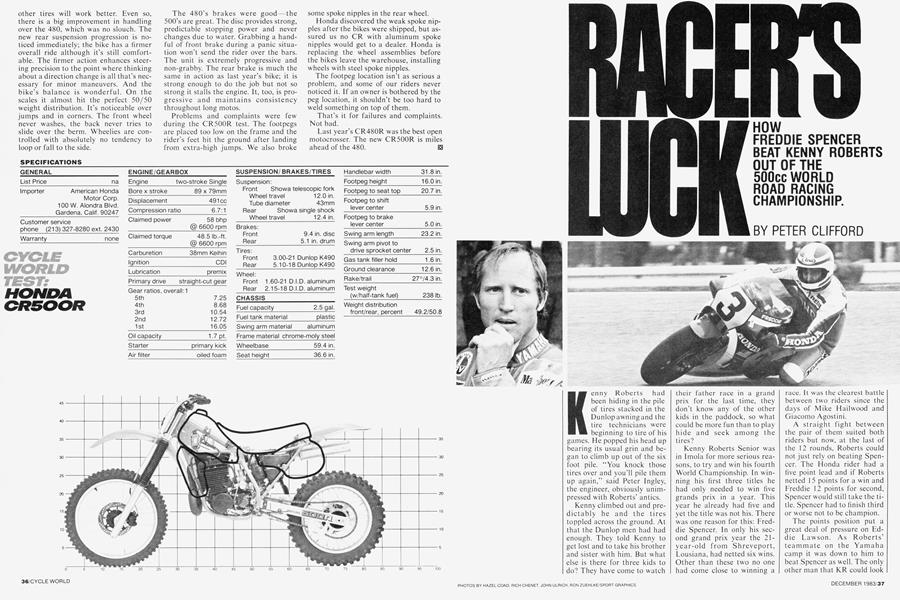

RACER'S LUCK

HOW FREDDIE SPENCER BEAT KENNY ROBERTS OUT OF THE 500cc WORLD ROAD RACING CHAMPIONSHIP.

PETER CLIFFORD

Kenny Roberts had been hiding in the pile of tires stacked in the Dunlop awning and the tire technicians were beginning to tire of his games. He popped his head up bearing its usual grin and began to climb up out of the six foot pile. "You knock those tires over and you'll pile them up again," said Peter Ingley, the engineer, obviously unimpressed with Roberts' antics.

Kenny climbed out and predictably he and the tires toppled across the ground. At that the Dunlop men had had enough. They told Kenny to get lost and to take his brother and sister with him. But what else is there for three kids to do? They have come to watch their father race in a grand prix for the last time, they don’t know any of the other kids in the paddock, so what could be more fun than to play hide and seek among the tires?

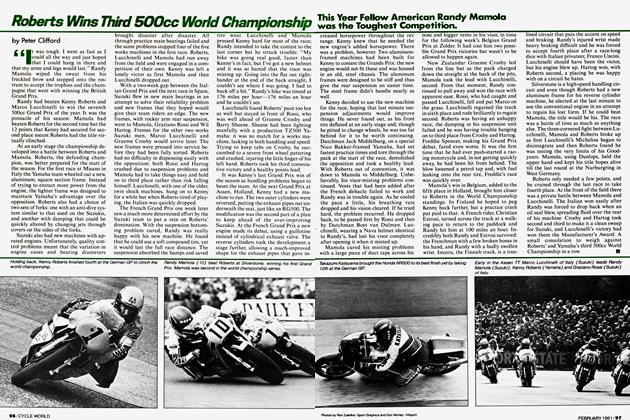

Kenny Roberts Senior was in Imola for more serious reasons, to try and win his fourth World Championship. In winning his first three titles he had only needed to win five grands prix in a year. This year he already had five and yet the title was not his. There was one reason for this: Freddie Spencer. In only his second grand prix year the 21year-old from Shreveport, Lousiana, had netted six wins. Other than these two no one had come close to winning a race. It was the clearest battle between two riders since the days of Mike Hailwood and Giacomo Agostini.

