GREEVES

HISTORY

A saga rich in honor.

GEOFFREY WOOD

THE HISTORY of a motorcycle manufacturing company has often begun in some unusual ways, but the establishment of Greeves is unique. The manufacturing of a gasoline engine powered wheelchair for severely disabled people may not seem to be the way to start a motorbike business, but, nevertheless, that is exactly how one Britisher made his mark in the world of two-wheeled sport.

What is truly unique about this venture is that today, despite its ancestry of a motorized wheelchair, the Greeves concern produces nothing but fire-breathing competition machines that are definitely not for the faint of heart. From wheelchairs to motocross championships is their motto, and what fabulous results have been obtained for such a tiny manufacturer!

The story of this venture began in 1945 when Derry Preston Cobb, who now is sales manager of the Greeves concern, complained to his cousin, Bert Greeves, that his battery powered invalid car was hopelessly inadequate for getting about the countryside. To Bert Greeves this was a challenge, particularly after Derry put a 30-cent wager on the deal, so he went to work designing and building the rig. The result was surprisingly good, so the pair of them decided to go into business producing the machine.

The little business prospered and the tale might have ended there had it not been for the creative genius of Greeves. Now Bert was, and still is, a dyed-in-the-wool motorcyclist, having been a rider since 1919 when, as a 14-year-old, he began his studies on a 225-cc James. Today there are 15 bikes in his garage, ranging from a 1912 Triumph to a 1951 Vincent "Black Shadow" that still is known to occasionally travel down the Southern Arterial at well over the 100-mph mark.

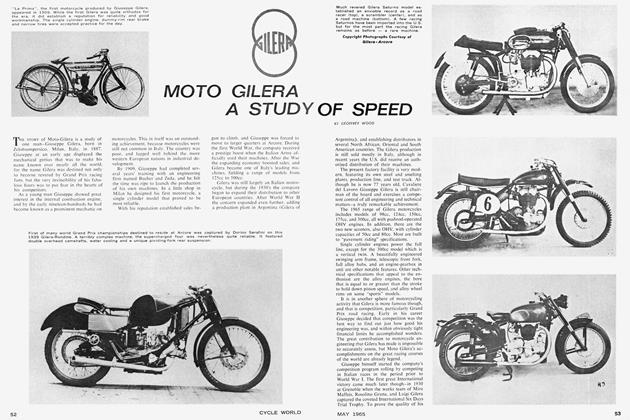

So Bert Greeves is, above all, a dedicated motorcyclist, and it was only natural that someday he would get the desire to build his own motorbikes. In the early 1950s, he got down to the designing and testing of his theories, and in the 1953 Earls Court Show the first models were put on display. Delivery was promised in early 1954, and the two models certainly whetted the appetites of the sporting minded riders.

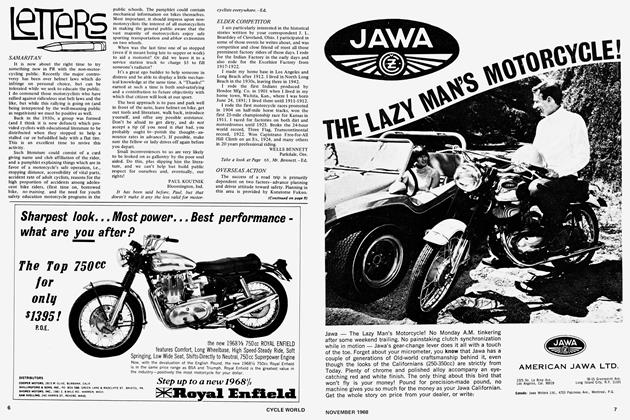

These first Greeves motorbikes used the popular 200-cc Villiers engine, a common practice in those days among a host of British manufacturers. The two models were for competition-one was a trials mount, the other a scrambler. Powerplants had bore and stroke of 59 by 72 mm, and they were the tried and proven two-stroke design. Both models featured four-speed gearboxes, with the scrambler having a close ratio box and the trials model having wide ratio gears.

It was in the chassis and suspension that Bert manifested his theories, and even today some of the basic ideas are retained. The model 20-S motocross machine was particularly cobby looking with its leading-link front fork, unusual swinging-arm rear suspension, and I-beam front downtube frame member.

The front fork featured an unusual rubber suspension with friction dampers, and the suspension characteristics were quickly adjustable at trackside to suit local conditions. The rear suspension system was a very early attempt at the swinging-arm principle, and it used spring loaded units with friction pads for damping. The massive I-beam frame member was cast of magnesium alloy, for light weight with great strength.

The rest of the specifications were functional. A short open exhaust pipe was used, and the alloy fenders were mounted well above the tires for plenty of clearance on suspension and for mud clinging to the tires. A small fuel tank was used, and the seat was the now common dual type.

The trials model was similar to the scrambler, except it had an upswept exhaust pipe with muffler, a speedometer, and trials tires instead of the gripster tread. The trials model was very light, and its handling in rugged going was considered to be exceptional.

After introduction of his bikes, Bert Greeves set about improving the breed. During those years, the world's manufacturers all were experimenting with some sort of rear suspension, and Greeves was one of them. That was the era when many were changing from the rigid frame, or plunger suspension, to the now common swinging-arm type, and Greeves decided to join the throng.

The new frame used Girling telescopic shock absorber units, and it followed accepted practice in its basic design. The unusual leading-link front fork was retained, however, but it was modified for better suspension characteristics. All in all, the Greeves was a good little bike, but it was still barely known outside England.

About that time, Bert decided that, if his name were to grow, he would have to gain some publicity. If sales could be increased, there would be more profits for research and development, and this would provide a better bike that would sell in greater numbers. There were several avenues open for promotion of the Greeves, but the sporting nature of the designer made the competition route the only logical answer.

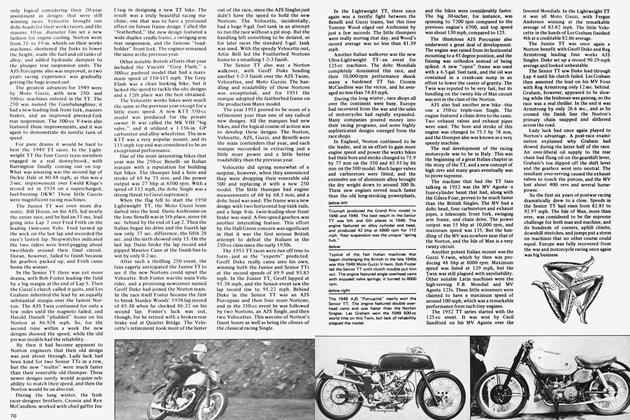

To proceed in this direction required a top flight rider, as those were the days when motocross racing was becoming immensely popular in Europe. Bert obtained the great rider he needed. To the late Brian Stonebridge goes a great deal of credit for putting the marque in the news. Brian was a truly fine motocross rider, with a wealth of both British and continental experience to bring to the tiny factory.

So, in January of 1957, a great partnership was formed, and the pair forged ahead in racing and improving the scrambler breed. During 1957, Stonebridge concentrated on British events, winning his share and establishing a fine reputation for the eager young company. All this activity and success naturally helped the sales of the company's product, and the future looked bright.

In 1958, the Federation Internationale Motorcycliste (FIM) decided to establish a Coupe d' Europe trophy for 250-cc class motocross machines, and a series of races were scheduled in various countries throughout Europe. Stonebridge was anxious to enter this series, as he had a great wealth of continental experience upon which to base his campaign. Bert was also agreeable to the idea, because no British lightweights at that time were capable of upholding British prestige.

So the still tiny company embarked enthusiastically on its giant-killing mission, and what a battle it was. All season long the lanky Stonebridge battled it out with the best that the world had to offer, and in the end he came 2nd to Jaromir Cizek on his flying Jawa. The season's tally also gave a big boost in Greeves motorcycle sales. The company was on its way!

The following year proved to be another battle all season long for Stonebridge, and again he garnered a 2nd place in the championship standing. That year, the Britisher had the satisfaction of trouncing his Czechoslovakian rival, only to lose out to Rolf Tibblin (Husqvarna). The success and publicity that Stonebridge gained continued to help expand Greeves sales, and for the first time the export business became important to the company.

Meanwhile, the founder had been busy at his drawing boards. One of the most important advances was the new 66-mm bore cylinder to boost the Villiers engine from 197 cc to a full 246-cc powerplant. This was followed by a new head, and these two components gave the engine a square appearance. A systematic development of port shape and exhaust tuning also yielded an increase in horsepower, which was essential to keep up with the fast charging continentals.

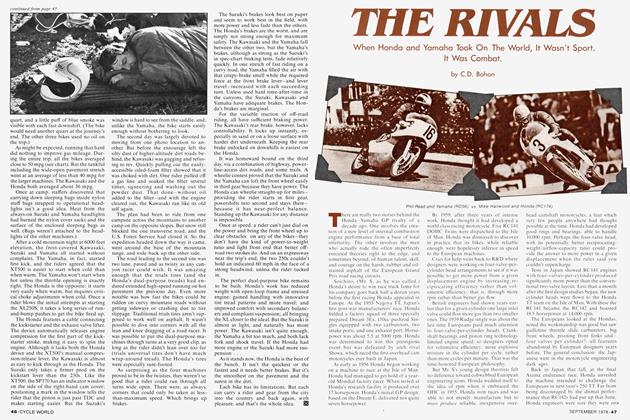

The following year saw a new name on the works machines, as Brian Stonebridge had tragically lost his life in an automobile accident. The new ace was Dave Bickers. His forceful riding was destined to be the second great chapter in the story of the Greeves.

During 1960 and 1961 Bickers rode a greatly improved machine with such gusto that he was crowned European champion both years. These magnificent results really put the seal on the reputation of the marque, and sales rapidly expanded. Exports also increased until 20 percent of the total production was leaving the mother country to do battle all over the world.

With such fabulous international competition success it was only natural that the factory would expand its production into the roadster field. The 1962 catalog, for example, listed a total of 11 models-four roadsters and seven competition machines. The roadsters included 200and 250-cc Singles, and a 325-cc Twin-all with standard Villiers engines. All the road models featured the proven I-beam front frame member and the leadinglink front fork.

The seven competition models were all 200and 250-cc single-cylinder trials and

motocross mounts. Both were available with either the stock Villiers engine or with the more potent Greeves alloy cylinder and head components. These competition machines established a great reputation all over the world in the hands of private owners, and the sales of the company continued to expand.

All this activity in the engineering department curtailed the international competition program, and Bickers was able to compete in only the British round of the 250-cc series. Dave did win that event, though, just to show that the marque had lost none of its touch.

For 1963, the range of machines offered was expanded into a new area, but the number of models offered was reduced to nine. The roadsters were all 200and 250-cc Singles, and they were little changed from the previous year. The two 250-cc trials models were identical except for engines-one with a standard Villiers engine, the other with a Greeves alloy cylinder and head. The trials models featured wide ratio gearboxes with ratios of 7.75:1, 10.5:1, 18.6:1 and 27.9:1.

Two scramblers were offered that year, and both were similar except for engines. The Hawkstone model used a Villiers Mark 36-A engine that developed 19 bhp at 5500 rpm. Dry weight was 223 lb. The Moto-Cross model used the Greeves square alloy head and cylinder on the Villiers crankcase, and it produced 23 bhp at 6000 rpm. The compression ratio was 12.7:1 as compared to 10.5:1 on the stock engine, and both had gear ratios of 10.0:1, 12.7:1, 17.8:1, and 25.0:1.

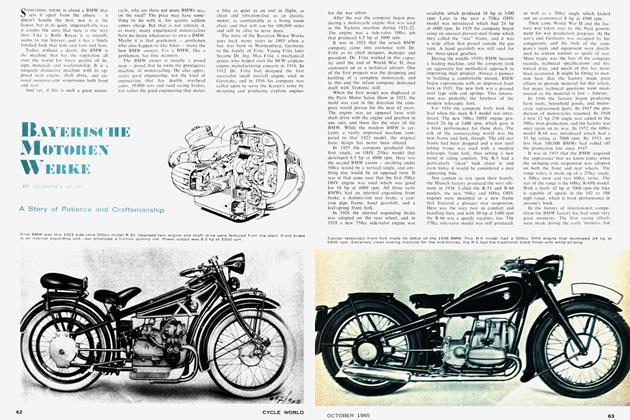

Probably the most talked about Greeves that year was the new Silverstone road racing model. The inexpensive racer was produced for the private owner who had to watch his expenses very carefully, and yet the bike was capable of an outstanding performance.

The frame of the Silverstone was based on the successful motocross model, but with small modifications to make it suitable for road racing. The wheels had alloy rims laced on full width cast alloy hubs, and the tire sizes were 2.75-19 front and 3.25-18 rear. A sleek 2.75-gal. fiberglass fuel tank was fitted, and an orthodox road racing seat was used.

The engine was a modified Villiers 250-cc unit with the Greeves alloy head and cylinder. Modifications to the port sizes and location combined with an expansion box exhaust system provided a power output of 26-27 bhp at 7500 rpm. The power spread was quite wide, with good punch coming in at 3000 rpm.

During 1963, the company was engaged in a great deal of development work, and the success in international motocross was not quite so great as in previous years. The continental machines were getting faster and the competition had become intense. The continued development work on the Villiers engine was paying off in horsepower, but the added stress on the lower end and gearbox was causing a notable increase in mechanical failures. By then it was obvious to Greeves that piecemeal modifications were no longer good enough-a whole new engine was needed.

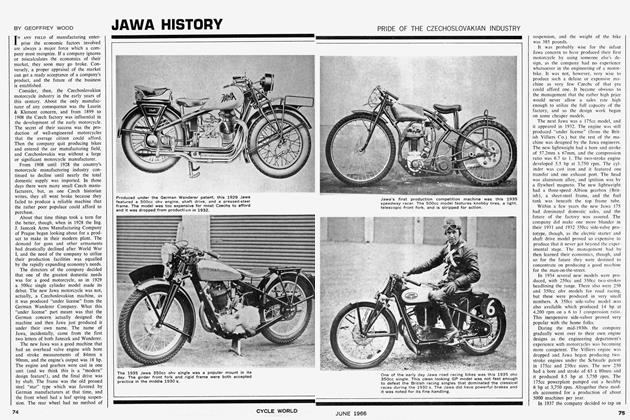

During late 1963 and early 1964, the creative genius of Bert Greeves was hard at work. By March of 1964, the world got a taste of things to come when the new "Challenger" scrambler model was introduced, and this was followed in late summer by the Silverstone Mark II road racing model. Both of these bikes featured the "all Greeves" Challenger engine. In time, the complete range of models offered was to use this engine.

The lower end of the Challenger engine was a compact built-up unit made by the famous Alpha Co. The crankpin was pressed into the flywheels and an orthodox roller bearing rod was used. The alloy cylinder and head were made by Greeves, and these new components had a 50 percent greater cooling area than did the earlier Villiers-Greeves engine.

A great deal of experiment went into the port shape and location on the scrambles and road racing engines, and in the end both units produced power characteristics well suited to the tasks at hand. The motocross model breathed into the crankcase through a 1.187in. Monobloc carburetor while the Silverstone used a huge 1.375-in. Amal GP type. Both engines had the intake port inclined-the road racer 22 degrees and the scrambler only 8. Both intake systems are inclined another 9 degrees by the forward tilting of the engine in the frame.

For a gearbox, Greeves went to the famous Albion concern, which designed a rugged four-speed transmission for the scrambler and a new close ratio five-speed unit for the Silverstone model. The frames remained much the same as in previous years.

These new Challenger engines were considerably more powerful than the previous Villiers-Greeves units, and the reliability was also notably improved. The scrambles model produced 25 bhp at 6000 rpm, combined with good torque at anything above 3000 revolutions. The Silverstone engine produced 30 bhp at 7500 rpm after a full 5 min. at full throttle on the test bench. The engine would pull 33 bhp for a brief flash reading, but the inevitable 10 percent loss after the engine was hot was a truer indicator of actual track performance.

So, out into the world went the new Challengers. They became a smashing success! There were naturally a few minor problems to sort out, but the basic design seemed to

perform well in addition to being reliable. Dave Bickers continued to mop up in the home country motocross events, and his sashays on the continent were treated with profound respect by his rivals.

Meanwhile, the Silverstone model also was distinguishing itself. Earlier in the year, Joe Dunphy had garnered the first points ever won by a Greeves machine in world championship road racing when he took a 5th in the 1964 Day tona classic. This was followed in September by the smashing victory of Gordon Keith in the 250-cc Manx Grand Prix. Gordon's average speed in this race for "amateurs" on standard production racing machines over the famous Isle of Man course was a speedy 86.19 mph.

With all this fabulous success in both motocross and road racing events, it was only natural that Greeves sales continued to expand. Exports in particular grew in importance, as the fame of the British two-stroke spread all over the world. And, with Don Smith's winning of the European Trials Championship, the marque was acquiring an outstanding reputation as a trials machine.

For 1965, the range of Greeves machines was narrowed to seven models—four competition mounts, and three roadsters. The roadsters were a 200-cc Single and a pair of 250-cc Twins—all with standard Villiers engines. The low priced 250-cc trials model also used a Villiers engine, and this dirt plugger was popular in the hands of private owners for club trials and competitions.

For the real enthusiast, the three pur sang competition mounts were the only thing. First was the "Scottish" trials model with a Villier s-G reeve s engine, and this model was establishing an outstanding reputation in international trials. Then there were the powerful Challenger scrambles model for motocross racing, and the Silverstone road racing machine.

The record chalked up in 1965 by the small British marque again was impressive. After a rather frustrating time in getting the bugs worked out of his motocross bike, Dave Bickers had a serious bash at the 1965 world motocross title. The season proved long and torrid, with Dave coming home 3rd in the championship standings behind Victor Arbekov and Joel Robert on their potent CZs. Dave did have the satisfaction of winning the British 250-cc title for the fifth time, though, and all this helped give the name even greater renown.

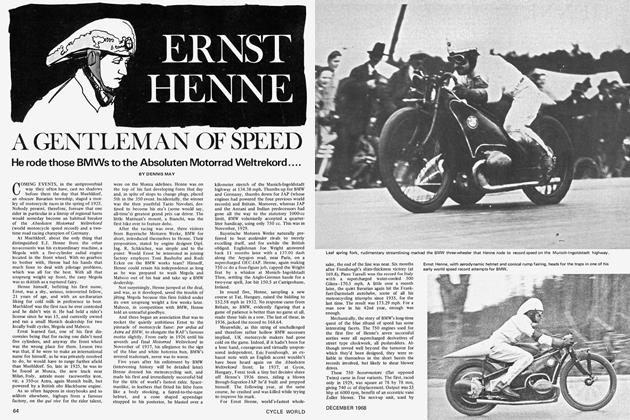

In road racing, the Silverstone acquitted itself most admirably, with Greeves taking 1st and 3rd in the 1965 Manx Grand Prix classic. The winner was Dennis Craine at the record average of 88.37 mph, and a new lap record was chalked up to the tune of 89.84 mph. This win, combined with the many victories on local race courses all over the world, certainly accomplished what Bert Greeves had set. out to do-build a good and inexpensive racer for the private owner.

During 1966, the factory reduced its range to only five models, but those that remained were all notably improved. These five were a 250-cc trials model, a 200-cc single-cylinder roadster, a 250-cc twin-cylinder road model, the 250-cc Challenger scrambler, and the Silverstone road racer. The rubber suspension front fork, so long a Greeves trademark, finally gave way to a leading link front fork with Girling hydraulically damped spring suspension units. There were other less noticeable changes made to the five models, and a new 360-cc motocross machine also was in the experimental stage.

During 1966, the company lost the services of Dave Bickers who had joined the CZ camp, but newcomer Freddie Mayes pipped Dave by one point to give Greeves its sixth British 250-cc scrambles championship. On the continent, the marque faired less well, as Greeves had no riders with the necessary experience to challenge the top European aces. In the trials sphere, the marque was kept well to the fore by Don Smith, who again won the European Trials Championship.

Meanwhile, the design improvement work went on, but for 1967 the range of models offered was reduced to only four. All of these were competition machines-the company had decided to specialize on the sporting end of the game. The first model was the 250-cc Anglian trials mount, which could be had with either a Greeves or Ceriani front fork.

This machine was a replica of the works bike used by Don Smith-who since has joined the Montesa factory-and it offers the mud-pluggers a truly competitive mount.

Next in line was the 250-cc Challenger scrambler, which had a new frame and redesigned four-speed gearbox. The weight was a light 217 lb. and the wheelbase was 51.5 in. A new 1.75-gal. fiberglass fuel tank was used, and the Greeves-made front fork used Girling shock absorber units.

The 360-cc Challenger is the model that excited the motocross riders, and this mount also could be obtained with either a Greeves or Ceriani front fork. The powerplant featured a bore and stroke of 80 by 72 mm. Compression ratio was 10.0:1. The weight of the 360-cc model was very light at 226 lb. and the wheelbase was 54.5 in.

The Silverstone model also was continued with minor modifications, with its power output fractionally increased. Maximum speed with a fairing was not far shy of the 120 mph mark, which was really tramping for a production 250. Peak power was reached at 8000 rpm, and the acceleration through the five speed gearbox was competitive on the short British racing circuits.

Then, after gradually reducing the number of models offered, Greeves came back with something of a bombshell for 1968, announcing an eight-model range which included an all-new 350-cc road racer. Named the Oulton in honor of a British race circuit, the 350 was developed from the 360-cc scrambler. Its piston displacement of 344.3 cc is achieved by retaining the motocross engine's 80-mm bore, while a special crankshaft provides a stroke of 68.5 mm. Traditional Greeves design appears in the leading link front fork, and alloy beam front down tube on the frame.

Other new models include two machines intended mainly for export to the U.S. One is the 250-cc Ranger trail bike, the other is a special TT racer based on the Challenger. Also new is a Wessex trials bike, equipped with an all-Villiers 250-cc power unit. The idea behind this machine is to offer a low priced machine for novice and less serious riders. The 250-cc Challenger motocross model featured a modified short stroke engine. Anglian, Silverstone, and Challenger 360 models continue almost unchanged.

On motocross circuits, the company has not maintained its devastating success of previous years. Leading factory riders now are two dashing young men, red-haired Arthur Browning, and crewcut Bryan Wade. Both are competitive on English circuits, but the company only rarely ventures to the continent now. However, latest developments at the factory are a 390-cc version of the 360 engine, in an attempt to keep pace with the ever growing displacements of Continental two-stroke Singles, and an experimental alltubular frame. Both could land the team right back in the forefront of international competition.

So, this is the story of the Greeves-a modern day legend of a man very dedicated to the motorcycling sport. In this age of mass production it is refreshing to find such interesting personalities and down to earth machines, and one cannot help but admire the men who have achieved so much with so little behind them. Today the Greeves still is comparatively small in the production of motorbikes, but to many motorsportsmen the world over, the name means a great deal. From wheelchairs to motocross-it is a saga rich in honor.