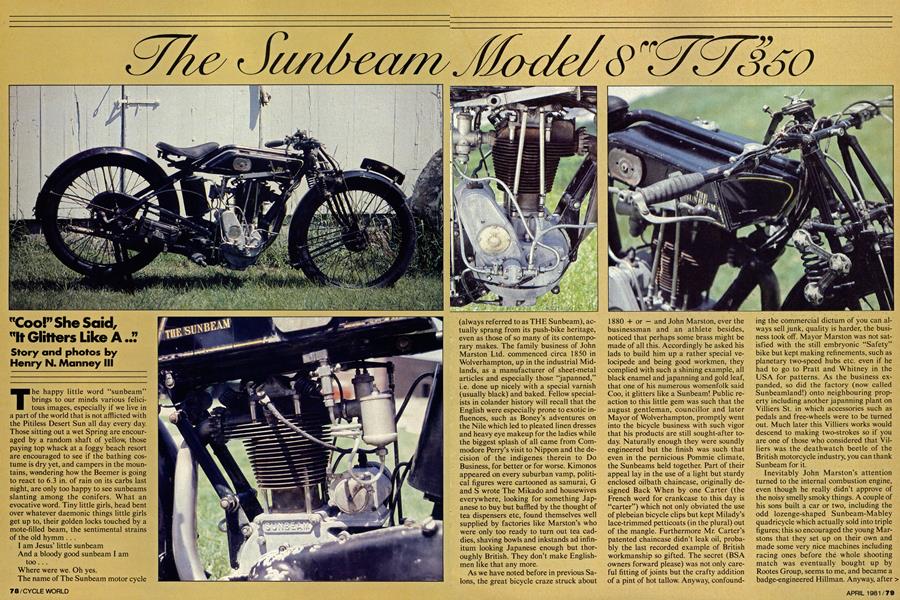

The Sunbeam Model 8"TT"350

"Coo!" She Said, "It Glitters Like A..."

Henry N. Manney III

The happy little word "sunbeam" brings to our minds various felicitous images, especially if we live in a part of the world that is not afflicted with the Pitiless Desert Sun all day every day. Those sitting out a wet Spring are encouraged by a random shaft of yellow, those paying top whack at a foggy beach resort are encouraged to see if the bathing costume is dry yet, and campers in the mountains, wondering how the Beemer is going to react to 6.3 in. of rain on its carbs last night, are only too happy to see sunbeams slanting among the conifers. What an evocative word. Tiny little girls, head bent over whatever daemonic things little girls get up to, their golden locks touched by a mote-filled beam, the sentimental strains of the old hymm .. .

I am Jesus’ little sunbeam And a bloody good sunbeam I am too...

Where were we. Oh yes.

The name of The Sunbeam motor cycle (always referred to as THE Sunbeam), actually sprang from its push-bike heritage, even as those of so many óf its contemporary makes. The family business of John Marston Ltd. commenced circa 1850 in Wolverhampton, up in the industrial Midlands, as a manufacturer of sheet-metal articles and especially those “japanned,” i.e. done up nicely with a special varnish (usually black) and baked. Fellow specialists in colander history will recall that the English were especially prone to exotic influences, such as Boney’s adventures on the Nile which led to pleated linen dresses and heavy eye makeup for the ladies while the biggest splash of all came from Commodore Perry’s visit to Nippon and the decision of the indigenes therein to Do Business, for better or for worse. Kimonos appeared on every suburban vamp, political figures were cartooned as samurai, G and S wrote The Mikado and housewives everywhere, looking for something Japanese to buy but baffled by the thought of tea dispensers etc, found themselves well supplied by factories like Marston’s who were only too ready to turn out tea caddies, shaving bowls and inkstands ad infinitum looking Japanese enough but thoroughly British. They don’t make Englishmen like that any more.

As we have noted before in previous Salons, the great bicycle craze struck about 1880 + or — and John Marston, ever the businessman and an athlete besides, noticed that perhaps some brass might be made of all this. Accordingly he asked his lads to build him up a rather special velocipede and being good workmen, they complied with such a shining example, all black enamel and japanning and gold leaf, that one of his numerous womenfolk said Coo, it glitters like a Sunbeam! Public reaction to this little gem was such that the august gentleman, councillor and later Mayor of Wolverhampton, promptly went into the bicycle business with such vigor that his products are still sought-after today. Naturally enough they were soundly engineered but the finish was such that even in the pernicious Pommie climate, the Sunbeams held together. Part of their appeal lay in the use of a light but sturdy enclosed oilbath chaincase, originally designed Back When by one Carter (the French word for crankcase to this day is “carter”) which not only obviated the use of plebeian bicycle clips but kept Milady’s lace-trimmed petticoats (in the plural) out of the mangle. Furthermore Mr. Carter’s patented chaincase didn’t leak oil, probably the last recorded example of British workmanship so gifted. The secret (BSA owners forward please) was not only careful fitting of joints but the crafty addition of a pint of hot tallow. Anyway, confounding the commercial dictum of you can always sell junk, quality is harder, the business took off. Mayor Marston was not satisfied with the still embryonic “Safety” bike but kept making refinements, such as planetary two-speed hubs etc. even if he had to go to Pratt and Whitney in the USA for patterns. As the business expanded, so did the factory (now called Sunbeamland!) onto neighbouring property including another japanning plant on Villiers St. in which accessories such as pedals and free-wheels were to be turned out. Much later this Villiers works would descend to making two-strokes so if you are one of those who considered that Villiers was the deathwatch beetle of the British motorcycle industry, you can thank Sunbeam for it.

Inevitably John Marston’s attention turned to the internal combustion engine, even though he really didn’t approve of the noisy smelly smoky things. A couple of his sons built a car or two, including the odd lozenge-shaped Sunbeam-Mabley quadricycle which actually sold into triple figures; this so encouraged the young Marstons that they set up on their own and made some very nice machines including racing ones before thé whole shooting match was eventually bought up by Rootes Group, seems to me, and became a badge-engineered Hillman. Anyway, after some prompting from the kids on how motorcycles were not necessarily for the lower orders, old John gave in and hired the august John Greenwood, ex-Rover and J.A.R (they supplied about half of the engines built at that time), to design him something in keeping with Sunbeam’s exalted reputation. In short, a Gentleman’s Motorcycle. Elegance, Silence, Reliability, Finish. A tall order for now, let alone 1911, but soon the 349cc flathead Single, largely hand-built by Harry Stevens of the AJS Stevens family, emerged to great acclaim. It didn’t leak, either, but John Marston, who never rode a motorcycle in his life, looked and said “That magneto in the front of the cylinder will get wet. Put it in back.”

The same sort of folks who bought Sunbeam velos also graduated up to Sunbeam motorcycles, bringing with them a coterie of riders who were weary of crude and unreliable machinery. Of course the slow development of early electrics, early tyres, early steels early everything at this time perforce made any sportsman’s progress a trifle uncertain but careful assembly did help a lot, as well as use of sound engineering practice like the Little Oil Bath chain case. Belt-drive on most motorcycles conversely carried on till well after the Kaiser War as did flathead engineering, well after the dohc Peugeots had run on Grand Prix circuits. Sunbeam gradually improved their wares, using mostly proprietary engines (bought-out) up till 1922 about, but the death of John Marston and several of his children in a ’flu epidemic just after the war brought major changes. To meet “death duties” (i.e. inheritance tax) the factory had to be sold to a consortium of explosive manufacturers who soon amalgamated with Nobel Industries, of Nobel Prize fame. Therefore a lot of fresh capital became available, something lacking before, and design work went forward, prodded by George Dance, the famous “sprinter” of the day. Profiting from the new metallurgy spawned by the War, George made use of forged alloy pistons and even fabricated a detachable hemihead on what had been so far an integral head-and-barrel sidevalver. While this was under development, the factory’s runners (Dance dnf) finished 1st and 3rd in the 1920 Manx TT, piddled away their chances in ’21, and scored again in 1922, with the famous Alec Bennett, riding (I think) the famous Longstroke that was the linchpin of the firm’s fortunes. His mount was the last sidevalver to win the TT, coincidentally in the same year that the first ohv Norton appeared.

Change was in the wind and for 1923 a new “23/4 hp” (fiscal rating) 350 appeared, the model from which the subsequent ohv bikes derived. Most English factories seem to concentrate on 350s, much cheaper to tax and run, and the ohv’s duly arrived in this new form only to fall flat on their faces in the TT with what were described as teething troubles. No better luck in the Senior, for which the 350s did double duty, but as a consolation George Dance had led in the Junior until the last lap. A shakeup was in order so the experienced Graham Walker, later Editor of the “Motorcycle”, was hired as team manager. A new production range resulted, based on the 70 x 90 mm ohv 350, which featured such niceties as dry sump lubrication instead of the former splash, a hemi head with large valves (you could see straight through the inlet port out the exhaust) and a trick bifurcated front downtube to avoid drastic curves in the pipe. The front brake was enlarged a bit and other items tidied up. There was no official entry in the TT for 1924 as the bikes weren’t ready yet. Len Randles did win the fall Manx GP on one. However the factory team raced on the Continent, such as the GPs of Italy, Austria, Switzerland, Hungary, and Germany with quite a bit of success and in addition a French private owner won the 24 hr. Bol d’Or near Paris. These bikes were really Sunbeam’s last clap as the following year, an abortive ohc design didn’t work out at all and put the racing program on the well-known slippery slide.

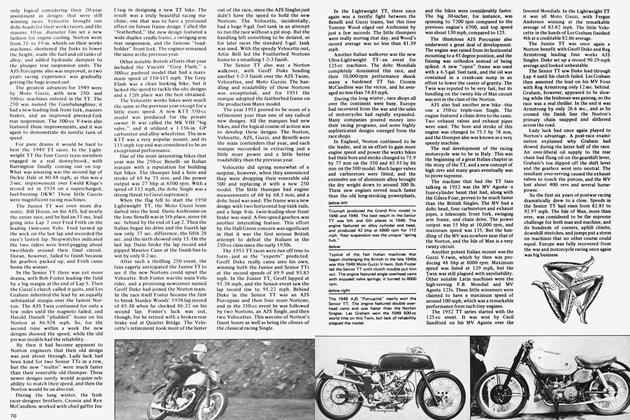

The subject of our Salon is thus one of these 1924 Model 8 “TT” 350s, owned by Keith Hellon of Libertyville, 111., which came to light along with its Model 9 500 brother in a rather complicated trade with an Italian ex-racer. Both bikes were shipped down there in 1925 to run in the Italian GP, at a guess, and afterwards “were given to the mechanic” and vanished into a garden shed. It will be remembered that the celebrated Italian racing driver, Achille Varzi, was actually a factory rider for Sunbeam at that time (he later drove for Bugatti, Alfa Romeo, Auto-Union etc.) but we think it more likely that the bikes went to Sunbeam agent Ernesto Valiati, who had such aces as Varzi, Arcangeli, Ascari and even Nuvolari riding for him at various times. Unfortunately we don’t have the right book to look up the results and history of that era as it would be fascinating. Racing motorcycles was the accepted way of graduating to Grand Prix cars in the 20s and 30s and too bad they don’t have to today.

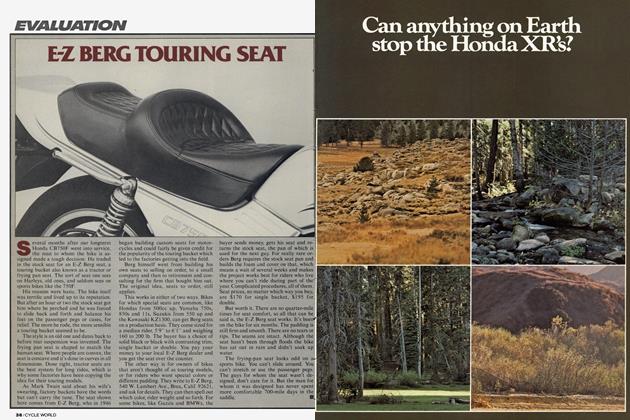

What we have here, then is a motorcycle of considerable importance, both mechanically and as a bridge between old and new technology. The 70 x 90mm engine, somewhat less than square as gummint taxation penalised big bores, was actually quite modern for its day with drysump lubrication and then reverted to vintage with grease nipples on the valve rockers! As with many of the bikes of this period the valve gear sat out in the open, not necessarily because of ease of tappet adjustment but because valve springs were thought to need the blast of cooling air. Velocette was one of the first to enclose theirs in little dog kennels and ES in Norton ES 2 actually meant Enclosed Spring. Manx Nortons kept theirs outside until the end, and a fine lot of oil they sprayed around too. Mousetrap valve springs were also fitted for cooling reasons as well as easy replacement; only one per valve were used in line with some theory of George Dance’s about reciprocating weight which is okay until your one spring breaks and the valve falls in. Typical of the period, the hefty crankcase and primary drive case as well as the jampot silencer were all alloy but head and cylinder remained resolutely iron, apparently because the poor fuels of the day required more heat retention. Even with alky fuels the racers don’t seem to have gone to alloy heads much: perhaps the alloy available wasn’t suitable. Much later Norton was still shrinking bronze “skulls” into aluminum heads and several makes, including Rudge, used a head made wholly of bronze. What the compression ratio was we have no idea but bikes of the period ran about 5.5:1, a good thing as the engine was held together by four really long studs of none too spectacular a diameter. The exhaust pipe exited through a handy place in the front downtube (later two-port versions had a normal frame) which nailed itself to the crankcase, thus being one of the first to use the engine as a stressed member. Flat tankers like this also had a double top tube, one detachable, and there were few complaints about the handling but current reports say that this innovation to accommodate the exhaust pipe certainly didn’t help much at high speed. The rear of the wellmade and substantial frame was secured by a massive casting under the tiny threespeed gearbox (4.9, 7.4, 11.4) which couldn’t have done the ptw ratio any good while the front was looked after by period Webb forks with curious low-mounted springs on each side and friction dampers. Up on top of the flat tank with its cutouts for steering lock (so what is new?) lived a gigantic butterfly steering damper which, one imagines, was screwed down tight over the bumps.

continued on page 201

continued Jrom page 80

There are lots of nice touches. The Webb brakes, such as they are, have leading and trailing shoes each, featuring a combination of cable and rod operation, the neat cast-in platform for the EIC magneto, and the proliferation of little plaques stating that the bike was indeed The Sunbeam. I like also the fancy oil pump on the engine’s right side, a two-part one with one side feed, one side scavenge, a forest of little pipes and the whole thing adjustable via a little wheel and pointer. To make the driver’s life easier, an oil pressure button on the plunger pump comes out when pressure is available and then if there is any doubt, the fancy filler on the oil tank can be peered into. The 3xh OH Amal (about 1 inch) is available as well without moving much, the comp release shifts the cam instead of just opening a hole, and for those of you allergic to Ferodo, the primary case holds a leather clutch.

It is those flat handlebars, though, with long graceful levers that are the essence of Vintage motorcycling. The long inverse levers control the clutch and front brake respectively while on the left the upper long Bowden lever controls advance/retard and the other compression. The bulb horn is missing. On the right, the upper long Bowden lever is the strangler (or choke) while the lower one controls throttle. Pretty exciting on a cold morning with gloves. I think this Model 8 came before kickstarters were invented, hence the front and rear stands. Tyres were (front) Pirelli cord 26 x 2.5, probably fitted in Italy, while the back is a K 57 Dunlop cord 26 x 2.5, possibly original. The original George Dance rubber knee-grips are no more but as compensation, the spring saddle has leaf springs no less. What fun!

A little research into the bike turns up some mysteries. The motor number, 229 237, is all right for the Model 8 but either shows a Model 8 number for 1926 approx or else has a trick Model 10 “Sprint” engine from 1925. The Sprints are very rare, with a slightly different frame incorporating a distinctive pointed tank, and as factories like Sunbeam tended to race slightly modified customers’ equipment, it would figure that a trip to Italy for a race would justify a bit of fiddling. The bike has run, but was full of old gas when we saw it, and apparently has compression and all those good things in spite of being completely unrestored aside from the removal of layers of Lombardy dust. Mr. Helion also owns a Model 9/11 500, somewhat less complete, and thus has all sorts of Sunbeams shining in his garage. This, then, was the state of the art in 1925. Fascinating. ®