A straight fight between the pair of them suited both riders but now, at the last of the 12 rounds, Roberts could not just rely on beating Spencer. The Honda rider had a five point lead and if Roberts netted 15 points for a win and Freddie 12 points for second, Spencer would still take the title. Spencer had to finish third or worse not to be champion.

The points position put a great deal of pressure on Eddie Lawson. As Roberts’ teammate on the Yamaha camp it was down to him to beat Spencer as well. The only other man that KR could look on for help was Randy Mamola. Randy had been riding the H.B. Suzuki hard all year, but neither its engine nor frame had been up to the task and it would have been optimistic to suggest that things would improve for the last confrontation.

The build-up to the San Marina Grand Prix started at Imola on the Tuesday of race week. Roberts and Lawson were practicing with their new teammate, Carlos Lavado. The Venezuelan had won the 250 world championship on his semi-works Yamaha and was given a chance to ride a 500 for the first time in recognition. He could not really be expected to figure in the battle for the first three and in fact crashed in practice, injuring his ankle badly enough to put him out of the event.

Spencer didn’t bother with the first day of unofficial training. He had never done a large number of practice laps at other GPs and one of his mechanics commented that there weren’t enough spare engines to do a great deal of practice. All through the season Honda engines arrived from Japan fresh for each race and fitted with new cranks that had been run in on the bench. Cylinders were fitted at the circuit but the cranks never disturbed.

After each race engineers returned to the factory taking the used engines as excess baggage. The effort that Honda was putting into the championship was immense. Not only did they have four riders with two machines and three mechanics each, but a variable number of engineers from RSC in Japan.

On top of that Honda had called on the suppliers of the original equipment for their road machines to back their racing project. Showa supplied the suspension, Nissin the brakes, NGK the spark plugs and Keihin the carbs.

Each company supplied engineers to look after their product. The mechanics didn’t clean carbs or renew the slides; they took them off and gave them to the Keihin man who later returned them cleaned and checked.

There was almost too much pressure at Imola. No one used every session and there was an eerie atmosphere, a lack of urgency despite the pressure that surrounded both teams. No one quite knew when to kick themselves into gear to build up to a peak for Sunday’s race. Even when timed practice started on Friday there were few clues as to the likely outcome.

The first sessions were wet. If it rained for the race Honda was probably facing defeat as Dunlop was able to supply better full-rain tires to Yamaha than Michelin could to Spencer. Practice on Saturday was dry and Roberts and Spencer were in a class of their own. Lawson could not be discounted. He had had engine trouble and was confident that with that cured he would be up with them.

Roberts knew that it was no good merely winning the race. He intended to practice positive tactics to help Lawson.

From the start of the race he did just that. Spencer made his usual rapid start but Roberts soon began to close. Lawson was back in seventh but he too was making up places.

Once Roberts caught Spencer he began to try to slow him down. He used the five chicanes at Imola perfectly by getting in front and then slowing in the chicanes where Spencer could hardly pass.

Both riders’ tactics and riding styles all year had been dictated by the machines. The Yamaha was more powerful, but was heavier to steer and impossible to change line with. The Honda, though less powerful, allowed the rider to use the power well by being maneuverable. Spencer could get the power on earlier coming out of turns and was always quicker through traffic.

Spencer used his machine perfectly at Imola. He was warned of Lawson’s approach and though Lawson got to within six seconds of the leading pair, Spencer was always able to quicken the pace just enough to stay out of Lawson’s grasp. Every so often through the 25 lap race, Spencer took the lead and put in a quicker lap to reopen the gap.

Roberts won the race but Spencer took the championship, six wins each, but two more points for the young pretender.

As soon as Spencer crossed the line his team began to get out the T-shirts that proclaimed him champion. They had obviously been ordered in confidence. While Yamaha men were downcast at losing, it looked as though many of the Honda engineers were as much relieved as thrilled. At last the massive investment had born fruit.

