DUCATI HISTORY

GEOFFREY WOOD

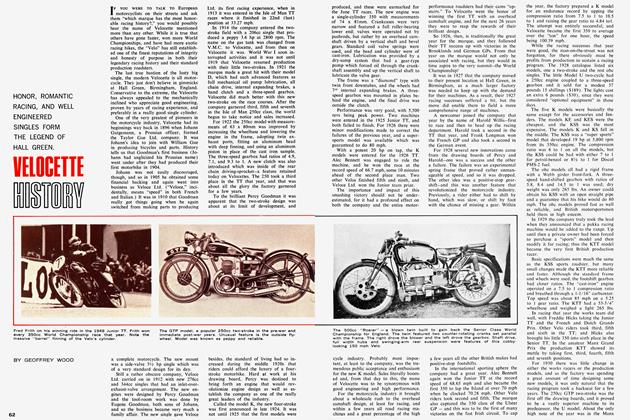

IN DISCUSSING many of the world's motorcycles we speak of their great days in the past when the marque produced scintillating mounts for the more sporting minded rider, or when they added illustrious chapters to the colorful saga of motor racing. When we speak of Ducati, we speak of the present, because the Ducati is truly one of the most modern of all the motorcycles being produced today.

The story of this Italian masterpiece begins only a few years ago in 1950 when the Bologna factory was rebuilt after the devastation of the war. Previously, the company had never produced motorcycles, but it was decided they would enter the motorbike field because post-war Italy needed personal transportation at a price that the rather poor populace could afford.

With the capital stock partly owned by the Italian government and the Vatican, the company had the financial resources to launch a line of 48cc and 65cc motorbikes and a 175cc scooter. These models proved to be well-designed, peppy little mounts, and the company was on its way to success.

As post-war Italy flexed its economic muscles, the standard of living slowly increased, and, quite naturally, the Ducati concern grew right along with it. In 1954, the factory hired Ing. Fabio Taglioni to head up the design work, and this move proved to be an excellent one as Taglioni’s genius was soon manifest.

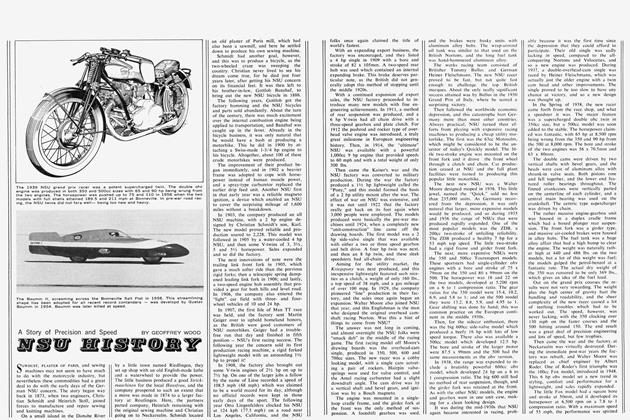

By 1955, the Ducati was rapidly becoming a best seller in Italy, and the inexpensive little 65TS model was probably the star of the range. This 65cc four-stroke model produced 2.5 hp at 5,600 rpm for a maximum speed of about 44 mph. The suspension system was very advanced for those days, with a swinging-arm on the rear and an orthodox telescopic fork on the front. A comfortable dual seat was fitted, and, to satisfy the Italian desire to be a “racer,” a small racing type windscreen was mounted over the handlebar. This windscreen bit seems very strange on a 44 mph motorbike to anyone except an Italian, but it made the 65TS a “sports” mount and this must have been important to the Latins, because the motorcycle sold in great numbers.

In 1956, the more affluent natives had their eyes on the 98S model, which offered more spirited performance than the 65cc Ducati, This new 98cc ohv motorbike had a more potent powerplant, producing something like 6.5 hp at 7,000 rpm for a maximum speed of 56 mph. The 98S model looked considerably more rugged than the smaller edition, and it had a heavier “open” type frame along with larger brakes to match the performance. The front tire was a 2.50 x 17 inch and the rear was a 2.75 x 17.

Still catering to the Latin desire for a “racer,” the 98S had a small handlebar fairing complete with a tiny racing windscreen. With low handlebars, the mount was supposed to look very fast, at least to the Italians, and this rather humorous accessory on a 56-mph motorbike helped sell the 98S model in goodly numbers.

Ing. Taglioni had not been hired just to design roadsters. His great passion in life was in fire-breathing racing engines. Hard at work on his brainchild, Taglioni was destined to produce a truly great racing engine — and on a meager budget at that.

It was not until the 1956 Swedish Grand Prix that the new racer appeared, but the impact of the design was tremendous, as it set the whole motorcycle racing world to talking. The engine displaced 125cc and featured a desmodromic cylinder head that allowed fantastically high revs with no fear of valve float. Desmodromics, for those of you who are unfamiliar with the term, means positive valve control, and in the Ducati this meant simply that there were a pair of cams to push open the valves and another pair of cams to pull them shut. Valve springs, therefore, were dispensed with, and this positive mechanical process meant that valve float was eliminated right along with the dangers of “holing” a piston or failing the valve gear through overstressing the components. At any rate, Degli Antoni astounded the racing world by riding the “desmo” machine to victory over its more established rivals in its first race. Then, just to seal the company’s reputation, the Ducati team of Fargas-Ralachs rode a 125cc model into first place in its class in the Barcelona 24-hour Grand Prix d’Endurance — a true test of stamina and reliability at speed.

The early success of the marque declined a bit during 1957, when the company concentrated its resources on the introduction of the new 175cc ohc “T” and “S” (touring and sport) models, and these were followed in 1958 by the 100 and 125cc “Sport” models. By then, Ducati’s goal was obvious; they were out to expand their sales to all comers of the world. To do this meant two things: they would have to produce a line of really good motorcycles, and then they would have to get the message across to riders all over the world. The new ohc Ducatis certainly fulfilled the first requirement, and for the second it was decided, and wisely so, to conduct an aggressive campaign on the world’s grand prix tracks. This racing effort would have to be conducted on a slim budget, though, because the company was still rather small and the funds were not too plentiful.

As far as world-wide sales were concerned. Ducati had a really fine machine in the new 175cc ohc model. The 175cc alloy engine, with a 62mm bore and a 58.8mm stroke, produced 11 hp at 7,500 rpm for a maximum speed of 68 mph. Carburetion was handled by a 22mm Dellorto, and the valves were inclined at 80 degrees to each other. The compression ratio was a modest 7:1.

The engine’s lower end featured a rugged ball and roller bearing assembly, and the crank and transmission cases were cast in one clean-looking unit. The gearbox had four speeds. This engine-gearbox case was mounted in an exceptionally well designed frame which used a swinging-arm rear suspension and a telescopic front fork of outstanding quality. The brakes were very large and were housed in beautifully finished alloy hubs. The whole bike had an exceptional finish, and the engine had Allen-type screws instead of the slotted screws on the covers.

These 175cc models were followed by the 100 and 125cc sports models in 1958, which were produced more for domestic consumption. The little 100 Sport model proved very popular with the Italians because it provided a speedy little tourer to very sporty specifications at a cost factor that they could afford. Similar to the 175cc models except in size, the engine had a 49mm bore and a 52mm stroke. A compression ratio of 9 to 1 was used along with an 18mm carburetor, and the little lunger pumped out 8 hp at 8,500 rpm. Top speed was listed as 65 mph.

During 1957, the factory spent their time in developing the 125cc desmodromic engine and improving their standard production range. Their racing successes, quite naturally, declined a bit. Just to keep their name alive and to prove that 1956 was no fluke, the factory sent Bruno Spaggiari and Alberto Gandossi to Spain for the 24hour Barcelona event. Once again the I25cc ohc proved to be reliable as the team garnered first place at record speed in the 125cc class.

In the winter of 1957-58, the factory shops were very busy. The Ducati management had aggressively set up an extensive dealer network all over the world, and retailers in the European countries, North and South America, the Orient, and Australia, all had this new line of ohc singles to sell. The management promised these new dealers all over the world that, by the end of the year, Ducati would be renowned as a great motorcycle.

To get the Ducati recognized meant just one thing — successful participation in world championship racing. To this end the factory dedicated itself in the spring of 1958. It would take some determined work to show the world the brilliance of Ing. Taglioni’s designs. Still a relatively small company, Ducati did not have the finances to hire the very top riders or conduct a massive racing campaign. Still, they had the desmodromic engine, and, by choosing their battlegrounds, they just might steal the whole show.

The very summit of international racing is the Isle of Man TT, and the marque decided to start the season there. Handicapped by not having riders with a great deal of experience on the island course, the Ducati team didn't really expect to defeat Carlo Ubbiali and his MV Agusta. The team did put up a courageous battle, however, and Romolo Ferri, Dave Chadwick, and Sammy Miller took second, third, and fourth places.

The next battleground was the Dutch Grand Prix at Assen, and when the little 125s were pushed off the grid, it was Alberto Gandossi and Luigi Taveri who led the first lap. After a fantastic battle it was Ubbiali again, though, with Taveri, Gandossi. and Chadwick taking second, fourth, and fifth places. Taveri was beaten by just a few yards, though, and he did have the honor of making a record lap.

Then followed the Belgian GP at Spa. and this was w'here the tide turned. The previous races had been on the slower, more twisty courses where Ubbiali's brilliant riding gave him an advantage, but now the season was to enter the faster courses where horsepower would show. The result was a smashing victory for Ducati, with Gandossi, Ferri. Chadwick, and Taveri taking first, second, fourth and sixth places.

The next race was the German event at the Nurembergring and once again the Ducatis streaked into the lead. Displaying superior speed over the world champions, the Ducati riders steadily pulled away. Then, disaster struck. Ferri crashed, Tavcri's engine went off song, and Gandossi's model broke down.

Then followed the Swedish Grand Prix at Hedamora, and Gandossi and Taveri once again were the victors, with Ubbiali taking a had drubbing into third place. Next wa~ the fast t]lster event, only that \car the race was run in a driving rain. (andossi rode like a tiger that da~ and, with two laps to go. he held Ubbiali at clocking 107.9 mph on the Lea themsto~~ n Straight. Then. on the hairpin. Gandossi lost the model on the slippery road. He was able to remount and finish fourth, with Taveri and Chadwick in second and third: but with his crash went his last chance for the world championship. The final event of the 1958 season was at home on the fast Monza circuit. With great prestige at stake here, the two antagonists made great preparation for the race. This final chapter in a season of torrid racing was destined to he Dticatis. though. as the marque quite literali~ slaughtered the mighty \lVs by taking the first five places. The final order was I3runo Spag~iari. (iandossi. Fr nccsco Vii Ia. Chadwick. and Taveri. All Ihe Ducatis were desmo singles except Villa's mount, which had a new twin cylinder engine.

So the curtain fell on a courageous effort by a small factory — and it very nearly proved successful, too. as only Gandossi's spill in the waning laps of the Ulster Grand Prix stood between him and the championship. This racing campaign was eminently successful for what it was intended to do, however, and that goal was to put Dueati "on the map” all over the world. Almost overnight the marque became famous and sales sharply increased. The year of 1958. then, must be regarded as the turning point for Dueati. And just to add some frosting to the cake, the team of Mandolini-Maranghi once again took the 125cc class at the 24-hour Barcelona event to cap a really great year.

For 1959. Dueati planned a racing campaign that would keep them in the news, but it was neither as extensive nor expensive as the all-out effort of the previous year. Some remarkably good results were obtained, however, with outright victories by Ken Kavenagh in the 125cc Finnish Grand Prix and by Mike Hailwood in the Ulster event. Hailwood also garnered a third at the Isle of Man, and other Dueati riders took fourth, fifth, and sixth in the Ulster, as well as a third in the Monza classic. Then, once again, the Dueati team of Flores-Carrero won the 125ec class at the 24-hour Barcelona grind on a standard production 125cc Sport model.

In 1959, the standard production range was increased with the 85cc Bronco, which was derived from the older 98cc model, and this was later enlarged to a I25cc powerplant. During 1960, the ohc I75cc models were enlarged to 200cc, and in 1961 and 1962. the Piuma Sport and Falcon 48cc two-strokes were added to the range of motorcycles.

During I960, Dueati racing successes took a sharp turn downward as the factory changed its competition policy. Racing in world championship classics had achieved what the company wanted in the way of publicity and sales, and so the factory turned its efforts toward improving production models and building racing bikes for the private owner. These production racers have achieved a great number of victories and placings in Furope. Argentina. Canada, the United States. Africa. Venezuela, Brazil, Uruguay, Ecuador, Chile, Australia, and the Orient, and in all these places the Dueati name has become synonymous with performance.

This knowledge gained in racing has been incorporated into the standard production models, and the 200cc ohc engine was enlarged to 250cc in 1962 and produced as a super sports model (Diana), a tourer (Monza), and a scrambler. In 1963, the factory began production of the lOOcc Cadet and Mountaineer models, and then the 48cc and lOOcc scooters. Lastly, in 1965. the 250 acquired a five-speed gearbox and new 160cc and 350cc ohc models made their debut.

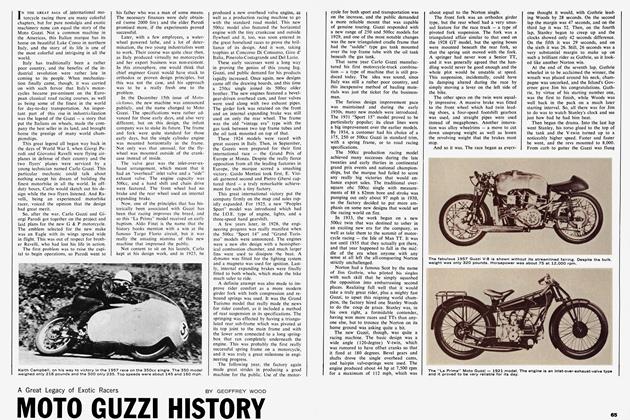

The Diana MK III is probably the star of the current range, and this 250cc sportster is for the enthusiast who likes to play road racer on weekends. American road tests have obtained speeds of around 104 mph on this bike, which is truly remarkable performance. The fine handling and powerful brakes are also exceptionally good, and the Diana is probably about as close as a fellow can come to running a pukka road racer on the street. The fittings on the Diana are all rather sporting with low bars, an extra megaphone exhaust. tachometer, and rear-mounted footpegs and brake-gearshift levers as standard equipment for the machine.

For more sedate touring, the Monza model is the answer, with a lower performance engine and more comfortable accessories. For motocross fans there is the 250cc scrambles model. The 350cc Sebring and 160cc Monza Junior models complete the range.

In Furope, the Ducati line is slightly different than in the U.S.. with the Mach I replacing the Diana model. This Mach T is claimed by Ducati to be the fastest standard production 250cc motorbike in the world, and few there are that argue with this claim. Several British road tests have attained 106 mph with the muffler intact — which is about tw'o mph faster than stateside tests of the Diana with a megaphone. Chief differences between the Mach I and Diana are battery ignition, low bars, fuel tank, seat, tachometer drive, larger valves, and a different camshaft.

For pukka racing there are 250cc and 350cc racers available which offer excellent performance on the track. The Ducati racer features a massive double, twinleading-shoe front brake and a full duplex cradle frame. The low'er half of the engine is similar to the works racers, but the top half has the conventional single overhead camshaft. Powder output is rated as 34 hp at 8.500 rpm on the 250cc engine and 39.5 hp at 8,000 rpm on the 350cc version. Both engines have twin spark ignition and five-speed gearboxes.

Ducati's aim in producing these racers for European sportsmen is to supply a racing bike that handles w'ell, performs reasonably well, is reliable, and yet sells at a cost low enough so that almost anyone can afford it. A more powerful engine could, no doubt, be supplied, but the cost would soar and reliability would decline as a result.

Since the change in racing policy from exotic works desmodromic engines to production racers and clubman-type racing, Ducati has continued to establish an enviable reputation. In the classic 24-hour Barcelona race for production or prototype models, the team of Villa and Balboni took a 175cc model into a remarkable first place ahead of the works 600cc BMW in 1960. The next success was in 1962 when the Fargas-Rippa team took another first, this time in the 250cc class.

Then, in 1964, came perhaps the marque’s greatest hour when the team of Bruno Spaggiari and Giuseppe Mandolini took a 285cc single ohc model into an outright win going the record distance of 2415 kilometers — the first time that 100 kph had been achieved for the 24 grueling hours. All this was done, mind you, against the finest big-engine teams that Europe could produce. Still displaying their stamina, stemming from good engineering, the Ducati team of Cere-Giovanardi again took a first place overall in the 1966 Imola Six-Hour Race, one of the big races counting for the Coup d’ Endurance award. Behind the winning Ducati 250 were many big motors up to 750cc.

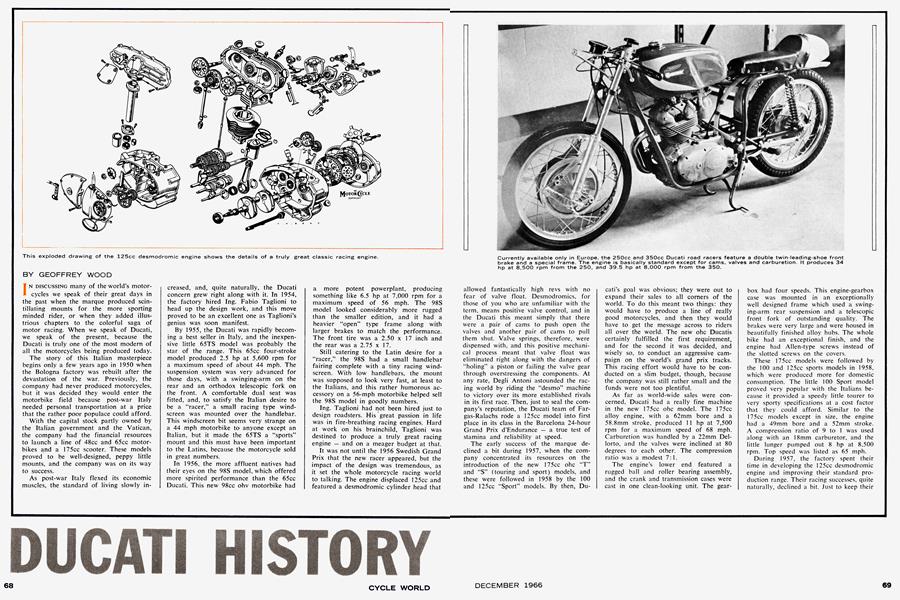

And so ends the story of the growth of Ducati. But, before we leave this speedy little Italian, let's go back to that fabulous tiny desmodromic engine and take a peek under the gas tank. A truly great classic in the annals of European motorsport, the 125cc Ducati is the only successful desmodromic motorcycle engine to have ever been raced. Produced by a brilliant engineer, the project was handicapped by a slim racing budget and a shortage of really top-flight riders. Nevertheless, it achieved some dramatic victories and added a chapter to motorsport history.

Taglioni first sketched out his desmodromic layout in 1948, but it was not until 1954, when he was hired by Ducati, that he could get down to the actual design w'ork. In 1955, the first engine was assembled, and in 1956 it was entered in its first race in Sweden.

The little 125cc desmo engine had a bore and stroke of 55.25 x 52mm, and was the same as the marque's single and double overhead cam engines from the cylinder top downward. The two cams that opened the valves were located on spur gears in much the same manner as a double overhead camshaft engine. On the middle shaft was located the closing cams which had, of course, an inverted profile, and these closed the valves via short rocker arms. These rocker arms were attached to the valve stems through flanged collars located by split wire rings sprung into grooves in the stem. The valves were closed to within 0.012 inch of their seats, and the internal compression pressure then closed them onto the seats.

The valves themselves were inclined at an 80-degree angle, and the inlet and exhaust lifts were 8.1mm and 7.4mm, compared to 7.5mm and 7mm on the standard twin-cam Grand Prix model. The throat diameter of the valves was 31mm on the inlet and 27mm for the exhaust. Carburetor bore size was 22 or 23mm for use on tight, twisty courses which put a premium on acceleration, 27mm for typical grand prix courses, and 29mm for very fast circuits such as Monza or Spa-Francorchamps. The compression ratio was 10 to 1.

(Continued on page 93)

Cont.

Power output was 19 hp at 12,500 rpm. compared to 16 hp at 12,000 rpm on the twin-cam Grand Prix model. The little desmo twin that Francesco Villa used in the 1958 Monza classic had a bore and stroke of 42.5 x 45mm and pumped out 22.5 hp at 14,000 rpm: but at the time the single was more raceworthy because of its wider torque range. The maximum speeds with dolphin fairings were 1 12 mph for the single and 118 mph for the twin.

The frames that these splendid little engines were mounted in were quite orthodox for their day and the handling was never reputed to be anything exceptional. Fiveor six-speed gearboxes were used, depending upon the circuit, and twin-coil ignition was employed. The oil sump was contained in the crankcase and the oil lubricated both the engine and transmission. A castor-base oil of SAF 20 weight was used, and fuel consumption averaged about 45 mpg.

Another interesting Ducati produced in 1959 was a 250cc desmodromic twin that turned to 11,800 rpm. The factory produced just this one model, built especially for Mike Hailwood, and then lost interest in racing. On this fabulous twin, Hailwood set his homeland short circuit races alight as the screaming Ducati smashed many a race and lap record.

Today, the racing efforts of the marque are concentrated toward the European production machine racing where they do so well, and the improvement of their rather secretive experimental models. The regulations for the Coup d’ Endurance racing trophy allow some modifications from standard production practice for experimentation, and Ducati has taken advantage of this. The result has often been some surprising victories against much larger engines, and the company has benefited immensely from the publicity.

All this participation in racing their production models has had its benefits to Ducati, and the knowledge gained is usually incorporated into the standard production range. With a constant technical improvement to their basic ohc design, the present-day Ducati range must he considered one of the most modern in the world.

From scooters and inexpensive lightweights on up to the fabulous 250 Diana MK III. here is a motorbike that appeals to the knowledgeable enthusiast. Quality of workmanship and race-bred design go hand in hand at Bologna. ■