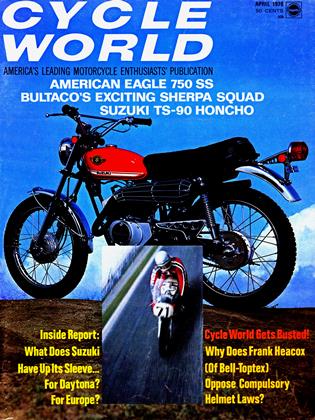

WHAT DOES SUZUKI HAVE UP ITS SLEEVE?

A CYCLE WORLD EXCLUSIVE

IVAN J. WAGAR

Suzuki Assembles Two Wrecking Crews For A Double-Pronged Offensive; A Slimmed 155-mph Twin For Daytona; A Superlight Weapon For The World Motocross Championship.

WHEN THE FIM announced in 1967 that 50-cc racing engines would be limited to one cylinder and six transmission speeds, to be followed a year later by two-cylinder and six-speed restrictions for 125s, there was a loud moan from the Orient. The announcement heralded the end of one of the most incredible eras in racing. One of the loudest protesters, and the first factory to quit international grand prix road racing, was Suzuki.

For not only had Suzuki dominated the tiddler category, it had reached a level of technological development that was almost unbelievable. The little machines, with a total engine displacement equal to that of a normal sized hen's egg, were getting around the Isle of Man at speeds not altogether disrespectful for a 500-cc Manx Norton. The 125s were more than a match for the very best half-liter class motorcycles, and frequently Hugh Anderson would be seen zapping the big boys in practice on the fastest parts of the circuit.

A year before the FIM ruling, Suzuki realized that eventually their 50-cc Twin would become obsolete and set about to develop what may be the most exotic racing machine ever conceived—a 50-cc Three! Not only did the engine measure up to expectations, it was considerably quicker than the all-conquering Twin right from the beginning of track tests in 1967. When the FIM announced the new regulations shortly before the Japan Grand Prix in 1967, Suzuki decided there was no point to race the new machine one time and then put it in mothballs. And, sadly, the Ultimate Creation sat in an almost empty race shop the day of the last Japan Grand Prix.

Some may consider such an engine a showing off exercise in design engineering. But Suzuki believed the state of the art must become higher each year, or it would eventually die. Little did they realize that their creative ingenuity would price them out of the market, so to speak.

During the years between 1962 and 1968 Suzuki increased power output of the 50s by more than 200 percent, an unbelievable achievement. The original RM 62, with its eight-speed gearbox and 10,500-rpm redline, produced 8 horsepower. Six years later the RP 68 (Three) was churning 19 horsepower through a 14-speed transmission, and with complete reliability at the 20,000-rpm peak.

In the eight years of the 125's existence, the gains were even more phenomenal—a staggering 350 percent! From 12 horsepower with the six-speed RT 60 to the mind-boggling

145-mph, 12-speed, 42-horsepower RS 67, is like starting off with a sky rocket and finally landing a man on the moon.

The power yield in terms of capacity is equally astonishing, and, given the advantage of working with smaller displacements, it still makes the achievements of the automotive racing world seem rather humble. For the 50-cc Three, the figure is 380 bhp per liter, and for the 125, 350 bhp per liter!