Twenty-four years of not winning the 500cc World Championship since they first entered a grand prix (the 125cc Isle of Man TT in 1959) had put an ever mounting pressure on Honda to succeed. They won titles in all the other solo classes, 50, 125, 250 and 350, but the crowning victory had eluded them. Hail wood came closest in 1967 when he and Giacomo Agostini, riding the MV, tied on points. Ago took the title on better race results. What the honor of Honda could not quite cope with was the next chapter in their battle to win the 500 title: the ill-fated NR500 four-stroke.

When it was announced that Honda would return to the world championship chase in 1979 after an absence of 12 years and would do so with a four-stroke, the racing world was stunned. What made Honda think that they could overtake all the development lead the two-stroke had gained in the meantime? It has also been suggested that the men who decided to go racing did not know that since they withdrew from racing in the Sixties, the rules had been changed and there was now a limit of four cylinders on the 500 class.

Those who knew the limits of four-stroke technology maintained that to compete with an equal capacity twostroke, a four-stroke would need either a turbocharger, a supercharger or twice as many cylinders. Honda tried their best with a normally aspirated Four.

They used 32 valves, eight per cylinder. The pistons and bores were oval to accommodate the two lines of four valves. They tried aluminum monocoques to reduce the weight, they used a slipper clutch to reduce the rear wheel hopping on the overrun, they tried three completely different engine designs, and revved them to 18,000 rpm, but it was all to no avail. They did more with a four-stroke than anyone else had ever done. In the end those annoying people who knew better at the beginning were still able to say “I told you so.”

And while Honda was pouring millions of man-hours and dollars into the NR, Yamaha and Suzuki added another three 500cc titles to their books and smiled at Honda’s folly.

There was simply no way Honda could stand merely to withdraw from racing again, they had to win that championship at whatever cost.

And so it was that Shinichi Miyakoshi was told to build a road race grand prix winner. He had designed successful motocrossers and so he put three MX cylinders together on a common crankshaft with simple reed-valve porting. Many of those who had said the four-stroke could not succeed also looked at the threecylinder, two-stroke ranged against the four-cylinder, disc-valve opposition and shook their heads.

The non-believers were wrong: the NS won three grands prix in its first year. Honda was very nearly unlucky in the timing of the oppositions’ development curves. In 1982 the RG500 Suzuki was still at its peak, a superbly balanced machine that was fast and reliable. Franco Uncini was its perfect match. And the Honda’s failures, in Spain and Sweden, thanks to a broken chain coupled with a design fault that gave the front end a tendency to wash out, meant that Spencer had to be content with third place in the championship.

At the beginning of 1983 Honda was conspicuously on top. Suzuki ran right off the end of their development curve. The ‘83 machine was too light, too compact. Its frame was fragile and flexed. The engine, smaller even than the ‘82 machine, which was a scaled down ‘81 version, had too-little crankcase volume and too-small disc valves. While Suzuki took one, two and then three steps backwards in an attempt to find a combination of modified frames and engines that would work, Randy Mamola rode his heart out. He finished every race drenched in sweat, having put more into his riding than he had ever had to before. Mamola is still hungry for that world championship. Franco Uncini, his teammate, was chewing on his, and realized early on that he wasn’t going to get a second mouthful in ‘83.

All season Mamola played second fiddle to the number one attraction, the “Kenny and Freddie show.”

If the Honda started out in front, Yamaha was determined to make up ground fast. The disc valve V-Four was unveiled at the Austrian GP in early ‘82. It was never a huge success and KR won only one GP, the Spanish. For 1983 the machine had been completely redesigned even if the engine looked the same.

The Yamaha worked, almost from the start, but as far as the world championship effort was concerned the team> wasted valuable time going to Daytona where they rode the square Four. Even though they won, they missed valuable practice in the rarified atmosphere at 6000-ft. Kyalami in South Africa, where the first round took place one week after Daytona.

The Yamahas never ran properly throughout practice and the race. They didn’t want to start, they overheated and were down on power. It was a track that should have suited them with a mile-long straight but Roberts never got near to Spencer and finished second with Ron Haslam third on the second Honda.

Honda made it a clean sweep at the next round in France with Spencer ahead of Lucchinelli and Haslam. Yamaha’s only consolation for Roberts’ fourth was the fact that he had been leading until his exhaust pipe split. Lawson never started. He was torpedoed on the line in an incident that also put both Mamola and Uncini out.

Mamola’s legacy of that incident was a broken bone in his ankle that made him wear a temporary cast when he wasn’t racing. It didn’t stop him from finishing second at the next round, the Italian Grand Prix at Monza. It was the first ever American one, two and three, but it didn’t include Roberts. Mamola had finished behind Spencer and ahead of Lawson. Roberts was stranded out on the circuit with a dry fuel tank.

It was Spencer’s third win in a row. He now led the championship table by 25 points from Roberts and Haslam. It was the second time in a row that Roberts had led the race only to lose.

Roberts had seemed to have the race in the bag, Spencer and Mamola were beaten. Then he simply ran off the track. “I goofed. I lost concentration passing some slower guy.” It was approaching one of the chicanes and the Yamaha ran into one of the shale safety traps. It went down with Roberts still holding onto the bars, still blipping the throttle and with the clutch pulled in.

He was quickly back on his feet and going again but had dropped to third. While he regained his composure Lawson pushed him back to fourth. Then the petrol ran out.

Why Roberts’ tank ran dry while Lawson’s was still comfortably wet is a secret guarded by the team. They had topped both bikes up on the line after the warmup. Was it that Roberts used more by lapping faster and during his excursion into the dirt, or was his tank smaller? The tank he used may have been intended to be used with the frame tubes also filled with fuel. The first ‘83 frames were built with filled caps and outlet tubes until it was pointed out to the designer that the regulations state that only one fuel tank can be used.

At the next clash, the German Grand Prix at Hockenheimring, the weather took a hand: It disrupted practice, which pleased Roberts and Lawson not at all. They felt that they were still racing from behind and needed all possible track time.

Race day came and it rained again. The race was delayed but eventually run in the dry. This time the misfortune was aimed at Honda. Haslam retired early with a split exhaust and then the same thing happened to Spencer’s machine but not quite as crippling. He lost power and was passed by Katayama and Lucchinelli. It didn’t look as though Spencer’s Honda would last the distance but he was saved by the rain which fell again and caused the race to be brought to a premature end.

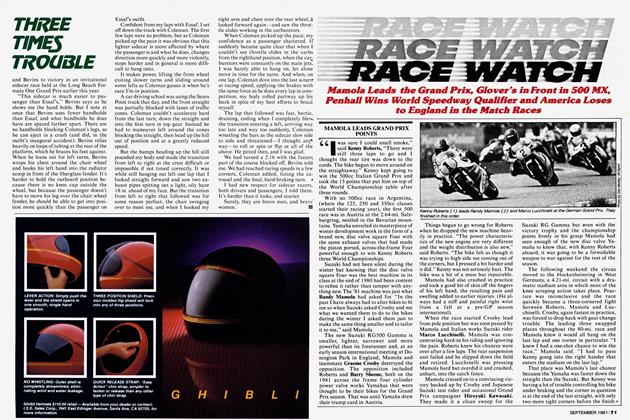

The next round in Spain was one of the great races of the year. It was the first round of the clear-cut, titanic struggles between Spencer and Roberts, with no one else in sight. Haslam crashed and cracked a bone in his arm trying to keep up. Spencer led from his now customary lightning start but Roberts was soon into his stride and rapidly reeled him in.

