JIM PARKS GOES TO AFRICA

JIM PARKS

Remember His Last Adventures? Some Of Our Readers Expressed Their Disbelief Quite Vitriollcally. So, In The Spirit Of "Let Them Eat Cake," We Offer The Crocodile/Boot Affair, The Tsetse Fly Inspector And Other Oddities.

PART ONE OF TWO PARTS

THE WORD "Africa" conjures in the minds of most Americans, visions of wild animals roaming vast grasslands and dense, hot jungles. But after spending two years traveling in South America (CW, Dec. '68-Jan '69), I was prepared to take nothing at face value and decided to see for myself. I would attempt my second overland journey by motorcycle, this time from southern Africa, north across the continent to Europe and Russia. It was to be my "Cape Town to Moscow" tour.

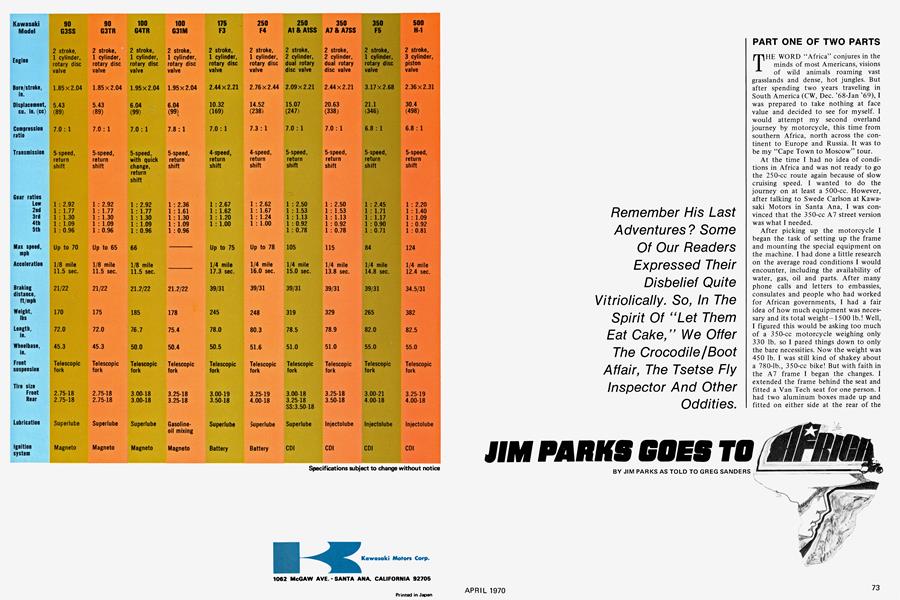

At the time I had no idea of conditions in Africa and was not ready to go the 250-cc route again because of slow cruising speed. I wanted to do the journey on at least a 500-cc. However, after talking to Swede Carlson at Kawasaki Motors in Santa Ana, I was convinced that the 350-cc A7 street version was what I needed.

After picking up the motorcycle I began the task of setting up the frame and mounting the special equipment on the machine. I had done a little research on the average road conditions I would encounter, including the availability of water, gas, oil and parts. After many phone calls and letters to embassies, consulates and people who had worked for African governments, I had a fair idea of how much equipment was necessary and its total weight—1500 lb.! Well, I figured this would be asking too much of a 350-cc motorcycle weighing only 330 lb. so I pared things down to only the bare necessities. Now the weight was 450 lb. I was still kind of shakey about a 780-lb., 350-cc bike! But with faith in the A7 frame I began the changes. I extended the frame behind the seat and fitted a Van Tech seat for one person. I had two aluminum boxes made up and fitted on either side at the rear of the bike. But after filling the boxes with equipment and clothes, I had one helluva back-heavy Kawasaki with two threegallon cans still to be mounted. Putting these cans in the rear would be suicidal, so the only alternative was to mount them on either side of the front wheel, which I did. At this stage I was a little uncertain as to how the machine would handle with an extra 60 lb. of unsprung weight. But my fears were short-livedshe handled beautifully. Of course, under 10 mph it was a little rough, but I got used to this after a while.

