JAWA HISTORY

GEOFFREY WOOD

IN ANY FIELD of manufacturing enterprise the economic factors involved are always a major force which a company must recognize. If a company ignores or miscalculates the economics of their market, they soon may go broke. Conversely, a proper appraisal of the market can get a ready acceptance of a company’s product, and the future of the business is established.

Consider, then, the Czechoslovakian motorcycle industry in the early years of this century. About the only manufacturer of any consequence was the Laurin & Klement concern, and from 1899 to 1908 the Czech factory was influential in the development of the early motorcycle. The secret of their success was the production of well-engineered motorcycles that the average citizen could afford. Then the company quit producing bikes and entered the car manufacturing field, and Czechoslovakia was without a large or significant motorcycle manufacturer.

From 1908 until 1928 the country’s motorcycle manufacturing industry continued to decline until nearly the total domestic supply was imported. In those days there were many small Czech manufacturers, but, as one Czech historian writes, they all went broke because they failed to produce a reliable machine that the rather poor populace could afford to purchase.

About that time things took a turn for the better, though, when in 1928 the Ing. J. Janecek Arms Manufacturing Company of Prague began looking about for a product to make in their modern plant. The demand for guns and other armaments had drastically declined after World War I, and the need of the company to utilize their production facilities was equalled by the rapidly expanding economy’s needs.

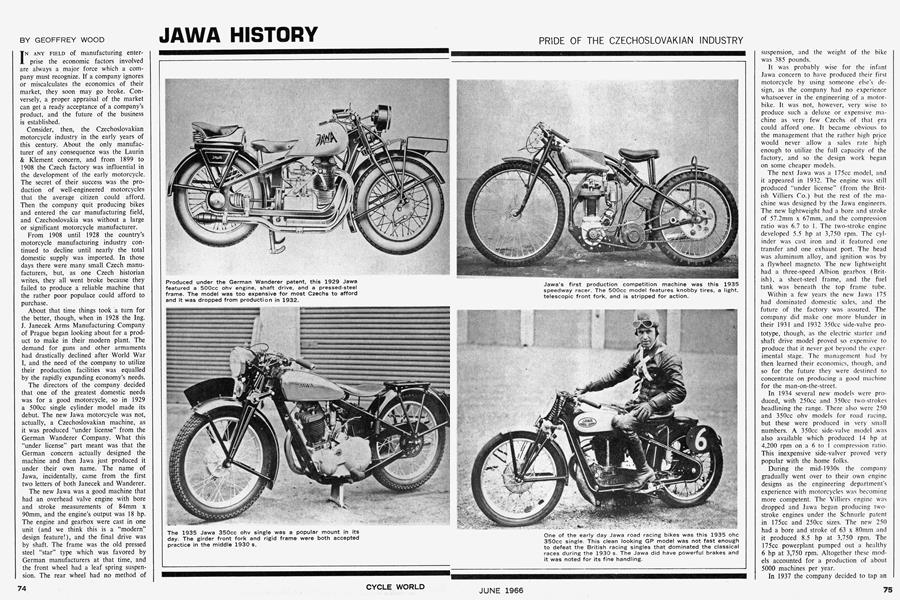

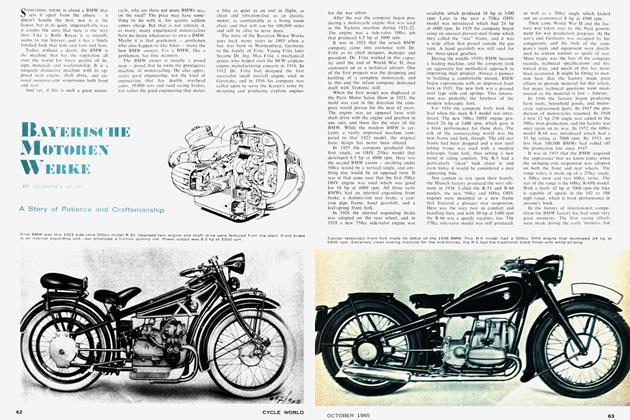

The directors of the company decided that one of the greatest domestic needs was for a good motorcycle, so in 1929 a 500cc single cylinder model made its debut. The new Jawa motorcycle was not, actually, a Czechoslovakian machine, as it was produced “under license” from the German Wanderer Company. What this “under license” part meant was that the German concern actually designed the machine and then Jawa just produced it under their own name. The name of Jawa, incidentally, came from the first two letters of both Janecek and Wanderer.

The new Jawa was a good machine that had an overhead valve engine with bore and stroke measurements of 84mm x 90mm, and the engine’s output was 18 hp. The engine and gearbox were cast in one unit (and we think this is a “modern” design feature!), and the final drive was by shaft. The frame was the old pressed steel “star” type which was favored by German manufacturers at that time, and the front wheel had a leaf spring suspension. The rear wheel had no method of suspension, and the weight of the bike was 385 pounds.

PRIDE OF THE CZECHOSLOVAKIAN INDUSTRY

It was probably wise for the infant Jawa concern to have produced their first motorcycle by using someone else's design, as the company had no experience whatsoever in the engineering of a motorbike. It was not, however, very wise to produce such a deluxe or expensive machine as very few Czechs of that era could afford one. It became obvious to the management that the rather high price would never allow a sales rate high enough to utilize the full capacity of the factory, and so the design work began on some cheaper models.

The next Jawa was a 175cc model, and it appeared in 1932. The engine was still produced “under license” (from the British Villiers Co.) but the rest of the machine was designed by the Jawa engineers. The new lightweight had a bore and stroke of 57.2mm x 67mm, and the compression ratio was 6.7 to 1. The two-stroke engine developed 5.5 hp at 3,750 rpm. The cylinder was cast iron and it featured one transfer and one exhaust port. The head was aluminum alloy, and ignition was by a flywheel magneto. The new lightweight had a three-speed Albion gearbox (British), a sheet-steel frame, and the fuel tank was beneath the top frame tube.

Within a few years the new Jawa 175 had dominated domestic sales, and the future of the factory was assured. The company did make one more blunder in their 1931 and 1932 350cc side-valve prototype, though, as the electric starter and shaft drive model proved so expensive to produce that it never got beyond the experimental stage. The management had by then learned their economics, though, and so for the future they were destined to concentrate on producing a good machine for the man-on-the-street.

In 1934 several new models were produced, with 250cc and 350cc two-strokes headlining the range. There also were 250 and 350cc ohv models for road racing, but these were produced in very small numbers. A 350cc side-valve model .was also available which produced 14 hp at 4,200 rpm on a 6 to 1 compression ratio. This inexpensive side-valver proved very popular with the home folks.

During the mid-1930s the company gradually went over to their own engine designs as the engineering department’s experience with motorcycles was becoming more competent. The Villiers engine was dropped and Jawa began producing twostroke engines under the Schnurle patent in 175cc and 250cc sizes. The new 250 had a bore and stroke of 63 x 80mm and it produced 8.5 hp at 3,750 rpm. The 175cc powerplant pumped out a healthy 6 hp at 3,750 rpm. Altogether these models accounted for a production of about 5000 machines per year.

In 1937 the company decided to tap an even greater market when they produced the lOOcc “Robot” model. The new Jawa featured a 2.7 hp engine that was mounted in a pressed-steel frame. A set of pedals was also fitted for starting and assistance on steep hills, and this motorized bicycle was priced so cheaply that almost everyone in Czechoslovakia could afford one. This Robot model was a smashing success, and many thousands of citizens climbed off their bicycles and onto a Robot.

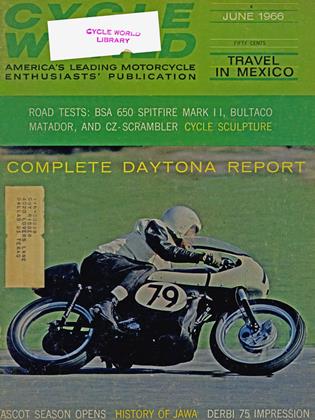

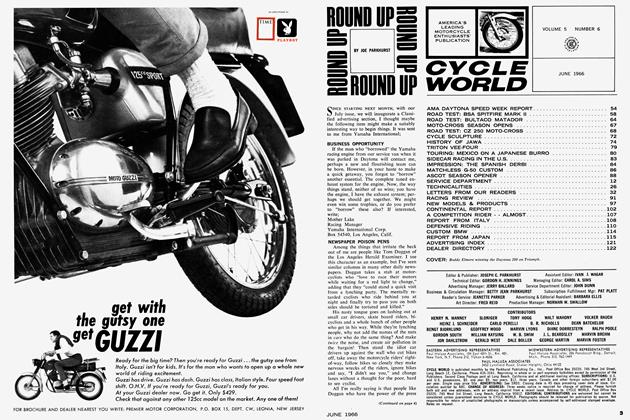

During the late 1930s the factory became more sporting conscious and several attempts were made at producing competition machines. Probably the most noteworthy was the production of special 350 and 500cc ohv speedway or “short-track” racing models. The Jawa Company also made available a parts kit to convert the 350cc side-valve model into an overhead camshaft unit, and then later a complete ohc 350 single was available for road racing. The factory even went so far as to enter a team in the famed Isle of Man TT races in 1932, ’33 and ’35; best performances were an eighth and a twelfth in the 1933 Senior.

Then the country became involved in World War II and the factory was mobilized for military production. Despite the war effort, the Jawa engineering department spent a great deal of time and effort in designing some new machines for peace-time production. Working secretly in a remote store, the Czech designers drew up their plans for a new Jawa that would be competitive in the world market. Previously, the marque had been strictly a home-country product as the Jawa was not a well enough engineered machine to compete in the world market.

In the spring of 1946 the new Jawa was unveiled at the Paris show — and the worldwide response was tremendous. Designed by the engineers J. Josif and J. Krivka, the new Jawa was termed to be ten years ahead of its time by several prominent journalists of the day.

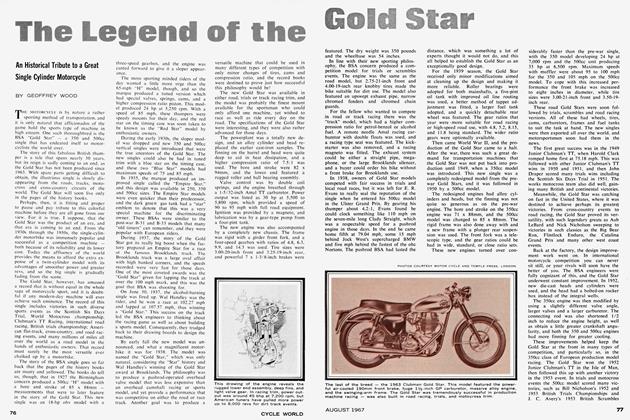

The obvious theme of the new model was comfort and styling. The 250cc twostroke engine had a bore and stroke of 67 x 75mm, and the engine and fourspeed gearbox were both in one cleanlooking case. The frame was a rugged square-tubed affair that had a good “plunger” rear suspension system. The front had a hydraulically dampened telescopic fork with a generous amount of travel. Then, for some frosting on the cake, the seat had a special torsion spring mounting that gave an extra degree of comfort.

The brilliant engineering did not end with the frame, though, as the gearshift had an “automatic” clutch that enabled the rider to shift gears once underway by just using the footshift lever. The headlight was contained in a streamlined nacelle, and the general appearance of the machine was sleek and smooth.

Probably the most noteworthy feature, though, was the smooth and comfortable ride. This was really remarkable on such a cheaply priced machine, considering the fact that most of the world’s motorcycles were still using rigid frames.

The 250 model was augmented by a new 350cc “Ogar” twin the following year, and these two models were marketed all over the world. The fast growing sales and acceptance of these new Jawas were all it took for the company to expand its horizons, and so in 1951 an exciting new 500cc ohc twin was added to the range. This new twin was too expensive for the majority of riders, but it nevertheless was popular in eastern Europe as a sporting roadster.

The new twin looked very much like the other Jawa models, except it was larger and had the ohc engine with measurements of 65 x 73.6mm, and the compression was left very low at 6.8 to 1 for the dreadful gasoline that was available then. The engine had a single camshaft which actuated short rockers. The 500 twin proved to be expensive and it remained in production for only a short time, but some private owners did modify and race them with a fair amount of success.

The next Jawa milestone was in 1954 when they changed from the plunger type of rear suspension to the popular swinging-arm system. With only minor detailed improvements since then, the Jawa line remains much the same today. The basis of the current range are the 250cc and 350cc single cylinder two-strokes with measurements of 65 x 75mm and 76 x 75mm respectively. The Jawa can be had today in a variety of models including road, moto-cross, and trials trim. All models feature the rugged engine and gearbox in one case, two exhaust ports and pipes, and the “automatic” clutch.

The present day Jawa is a highly respected motorcycle all over the world for its quality of finish, fine handling, and reliability. While the engine in its present stage of tune is not producing quite as much power as some of its competitors, its smooth delivery and wide spread of torque often makes it a more desirable machine for the rider of average ability.

In the sporting sphere of motorcycling the Jawa has had some truly great moments. While the marque could not be considered as being one of the giants of the international competition scene, its record is nonetheless impressive. The only problem in examining the technical features of Jawa’s racing history is the great secrecy that has surrounded their efforts since the mid-thirties. A typical Jawa tactic is to throw a cover over their mount after a Grand Prix and hustle it back to Czechoslovakia — talking to no one in the process.

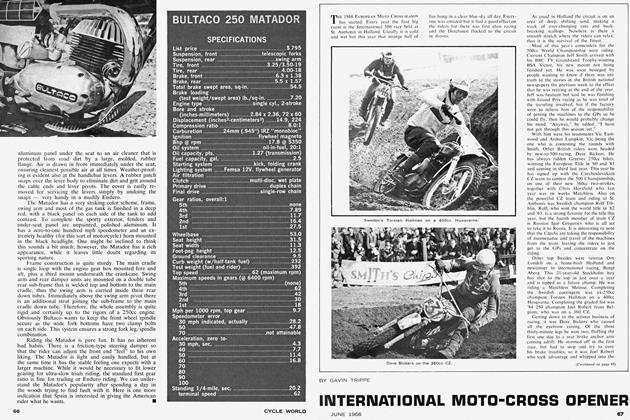

The type of competition that has probably been the most rewarding to the company has been moto-cross racing. Jawa produces several machines specifically for moto-cross such as the 250 and 350cc two-stroke models and the 500cc ohv Eso. This later mount is produced by a branch company that sells four-stroke engined machines for competition only.

The most noteworthy achievement in scrambling was obtained by Jaromir Cizek in 1958 when he won the very first of the 250cc Coupe d’ Europe Moto-Cross Championships. Cizek’s Jawa was a special “works” model that the factory had “breathed” on, and its performance was somewhat more devastating than the standard production model.

The following year Cizek could get no higher than third place in the championship standings, as Rolf Tibblin’s Swedish Husqvarna was much lighter than the Jawa and therefore had better acceleration. Since then the Jawa has gradually faded away from the winner’s circle, and they have taken a greater interest in international trials.

The 500cc Eso has done well, also, but the factory has never made a really serious attempt with top-flight works riders. The Eso continues to be popular as a production scrambler, as its light weight of around 275 pounds plus a beefy 40 hp at 6500 rpm make it a fine handling machine with good acceleration.

One of the most interesting of the Jawa competition machines is the Eso speedway racer. The latest 500cc DT-6 model features an ohv engine with a bore and stroke of 88 x 82mm, and the engine churns out a mighty 50 hp at 8,000 rpm on straight alcohol. For specialized European short-track racing, a light rigid frame is used along with a tiny fuel tank, a total loss lubrication system (the oil just spills out on the track), and studded tires. While this Czech racer has yet to display any great superiority over the traditional British J.A.P. engine, it has been coming on strongly the past few years.

Racing to a European means road racing, particularly in the classical Grand Prix events, and Jawa has expended a modest amount of effort in this direction. It is rather odd, though, considering the fact that Jawa has primarily been a twostroke producer, that they have chosen the four-cycle engine for the bulk of their racing activities.

The marque’s serious racing program began back in the mid-1950s when they built up some 250 and 350cc twins for a works team. On these machines the venerable Frantisek Stastny has garnered many Czechoslovakian championships, and his record over the years in world championship racing is impressive. Franta has also been ably supported by Gustav Havel, and these two riders have brought a great deal of honor to both the sport and their country.

Franta’s first visit to the Isle of Man TT races was made in 1957 with a 250cc twin that had gained him many a Czech championship. The little twin had a fair turn of speed, too, being capable of something like 120 mph with a full “dustbin” fairing. The speed that year was about 15 to 20 mph down on the World Champion Mondials, though, and Stastny had to settle for a twelfth place.

After the race a British journalist tested many of the works TT bikes for a comparison, and he noted that the Jawa was one of the finest handling bikes he had ever ridden around the circuit. The massive 10 1/4" brakes (the front was a twin leading shoe unit) were said to be exceptionally powerful and fully up to the job of stopping the 310-pound twin. The engine’s 30 hp at 11,000 rpm was fed to a five-speed gearbox.

During the 1957 season Franta also garnered a fifth in the Dutch Grand Prix, but the following few years proved fruitless as the Jawa simply lacked the speed to be a winner. A great amount of development work was put into the twin and the engine was gradually expanded into a 350cc unit. In 1960 Franta appeared with a new and much lighter 350 model, and the horsepower had become great enough to trounce all but the MV Agusta Fours. In the French GP he took a second, and in the final event of the season on the fast Monza circuit he took another well-earned second place. This gave Franta enough points for a fourth place in the World Championship.

For 1961 the factory raced in the junior class almost exclusively, as the 250 model was a bit heavy and it lacked the speed to compete against the Honda fours. The best that a 250 Jawa did that year was a fifth in the Dutch event, with Stastny in the saddle.

In the 350cc class Franta had a good year, taking a fifth in the I.O.M., thirds in the Dutch and Ulster events, a second in the East German, and outright wins in the German and Swedish classics. In addition, teammate Gustav Havel took a second in both the German and Swedish events, a third at Monza, and a fourth in the East German G.P. For his efforts, Franta gained the runnerup position to the late Gary Hocking (MV) in the World Championship standings. This was and still is both Jawa’s and Stastny’s finest year.

The following year the marque did not fare as well; the other four-cylinder racers were getting faster and the Jawa was not. Franta took a fourth in the Dutch, a third in the I.O.M., and a second in the Ulster; and Havel captured a fifth in the Ulster. More speed was needed!

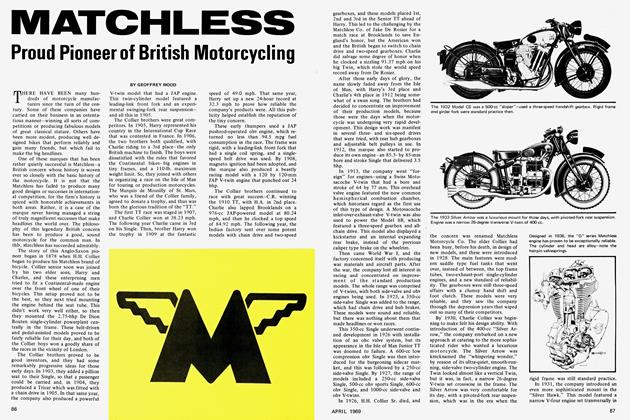

The factory racing department responded in 1963 with a new bike that has proven to be a very good racing machine. The engine is still a twin with a bore and stroke of 62 x 57.9mm, but the head is changed over to the four-valves-per-cylinder arrangement. The lighter valve gear allows higher revs, and the 350cc engine develops 52 hp at 11,500 rpm on a 10.5 to 1 compression ratio. Ignition is by coil to four spark plugs.

The higher-revving engine has a narrower power range, and so the five-speed gearbox has given way to a six-speed version. The frame is a tubular cradle type with a standard telescopic fork for the front wheel and a set of Girling suspension units on the rear swing-arms. The front tire is a 3.00 x 18 size, and the rear is a 3.50 x 18. Both brakes are a massive 200mm diameter, and the front brake a dual unit. The top speed of the 350 is approximately 150 mph, and the dry weight is a light 279 pounds.

During 1963 there were a lot of “bugs” to be worked out of the new design, and Jawa often failed to finish the race. Stastny garnered a third in the Junior TT plus a fourth in the Belgian, and that was about it for the new four-valver. Riding the older two-valve models Gustav Havel took a sixth in the Belgian, and fourths in the East German and German events; and P. Slavicek took a fifth at Monza.

During 1964 the works team did not fare too well, as the factory was improving the four-valve engine and the team had some rotten luck. Havel took a second place in the East German GP and a third in the Ulster for the only high notes of the year.

In 1965 the team made a great comeback. The marque even had a bash at the 250 class again with Stastny taking fifth places in both the I.O.M. and Monza events. On the bigger junior model Havel captured thirds in the Ulster, German, and East German classics. Stastny followed his teammate up with fourths in the East German and Monza events, and then Franta scored his popular last lap victory in the Ulster Grand Prix. This late season showing by Stastny was good enough to give him a tie for fifth place in the World Championship standings.

So this is the story of Jawa, the leader of the Czechoslovakian motorcycle industry. It is a splendid story of how a company has produced a really good and comfortable motorcycle for the everyday rider, while at the same time adding a distinctive flavor to the international sporting scene. Not having a really great sales volume, the Jawa factory has had to operate their racing program on a limited budget, but their contribution to our sport is still unique and colorful.

Someday, though, Frantisek Stastny shall have to retire, and when he does, a really great chapter in classical racing will be ended. Always faithful to his homeland products, Franta has established himself as one of the smoothest and most reliable men on the Grand Prix courses. He is also a terribly popular and highly respected man and, in fact, he is often referred to as the most beloved racing man in all of Europe.

After his great victory in the 1965 Ulster Grand Prix, Franta had the traditional wreath placed around his neck by a pretty young Irish Colleen. Standing there baldheaded, by such a pretty young lass, one could not help but feel the impact of how long the old man has been racing his Jawas. Jawa and Stastny — a really great legend.