When Roberts took the lead it looked as though he had the race won, but in the 45-mim race round the twisty, undulating Jarama circuit in the near 100° heat, the advantage swung back and fourth. The Honda was definitely easier to handle and Roberts had to use the grass at least once as he fought to control the powerful Yamaha. The advantage swung from one to the other and it was Spencer who held it at the crucial moment.

In Austria, around the high speed Salzburgring, Roberts and the Yamaha were in a class of their own. KR was well out in front, when Spencer had his crankshaft rattle to destruction. Lawson was in fine form, taking second from Mamola who had “used up my tires in the first few laps trying to hang onto the Yamahas and Hondas.” It was another clean sweep for America and it closed the points gap between Spencer and Roberts to 21.

The development pendulum was definitely swinging Yamaha’s way. The V-Four was developing plenty of power and the Dunlop tires were good enough to allow Roberts to use most of it. Spencer on the other hand was having to ride harder and harder to keep up. He was demanding more and more of his Michelins and the question was when would he ask too much?

The question wasn’t answered in Yugoslavia because what should have been a classic confrontation went flat when the Yamaha wouldn’t start. Roberts was a mile behind Spencer by the time he got underway and though he cut through the field with seemingly demonic abandon, he could get no higher than fourth. In third was Lawson who amazingly received no team orders and effectively cost Roberts two vital points. There were some harsh words spoken that evening.

The situation was somewhat reversed at Assen when Roberts won the Dutch TT. Spencer’s tires definitely failed to maintain the performance he demanded of them and he was beaten out of second place by Katayama. No team orders there, either. In Belgium the race pattern was repeated. Spencer led from a rapid start only to be overhauled and soundly beaten by Roberts as his front tire started to slide and he nearly crashed. Mamola once more joined them on the rostrum.

At Silverstone no one could keep up with Roberts. The race was run in two parts due to the accident that claimed the lives of Norman Brown and Peter Huber. Roberts clearly mastered both legs but second went to Spencer as the result of a peculiar aggregate scoring, thanks to his performance in the short first race, despite the fact that he was fourth, beaten by Mamola and Lawson, in the second.

Roberts faced up to the Swedish GP at Anderstorp knowing that the circuit with its tight corners suited the Honda. He was five points behind Spencer and practice confirmed that the man from Shreveport would be hard to beat. The old routine once more: Spencer led, Roberts reeled him in, passed and pulled away. It made a nonsense of the practice times: It was the tires again as Spencer revealed later. “They never seem to work in the race the same as they do in practice. This time they just refused to warm up, they chattered badly till near the end when they started to work.”

As the tires started to work Spencer closed once more on Roberts. Accelerating down the back straight for the last time with only two tight corners left to go Roberts still led by a handy margin and he had the advantage of the Yamaha’s speed down the straight. He wanted to make use of it and he accelerated hard. As he did so the front wheel came up and kept rising. In the end KR had to ease off and by the time the wheel was back on the ground Spencer had neatly tucked into his slipstream.

As they reached the end of the straight Spencer pulled out of the slipstream and alongside the Yamaha, on the inside for the approaching righthander. Roberts, seeing him there and realizing that he couldn’t let Spencer take the inside line, let off the brakes and moved ahead. At the last moment he dived across the Honda’s nose into the turn. But he was a fraction too late and too fast. He ran wide onto the dirt. Spencer did the same but only for a few feet and as the Honda accelerated past, Roberts was still fighting to get the Yamaha back onto the tarmac.

Roberts was stunned. He said some hard words about Spencer's riding, saying that if he wanted the championship that badly he could have it. But in the end he was only mad at himself.

“I completely underestimated him. I should never have let him do it,” reflected Roberts a month later after he had lost the world championship at Imola. “I suppose that is what sticks as the place where I lost the championship because Spencer made a mistake but he got the points. On the other hand we could have done with 10 points when I ran out of gas at Monza or two more points in Yugo when I was fourth instead of third.”