Next came a Wixom fairing and windshield, the last of the extras needed for the trip. Completely loaded with gear and gas, the total weight was 760 lb.

At this stage, publicity of the marathon began to play its part. The press had shown considerable interest in the trip, and it occurred to me that manufacturers of products used on the bike might be interested in sponsoring part of the journey. I was well rewarded for my efforts. Dick Cudner of Champion

Spark Plug Company in Toledo, Ohio, was searching for a stunt to test the new plugs for Kawasaki's capacitive discharge ignition. Dunlop of England supplied tires and Torco Oil contributed the lubricants needed.

At last all was ready. I loaded the bike, which now resembled a twowheeled tank, onto a freighter bound for Cape Town, South Africa. Then I flew to London where I took a boat to Cape Town.

I certainly had not expected the big city which greeted me as we sailed into the harbor at Cape Town. Table Mountain rose dark and majestic in the background. The sun's copper glow spread over the great flat mountain top and was slowly crawling down to bathe its rugged slopes and the still-sleeping city. The formations called Lion's Head and Signal Hill thrust out toward the sea. We docked alongside one of the many quays in the bustling harbor. And then began my new adventure.

I had the good fortune to meet Dr. Christian Barnard during my two-week stay in Cape Town. Naturally, we discussed hearts and motorcycles, usually at lunch, as we lived in the same hotel. He was as much interested in my trip as I was in the heart transplants he had performed. He even declared that he wished he were in my shoes, which made me feel quite proud.

Cape Town had a lot to offer in the way of social life, as I was soon to find out. Cape Town girls are known to be among the best looking in the world and one day while touring around I stopped one of them to ask directions. Her name was Barbara, and we spoke for a while, I about the trip and she about work and her home. She told me she was a native-born South African of English descent. Her dusty blond hair and beautiful accent were more than sufficient to attract me to her.

We agreed to meet in Spain as she also was preparing for some traveling and sightseeing anyway. I knew it would be a while before I would see her again.

The big white ship pulled in right on schedule. I expected to wait a long time before I even saw the motorcycle, but to my surprise the bike and a couple of packages were the only items unloaded. One of the officers said that it cost the company close to $3000 to stop at Cape Town to deliver freight. My bike cleared customs without any hitches and after a few last minute preparations and sad farewells, I was ready to start.

I left early in the morning, heading due east, along what is called the Garden Route. It stretches for 1200 miles from Cape Town to Durban, which is the second largest city in South Africa. My first stop was 480 miles from Cape Town at Oudtshoorn, famous for its ostrich feather industry.

After a restless night in unfamiliar territory, I breakfasted on an ostrich egg, or rather part of an egg (the average ostrich egg is big enough for about two dozen servings). It tasted terrible and I don't recommend it. I spent the day watching the ostrich ranchers show off their prize birds and a few people tried to ride them.

Early next morning I headed north along the sandy shores of the Indian Ocean. I passed more ostrich farms and saw riders mounted on their backs. It is a magnificent sight to see these birds in full gallop jumping over high rocks and bushes at speeds over 35 mph. By now I was curious enough to want to try this out for myself. As it happened, the owner of the next petrol station I stopped at also owned an ostrich farm. I asked to try the two-legged "bird bike." He thought this a strange request since Americans usually drive big cars with the windows rolled up. He gave me his blessing at my own risk.

I thought some of those new, big bore two-strokes were a handful, but man! Joel Robert would become very religious after a 50-ft. ride on an ostrich. I was lucky to have stayed on for only about 80 feet. I must have nearly strangled the ostrich as we flew across rocks, bushes and almost into a fence.

About 700 miles later, in the Transkei area, I came across my first tribesmen, the Xhosa. The "X" is pronounced with a click of the tongue. The Xhosa are sometimes called the "Red Blanket People" because they cover their bodies with red cloaks and wear large turbans. The Xhosa reservation is one of the largest in South Africa. While traveling through it I passed two native boys covered with white ashes from head to toe. This is part of their maturity rites and is necessary for them to be accepted as full fledged male members of the tribe. They must go through this ritual until their fathers tell them they are men, usually about a month to six weeks later. There is the sad old story of the boy whose father died while he was wearing the ashes and he had to wear them forever.