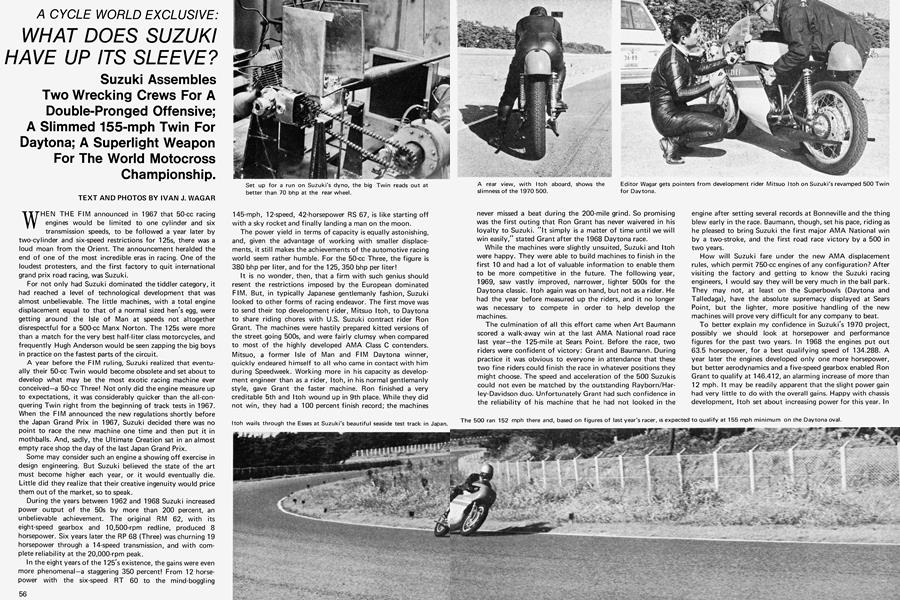

It is no wonder, then, that a firm with such genius should resent the restrictions imposed by the European dominated FIM. But, in typically Japanese gentlemanly fashion, Suzuki looked to other forms of racing endeavor. The first move was to send their top development rider, Mitsuo Itoh, to Daytona to share riding chores with U.S. Suzuki contract rider Ron Grant. The machines were hastily prepared kitted versions of the street going 500s, and were fairly clumsy when compared to most of the highly developed AMA Class C contenders. Mitsuo, a former Isle of Man and FIM Daytona winner, quickly endeared himself to all who came in contact with him during Speedweek. Working more in his capacity as development engineer than as a rider, Itoh, in his normal gentlemanly style, gave Grant the faster machine. Ron finished a very creditable 5th and Itoh wound up in 9th place. While they did not win, they had a 100 percent finish record; the machines never missed a beat during the 200-mile grind. So promising was the first outing that Ron Grant has never waivered in his loyalty to Suzuki. "It simply is a matter of time until we will win easily," stated Grant after the 1968 Daytona race.

While the machines were slightly unsuited, Suzuki and Itoh were happy. They were able to build machines to finish in the first 10 and had a lot of valuable information to enable them to be more competitive in the future. The following year, 1969, saw vastly improved, narrower, lighter 500s for the Daytona classic. Itoh again was on hand, but not as a rider. He had the year before measured up the riders, and it no longer was necessary to compete in order to help develop the machines.

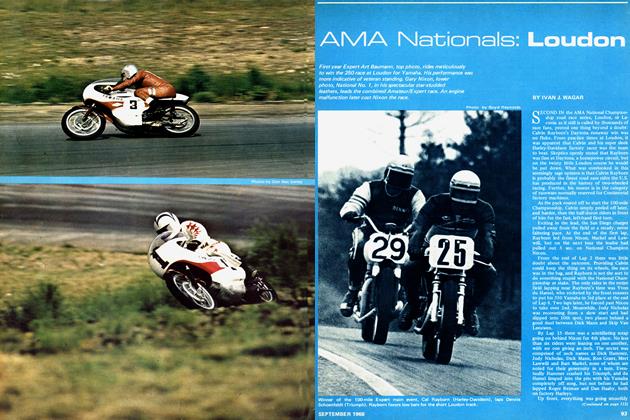

The culmination of all this effort came when Art Baumann scored a walk-away win at the last AMA National road race last year—the 125-mile at Sears Point. Before the race, two riders were confident of victory: Grant and Baumann. During practice it was obvious to everyone in attendance that these two fine riders could finish the race in whatever positions they might choose. The speed and acceleration of the 500 Suzukis could not even be matched by the outstanding Rayborn/Harley-Davidson duo. Unfortunately Grant had such confidence in the reliability of his machine that he had not looked in the

engine after setting several records at Bonneville and the thing blew early in the race. Baumann, though, set his pace, riding as he pleased to bring Suzuki the first major AMA National win by a two-stroke, and the first road race victory by a 500 in two years.

