[TECHNICALITIES]

GORDON JENNINGS

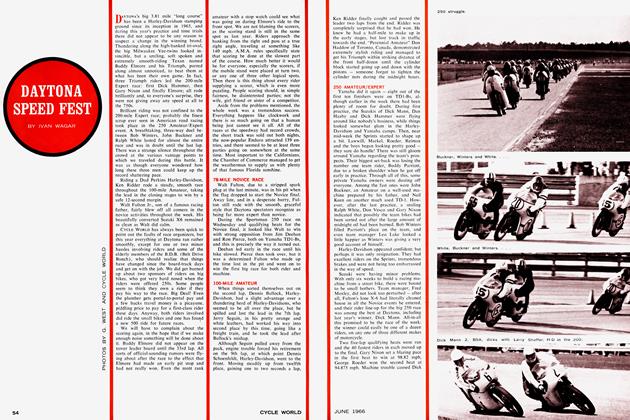

TECHNICALLY SPEAKING, the most significant overall factor at the 1966 Daytona road races was the unprecedented “factory” participation. Virtually all of the major names in motorcycling, with the notable and regrettable exception of Honda, had put together strong team efforts for this event. In fact, so impressive were the teams of such entrants as Yamaha International, that Harley-Davidson (once regarded as a racing juggernaught without peer) appeared a trifle low-key.

It was obvious that the Milwaukee Monolith’s racing mechanics were on hand primarily to aid the Harley-Davidson faithful. It was equally obvious around the Yamaha garage that theirs was a European-style team, with a strict separation of the duties of riders and technicians and little or no time for outsiders, Yamaha-mounted or not. On the basis of day to day observation, and on the end result, the latter method of doing business in racing (and a business it has become) would seem to be more effective. On the other hand, the Harley-Davidson system is a lot more helpful to private entrants. In the end, I suppose, it all comes down to a question of winning friends or winning races; it becomes increasingly difficult to do both.

With such very Big Brass as Edward Turner (Himself) and Harry Sturgeon from the BSA/Triumph organization in attendance, it was evident that American racing is being taken quite seriously by the Birmingham Small Arms Group these days.

There was very solid evidence of seriousness, too, in the equipment brought over for the BSA and Triumph Teams. These bikes were rather businesslike in appearance, and (compared to their road-going counterparts) were very special internally. An inside source told us a great deal about the BSAs, and it is interesting to know that while their engines were considerably modified, nothing that was done could be described as radical. In fact, it would be a simple matter for anyone racing a BSA twin to build a replica of BSA’s Daytona engine (with one exception).

Basically, these BSA engines have had just the normal “tuning” procedures applied, a light enlarging and smoothing of ports, bigger valves, racing carburetors, etc. As a matter of fact, if our information is correct, the camshaft used in these racing 500cc twins is one borrowed from the “hot” BSA A65 — right from the road-going Spitfire Mk II Special. The crankshafts were off-the-shelf items, but polished all over to eliminate “stressraisers” where cracks might develop. Polishing, and a slight amount of lightening was done with the valve-actuating rockers, and the pushrods received a similar treatment. More valve-train weight was saved with valve-spring retainers made of titanium, and by using valve stems of smaller-than-standard diameter. The final touch in the area of the valve gear was the fitting of American S&W racing valve springs. As I understand it, stock BSA high-compression (10.5:1) pistons were used, and the individual tuner in this country would probably obtain a set of pistons from some outside supplier to push the compression ratio a bit higher. That would yield slightly more power, but I think that the 10.5:1 pistons are a good thing for a 200-mile race.

Another good thing for a long race, or for a season of short races, is BSA’s use of pressure-feed lubrication throughout these racing engines. Oil holes have even been provided in the cam lobes, and of course there are drillings to feed a considerable flow of oil to the crankpins, as the rods have “plain” bearings.

An interesting point on the racing engines, and one that the private tuner may have some difficulty in duplicating, is the replacement of the timing-side mainshaft bushing with a ball bearing. On the drive side of the crank, a roller bearing gives the necessary load capacity. Also, on the “factory” engines, it appears that the crankcases are sand castings, rather than the standard permanent-mold parts. Transposing from BSA practice in the case of the Victor, we see in this an indication that these racing crankcases are heavier, in section, than the stock equivalent.

We had heard rumors, some months ago, about these racing BSAs having special frames, and that proved to be the case. However, the racing frames follow almost exactly the pattern of the touring bikes. The difference is that the racing frame is fabricated from tubes having less wall-thickness, but made of a better alloy. Stock (in appearance, at least) forks were used, and a stock front brake. This front brake was, however, not equipped with stock linings. Ferodo “greenstuff” lining gave the brake the authority necessary for racing. The BSAs had disc brakes at the rear, which seems a bit backward to me, but then (due, no doubt, to some oversight) no one asked for my opinion.

I have it on good authority (from a couple of BSA’s riders) that the bikes had a very good range of power, and top speed near-enough the equal of anything at Daytona, but that they were a trifle flexible in the turns. Not bad, but slightly hinged-inthe-middle.

The Daytona Triumphs were birds similar in feather, with special frames to the stock layout and relatively uncomplicated engine modifications. But, I am told, the Triumph engines were fitted with special cylinder heads — these having a valve angle more shallow than standard. Presumably, their Amal GP carburetors would have a throat diameter of 1-3/16", like the BSAs. Also presumably, they would have lightened valve-gear and otherthan-stock camshafts, but these things are by no means certain. My contacts in the Triumph camp are not as numerous, or free-talking, as those at BSA.

(Continued on page 28)

Externally, the Triumphs showed more non-standard hardware than the BSAs. They had, for example, an oil cooler, which strikes me as being an excellent idea. Oil gets extremely warm during a long race, and when hot it neither lubricates nor cools the engine’s bearings as well as it should. Gathered up in a big lump, in an oil tank, it is in no position to lose much heat. There is no very great increase in complication or weight in inserting a small aluminum radiator in the return-line to the oil tank, and this should do wonders for reliability.

One feature of the Daytona Triumph that was a bit puzzling was the placement of the exhaust pipes: both pipes and megaphones high, and on the left side of the motorcycle. I suspect that this was done because the Triumph Tiger T100C, which the Daytona Triumph was supposed to be an elaboration upon, has a similar exhaustpipe setup — though without the megaphones, of course.

Doug Hele, late of Norton’s Racing Department, was responsible for these Triumphs, and that may help to explain why these bikes were, in fact, faster than the BSAs from the same parent company. Mr. Hele’s experience with Norton has obviously taught him a lot about roadracing preparation — particularly with regard to handling. It was in this area that the Triumphs appeared to have the most pronounced edge, for with the possible exception of the Matchless G-50s, they were the best-handling big-displacement motorcycles at Daytona. That is, I suppose, only natural. The late-model Triumphs, with their new forks and revised steering geometry, must be rated among the besthandling mass-produced motorcycles available today.

We hear rumors that these road-racing BSAs and Triumphs are to be built in limited quantities and sold to privateers in America and elsewhere. This would not be too surprising, as both companies have made available such “production-racers” in the past. I certainly hope that the rumors are correct. The availability of ready-to-race equipment like this would have enormous benefits for the sport, and I am quite sure it would be a paying proposition for the companies concerned; paying, if only from the standpoint that their American racing program would be enormously strengthened. At present, preparation is left to the dealers and private owners, and it is all too evident that some of them do not fully understand about road racing just yet.

A big surprise for everyone at Daytona was the speed shown by the Suzukis. These motorcycles were gussied-up X-6s, built in a great tearing rush at the last minute, and for a time it appeared that they might actually do everyone in the eye. The Suzukis had been equipped with 27mm Japanese Amal carburetors, exactly like those on the TD-1B Yamahas, a home-grown magneto, and had exhaust and intake duration extended slightly; all of these modifications being developed by the people at Suzuki’s American distributing organization. Suzuki, in Japan, contributed the expansion chambers; nothing more.

Apart from the changes just mentioned, the Daytona Suzukis were very stock, even down to their brakes. Ultimately, the factory will be sending along true productionracing bikes, and these, when available, should enliven the action in the 250 class more than somewhat. Considering that the “overnight” version was so fast, the “realthing,” with better brakes and handling, should really be a tiger.

Having had an opportunity to race against the Suzukis, I can tell you from first-hand experience that they are fast. At present, their handling and braking is not entirely up to racing standards, but these are things fairly easy to correct when there is time for the sorting-out process.

Suzuki’s problem at Daytona was a rapid closing of magneto point-gap due to wearing of the point blocks. The breaker cams had been ground with a profile creating an excessive loading of the point blocks, and there was not time to correct this after the problem had been located. Various lubricants were tried, to no avail, and Walt Fulton Jr.’s bike had small bits of brass rod implanted in its point blocks to slow the rate of wear. Surprisingly, this lash-up worked well enough to allow Fulton to win in the Novice race. A more scientific “fix” applied to the Expert-class machines did not work, and all the Suzukis lost their spark very early in the Expert/ Amateur 100-miler.

At this point I will mention my new toy: a Harley-Davidson CRTT Sprint road racer. Having done a season on a Yamaha TD-1B, I felt that it might be fun to run a 4-stroker for a while. Certainly, riding the Yamaha provided me with an accelerated course in “Two-Strokes and What Makes Them Run.” Although I have only done two races on the Sprint (a local event and Daytona) the educational process is already shaping-up fast.

The first lesson learned was that the box-stock Sprint CRTT is not as fast as a first-rate, properly-tuned Yamaha TD-1B. Very nearly, but not quite. The difference is little enough to allow the Sprint rider to draft the Yamahas, and that is what all us lads on Sprints were doing at Daytona. Hanging-draft, and waiting for a chance to use the Sprint’s slightly better handling and brakes.

While engaged in this exercise around Daytona’s oval, some interesting things came to light. One was that while the Sprint would slow a bit when fighting one of the head-winds that arose from time to time, engine speed would only drop to about 9,200 rpm (in 5th) unless a veritable hurricane was blowing. The Yamahas, on the other hand, seemed to slow quite badly when bucking a wind, indicating a very peaky power curve.

A power-curve problem with the Sprint was present, too. I would be almost willing to wager that the Sprint’s power curve is a trifle concave between 9,200 and 9,800 rpm. Or, that the power curve and total drag (aerodynamic and rolling resistance) curve were parallel and nearly overlapping in 5th gear. Acceleration in that speed range was agonizingly slow, and if there was any head-wind, the tachometer stayed at 9,200. If, on the other hand, I could use someone’s slip-stream to climb up to 9,800, the Sprint would then pull itself right on up to just over 10,000 rpm. On several occasions, I was able to pick up a tow from a bike going past while the Sprint had stuck at 9,200 rpm, use the other bike to get to 9,800 and then pull out and repass with the Sprint singing merrily at 10,000 rpm. A curious phenomenon.

With all of the factory/distributor-supported teams contesting the 250cc class, it was pleasing to observe that many of the various production-racers in the hands of private tuners were going extremely well. Sprints, right from the box and privately entered, were equalling the speed of those under the direct supervision of the HarleyDavidson racing department. And many of the Yamahas outside the Yamaha International Team were as fast, or faster, than those looked after by Japanese technicians. What all of this means, is that the privateer can compete with the factorysupported teams. John Buckner, riding one of the world’s oldest TD-1 Yamahas (an

“A” chassis with an old “B” engine) came within a sneeze of winning the Expert/ Amateur 100-miler, and the other half of his racing team is his father. Leo Buckner, definitely not a Japanese technician — is, in fact, not even directly connected with the motorcycle business — but he has learned how to get the most from a Yamaha, and how to keep it together. No bigdeal secrets; just careful port-matching and equally careful assembly procedures. So, while you might have some problems trying to equal factory efforts in converting a touring motorcycle for racing, you can compete very effectively with one of these production-racers. Assuming, of course, that you put the required effort into basic preparation and that the required rider-talent is applied.

![[technicalities]](https://cycleworld.blob.core.windows.net/cycleworld19660601thumbnails/Spreads/0x600/14.jpg)