I reached the end of the Garden Route and cut a trail inland toward Johannesburg, the capital of South Africa. It has a population of almost 1,000,000 people; the second largest city in Africa. The city sprang up almost overnight after the discovery of gold there in 1884. It has since become a modern metropolis with skyscrapers, smart shops, museums, art galleries, lovely homes and beautiful wooded parks. It was here that I witnessed the tribal dances which have become a major tourist attraction in South Africa. On this particular weekend there was to be a dance contest among some 28 tribal groups which lasted all day and part of the night.O~e Zulu chief was so impressed with my overladen workhorse that he wanted to buy it. I told him it wasn't for sale, but he insisted and offered 22 goats and a man to herd them for me as long as any one of the original goats lived. He was quite a businessman and continued to offer more goats and men in the hope that I would give in. I finally asked him why he wanted the motorcycle so badly. He explained that it was the only vehicle he had seen with two rear seats and only one front seat, and that it would be ideal for him and his two wives as they continually squabbled about who would ride next to him on the wagon. I extended my sympathy but declined his offer.

Once again I was northbound, this time for Bulawayo, Rhodesia, the second largest city in Rhodesia with a population of 250,000. The streets of Bulawayo (Place of Slaughter) are so wide that a span of nine horses can make a "U" turn on them. At this point I headed northwest toward Victoria Falls, which the native populace calls "The Smoke that Thunders." I wanted to get some pictures of the motorcycle at the falls but first had to convince the gate keeper that I was an important international photographer. When I pointed my camera at him and turned the electric eye off and on, which made the sound of a shutter, those pearly white teeth appeared from ear to ear and I knew I was in. With the thunder of the falls louder than the bike, I was able to move freely without arousing the other guards. The channel is about 80 feet at its widest point and 350 feet deep. The noise was so great that after about the first 100 feet I had to put plugs in my ears. But when a breeze came, it cleared away the mist and revealed a spectacular scene. We saw a million rainbows, a mass of color many stories high.

My next stop was Botswana, a country west of Rhodesia and north of South Africa. It is separated from Zambia by the Zambezi River which feeds the Victoria Falls. While in Botswana (formerly Bechuanaland), I came upon a fascinating area, the Chobi Game Reserve. It was here, too, that I saw proof of something that had been told me earlier, namely that motorcycles are forbidden in these game reserves. I was determined not to be put off by this triviality. I hastily made my way to a nearby village and asked about other ways of getting into the reserve, explain ing that I was not allowed in on the motorcycle. I was informed that there were many ways to enter, but it would cost me to find them. Bargaining began and the price was eventually reduced to a handful of change.

I next tound myseit and tile motor cycle aboard a wagon drawn by oxen. I held on and somehow managed to en dure one of the roughest rides of the entire trip. After what seemed to be two weeks we arrived. "Here," he said. I slowly heaved my stiff and sore body out of the cart and looked around. Nothing. Miles of nothing but plains, and patchy, waist-high grass. I asked my guide what he meant by "here." He explained that we were about five miles inside the reserve and that if I would look to my right down a hill, I would see the road from the main entrance gate. He also warned me about wild dogs. They roam in packs and will attack people who camp out. All the other wild animals were quite afraid of motorcycles as the rangers often used them to scare the wild animals away from the rest areas and camp sites in the reserve at night. But wild dogs might attack anything that moved.

Coming over a rise I looked down to the plains to see a spectacular array of wild life. For miles there were groups of running and jumping animals-zebra, water buffalo, gazelle, impala, and gi raffe.

But the day was becoming hotter and I caught glimpses every now and then of the Zambezi River beyond the road. I got the brilliant idea to take a dip in the river and rejuvenate my baked out spirit.

I found a pleàsant spot to park the motorcycle along the river under some weeping willows. As I made my way toward the muddy Zambezi, I noticed a sign in the partly washed away shore: "Swimming is suicidal because of croco dues." It seemed strange that a river so peaceful and calm could contain any thing dangerous. Visualizing crocodiles with huge jaws and teeth, I decided not to challenge the sign.

I did, however, intend to wash off my boots with the river water. The boots measure about 12 inches tall from the heel up. Holding my right boot at the top, I dipped it into the water to fill it up. Suddenly, to my horror, I realized that the last eight inches of my boot were deep in the jaws of a crocodile, while my trembling hand still gripped the top half of the boot. Apparently, while I was scrutinizing the sign, the crocodile had crept up to the shoreline and submerged himself at the water's edge. He was just waiting for a nice fat leg to step into his meat grinder. It made my blood run cold.

But my boot had not yet disappeared from view and was still moving about above the water. Thinking quickly, I grabbed the sign and brought it down hard just behind my boot. The "suicide sign" made good contact, for it seemed that the whole river trembled and shook when I hit that overgrown boot-hungry lizard. The boot came floating up and I snatched it out of the water in a split second. I was later told that the croco diles normally won't hesitate to come out of the water. It had not even occurred to me that he might have pursued me after discovering that he had the meat wrapper instead of the meat. After a close call like that, I decided to leave the drama to movie heroes.

I was now headed for Salisbury, the capital of Rhodesia. It has a population of about 500,000 and a pleasant climate with an average temperature annually of 75 degrees. In Salisbury I visited some of the motorcycle shops and was told about an up and coming race. I never realized that people could be so friend ly. There was no sales talk, just friendly conversation.

Naturally, I stayed for the race that weekend. It was like being back on the West Coast ten years ago. There they were, in all their glow: the old Manx Norton and AJS 7Rs and all the rest of the old four-strokes that used to domi nate the grand prix circuit. Two of the new Japanese machines were there, and by the time they had completed the first lap it looked as if they were in a different race, they were so much ahead of the rest of the field. I really enjoyed this race as it was held in a very friendly and sportsmanlike manner with everyone working together and helping one another as a community project.

Shortly afterward I was headed north once again. As I turned and looked down toward the beautiful city of Salisbury, I could not help but feel a bit sad that political problems should lie so heavily on a country that has to be the nicest place that I visited on any of my travels on this globe.

The trip from Salisbury to the border of Portugese East Africa (Mozambique) is about 210 miles on some of the worst roads Eve ever encountered. But no sooner had I arrived at the border than I was greeted with the announcement that I could not enter the country without a visa. I had seen the consulate of Mozambique while in Salisbury and was told that while traveling on a U.S. passport I did not need a visa. Beating a hasty retreat to Salisbury, I made it to the consulate before it closed. I was determined to be out of Rhodesia before that evening. This turned out to be a big mistake, almost a fatal one. I had covered about 180 miles when I heard a loud popping sound and to my right saw flashes of light. Those flashes of light were gunfire! My first reaction was to stop and yell like hell that I was a good guy. But I had been warned about terrorists operating out of Zambia. The Rhodesian army and police had been having trouble with them. I looked in the direction of the gunfire a moment too long and ran into soft sand. I was thrown to the ground and my bike was on its side. I reached up and turned off the lights and engine and attempted to lie as still as possible, but I was shaking so much that I could hardly do even that. Next, I heard voices about 50 yards away. They seemed to be to the right of the road and slightly behind me. It was so dark that I could not see more than ten yards in any direction.

All of a sudden the jungle around me

seemed to roar with the sound of engines coming from the other side of the hill. I was afraid that there would be more shooting and decided to warn whoever was coming of the immediate danger. As the sound grew louder, the headlights of an Army Jeep appeared like two glowing eyes in the night. I immediately recognized them as belonging to a Rhodesian Police Patrol Jeep.

I kept a flashlight in the sleeping bag rolled up behind me on the bike, so all I had to do was to reach into the center and pull it out, which I hastily did, but not before positioning myself behind a tree near the road. I took careful aim at the Jeep with my flashlight and flashed three times The searchlights went on immediately to catch in their beams the last of about 10 natives carrying guns and boxes across the road. Other Jeeps pulled up alongside the leader and troops jumped out and began firing at the retreating figures as they disappeared into the jungle. By this time the trucks were about 50 feet from my bike and I yelled as loud as possible that I was an American visitor and they were not to shoot. I was instructed to come out from behind the tree with hands high.