How will Suzuki fare under the new AMA displacement rules, which permit 750-cc engines of any configuration? After visiting the factory and getting to know the Suzuki racing engineers, I would say they will be very much in the ball park. They may not, at least on the Superbowls (Daytona and Talledaga), have the absolute supremacy displayed at Sears Point, but the lighter, more positive handling of the new machines will prove very difficult for any company to beat.

To better explain my confidence in Suzuki's 1970 project, possibly we should look at horsepower and performance figures for the past two years. In 1968 the engines put out 63.5 horsepower, for a best qualifying speed of 134.288. A year later the engines developed only one more horsepower, but better aerodynamics and a five-speed gearbox enabled Ron Grant to qualify at 146.412, an alarming increase of more than 12 mph. It may be readily apparent that the slight power gain had very little to do with the overall gains. Happy with chassis development, Itoh set about increasing power for this year. In fact, only slight changes to ports, but major alterations to the exhaust system, have brought output from 64.5 to 70.5 horsepower. This increase, plus a few subtle changes in aerodynamics and handling, undoubtedly will still permit the 500 Suzuki to be competitive against machines with a 50 percent displacement advantage.

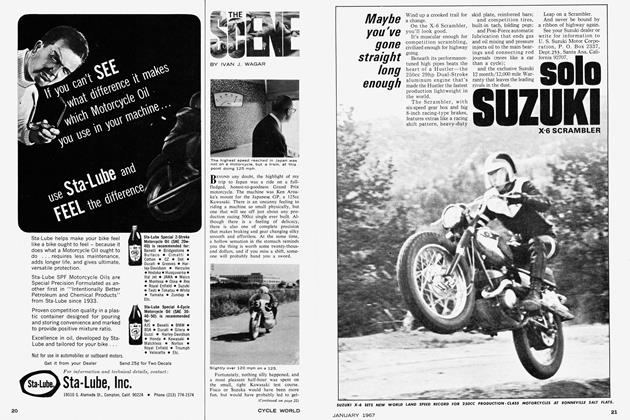

Last year's 500s were turning out 140 mph at Suzuki's beautiful seaside test track in Japan. At Daytona the same machine averaged over 146 mph on the Tri-Oval. This year's TR 500 has peeled four seconds off the previous lap time and recorded a top speed of 152 mph. Even conservative estimates for Daytona should come up with a 155 mph qualifying performance.

CHANGES ARE SUBTLE, BUT PROGRESSIVE

Probably the most amazing part of the TR 500's success story is how much it still resembles the machine you see on the road. True, there have been chassis changes, as permitted within AMA regulations, but the basic design is the same as you can buy from a local dealer. Japanese honesty compels Suzuki to adhere completely to the use of standard engine castings. The cylinders, for instance, are standard units with rather small changes to port size and timing. The exhaust port has been widened from 43 to 57 mm; the height has been raised from 40 to 34 mm. The transfer port width remains standard, but has been raised 2.5 mm only. The only other change from standard is to lower the inlet from 104 to 110 mm from the cylinder top, and to increase the width by 4.4 mm. All of these modifications are well within the scope of the home builder.

The only problem facing the private tuner is the exhaust pipe design. We would think that in this space age era that expansion chamber design is a hard and fast thing; that all that is required to know is gas velocity, gas temperature and port timing, and then sit down at the drawing board or computer and come up with an exhaust system for a two-stroke. That is not so. Despite years of research, Suzuki still finds it necessary to adjust the pipes to the needs. On paper it is fairly simple to come close to the ideal shape for maximum speed, even then very small changes are required to achieve ultimate performance. Experimentation comes into the picture when it becomes necessary to design an exhaust for an engine that must have good power, but also a good power band, at least within the restrictions imposed by a limited number of gear ratios. The AMA, for instance, restricts the number of gearbox ratios to five.

After a great deal of time shuffling back and forth between port and pipe design, the engineers must then find a way to route the pipes so that they do not ground when the rider is cornering under maximum stress. It has happened that, after final machine construction, it was necessary to go back and adjust the ports and pipes after track tests. So, as in so many cases in modern technology, many things may be a compromise. Years of experience at Suzuki have taught the development people that nothing is concrete, unless the engine is to spend its entire life on the dynamometer.

After deciding upon the power band and power peak, it then is necessary to adjust internal gearbox ratios for the circuits where the machine is intended to compete. Naturally this is permissible within the scope of AMA regulations.

Because the slowest corner at Daytona is around 50 mph, and even then some clutch slip is permissible, Suzuki has placed low gear slightly higher than the normal second cog in a street transmission. Top gear, internally, remains the same as standard. The result is that all internal ratios are brought much closer together to take advantage of the narrower power band.

Carburetors, astounding as it may seem, remain the same at 34 mm. The clutch differs from the street component only in that it has one additional plate, with a suitably increased basket size.

To meet the rigors of 160-mph racing speeds, Suzuki has chosen Ceriani front forks and rear suspension units. Also, in the interest of high speed safety, Ceriani brakes are fitted to the TR 500, but will be the same as last year's models.

A problem at Daytona last year was the aluminum rear sprocket. In order to gear highly enough for Daytona speeds, the rear sprocket is almost down to the diameter of the rear hub, and chain velocity over the sprocket is very high. Consequently the aluminum component almost cost Ron Grant his 2nd place last year. For 1970, a steel rear wheel sprocket will be used to accommodate the low rear drive ratio of 2.5:1 on the 500 contender.

Thus far, much has been said about the 500, and very little about the 250. Race fans will not have forgotten the absolutely brilliant ride of Dick Hammer when he came from the back of the grid in 1967 to pass leader Gary Nixon on a Yamaha. With a lap and a half to go, Dick had a footpeg come adrift, losing the rear brake, while he was four seconds in front of Nixon. Yamaha fans cheered, while Suzuki fans wept. But the whole thing was caused by absolute stupidity, and not by lack of reliability.

At Carlsbad, less than six months before, exactly the same thing happened to the same chassis and footpeg. Dick Hammer lost a race for no good reason. At that time the 250 racers were conceived in this country, and while frequently rapid, they often were a bit down on reliability. This year the 250s will be built in Hamamatsu, Japan, and almost assuredly will be leading contenders in the class that all but Yamaha have given up in, and for good reason. The Yamaha Twins have dominated the 250 class for more years than most of us can remember, usually taking eight of the 10 first places. Among those to admit defeat to Yamaha are: Harley-Davidson, Benelli, Ossa, Bultaco, Kawasaki, BSA, Triumph and Montesa. Completely aware of those who have fallen by the wayside, Suzuki will send three 250s to Daytona to complement the five 500s. I do not predict that the 250 Suzukis will beat the Yamahas, but they will be competitive and reliable; that is the Suzuki way.

Next year, if they decide to do it, Suzuki will not only be competitive, they will almost certainly be a contender for the winner's laurels.

Throughout a fabulous racing career Suzuki always has been able to select riders with the ability to tell them what is needed, and then go out with the best pilots and win races. That is exactly what has happened with the AMA road race plans. Ron Grant will continue as Suzuki's lead rider/technician. Ron's loyalty to Suzuki is difficult to match in this increasingly vicious Rat Race. Helping Ron will be his best friend, Art Baumann, who has been resting while Ron has been making a clean sweep of racing in New Zealand. Jimmy Odom again will be signed to ride a 500 at Daytona, and is a more than deserving recipient of the ride.

The shock news of the decade is that Jody Nicholas, certainly one of the six fastest riders in the world, will compete in both 250 and 500 classes. Jody's appearance on the Suzuki team comes after years of loyalty to BSA and Yamaha, and is typical of Suzuki's shrewdness in picking winners and amiable team riders. Ron, Art, Jimmy and Jody are four of the neatest guys in the whole world, and fall into the old racing adage that good guys go fast; bad guys never make it.

Joel Robert, Teamed With Geboers and Pettersson, Raved: "It Is The Best, Most Responsive Machine I've Ever Ridden."

DEVELOP THE PRODUCT—THEN BUY THE BEST

Completely in line with the strategy that led Suzuki to the very top in international road racing are the plans for world motocross competition. For not only did Suzuki start to take a serious interest in Daytona after the FIM's restrictive rulings, but also in professional motocross in Europe.

As ever before, Suzuki sent their top Japanese rider, Kasuo Kubo, off to Europe with a pair of bikes and a very observant manager named Ishikawa. A graduate of Michigan State and former European road race manager, it did not take IshikawaSan long to discover the faults of either the rider or the machine. And, after a winter back in Hamamatsu (a bad place to spend a winter), it was decided that Suzuki needed a European development rider. Ishikawa's research pointed towards Olle Pettersson, a Swede with more brains than speed, but not so slow.

Olle started a good season in 1968, but suffered a very bad break in his upper leg near mid season, and that was that. Ishikawa returned to Japan with a long face. Not only had Suzuki, because of a serious injury, lost its chance at European motocross, it also had not fared exceptionally well at Daytona.

ISHIKAWA-SAN

Fortunately Ishikawa smiles most of the time, and is not, by any stretch of the imagination, an unhappy man. Within weeks he was applying maximum energy towards new Daytona and international motocross machines. At the end of the season, when his leg was manageable, Pettersson was brought to Japan for "research riding." The result was that in 1969, Olle, despite a still sore leg, was 3rd in the World Championship.

As in the past, Ishikawa conferred at length with Pettersson and after long deliberation it was decided that Suzuki was ready. It was time to sign the two men who beat Pettersson: Joel Robert and Sylvain Geboers, CZ's top 250-cc motocross riders.

In late January the Belgians flew to Japan for a week of testing, with plenty of time to change the machines before the grand prix season. The stocky 26-year-old Joel, who has won three 250 world championships, was in a much more serious mood than when competing in the Inter-Am series. On the machine for the very first time, he tweaked the throttle as he approached a jump, and promptly looped the bike. While there were no injuries, the incident had a settling effect for a few days, and instilled considerable respect for the very light machine. Geboers, now 24 years old, did not sign with CZ until 1968. Previously he has ridden BSA, Matchless, Linstrome, Maico and Métissé in motocross during his eight-year racing career. Probably due to the wide variety of machines he has ridden, Geboers adapted very quickly to the 193-lb. racer.

The 250 Suzuki motocross, termed the RH 70, is almost identical to last year's machine. The frame, as on the road racers, is built from thin wall mild construction steel, and weighs about 16 lb. Swinging arm assemblies are quite unusual in that they are fabricated from aluminum sheet and tubing. The RN 70, which is the 370-cc version, features a steel swinging arm and slightly heavier tubing in the main cradle. Front forks are of Japanese manufacture, similar in construction to Cerianis with 6.5 in. of travel.

Both versions have a small 5-in. conical front hub. The rear hub is a 6-in., full width unit. Single leading shoe assemblies are used at both ends. Last year the fenders were aluminum, but now are molded plastic. The aluminum gasoline tank has been retained for this season. Footpegs are not spring loaded, but are permitted to fold only 45 degrees. Robert insisted on folding pegs because of the several serious lower leg injuries he has received during his career.

The small detail work throughout is typical of a Japanese factory racer. Great pains have been taken to ensure that nothing is too heavy, while at the same time being strong and functional. An example is that the rear spring/damper units are retained on the shafts by snap clips, rather than the usual practice of using a nut.

The engines also are typical of low production factory racing models. Sand castings are used generously and a good number are magnesium. At least six more pounds will be pared from the overall weight, through the use of even more magnesium components, before the machines go to Europe.

Both versions of the engine utilize the same crankcase/transmission castings. The 30-horsepower 250 has a five-speed transmission. But, in order to handle the 38 horsepower from the 370-cc engine, the gears have been widened and reduced to a four-speed cluster in the RN 70. A six-plate wet clutch is fitted to the 250, and a seven-plate unit to the 370 model. Otherwise the machines are almost identical. Both appear to feel the same when the rear end is lifted—very light.

Riding the machine is strange at first, due to the instant throttle response and very low weight. The engine runs very clean and completely vibration free up to the 7000-rpm maximum.

Most unusual, at first, is the high pitched exhaust note from the road race-type expansion chamber. The pipe has the largest center section and the smallest diameter stinger of any motocross contender, an arrangement that might indicate a

peaky engine. That is not the case, however, and even at 4000 rpm, the 250 has a healthy 9 horsepower. At no point in the rev band does the engine pick up revs quickly, and tractibility is excellent for such a light machine.

Hard riding tests were carried out at Fuji Speedway on a very cold and windy Sunday. The Speedway is located in the foothills of Mount Fuji, at an elevation of 2000 ft., and the beautiful mountain was covered with snow almost down to our level. After each riding and picture taking stint we would huddle around the burning car tires, thoughtfully hauled up by the mechanics.

Robert was doing about 15 minutes each time out without showing fatigue. Normally at this point in the off-season he can only manage five to ten minutes of hard going. He attributes his extra stamina to the light weight of the machine, and feels he will be fresher at the end of the long 45-minute races in Europe than his competitors on heavier machines.

The Fuji motocross circuit is bumpy. Robert, in fact, feels that it can be matched for bumps only by a few of the courses in Belgium. One section of about 200 yards has a series of foot-deep ripples, quite close together. It was through this section that Robert and Geboers were really outstanding. The machines maintained an amazingly straight line, again due to light weight, plus correct suspension.

Shy, modest Geboers, usually very conservative in his estimation of any machine, was ecstatic about both the 250 and 370 models. He feels it is the best machine he has ever ridden. Both riders are confident of success. Robert feels that only injuries can keep them from maintaining the first three places they now hold in the championship table.

The only concern on the part of Robert is the possible difficulty in handling on muddy, greasy circuits. The high power and light weight will call for an entirely different riding style and the use of higher gear ratios than current motocross machinery.

Despite rumors of Pettersson riding the 370 while Robert and Geboers chase the 250 title, all three will ride the 250 class. The bigger model will be riden by all three riders in international events that do not conflict with 250 title races.

Heading up the team will be Ishikawa, who has spent most of the last two years with Pettersson, and also was racing manager during Suzuki's great years in road racing. When asked if Suzuki could take the title, Ishikawa replied, "Without fail." The answer sounded very much like Ford Motor Company's a few years ago when they said they would win Le Mans, and did. Ishikawa is most anxious to bring the riders to this year's Inter-Am. U.S. Suzuki already has made application to Edison Dye, promoter of the series.

Can Suzuki pull off both racing projects? Only time will tell. Both the motocross and road race machines have proven to be extremely reliable. As Jody Nicholas will team with Ron Grant and Art Baumann for road races, Suzuki now has three of the best six pavement specialists in the country. All three riders are noted for being kind to the machines, as well as fast. A similar situation exists in motocross where Robert, perhaps the hardest charging rider in the world, has a good reliability record. Geboers offers a good contrast with his smooth, unflurried style. It is difficult to see how fast he is going until you see him running with Robert, and keeping pace. Pettersson, like the other two, is extremely kind to his machinery.

It is evident that Suzuki did some very careful planning. Not only have they taken good care of the engineering side of racing, their choice of racing personnel has been nothing less than astute, and well timed.

Only the coming season will prove them right. But both suits—road racing and motocross—are well covered.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

April 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1970 -

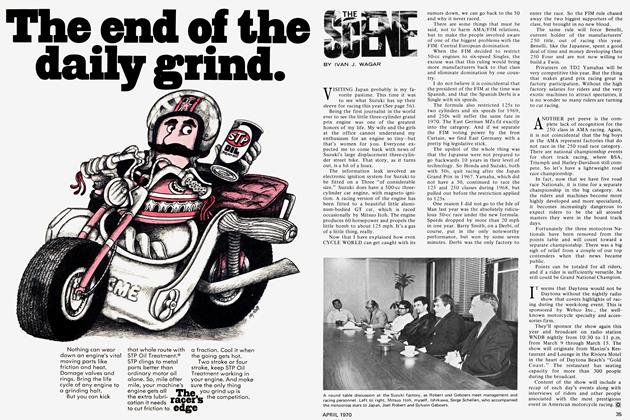

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

April 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

April 1970 By John Dunn -

Features

FeaturesA Mind of Its Own

April 1970 By Bob Ebeling -

Features

FeaturesHistory of Royal Enifield

April 1970 By Geoffrey Wood