRacer's Luck

December 1983 By Peter Clifford