After Sweden, there was little Roberts could do. He won the final race at Imola and he tried to help his partner beat Spencer, but not even the legendary Roberts in top form could take both first and second. He finished this season, perhaps his last, having beaten his rival on every occasion when they both had no excuses. All except for Sweden.

Had the world championship gone the other way Spencer would have been able to point at the places where he lost points, where Takazumi Katayama beat him into second at Assen, for example.

Such reasonable explanations are not written in the record books. They only show that Freddie Spencer, Shreveport, Lousiana, won his first world title, very likely the first

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

December 1983 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

December 1983 -

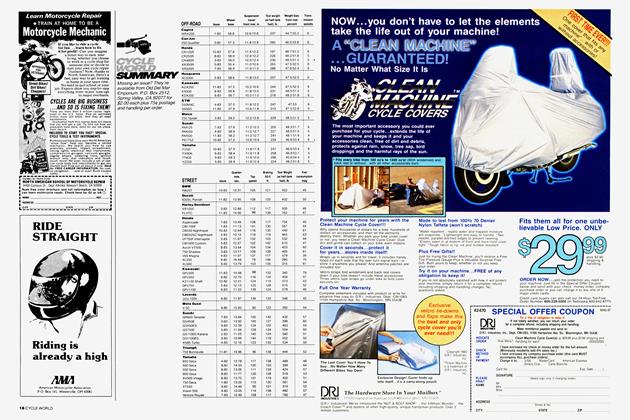

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

December 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

December 1983 -

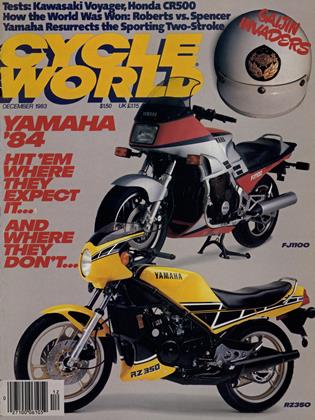

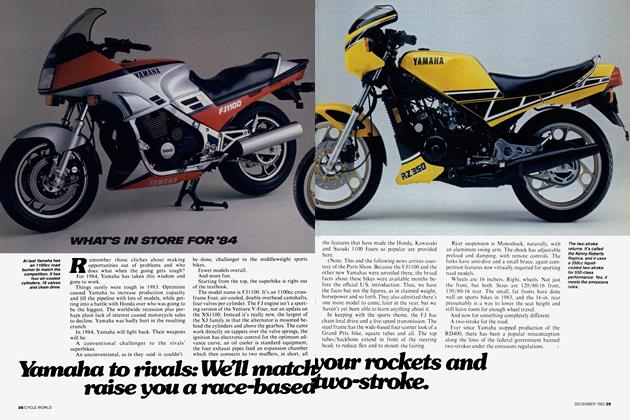

What's In Store For '84

What's In Store For '84Yamaha To Rivals: We'll Match Your Rockets And Raise You A Race-Based Two-Stroke.

December 1983 -

Features

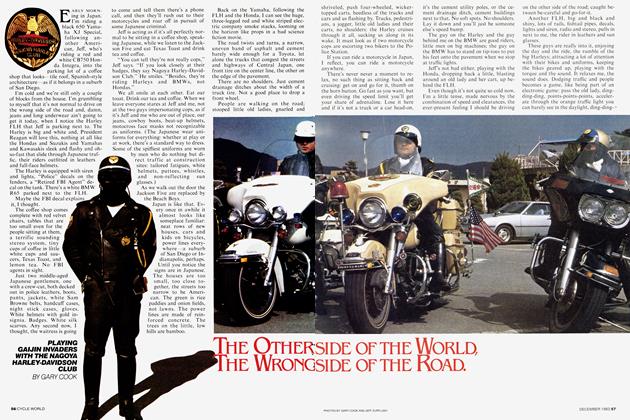

FeaturesThe Other Side of the World, the Wrong Side of the Road.

December 1983 By Gary Cook