Meanwhile, other soldiers were in hot pursuit of the natives, the darkness having given way to flares, searchlights and headlights. The sound of machine gun and rifle fire echoed through the jungle. Officers could be heard barking orders to the soldiers as they clambered through the dense woods.

I put out my right leg first and slowly the rest of my body followed suit. They encouraged me to come forward with words like: "Easy like, old chap." After explaining the circumstances and showing my passport and papers, including a paper clipping relating to my trip, they seemed convinced. I was informed that they had had reports that of some strange movements in this area. It was this information that had brought them to my rescue. It was like something out of the movies when the cavalry saves the settler from the wild Indians. We walked over to my bike to inspect the damage. I almost fell over when my attention was brought to the three bullet holes in my bike. One went through the fairing and one through the top of my windshield; the third bullet had come from the side and hit my sleeping bag. As I kept most of my clothes rolled up in my sleeping bag, I now wear two T-shirts and one pair of levis with holes in them.

The officer told me that I would have to stay on for a preliminary hearing to testify and possibly identify any suspects, as living witnesses were rather hard to come by. I was then allowed to head back for Salisbury. But after a mile or two I pulled over and waited in some dense bush for them to pass, after which I headed north as fast as I could, and made the border before dawn.

When I arrived at the gate I was asked if I were the one who was shot at during the night. After explaining that I was, I hastily added that I was just going to the coast for a couple days and would be returning for the hearings. This time I was allowed to pass.

The route through Mozambique was very mountainous and dusty. Twenty miles inside the country I came across a sign that read: "Stop for Tsetse Fly Inspection," and a little farther on a native stood by the roadside waving me down. I pulled over and he said he had to inspect me and my motorcycle for the fly. As he walked around the motorcycle, I asked him if he had caught any lately. He replied that although he had been here for two years he hadn't seen one yet. The government gave him a check every month, plus brought new grass for his cow every three months. With the big smile of a millionaire, he added that this was a great way to live. It was quite humorous to watch him walk around the motorcycle with his fly swatter in one hand and a large, very used looking diagram of a tsetse fly in the other. Then, with a satisfied look on his face, he pronounced that I was clean.

I made it to the Zambezi River once again. It was more than half a mile across at this point and flowing very fast. The barge made only four trips a day. I had just missed the last one so I set up my tent at this point and settled down for a quiet night on the river. (To be continued.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

April 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

April 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

April 1970 By John Dunn -

Features

FeaturesA Mind of Its Own

April 1970 By Bob Ebeling -

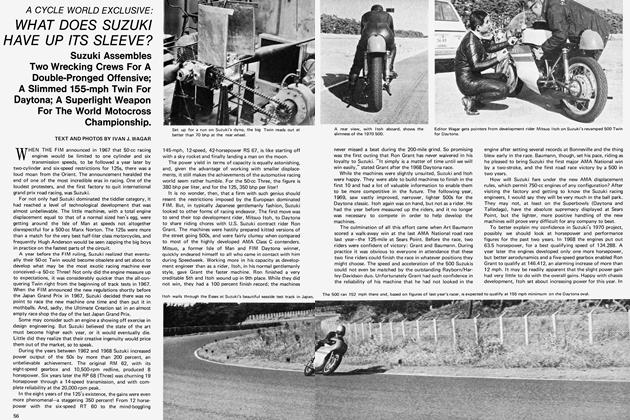

A Cycle World Exclusive

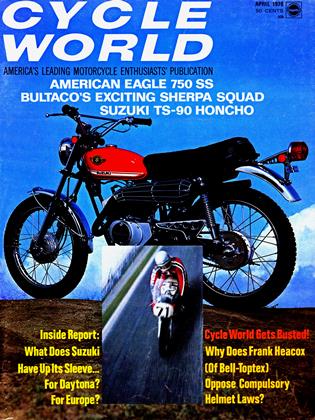

A Cycle World ExclusiveWhat Does Suzuki Have Up Its Sleeve?

April 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar