HISTORY OF Royal Enifield

GEOFFREY WOOD

This Venerable Producer of Powerful English Road Burners Pioneered Many Valuable Concepts in Motorcycling Technology.

ENGLAND is by nature a rather conservative country, yet its people often have, by the dint of sound thinking and dedication to a goal (and a paradoxical bent for creative tinkering — Ed.), achieved some noteworthy and classic results. This is especially true in the manufacturing of motorcycles, where their design innovation down through the years has been sound and progressive, while at the same time a respect for the past has been maintained that has created great legends of nostalgic proportions.

Typical of this philosophy of progress tempered by tradition is Royal Enfield — a Redditch concern that has an impressive record in both design innovation and competition results. The history of Royal Enfield does not, however, contain any dramatic successess on the world's classical road racing courses, for the company has nearly always chosen to proceed in other directions. The history does contain many splendid "firsts" in design improvement, and the marque's record in trials competition is both outstanding and colorful.

The story of this typically English business began in 1892 when the Enfield Manufacturing Company was established in Hunt End, a village near Redditch. The product at that time was bicycles, which has been a popular way for many concerns to get started in motorbike production. The name of the infant business was changed to Enfield Cycle Company in 1896, and the first motorcycle was produced in 1898.

This first motorbike was a spindly looking affair, with a tiny engine mounted on the front fork that drove the rear wheel by a belt. The engine featured the inlet-over-exhaust-valve design — the exhaust valve was opened and closed by a cam, the inlet valve sucked open by the piston on its down stroke. This primitive engine produced about .75 bhp, and pedals were needed for starting and for aid on hills. There was no method of disengaging the engine on this model, since clutches were not in general use then, and neither wheel had any suspension.

It was not a particularly good design, even for those early days, so in 1902 a new model with the engine mounted centrally in the frame was introduced. This model was also less than impressive in sales volume, and for a while it looked as though the company wasn't going far in the motorcycle field. An interesting innovation was made in 1906, however, when a high-tension magneto was used. This device provided more reliable sparking than the previous battery-coil ignition, which was notoriously unreliable.

The fortunes of Royal Enfield finally turned upward in 1910 when the management really got down to the designing of a good motorcycle. With this effort came the concern's first attempt at racing, which was a popular approach in those days for the purpose of obtaining advertising prestige. The result was a 5th place in the 1911 Isle of Man Junior TT, which made the name better known to the public.

Since 1898 Royal Enfield motorcycles had used engines made by another "proprietary" company, at that time a common practice in Europe. As this approach seemed to be unsatisfactory, in 1912 the Enfield firm began building its own engines. The first was a 340-cc V-twin with a bore and stroke of 54 by 74 mm. This design proved so dependable that almost overnight the Enfield became one of the leading English makes.

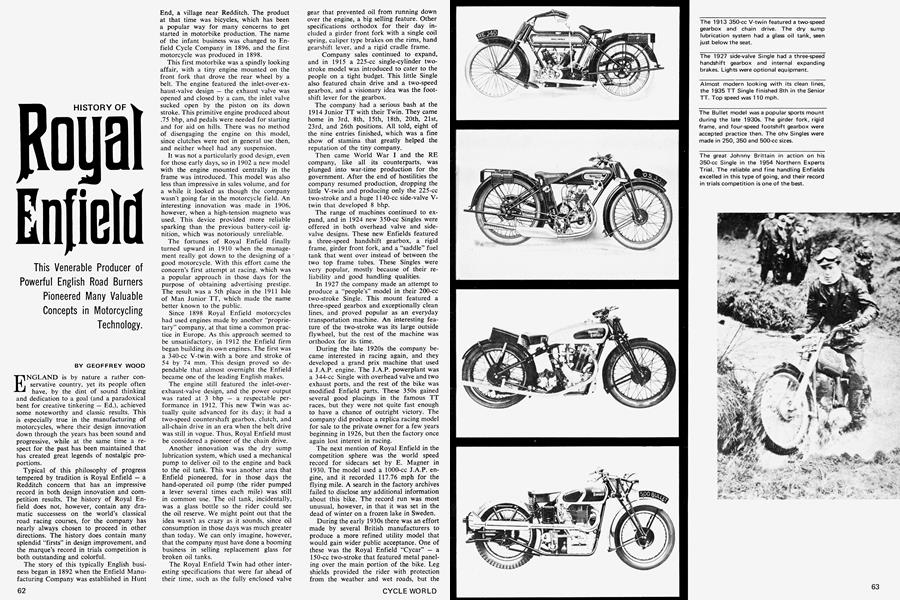

The engine still featured the inlet-overexhaust-valve design, and the power output was rated at 3 bhp — a respectable performance in 1912. This new Twin was actually quite advanced for its day; it had a two-speed countershaft gearbox, clutch, and all-chain drive in an era when the belt drive was still in vogue. Thus, Royal Enfield must be considered a pioneer of the chain drive.

Another innovation was the dry sump lubrication system, which used a mechanical pump to deliver oil to the engine and back to the oil tank. This was another area that Enfield pioneered, for in those days the hand-operated oil pump (the rider pumped a lever several times each mile) was still in common use. The oil tank, incidentally, was a glass bottle so the rider could see the oil reserve. We might point out that the idea wasn't as crazy as it sounds, since oil consumption in those days was much greater than today. We can only imagine, however, that the company must have done a booming business in selling replacement glass for broken oil tanks.

The Royal Enfield Twin had other interesting specifications that were far ahead of their time, such as the fully enclosed valve gear that prevented oil from running down over the engine, a big selling feature. Other specifications orthodox for their day included a girder front fork with a single coil spring, caliper type brakes on the rims, hand gearshift lever, and a rigid cradle frame.

Company sales continued to expand, and in 1915 a 225-cc single-cylinder twostroke model was introduced to cater to the people on a tight budget. This little Single also featured chain drive and a two-speed gearbox, and a visionary idea was the footshift lever for the gearbox.

The company had a serious bash at the 1914 Junior TT with their Twin. They came home in 3rd, 8th, 15th, 18th, 20th, 21st, 23rd, and 26th positions. All told, eight of the nine entries finished, which was a fine show of stamina that greatly helped the reputation of the tiny company.

Then came World War I and the RE company, like all its counterparts, was plunged into war-time production for the government. After the end of hostilities the company resumed production, dropping the little V-twin and producing only the 225-cc two-stroke and a huge 1140-cc side-valve Vtwin that developed 8 bhp.

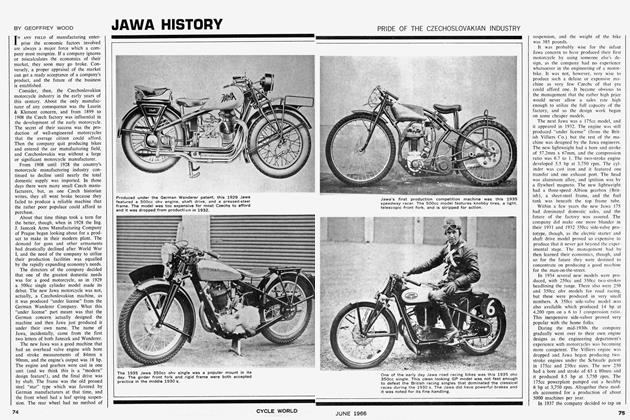

The range of machines continued to expand, and in 1924 new 350-cc Singles were offered in both overhead valve and sidevalve designs. These new Enfields featured a three-speed handshift gearbox, a rigid frame, girder front fork, and a "saddle" fuel tank that went over instead of between the two top frame tubes. These Singles were very popular, mostly because of their reliability and good handling qualities.

In 1927 the company made an attempt to produce a "people's" model in their 200-cc two-stroke Single. This mount featured a three-speed gearbox and exceptionally clean lines, and proved popular as an everyday transportation machine. An interesting feature of the two-stroke was its large outside flywheel, but the rest of the machine was orthodox for its time.

During the late 1920s the company became interested in racing again, and they developed a grand prix machine that used a J.A.P. engine. The J.A.P. powerplant was a 344-cc Single with overhead valve and two exhaust ports, and the rest of the bike was modified Enfield parts. These 350s gained several good placings in the famous TT races, but they were not quite fast enough to have a chance of outright victory. The company did produce a replica racing model for sale to the private owner for a few years beginning in 1926, but then the factory once again lost interest in racing.

The next mention of Royal Enfield in the competition sphere was the world speed record for sidecars set by E. Magner in 1930. The model used a 1000-cc J.A.P. engine, and it recorded 117.76 mph for the flying mile. A search in the factory archives failed to disclose any additional information about this bike. The record run was most unusual, however, in that it was set in the dead of winter on a frozen lake in Sweden.

During the early 1930s there was an effort made by several British manufacturers to produce a more refined utility model that would gain wider public acceptance. One of these was the Royal Enfield "Cycar" — a 150-cc two-stroke that featured metal paneling over the main portion of the bike. Leg shields provided the rider with protection from the weather and wet roads, but the model never caught the public's fancy and it was soon dropped.

British motorcycles became more sophisticated during the early 1930s, with improvements in performance, appearance and reliability. Royal Enfield designers were very progressive during those years, and a new range of Singles became very popular. These were produced in 250, 350 and 500-cc sizes, and the purchaser had the choice of side-valve or overhead valve powerplants. A new four-speed footshift gearbox was available, while the hand clutch had by then replaced the foot clutch. Another feature was the oil tank being contained in the crankcase — a move to lower the center of gravity and thus improve the handling as well as making for a cleaner looking and running bike due to the absence of oil lines.

During the middle 1930s the road racing sport developed into a magnificent international spectacle with hundreds of thousands of spectators. A good showing in these events brought a company great prestige and often an increase in sales, so it was not surprising that Royal Enfield once again became interested in the TT.

The first machines were entered in the 1934 Senior TT, and they were an interesting model as well as being a fascinating chapter in the history of the company. The powerplant was developed from the company's standard 500-cc pushrod Single, and it had a bore and stroke of 86 by 86 mm. The head, however, was totally different, being a parallel four-valve unit cast in bronze. A single 1-3/32-in. TT carburetor was used, and the engine was canted slightly forward in the frame — a common practice in the early 1930s.

An unusual feature of the TT model was the alloy con-rod with its plain floating Duralumin bushing for a big end bearing, which was used instead of the more normal roller bearing. This bearing needed a plentiful supply of oil and a large clearance. This made for ample mechanical noise and a strong smell of castor oil. The problem was eventually solved by replacing the Duralumin bushing with one of steel which was faced on both sides with white metal. This bearing could be run at a closer tolerance and proved to be eminently satisfactory.

The rest of the bike was quite conventional for 1935. A rigid cradle frame was used in conjunction with a girder front fork, and a four-speed Albion close-ratio gearbox was mounted behind the engine. The brakes were large steel drum affairs that had fins but no air scoops for cooling, and the alloy fuel tank had a long classical shape. The top end was claimed to be 110 rnph. which was good but not quite good enough for 1935. C.S. Barrow brought this model into 8th place in the 1935 Senior TT, but then the company once again lost interest in racing.

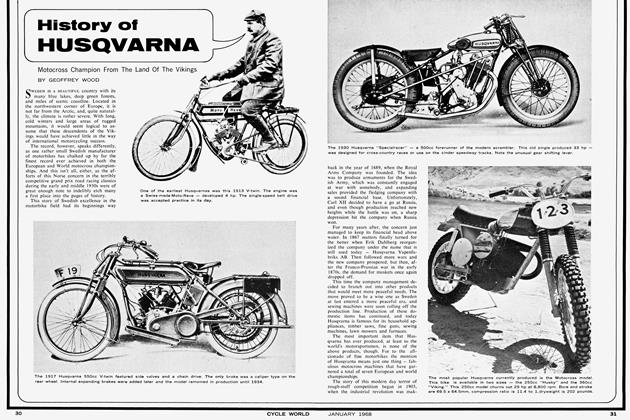

During the late 1930s, observed trials developed into a leading attraction, and Royal Enfield decided to pursue this field by introducing the "Bullet" models. These were splendid motorcycles for the fellow who needed an everyday transportation mount but who also wanted to compete in weekend trials. The 250-cc (64 by 77 mm), 350-cc (70 by 90 mm), and 500-cc Bullets used the same engine as the standard models, but modifications were made to cams and compression ratio to pep up performance. The greatest difference was in the chassis parts, with upswept exhaust, narrow fenders, wideratio gear boxes, quickly detachable lights, and several tire sizes and types all being available.

These Bullet models became very popular with the more sporting minded riders, and the factory even went so far as to sponsor a works team for trials events. During the 1937 and 1938 seasons the Bullet overwhelmed its opposition, and it became known as an exceptionally fine handling trials bike.

Aided by all this publicity from the trials game, the sales continued to expand during the last years before World War II. One noteworthy innovation in 1939 was the adoption of the plain con-rod big-end bearing on all the Singles, which was a benefit of the knowledge gained from the colorful TT racer.

Then came World War II and once again the Royal Enfield plant w;as turned over to W.D. production. After the war the company brought out a tiny 125-cc two-stroke and the 350-cc model "G." The 21-incher featured a new hydraulically dampened telescopic front fork. These utility models were continued for several years and helped get England rolling again, and the export market was exploited all over the world.

By 1949 the economy had developed to the point where more luxury could be permitted, and the factory came out wjth a new 500-cc Twin as well as a swinging arm frame for both the ohv models. This use of the now accepted swinging arm design was not the first, of course, but it was one of the first and was well ahead of most of the other larger British manufacturers.

The new Twin had a bore and stroke of 64 by 77 mm, and it produced 25 bhp at 5500 rpm. This Twin was subsequently developed into a 700-cc size (Meteor) and then to the 750-cc Interceptor in 1963. The Singles were also developed, with a 500-cc model added to the range in the early 1950s and the 250-cc unit-construction model in the early 1960s. The 350-cc Bullet was also changed to the unit-construction design, but then the 500-cc model was dropped. The company also produced a pair of 250-cc Twins during the 1960s, and these models had Villiers two-stroke power plants. An interesting model in 1965 was the ohv 250-cc "Continental GT" — an 85-mph speedster set up to look much like a road racer complete with racing windscreen and five-speed gearbox Another innovation was the availability of two streamlined fairings — a move to make the bikes more comfortable at cruising speeds.

The Singles, however, failed to maintain a brisk sales pace, so in 1967 the range was reduced to only the big 750-cc model The Royal Enfield Company also ran into financial problems then, and the rights to production have recently been acquired by the Enfield Precision Ltd. concern. This passing of the Single was lamented by many, since the reputation for fine handling and stamina had gained many friends all over the world. This was true even in America, where the Enfield has won many cross-country and trials events, such as Eddie Mulder's trouncing of the Big Bear field when he was only a 16-year-old kid. The Enfield, incidentally, was imported into this country from 1955 through 1959 with "Indian" on the fuel tank. And then lastly, there is the fantastic record in flat track racing that has been racked up

by Elliott Shultz and others on their 500-cc Singles.

There are, however, two final chapters in the Royal Enfield story that hold great intrigue for aficionados of the sport. One effort was the 1964-1966 road racing model, which was promising but not overly successful; and the other chapter was the trials models, which were both colorful and fabulously successful.

The racing bike was a 250-cc two-stroke Single with an Alpha crankcase and Herman Meier-designed upper half. Operating on a 10:1 compression ratio, the engine turned to 8500 rpm and pumped out 34 bhp. This model was put into production for the 1965 and 1966 seasons, and by then it sported a huge 1.5-in. GP carburetor.

The racer's gearbox was an Albion fivespeed unit, and the frame was a twin loop type with an orthodox swinging arm suspension. The front fork was a Reynolds leading-link type, and an Enfield front brake was used with an Oldani rear brake. The tire sizes were 2.75-18 and 3.25-18, and fiberglass was used for the seven-gallon fuel tank and fairing. These racers proved to be reasonably fast, but neither the works riders nor the private owners achieved any remarkable results. Many observers felt that the Single had great potential, but that not enough genuine effort was put behind the project.

The "dirt" chapter of the Enfield was more successful, and for this we must go back to 1950 when the company began producing trials and scrambles models for the private owner as well as sponsoring a works team. The 350-cc Bullet was the basis for development, and it was eminently suitable for trials use due to its low center of gravity and excellent low speed power. Operating on a 6.5:1 compression ratio, the engine developed 18 bhp at 5750 rpm.

The main changes were to the chassis parts, with 2.75-21-inch and 4.00-19-in. front and rear "trials" tires being used. The exhaust pipe was upswept, alloy fenders fitted, the footpegs placed higher and farther back, and handlebars were wider. With its wide ratio gearbox and swinging arm frame, this model was a superb "bog wheel," and it was thrown into competition with the best. In the early 1950's all other marques used a rigid frame for their trials bikes, since the belief was that rear springing would cause too much hopping about and handling would suffer. The Royal Enfield riders proved differently, and within a few years the others began to use spring frames on their trials bikes.

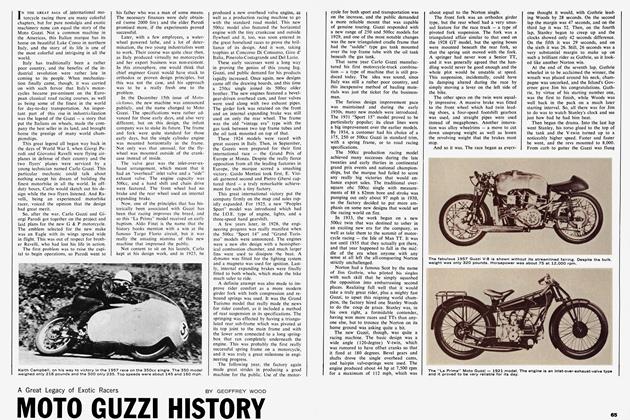

The No. 1 Enfield rider then was a tall youngster named Johnny Brittain, and this fellow racked up a classic number of wins before he retired in 1965. Johnny first began to win the big national trials in 1953 when he came home 3rd in the championship table, and for the next few years he battled with the top AJS and BSA stars.

The great day finally arrived in 1957 when Brittain won the coveted British Trials Riders Championship, still using his trusty 350-cc Bullet that had been developed to an exceptionally fine pitch by many small but important modifications. By then the Enfield had become especially popular with the private owners, and all of the major European trials events had the beautiful Singles plonking over the hills and dales in classic trials stance.

Probably the finest achievement in the company's history occurred in May of 1957, when John won the Premier Trophy in the Scottish Six Days Trial. Many observers felt that Brittain's performance in the highlands was one of the very greatest, and it was a fitting climax to many years of outstanding performances by both Brittain and the marque in this classic of trials events. After 1957 Johnny faded from the scene a bit, which was due both to the likes of Gordon Jackson (350-cc AJS) and Sammy Miller (500 Ariel) plus having to concentrate more on the growing RE dealership he had in Bloxwich.

The company decided that this outstanding trials record justified producing a genuine Replica model for the private owner, and in 1958 it was duly offered for sale. These were magnificent trials bikes for the serious competitor, being genuine "works replicas" and not just standard production trials models.

The engine was still the basic 350-cc Bullet, but an alloy cylinder and head shed weight and improved the heat dissipation. The compression ratio was 7.25:1, and extra heavy flywheels were used to improve the low speed pulling power. Carburetion was

by a small 15/16-in. Amal unit, and a special exhaust pipe was used that tucked in behind the rear frame piece. The gearbox had wide ratios of 7.56, 10.58, 16.25, and 22.68:1, and other gear sets were available. The purchaser also received extra sprockets so that he could gear the bike to suit the event.

The frame for the replica model was special, being a lightweight unit made from chrome-molybdenum tubing. Small alloy fenders were used, and a solo seat and high footpegs were fitted. The brakes were small units — 7-in. rear and 6-in. front, and a narrow 2.5-gallon fuel tank was used. The ground clearance on the Single was 8-in., and the dry weight was only 309 lb. These replica models were superb trials bikes, and in the hands of private owners they established an enviable reputation.

A few years later, in 1962, the works team showed up in the Scottish event with a 250cc model, which had been developed from the unit-construction Single. The showing by the four works riders was very good, but not quite first class. Then the interest in trials waned a bit, no doubt caused by both the trend to lightweight two-strokes and the fact that the company was experiencing financial troubles. Notable showings were made by Peter Fletcher in the 1965 and 1966 events, when he scored a 10th and an 8th place on his big 500-cc model. These performances earned Peter the award for the best "over 350-cc" performance, which was a fitting tribute to the marque that had done so much to develop the classical single-cylinder trials bike.

For the present, Royal Enfield aficionados must be content with the big Interceptor Twin, which is a genuine 120-mph road burner that few others can out perform. Something has been lost in the passing of the superb handling Singles, though, and it is in these thumpers that the real legend of the Royal Enfield lives on. For it was in the rocky highlands of the Scottish Trial that the marque carried on its quiet manner of research, and the result was a fine Single in an era when thumping exhausts were the mark of distinction.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

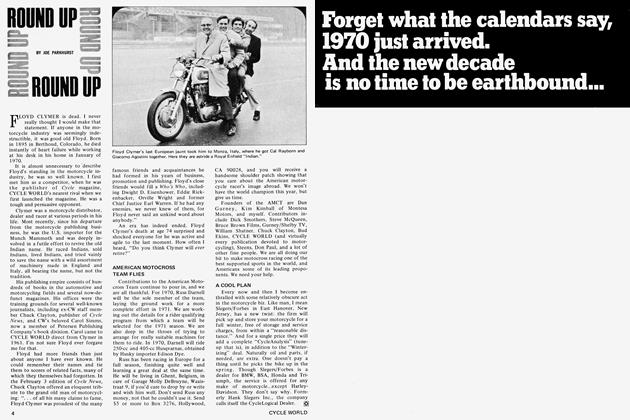

DepartmentsRound Up

April 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

April 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

April 1970 By John Dunn -

Features

FeaturesA Mind of Its Own

April 1970 By Bob Ebeling -

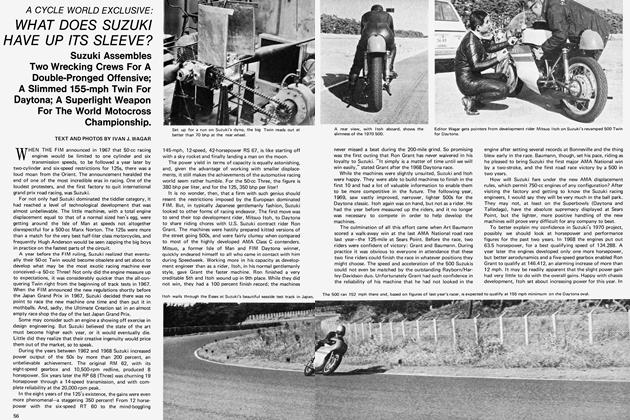

A Cycle World Exclusive

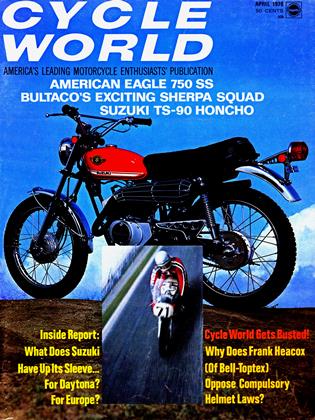

A Cycle World ExclusiveWhat Does Suzuki Have Up Its Sleeve?

April 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar