VELOCETTE HISTORY

HONOR, ROMANTIC RACING, AND WELL ENGINEERED SINGLES FORM THE LEGEND OF HALL GREEN.

GEOFFREY WOOD

IF YOU WERE TO TALK TO European motorcyclists on their streets and ask them "which marque has the most honor able racing history?," you would possibly hear the name of Velocette mentioned more than any other. While it is true that others have gone faster, won more World Championships, and have had more exotic racing bikes, the "Veto" has still established one of the finest reputations of integrity and honesty of purpose in both their legendary racing history and their standard production roadsters.

The last true bastion of the lusty big single, the modern Velocette is all motor cycle. They just don't believe in gimmicks at Hall Green, Birmingham, England. Conservative to the extreme, the Velocette has always appealed to the mechanically inclined who appreciate good engineering, proven by years of racing experience, and preferably in a really good single cylinder. One of the very greatest of pioneers in the motorcycle industry, Velocette had its beginnings way back in 1896 when Johann Gutgemann, a Prussian officer, formed the Taylor Gue Ltd. company. It was Johann's idea to join with William Gue in producing bicycles and parts. History tells us that Goodman's first business (Jo hann had anglicized his Prussian name) went under after they had produced their first motorbike in 1904.

Johann was not easily discouraged, though, and so in 1905 he obtained some financial backing and again went into business as Veloce Ltd. ("Veloce," inci dentally, means "speed" in both French and Italian.) It was in 1910 that Goodman really got things going when he again switched from making parts to producing a complete motorcycle. The new mount was a side-valve 3½ hp single which was of a very standard design for its day. Still a rather obscure company, Veloce Ltd. carried on in 1912 with new 276cc and 344cc singles that had an inlet-over exhaust-valve arrangement. The new engines were designed by Percy Goodman and the tool-room work was done by Eugene Goodman, both sons of Johann, and so the business became very much a family affair. The new single gave Veloce Ltd. its first racing experience, when in 1913 it was entered in the Isle of Man TT races where it finished in 22nd (last) position at 33.27 mph.

In 1914 the company entered the two-stroke field with a 206cc single that produced a peppy 3.6 hp at 2800 rpm. The name on the gas tank was changed from V.M.C. to Velocette, and from then on Velocette it was. World War I soon interrupted activities and it was not until 1919 that Velocette resumed production with their little two-strokes. In 1921 the marque made a great hit with their model D, which had such advanced features as full mechanical oil pump lubrication, all chain drive, internal expanding brakes, a hand clutch and a three-speed gearbox. Velocette did much better with this new two-stroke on the race courses. After the company garnered third, fifth and seventh in the Isle of Man 250cc class, the world began to take notice and sales increased. For 1922 the 250cc model with measurements of 63 x 80mm was improved by increasing the wheelbase and lowering the engine in the frame, adopting twin exhaust ports, fitting an aluminum head with deep finning, and using an aluminum piston in place of the cast iron sample. The three-speed gearbox had ratios of 4.9, 7.1, and 9.3 to 1. A new clutch was also introduced which was inside of the rear chain driving-sprocket-a feature retained today on Velocettes. The 250 took a third place in the TT that year, and that was about all the glory the factory garnered for a few years.

To the brilliant Percy Goodman it was apparent that the two-stroke design was about at its limit of development, and besides, the standard of living had so in creased during the middle 1920s that riders could afford the luxury of a four stroke motorbike. Hard at work at his drawing board, Percy was destined to bring forth an engine that would revolutionize engine design as well as es tablish the company as one of the really great leaders of the industry.

Called the model K, the new four-stroke was first announced in late 1924. It was not until 1925 that the first models were produced, and these were earmarked for the June TT races. The new engine was a single-cylinder 350 with measurements of 74 x 81mm. Crankcases were very narrow and featured a full roller-bearing lower end; valves were operated not by pushrods, but rather by an overhead camshaft driven by a vertical shaft and bevel gears. Standard coil valve springs were used, and the head and cylinder were of cast-iron. Lubrication was provided by a dry-sump system that had a gear-type pump which forced oil through the crankshaft assembly and up the vertical shaft to lubricate the valve gear.

The frame was a "diamond" type with twin front downtubes, and the wheels had 1" internal expanding brakes. A three-speed gearbox was mounted in plates behind the engine, and the final drive was outside the clutch.

Performance was very good, with 5,500 revs being peak power. Two machines were entered in the 1925 Junior TT, and both failed to finish. For 1926 there were minor modifications made to correct the failures of the previous year, and a supersports model was available which was guaranteed to do 80 mph.

With a potent 20 hp on tap, the K models were entered for the 1926 TT. Alec Bennett was engaged to ride the machine, and he won the race at the record speed of 66.7 mph, some 10 minutes ahead of the second place man. Two other Velos finished fifth and ninth, and Veloce Ltd. won the Junior team prize.

The importance and impact of this smashing victory should not be underestimated, for it had a profound effect on both the company and the entire motorcycle industry. Probably most important, at least to the company, was the tremendous public acceptance and enthusiasm for the new K model. Sales literally boomed and, from that day to this, the name of Velocette was to be synonymous with good engineering and high performance. For 1930 there was little change in either the works racers or the production models, and as the factory was spending a great amount of time designing some new models, it was only natural that the racing program took a backseat for a few years. The 250cc GTP two-stroke was the first off the drawing boards, and it proved to be a vastly superior machine to its predecessor, the U model. About the only high note of the year was in the Manx Grand Prix where 350cc KTTs garnered the first eight places in the Junior Class, as well as a surprising second place in the Senior.

For the motorcycle industry it brought about a wholesale rush to the overhead camshaft design, at least for racing, and within a few years all road racing machines and a great percentage of the high performance roadsters had their cams "upstairs." To Velocette went the honor of winning the first TT with an overhead camshaft engine, and for the next 26 years they were to reap the rewards of their brilliant design.

So 1926, then, is traditionally the great year for the marque, and they followed their TT success up with victories in the Brooklands and German GPs. From that year on the marque would not only be associated with racing, but they would in time aspire to the very summit—the World Championship!

It was in 1927 that the company moved to their present location at Hall Green, in Birmingham, as a much larger factory was needed to keep up with the demand for their machines. As a result, their 1927 racing successes suffered a bit, but the move did enable them to field a more comprehensive range of machines.

A newcomer joined the company that year by the name of Harold Willis first to race and then to head up the racing department. Harold took a second in the TT that year, and Frank Longman won the French GP and also took a second in the German event.

For 1928 several new innovations came from the drawing boards of Percy and Harold one was a success and the other a failure. The failure was an experimental spring frame that proved rather unmanageable at speed, and so it was dropped. The other idea was a positive-stop gearshift was another feature that revolutionized the motorcycle industry. Previously, a rider either had to shift by hand, which was slow, or shift by foot with the chance of missing a gear. Within a few years all the other British makes had positive-stop footshifts.

In the international sporting sphere the company had a great year. Alec Bennett again won the Junior TT at the record speed of 68.65 mph and also became the first 350 to lap the Island at over 70 mph when he clocked 70.28 mph. Other Velo riders took second and fifth. The marque also captured the 350 class of the Ulster GP - and this was to be the first of many victories on the fast Irish circuit. To cap the year, the factory prepared a K model for an endurance record by upping the compression ratio from 7.5 to 1 to 10.5 to 1 and raising the gear ratio to 4.84 tol. The attempt was entirely successful, and Velocette became the first 350 to average over the "ton" for one hour, the speed being 100.39 mph.

While the racing successes that year were good, the man-on-the-street was not forgotten, for there obviously must be profits from production to sustain a racing program. The 1928 catalogue listed six models, one a two-stroke and the rest ohc singles. The little Model U two-cycle had a 250cc engine coupled to a three-speed gearbox and it sold for a modest 37 pounds 15 shillings ($189). The lights cost an extra 6 pounds ($30), since they were considered "optional equipment" in those days.

The five K models were basically the same except for the accessories and fenders. The models KE and KES were the cheapest, and the KSS was the most expensive. The models K and KS fell in the middle. The KSS was a "super sports" model that developed 19 hp at 5,800 rpm from its 350cc engine. The compression ratio was 6 to 1 on all the models, but the KSS could be had with either 7 to 1 for petrol-benzol or 8V2 to 1 for Discol PMS-2 fuel.

The ohc models all had a rigid frame with a Webb girder front-fork. A three-speed hand-shifted gearbox with ratios of 5.8, 8.4 and 14.5 to 1 was used; dry weight was only 265 lbs. An owner could obtain his KSS with an open straight pipe and a guarantee that his bike would do 80 mph. The ohc models proved fast as well as reliable, and British motor sportsmen held them in high esteem.

In 1929 the company truly took the lead when they announced that a pukka racing machine would be added to the range. Up until then a private owner had been forced to purchase a "sports" model and then modify it for racing; thus the KTT model became the very first British production racer.

Basic specifications were much the same as the KSS sports roadster, but many small changes made the KTT more reliable and faster. Although the standard frame and wheels were used, the footshift gearbox had closer ratios. The "cast-iron" engine operated on a 7.5 to 1 compression ratio and breathed through a 1-1/16" carburetor. Top speed was about 85 mph on a 5.25 to 1 gear ratio. The KTT had a 53-3/4" wheelbase and weighed a light 265 lbs.

In racing that year the works team did well, with Freddie Hicks taking the Junior TT and the French and Dutch Grands Prix. Other Velo riders took third, fifth and sixth in the TT; and Hicks also brought his little 350 into sixth place in the Senior TT. In the amateur Manx Grand Prix the production KTT showed its mettle by taking first, third, fourth, fifth and seventh positions.

During 1931 and 1932 the economic depression slowed things down a bit, and the company produced only one new model, a 350cc side-valver that stayed in production just one year. Some design improvements were also made to the racing machines in 1932, and the works bikes featured a new engine with hairpin valve springs and a downdraft intake port. The head was cast of aluminum-bronze and the engine turned over at 6,000 rpm. The frame was also modified to carry a IV2gallon fuel tank, and a new four-speed gearbox was used. These modifications were incorporated into the MK IV KTT, a very fine model capable of 95 mph on a fifty-fifty petrol-benzol fuel. The KTT continued to establish an enviable reputation, taking first in the 1931 Manx GP and second in 1932, plus many "places" in international classics.

In 1933 the company made another bold bid for sales with the introduction of the MOV model which had a 250cc pushrod-operated engine. The engine was square at 68 x 68mm and featured a narrow crankcase with an exceptionally rugged lower end assembly. The camshaft was located high in the timing case to keep the pushrods short and light, thus ensuring good valve control at high engine speeds. The MOV proved very popular as it was a reliable mount with a brisk performance. Subsequently, the 350cc model was produced in 1934 with measurements of 68 x 96mm, and this was followed in 1935 by the 500cc MSS with a bore and stroke of 81 x 96mm.

Meanwhile the racing department was not sitting still. The previous two years had not been very fruitful as the experimental work on a "long-stroke" 350 and a supercharged model had proved a failure. A new cambox was designed for both the works and KTT racers which enclosed the rockers but left the valves and springs exposed for cooling, and the twin downtube frame was replaced with a single-tube frame. The racing fortunes picked up a little with the KTTs taking fourth, fifth and sixth in the Junior TT; first, third, fourth and fifth in the Ulster GP, and firsts in the French, Brooklands and Manx GPs.

The marque moved forward in i 934 as sales began to climb when the world moved out of the depression, and at Hall Green some brilliant engineering work was being done in Harold Willis' racing department. A new cradle frame was adopted for the works racers which had a single front down-tube. The powerful IV2" x 7" brakes were housed in massive, conical hubs which were cast from magnesium alloy, and a new alloy cylinder with a cast-iron insert was adopted. Probably the most exciting was the announcement that a new 500cc works racer would join the 350cc mount.

The new 500 made a successful debut, finishing third in the Senior TT and then winning the Ulster Grand Prix at the record speed of 88.38 mph. Walter Rusk was the rider, and in the Ulster he became the first to lap the course at over 90 when he lapped at 92.13 mph. The 350 model also did well, taking fourth through tenth places in the TT, second and fourth in the Ulster, and first in the Swedish and French events.

The MK V KTT was introduced in 1935, and it had many improvements gained from works racing experience. The new cradle frame was used and the lubrication system supplied oil to the big end, top bevel gears and camshaft through a set of metered jets. The works racers were much the same as the year before. With the addition of Ted Mellors to the factory team, the marque's successes began the ascendancy. The Junior TT brought fourth, fifth and sixth; the Dutch GP had Velos in second and third; a second was obtained in the Spanish event; a win in the French; and then a first and second in the fast Ulster classic. The 500 did not see too much action, and a third in the Ulster was the only success.

It was apparent to the Goodman Brothers and Harold Willis that only an all-out campaign would dislodge the Nortons from their Junior and Senior class World Championships, and so for 1936 it was decided to make a great effort. Actually, the factory raced on a shoe-string budget and spent far less on racing than most of their competitors, but still they did succeed in hiring the great Stanley Woods for their works team.

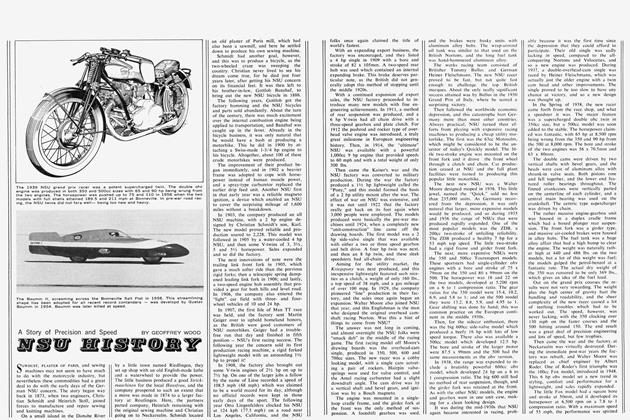

In the spring of 1936 the new works , racers rolled out of the race shop. The new frame was probably the most interesting as it had a swinging-arm rear suspension that proved to be another great Velocette contribution to motorcycle engineering. The rear shock units were an oil and compressed air type, the rider pumping them up to the desired pressure. The cradle had a Webb girder fork at the front, and massive conical hubs were retained with an air scoop on the front brake. Two new engines were used, the 350 having a double ohc head and the 500 having a single ohc engine. The 500 MSS was a beefy single with lots of torque, and it was very popular for sidecar work. The stars of the range were the KTS and KSS singles, the KSS being a sports version of the KTS. These ohc 350s were very popular with the sports-minded riders, and their quality of engineering and workmanship is legendary. The MSS, KTS, and KSS all used a heavier frame with a 55" wheelbase and they all weighed about 335 lbs. During 1936 and '37 a KTT model was not produced, but in 1938 the MK VII made its debut and it had all the latest refinements of the works racers except that the engine had its fins rounded off a bit and the frame was still rigid. Altogether a very fine range of quality motorcycles, and the models offered remained the same until the war.

The new Velos set a trend in riding comfort and handling as most everyone else was still using either rigid frames or plunger rear suspensions. Stanley showed his worth to the team that year with a second in the Senior TT, only 18 seconds behind Jimmy Guthrie's Norton, and the record lap at 86.98 mph. In the Junior TT Stanley retired with a broken bevel gear, but Ted Mellors brought the other 350 home third. The rest of the season proved more successful with Stanley winning the 500cc Spanish GP; and Mellors taking second in the Ulster behind teammate Ernie Thomas; a second in the Swedish; and wins in the French, Swiss and Belgian classics. This splendid record gave Ted the Junior Class World Championship — the very first for Hall Green!

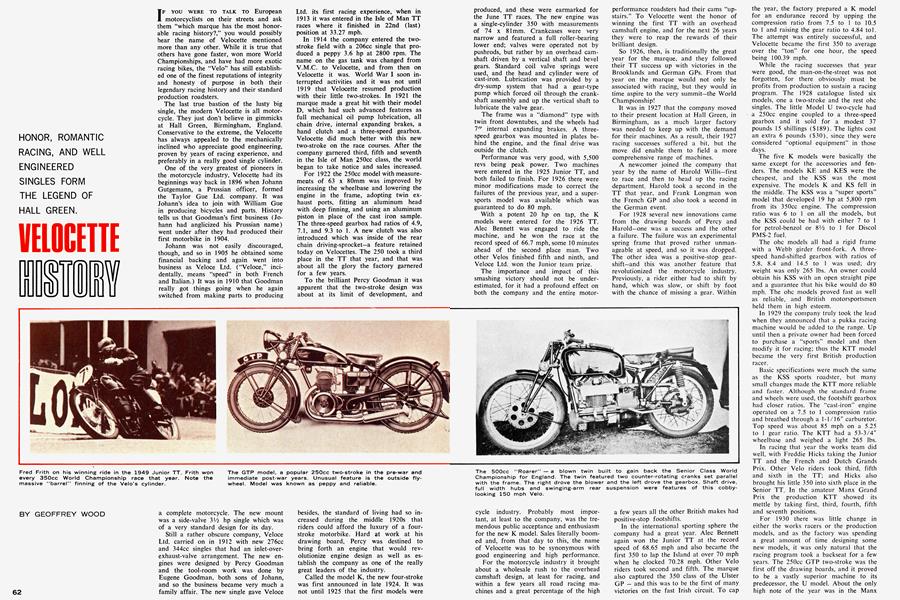

During the late 1930s the racing game became exceedingly competitive, so Harold Willis responded with new racers again for 1937. Both the Junior and Senior engines were single ohc as Harold came to distrust the reliability of the twin-cam unit. The new engines set a fashion in finning with a massive 9" square head that had the rockers, valves and springs totally enclosed; and a huge "barrel" cylinder. Tappet adjustment was by eccentric mounted rocker shafts, the alloy head had inserted valve seats (another Velo first), and the metered jet lubrication system pumped oil at the rate of one gallon every six minutes. The inlet port was downswept and the carburetor float was remote mounted on the oil tank. These were magnificent racing machines with the 350 capable of 117 mph on a 10.5 to 1 compression ratio and the 500 capable of 124 mph. Horsepower was listed as 32 at 7200 rpm on the 350 and 42 at 6,700 rpm on the 500.

So into the battle they went and again Woods took second in the Senior TT, beaten by only 15 seconds. In the Junior TT Stanley had problems and finished fourth. Ted Mellors had a great year on the 350, winning the Ulster, Swiss, Swedish, French and Italian classics, plus taking a second in the Belgian and a third in the Dutch. Velo and Mellors retained their Junior Class Championship!

Lest it be inferred here that all Velocettes did was race, let's return to the production models. The range had the GTP as a cheap utility two-stroke at the modest price of 41 pounds ($205). Next was the MOV 250 which weighed 275 lbs. and had a top speed of 65 mph. Then came the MAC 350, only 5 lbs. heavier than the MOV, and the MOV and MAC both used the frame with a 52!4" wheelbase.

The 1938 racing season saw a tremendous record, with Mellors and Woods gaining many victories: Mellors took second in the Junior TT and Belgian GP, and firsts in the Ulster, Dutch and Swiss classics. In addition, Woods won the Junior TT and set a record lap of 85.3 mph that was destined to stand for 12 years; and Stanley also took second in the Senior TT only 15 seconds behind Harold Daniell's Norton. Other Velo riders took second and third in the Senior Ulster behind Jock West's blowp BMW; third, fifth and sixth in the 350 Ulster; and second and third in the 350cc Dutch and Italian events.

It was apparent to the race shop that 1939 would be much tougher as the continental manufacturers were developing their blown racers to a tremendous level of performance. Realizing that supercharging was essential to trounce the blown BMW, NSU, Gilera and AJS, Willis and his crew built the "Roarer" during the winter. The design was most brilliant: a vertical twin with two counter-rotating cranks, the left one driving the gearbox and the right one driving the supercharger. Full width hubs and a massive fuel tank made the Roarer one of the most potent-looking racers ever, but World War II halted all development work. The twin was given an airing in TT practice, but Harold Willis passed away just a few days before the race and it was decided to use the faithful old single. By late summer the dyno tests gave readings that would provide about 150 mph, and at 370 lbs. the twin was much lighter than some of the other supercharged speedsters of the day.

During the 1939 season the 500 singles along with their arch-rivals — the Nortons, were simply overwhelmed by the supercharged Gilera and BMW teams. Stanley came fourth in the Senior TT and Les Archer captured third in the Ulster, and that was about it in the Senior Class. Ted Mellors and his 350 model fared better, but every race was a tremendous battle against the blown DKW two-strokes. Ted started with a fourth in the Junior TT; then took seconds in the Dutch, French and Swedish events; and then he won the Belgian to narrowly retain the Championship from the DKW. Other 350 Velo riders took second in the Belgian (Woods), second and third in the German GP, and Stanley once again won the Junior TT.

Before leaving 1939 we must mention the MK VIII KTT which featured the swinging-arm suspension (another Velo first on production racers). With a 10.9 to 1 compression ratio, the 350 was capable of about 12 mph at 7,200 rpm on a 5.0 to 1 gear ratio. These MK VIIIs were splendid racing machines, noted for their fine handling and stamina, and they garnered 25 of the first 35 positions in the 1939 Junior TT ; finishing a tremendous 77% of their starters.

Then, during the War, the factory was switched over to military production. After the war the models produced were much the same as in the pre-war days, except that in 1947 the GTP model was dropped. In line with the industry-wide post-war trend to telescopic forks, the Velos all appeared in 1948 with a new air-oil fork that contained no springs. Then, in 1949, the KSS, MOV and MSS models were dropped and the model LE made its debut. The 150cc LE was an "everyman's" motorcycle with a side-valve water-cooled flat twin engine, shaft drive, and semi-enclosed for ultraclean running.

The marque's racing successes were much the same as before the war — top dog in the 350 class and antagonist in the 500 class. Bob Foster won the 1947 Junior TT with other Velo riders in second, third and fourth places. Peter Goodman came third in the Senior after a slow start, and Peter also turned the fastest lap of the race. On the continent the 350cc Dutch and Swiss GPs fell to Velo along with a second in the Ulster classic.

In 1948 Fred Frith led the team (he had joined Velo in 1947 but broke his collarbone in TT practice) and he won the Junior TT and Ulster events, Foster won the Belgian, Ken Bills the Dutch and David Whitworth came second in the Swiss Grand Prix, which was the only 350cc event that they did not win that year. In the five classical events there were a total of 30 "places" giving Championship points, and Velo took 18 ; an altogether good year. The 500 model saw little action that season.

For 1949 the racing department brought out new 350 and 500cc models — both with dohc heads. With large GP carburetors (1-5/32" and 1-5/16"), the twin-cam racers proved very fast. Frith won every 350cc classical race, with other Velo riders gaining many second through sixth places. The 500 did not fare too well as the emphasis was then on the 350 class; a third (Ernie Lyons) in the Senior TT and a fifth (Frith) in the Swiss GP was the best obtained.

In 1950 Bob Foster carried on the winning tradition (Frith had retired) and he was crowned World Champion after great victories in the Belgian, Dutch and Ulster classics plus a second in the Swiss event. Bob had tough luck in the Junior TT when he was forced to retire with a broken rear brake rod after becoming the first to break Stanley Woods' 1938 lap record. The big 500 saw little action, with only a sixth place by Reg Armstrong in the Senior TT.

In 1951 the factory surprised all by adding a new dohc 250cc model to the works team, and by dropping the venerable old 500. Velos ridden by Foster, Bill Lomas, Cecil Sandford, Tommy Wood and Les Graham carried on the battle, but the old enthusiasm for racing was slowly slipping away. Lomas and Foster took fifth and sixth in the Junior TT, Wood won the Spanish with Graham second, Lomas and Sandford took third and fourth in the Belgian, Graham won the Swiss event with Sandford second, private owners took fifth and sixth in the Dutch; and Norton regained the 350cc World Championship. The little 250 took fifths in the IOM, Swiss, French and Ulster events, plus a third in the Ulster. Then, at the end of the year, it was announced that the KTT was no longer to be produced. The factory made one last feeble effort in 1952 with Les Graham taking a fourth in the 250cc TT plus a few "places" in the 350 class. Then, it was all over — a great chapter in motorsport was ended.

But if the racing game was all finished at Hall Green it was apparent that the standard production range was not — for the Velo has shown a vigorous growth in quality since then. In 1951 the MAC was improved by using a telescopic front fork of their own manufacture. In 1952 an alloy head and cylinder were fitted, and the swing-arm frame was adopted in 1953. Then, in 1954, the "alloy" MSS was re-introduced with engine dimensions of 86 x 86mm. The scrambler model was added in 1955, and in 1956 the Viper and Venom high performance sports roadsters made their debut ; one of these becoming the first motorcycle to average 100 mph for 24 hours. Then lastly there is the Valiant, a 200cc ohv sports version of the gentlemanly 200cc LE model.

The past few years the Velo has done exceptionally well in European production machine racing, generally dominating the 500cc class, and so for 1965 a "Thruxton" model was added to the range to satisfy the demand for a sports-racing machine. The Thruxton has already established a splendid reputation, and is noted for its reliability at speed over long distances, powerful brakes and super-fine handling.

So this, then, is the story of the "Velo," a marque that has a worldwide reputation for integrity of engineering based upon many glorious years on the world's great race courses. Long may we see the loyal riders of these magnificent singles ; it's the last of the breed, really.