The Isle of Man TT, Part II

only logical considering their 20-year investment in designs that were still winning races. Velocette brought out dohc heads for their works racers, and the massive 10-in. diameter fins set a new fashion for engine cooling. Norton went from 21to 19-in. wheels on their works machines, shortened the forks to lower the height, made the fuel and oil tanks of alloy, and added hydraulic dampers to the plunger rear suspension units. The AJS Porcupine also was improved, as two years racing experience was gradually getting the bugs ironed out.

The greatest advances for 1949 were by Moto Guzzi, with new 250and 500-cc machines entered in the TT. The 250 was named the Gambalunghino; it had a new leading-link front fork, massive brakes, and an improved pivoted-fork rear suspension. The 500-cc V-twin also featured these improvements, and it was again to demonstrate its terrific turn of speed.

Por pure drama it would be hard to beat the 1949 TT races. In the Lightweight TT the four Guzzi team members engaged in a real donnybrook, with Barrington finally coming out on top. What was amazing was the second lap of Dickie Dale at 80.44 mph, as this was a 2-sec. improvement over Lwald Kluge’s record set in 1938 on a supercharged, fuel-burning DKW! These little Guzzis were magnificent racing machines.

The Junior TT was even more dramatic. Bill Doran, on his AJS, led nearly the entire race, and he had an 1 1 -sec. lead going into Lap 7 over Fred Frith on the leading twin-cam Velo, bred turned up the wick on the last lap and recorded the race’s fastest lap. Stopwatches indicated the two riders were level-pegging about two-thirds around their final circuit. Doran, however, failed to finish because his gearbox packed up, and Frith came home the winner.

In the Senior TT there was yet more drama, with Bob Foster leading the field by a big margin at the end of Lap 5. Then the Guzzi’s clutch called it quits, and Les Graham inherited the lead by an equally substantial margin over the fastest Norton. The AJS Twin continued for only a few miles until the magneto failed, and Harold Daniell “plodded” home on his Norton at 86.928 mph. So, for the second time within a week the new designs showed the speed, while the old prewar models had the reliability.

By then it had become apparent to Norton engineers that their old design was just about through. Lady luck had been kind for two Senior TTs in a row, but the new “multis” were much faster than their venerable old thumper. These newer designs surely would acquire reliability to match their speed, and then the Norton would be an also-ran.

During the long winter, the Irish racer-designer brothers, Cromie and Rex McCandless, worked with chief gaffer Joe Craig in designing a new TT bike. The result was a truly beautiful racing machine, one that was to have a profound effect on future frame design. Called the “featherbed,” the new design featured a wide duplex cradle frame, a swinging arm rear suspension, and the famous “roadholder” front fork. The engines remained the same as the previous year.

Other notable British efforts that year included the Vincent “Grey Flash,” a 500-cc pushrod model that had a maximum speed of 110-115 mph. The Grey Flash was a clean looking bike, but it lacked the speed to tackle the ohc designs and a 12th place was the best obtained.

The Velocette works bikes were much the same as the previous year except for a little more speed. A new KTT 350-cc model was produced for the private owner. It was called the MK VIII “big valve,” and it utilized a 1.156-in. GP carburetor and alloy wheel rims. The new KTT was a very popular mount, and its 1 15-mph top end was considered to be an exceptional performance.

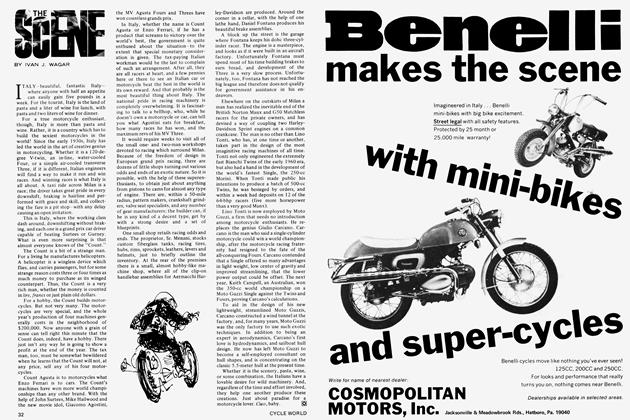

One of the most interesting bikes that year was the 250-cc Benelli—an Italian marque with a reputation for building fast bikes. The thumper had a bore and stroke of 65 by 75 mm, and the power output was 27 bhp at 8500 rpm. With a speed of 1 12 mph, the dohc Single was a strong threat to Guzzi supremacy.

When the flag fell to start the 1950 Lightweight TT, the Moto Guzzi team darted into the lead. Dario Ambrosinion the lone Benelli was in 5th place, some 66 sec. behind by the end of Lap 2. Then the Italian began his drive and the fourth lap saw only 37 sec. difference, the fifth 28 sec. and the sixth showed only 15. On the last lap Dario broke the lap record and pipped Maurice Cann at the finish line to win by only 0.2 sec.

After such a thrilling 250 event, the fans eagerly anticipated the Junior TT to see if the new Nortons could upset the Velocette. Bob Foster was the main Velo rider, and a promising newcomer named Geoff Duke had joined the Norton team. In the race itself Foster became the first to break Stanley Woods’ 1938 lap record of 85.30 when he clocked 86.22 on his second lap. Foster’s luck was out, though, for he retired with a broken rear brake rod at Quarter Bridge. The Velocette’s retirement took most of the luster out of the race, since the AJS Singlesjust didn’t have the speed to hold the new Nortons. The Velocette, incidentally, had a huge 9-gal. fuel tank in an attempt to run the race without a pit stop. But the handling left something to be desired, so for later races the standard 5-gal. tank was used. With the speedy Velocette out, Artie Bell led the Featherbed Nortons home to a smashing 1-2-3 finish.

The Senior TT also was a Norton walkover, with Geoff Duke heading another 1-2-3 finish over the AJS Twins, Velocettes, and Moto Guzzis. The handling and roadability of these Nortons was exceptional, and for 1951 the marque adopted the featherbed frame on the production Manx model.

The year 1951 proved to be more of a refinement year than one of any radical new designs. All the marques had new bikes, and the logical course of action was to develop these designs. The Norton, Velocette, AJS, Guzzi, and Benelli were the main contenders that year, and each marque succeeded in extracting just a little more power and a little better roadability than the previous year.

Velocette did spring somewhat of a surprise, however, when they announced they were dropping their venerable old 500 and replacing it with a new 250 model. The little thumper had engine measurements of 68 by 68.5 mm, and a dohc head was used. The frame was a new design with two horizontal top tank rails, and a large 8-in. twin-leading-shoe front brake was used. A five-speed gearbox was another interesting feature. This effort by the Hall Green concern was significant in that it was the first serious British attempt to defeat the Italians in the 250-cc class since the early 1930s.

The 1951 TT races were run off true to form-just as the “experts” predicted. Geoff Duke really came into his own, winning both the Junior and Senior TTs at the record speeds of 89.9 and 93.83 mph. In the Junior TT, Geoff lapped at 91.38 mph, and the Senior event saw the lap record rise to 95.22 mph. Behind Duke in the Senior TT was an AJS Porcupine and then four more Nortons; and in the 350-cc event he was followed by two Nortons, an AJS Single, and then two Velocettes. This was one of Norton’s finest hours as well as being the climax of the classical racing Single.

In the Lightweight TT, there once again was a terrific fight between the Benelli and Guzzi teams, but this time Tommy Wood edged out Ambrosini by just a few seconds. The little thumpers were really moving that day, and Wood’s record average was no less than 81.39 mph.

Another Italian walkover was the new Ultra-Lightweight TT-an event for 125-cc machines. The dohc Mondials completely dominated this race, and their 10,000-rpm performance shook many a hardened TT fan. Cromie McCandless was the victor, and he averaged no less than 74.85 mph.

During the long winter, race shops all over the continent were busy. Europe had recovered from the war and the sales of motorcycles had rapidly expanded. Many companies poured money into their racing programs, and some highly sophisticated designs emerged from the race shops.

In England, Norton continued to be the leader, and in an effort to gain more engine speed and power the works bikes had their bore and stroke changed to 75.9 by 77 mm on the 350 and 85.93 by 86 mm on the 500 model. Much larger valves and carburetors were fitted, and the extensive use of aluminum alloy brought the dry weight down to around 300 lb. These new engines revved much faster than the old long-stroking powerplants,

and the bikes were considerably faster. The big 30-incher, for instance, was spinning to 7200 rpm compared to the previous engine’s 6700, and top speed was about 130 mph, compared to 125.

The illustrious AJS Porcupine also underwent a great deal of development. The engine was raised from its horizontal mounting to a 45 degree position, and the finning was orthodox instead of being spiked. A new “open” frame was used with a 6.5-gal. fuel tank, and the oil was contained in a crankcase sump in an effort to lower the center of gravity. The Twin was reputed to be very fast, but its handling on the twisty Isle of Man circuit was not in the class of the Norton.

AJS also had another new bike-this one a 350-cc triple-cam Single. The engine featured a chain drive to the cams. Two exhaust valves and exhaust pipes were used. The bore and stroke of this engine was changed to 75.5 by 78 mm, and the thumper also was known as a very speedy machine.

The real development of the racing motorcycle was to be in Italy. This was the beginning of a great Italian chapter in the story of the TT, and a new concept of high revs and many gears eventually was to prove supreme.

The machine that had the TT fans talking in 1952 was the MV Agusta—a four-cyUnder beast that had, along with the Güera Four, proven to be much faster than the British Singles. The MV had a dohc head, four carburetors and exhaust pipes, a telescopic front fork, swinging arm frame, and chain drive. The power output was 55 bhp at 10,000 rpm, and maximum speed was 135. But the handhng of the MV was nowhere near that of the Norton, and the Isle of Man is a very twisty circuit.

Another potent ItaUan mount was the Guzzi V-twin, which by then was producing 48 bhp at 8000 rpm. Maximum speed was Usted at 129 mph, but the Twin was stül plagued with unreliabiUty. Other notable Latin machines were the high-revving F.B. Mondial and MV Agusta 125s. These Uttle screamers were claimed to have a maximum speed of around 100 mph, which was a remarkable performance from such tiny engines.

The 1952 TT series started with the 125-cc event. It was won by Cecü Sandford on his MV Agusta over the

favored Mondials. In the Lightweight TT it was all Moto Guzzi, with Fergus Anderson winning at the remarkable average of 83.82 mph. The Uttle Velocette in the hands of Les Graham finished 4th at a creditable 82.06 average.

The Junior TT was once again a Norton benefit with Geoff Duke and Reg Armstrong leading four works AJS Singles. Duke set up a record 90.29-mph average and looked unbeatable.

The Senior TT saw Duke lead through Lap 4 until his clutch failed. Les Graham then assumed the lead on his MV Four with Reg Armstrong only 12 sec. behind. Graham, however, appeared to be slowing while the Irishman was gaining, so the race was a real thriller. In the end it was Armstrong by only 26.6 sec., and as he crossed the finish line the Norton’s primary chain snapped and slithered across the road.

Lady luck had once again played to Norton’s advantage. A post-race examination explained why Graham had slowed during the latter half of the race. An over-liberal oü supply to the rear chain had flung oü on the gearshift lever, Graham’s toe slipped off the shift lever and the gearbox went into neutral. The resultant over-revving caused the exhaust valves to touch the pistons, and the MV lost about 400 revs and several horsepower.

So the first six years of postwar racing dramatically drew to a close. Speeds in the Senior TT had risen from 82.81 to 92.97 mph. The Isle of Man, more than ever, was considered to be the supreme challenge for both man and machine, and its hundreds of corners, uphill climbs, downhül stretches, and jumps put a stress on machines that no other course could equal. Europe was fully recovered from the war and motorcycle racing once again was big business.

One of the hallmarks of this era was the 1947 and 1948 successes of the private owners. With the factories racing on a limited budget, many of the TT races had works bikes in 1st or 2nd place only.

By 1952, the scene had changed, as works riders filled the first six places. The speed difference between the exotic works bikes and the production models was also increasing a sure sign of intense technical development in the racing shops.

Probably the most significant item in this era was the passing of the Velocette. It was the policy at Hall Green to race a machine nearly identical to that produced for the private owner; when it became obvious that this type of machine could no longer win, they quit racing. Thus, a great legacy dating from 1925 passed from the scene.

In the next era it would take great capital to compete successfully in the Isle of Man. Many new and complex machines would debut, and speeds would rise well beyond the magical 100-mph average.

The Contemporary Scene-1953 to 1967The Days of Many Cylinders and Horrendous Revs

SEVEN YEARS after World War II ended, the economy of Europe was flexing its muscles. Europe had slowly rebuilt itself after the devastation of the war, and motorcycle production had greatly expanded. With worldwide marketing of their motorbikes, many manufacturers turned to the great classical grand prix races in an attempt to gain advertising prestige.

Firmly entrenched at the summit of international racing was the Isle of Man TT—the most challenging race course in the world. With its 37.75 miles of winding road, uphill stretches, downhill runs, and hairpin corners, it was a test of man and machine without equal.

In 1952, the British Singles still were considered unbeatable, but, in 1953, the foreign challenge became intense. The most talked about machine that year was the fabulous Gilera Four—an Italian masterpiece that had a much greater turn of speed than the British Singles. The Gilera team was formidable, as Geoff Duke and Reg Armstrong had left the Norton camp to straddle the howling Fours.

In the 350-cc class, the Moto Guzzi Single represented the foreign challenge. The new Guzzi was the well proven 250-cc model bored out to 320 cc. It had the traditional, horizontally mounted ohc engine with an outside flywheel. Another notable innovation was the experimental use of sheet metal molded around the steering head to improve air penetration. This first use of the fairing principle was historic, and time was to prove its value.

In the 250-cc class, the British were hopelessly outclassed. The Guzzi thumper was invincible with its 27-bhp, ohc engine, five-speed gearbox, and 109-mph top speed. A new challenger from Germany made its debut-the NSU Twin-a dohc bomb that featured a six-speed gearbox. The NSU was known to be very fast, though the roadability was not nearly so good as the Guzzi.

Another interesting German racer was the 350-cc DKW Three—a two-stroke that weighed only 180 lb. The DKW engine was very unusual, with its two cylinders in an upright position and one cylinder in a horizontal position to the front of the crankshaft. The two-stroke “Deek” featured the now commonly accepted “loop scavenging” principle, where the transfer ports are inclined upwards. It was historic in that it was the first competitive two-cycle design in the postwar era. The Three was known for its terrific acceleration, but lack of reliability plagued the model.

In the 125-cc class, the single-cylinder dohc MV Agusta and Mondial were considered unbeatable, but the new NSU Single was reputed to be a worthy challenger. It was obvious that many designs from many countries were out to win the coveted TT.

When the flag dropped to start the 1953 races, it was the ultra-lightweights away, with Les Graham (MV) leading home Werner Haas (NSU). Italian supremacy also was manifest in the Lightweight TT when Fergus Anderson brought his Guzzi home ahead of Haas on the NSU Twin. In the Junior TT, the British showed the world that the Norton was still a great racing bike. Ray Amm and Ken Kavanagh trounced Anderson on his Guzzi. The Senior event saw Geoff Duke way out in front on his screaming Gilera, with Amm over a minute astern. Geoff then crashed, and Ray came home the winner ahead of Jack Brett (Norton) and Reg Armstrong on the other Gilera. With the AJS Porcupine Twins in 4th and 5th, it was a great victory for good handling over sheer power.

By spring of 1954, it was obvious that the race shops had been busy during the winter. Realizing that the foreigners would soon find reliability and good handling to match their horsepower, the British brought out radically new designs. Norton had new powerplants for the works bikes, with bore and stroke measurements of 90 by 78.4 mm and 78 by 73 mm on the two models. An outside flywheel was used, as was a five-speed gearbox. The British marque also began experiments with streamlined fairings to gain speed.

The AJS also was considerably redesigned, with a new engine that developed 54 bhp at 7500 rpm. The 335-lb. Twin had an unusual 6.5-gal. fuel tank that had low side sections in an effort to lower the center of gravity, but the handling still was not the best. The power was a little better than the Singles, but still well below the 60-65 bhp claimed by Gilera.

Across the channel in Germany, the Herringfolk had really improved their raceware. The NSU Twin, for instance, was developing the remarkable output of 42 bhp, and the performance through its six-speed gearbox was shattering. Top speed was listed as 123 mph, with an aluminum alloy “dolphin” fairing, and the handling had been greatly improved. The 125-cc Single had undergone the same treatment, and 20 bhp was claimed.

The Italians also had improved their TT bikes. Gilera sported a modest “head fairing” around the steering head, but Guzzi had a full “dustbin” shell that completely covered the front two-thirds of the bike. This use of streamlining on the Guzzi allowed, a speed of over 130 mph on only 33.5 bhp-a great testimony to the advantage of the fairing.

The races themselves were full of drama. In the 125-cc event, Rupert Hollaus (NSU) edged out MV ace Carlo Ubbiali. This was considered quite an upset. The Lightweight TT saw a tremendous show by Werner Haas on his 250-cc NSU, with the race record going to 90.88 mph. This was over 5 mph faster than the previous lap record, so the German Twins truly had overwhelmed the old Guzzi Singles.

The Junior TT saw the new 350-cc Guzzis lead early, only to drop out. New Zealander Rod Coleman brought the triple-cam AJS Single home first. The Senior TT was run in a torrential downpour, and Ray Amm once again pulled off the victory over Geoff Duke. This later race proved that a good Single on a wet road is more manageable than the powerful Four.

A sidecar race also was included that year, for the first time since 1925, and Eric Oliver scored the victory with his Norton. Eric was followed by three BMW Twins—a hint of things to come.

During the long winter, several momentous decisions were made that would alter the history of the TT. The first was the announcement from Norton and AJS that they were dropping active participation in world championship racing. The reason given was that successful participation took an exotic machine far removed from standard production model practice, and few advantages could thus be passed on to their customers. The second announcement was from the NSU factory. The firm planned to mount a works rider on a standard production “Sportmax” racer and drop the speedy works models.

So the 1955 TT series became an Italian benefit, with Geoff Duke leading the pack with his Senior TT win. Geoff averaged a sizzling 97.93 mph and came within a whisker of the magical century lap with his 99.97 record. The Junior TT saw the Guzzis at last acquire reliability. Bill Lomas was the victor at 92.33 mph.

The two Lightweight events were Carlo Ubbiali triumphs. On his MV Agustas he averaged 71.37 and 69.67 mph, respectively, on the slow “Clypse” circuit. The sidecar race saw the first of many BMW wins, with Walter Schneider the driver.

Foreign factories expended even more intensive effort the next year. Gilera was not represented because of the early season injury of several riders, but the four-cylinder MV took its place. The MV had a young fellow by the name of John Surtees in the saddle, and the 1956 TT was the start of a great Surtees legend.

In the 125-cc event, Carlo Ubbiali had little trouble disposing of the two-stroke Montesa team. In the 250-cc race, he easily trounced the NSU, CZ, and Guzzi riders into submission. The Junior TT saw a strong Surtees challenge, with Ken Kavanagh coming up fast on his Guzzi. Kavanagh won the race after Surtees dropped out on the last lap, with the Guzzi rider turning in his fastest lap on the final circuit. Surtees simply had no opposition in the Senior TT, and he chalked up his first of many victories. The sidecar event again went to BMW, this time with Fritz Hillebrand on board.

In 1957, to commemorate the 50th year of the classic (1907 to 1957), the organizers entitled it the Golden Jubilee TT. The Senior event was scheduled for eight laps, instead of seven. Factories all over Europe responded for this great event. Several new names joined the competition.

Racing fever ran high that June, as the Italians went all out for victory. The MV E'our was becoming a truly roadworthy mount, and Gilera was getting 50 and 70 bhp from the 350and 500-cc models. Guzzi had fabulously light 350 and 500 Singles, as well as a 75-bhp V-8. Mondial’s seven-speed 125 would do 125 mph; the 250-cc thumper was good for 140. The Mondials even had tail fairings to go with their full dustbin streamlining.

In the sidecar race, Fritz Hillebrand headed a 1-2-3 BMW victory with the Nortons well astern. The two Lightweight events had tremendous battles, with Mondial riders Tarquinio Provini and Cecil Sandford winning the 125-and 250-cc races over the MV Agusta.

The Junior and Senior TTs were magnificent races. Bob MacIntyre set a record lap of 101.12 mph-the first time the Island had been lapped at over the “ton.” Bob was followed home by an MV, a Gilera, and two Guzzis in the Senior TT; and two Guzzis and an MV in the Junior race. The Italian marques truly had their greatest hour that day.

After this great year with such exotic machines, race followers were disheartened at two announcements made during the winter. The first was that Gilera, Guzzi, and Mondial were retiring from the racing game. Costs had soared when the factories raced with such fervor and developed their fabulous grand prix contenders. A declining sales rate simply didn’t supply the needed profits to sustain the campaign.

The other announcement, from the governing Federation Internationale Motocycliste, limited streamlining to the now-common dolphin type. Speeds with the full dustbin fairings had been fantastic during 1957, with the V-8 Guzzi clocked at 178 mph on the Masta Straight in the Belgian Grand Prix. The FIM thought it best to drop the speeds a wee bit, and this regulation is still in force today.

The array of exotic machines was gone from the 1958 TT races. John Surtees rode MV Agusta Fours in the Junior and Senior events. The production British Singles were hopelessly outclassed. The MV “fire engine” was a great bike, and Surtees’ riding was masterful. The Four featured double overhead cams, a fivespeed gearbox, and an orthodox suspension system. Power output at the rear wheel was claimed to be 43 bhp at 10,200 rpm on the 350, and 56 at 9800 rpm on the 500-cc model. The MV was not quite as fast as the Gilera, but the acceleration was claimed to be superior.

In the 250-cc class, the MV had only modest opposition from privateers on production NSU “Sportmax” models and the CZ four-stroke Single. In the 125-cc event, there was some spirited competition from the Italian Ducati and the East German MZ.

The Ducati was a Single with a desmodromic head. This “desmo” engine had cams to both open and close the valves, and valve float was therefore impossible. The Ducatis were fast, and they were worthy challengers to the MV Agusta.

The MZ was an interesting machine with its rotary valve two-stroke engine, developed by Walter Kaaden. The power output was exceptional, but reliability was a problem. The MZ, however, did achieve agreat record. It is the true father of the current two-cycle racing engine.

John Surtees easily won the 1958 Junior and Senior TTs; his teammate, Provini, won the Lightweight event. Carlo Ubbiali worked hard to defeat the gang of Ducatis and MZs in the UltraLightweight TT, though, and for the next few years this would be the case for the smaller MVs. The sidecar race continued to be a BMW benefit, with Walter Schneider once again the winner.

The 1959 TT races had much the same results as the previous year. Surtees again captured the two larger classes and Provini won the two lightweight races. The 125-cc MZ two-strokes were very fast, but lack of reliability still plagued them. The BMW continued to dominate the sidecar race with Walter Schneider again the winner.

Most noteworthy of the 1959 races was the entrance of a Japanese make in the Ultra-Lightweight TT. Honda was its name, and its team of dohc 125-cc Twins spun to 14,000 rpm. The front fork was a cumbersome appearing leading-link design, and handling was reputed to be terrible. The Honda also was lacking in horsepower; 6th, 7th, 8th, and 11th places were the best obtained.

History, however, was to record that this Oriental invasion had great significance. The Japanese people were entering the era in their industrial revolution when people quit walking and began buying motorbikes. The resultant large sales volume produced healthy profits, and, with such a large market, the prestige of race winning became very important. It is interesting to note that Japan’s “motorcycle era” arrived at a time when the European economy had so well recovered from the war that people were parking their bikes and purchasing automobiles. European motorcycle sales were naturally on the decline, and all the factories were losing interest in racing.

It surprised no one that Surtees and teammate John Hartle won the Senior and Junior TTs in 1960. Neither did it surprise anyone that Ubbiali and Gary Hocking took the 125and 250-cc races, or that Helmut Fath won the sidecar race. What was surprising was the strong showing of the Honda, as the marque took a 6th in the 125 event and 4th, 5th, and 6th in the 250-cc class.

The new Hondas were vastly improved over the previous year. The 125-cc Twin and 250-cc four-cylinder engines featured four valves per cylinder, and they were canted forward slightly in the frames for better cooling. A standard telescopic front fork was used, and the horsepower was notably greater.

The following year was full of surprises. The first was the retirement from bike racing of John Surtees. The second was the mechanical failures of Gary Hocking’s MVs in the Senior and Junior TTs. These retirements allowed Mike Hailwood and Phil Read to win on their Nortons—the first British wins since 1954.

The next surprise was the complete domination by Honda in the 125 and 250 races. The Nipponese bikes had been modified during the winter, and the two powerplants were churning out something like 25 bhp at 13,000 rpm and 45 bhp at 14,000 rpm, respectively. Both models featured six-speed gearboxes, and maximum speeds were listed as 112 and 137 mph.

In the 250 TT, the great Bob MacIntyre set a fantastic 99.58-mph lap record from a standing start, but Mike Hailwood won when Bob’s engine failed. Mike also won the 125-cc event, and Hondas took the first five places in each class. Other interesting notes were the 6th place of a 250 Yamaha two-stroke and yet another BMW sidecar win by Max Deubel.

The following year saw the MV factory return with the formidable team of Gary Hocking and Mike Hailwood. These two fellows easily won the Senior and Junior TTs. The only other machine of any real interest was the Jawa Twin of Franta Stastny that came home 3rd behind Hailwood and Hocking in the Junior TT. The Czech-built Twin featured a dohc engine, but the speed was not quite up to the speedy Fours.

The two Lightweight events were Honda walkovers, with Derek Minier heading a 1-2-3 finish in the 250-cc class. Derek’s average speed was 96.68 mph, and the Guzzi, Aermacchi, and Bultaco teams were left far behind. Luigi Taveri won the 125-cc class at an 89.88-mph average, and other Honda riders filled the next four places.

The only real surprise that year was Chris Vincent’s sidecar win with his BSA-powered rig. One by one, the faster BMWs dropped by the wayside, and Chris finally came home the winner. The BSA powerplant was a pushrod Twin that the factory had produced especially for the race.

The 1962 TT series also featured an event to cater to the newly established 50-cc class. The winner of this inaugural event was Ernst Degner on a Suzuki, which was considered to be somewhat of an upset over the favored Hondas and Kreidlers. The win was also historically significant as it was the first victory by a two-stroke engine since Ewald Kluge’s 1938 win on a blown DKW. The Suzuki was a Single, and it had a rotary disc inlet valve—a design that was to feature prominently in future TT races.

When the 1963 classic rolled around, there were many new machines on the starting grid. Geoff Duke obtained the loan of some Güeras from the famous Arcore factory, and riders John Hartle and Phil Read chased Hailwood to the finish in the Senior TT. The Junior TT also had the old Güeras competing, but this time the new 350-cc Honda Four of Jim Redman showed them the way home.

The 250-cc Honda Four once again romped home the winner in the Lightweight TT, but a surprisingly strong showing was made by Furnio Ito on a Yamaha Twin. The Yamaha was a twostroke with rotary disc inlet valves, and it finished within seconds of the Honda.

The 50 and 125 events were captured by Suzuki riders Mitsuo Itoh and Hugh Anderson, and these two-stroke speedsters also featured rotary disc inlet valves. The 50-cc model was a Single and the 125-cc was a Twin; both were air cooled.

In the sidecar class, the BMW riders got revenge for their humiliating defeat of the previous year. Florian Camathias headed a line of five of the Munich Twins, and the speed was up to 88.38 mph.

During the winter, the Honda engineers designed new engines in an effort to hold the speedy two-strokes. The 125-cc Twin was dropped, and a new Four that turned to 18,000 rpm made its debut. The 50-cc Twin that had been developed the previous year was retained, as were the 250 and 350 Fours.

The Senior TT once again was a walkover for Hailwood and his scarlet red MV. Jim Redman had no competition in the 350 class. The Lightweight TT also was a Honda victory, with Redman winning at 97.45 mph. In the 125-cc race, Honda’s new “Four” made its debut, and what a debut it was! Luigi Taveri averaged a fantastic 92.14 mph with a lap at 93.53 to show the world what a fabulous racer this was.

In .the 50-cc class, the two-stroke retained its edge. Hugh Anderson subdued the fierce Honda challenge. And in the sidecar class, Max Deubel scored yet another BMW win to prove that the flat opposed Twin still was the best powerplant for the three-wheeled brigade.

The 1965 TT was a truly historical series, with speed displayed as never before. During the 1964 season, Phil Read had badly trounced the Honda with his 250-cc Yamaha Twin, so Honda brought out a new Six in an effort to gain more speed. The Honda factory also retired their 125-cc Four and brought out a new “Five,” which was certainly a most unusual number of cylinders for a motorbike. Yamaha responded with a new bike also—a 125-cc Twin that was exceptionally fast.

In Italy, the famous MV Agusta marque was excitedly developing a new machine for Mike Hailwood and newcomer Giacomo Agostini. The new MV was a 350-cc Three, much lighter and trimmer than the older four-cylinder model. The MV also used four valves per cylinder—a practice well proven by the Honda.

The 1965 Senior TT was a pushover for Hailwood against the old production British Singles, and the race was slowed by a driving rain. The Junior event was a real donnybrook, with Hailwood setting a 102.85-mph lap record from a standing start. Then Mike retired to let Redman and Phil Read (254-cc Yamaha) battle it out. Redman won at the record speed of 100.72 mph, and Agostini came home a game 3rd.

The sidecar race was once again a BMW benefit with Max Deubel the victor, but' the two Lightweight events were full of surprises. The first was the Honda win in the 50-cc class by Taveri, and the second was the 125-cc Yamaha win by Phil Read at a scorching 94.28-mph average.

The final year in this story of the great TT was 1966, and a seaman’s strike very nearly halted the whole show. Arrangements were made to hold the races in late August and early September, and race records were established in all but the Senior race, where it rained a wee bit.

Probably the most significant item that year was Mike Hailwood’s switch from the MV camp to the mighty Honda stable. Another interesting matter was the new 500-cc Honda Four that was reputed to develop 80 beastly horsepower. Not to be outdone, MV produced a new 500-cc Three for Agostini that was considerably lighter than the bulky Honda.

Hailwood never looked greater than he did in the Senior TT. The lap record was pushed up to 107.07, and Agostini was convincingly pushed into 2nd place. In the Junior TT, the Italian got it back with a race record of 100.87 and a lap record of 103.09 mph.

What was really shattering was the speeds attained in the two Lightweight events. Hailwood, even though he had no serious competition, racked up a fantastic 101.79 average in the 250 event with a lap record at 104.29 mph. In the 125-cc event, Bill Ivy smashed the lap and race records to the tune of 97.66 and 98.55 mph on his Yamaha Twin.

The little 50-cc Honda with Ralph Bryans aboard scored another win at 85.66 mph, and Fritz Scheidegger won the Sidecar TT on his BMW. The result of the sidecar event was actually not known for several months after the race, however, as Fritz had been disqualified on a minor technical point. A hearing later reinstated him as the winner, and he went on to be crowned champion of the world.

During this contemporary era there were several significant engineering advances for which the period will be noted. Perhaps the most important was the return of the two-stroke engine as a raceworthy design. Next in line would be the complete domination of multi-cylinder designs over the classic ohc racing Single. Last, there was the adoption of some form of streamlining on the bikes. From a modest “head” fairing in 1953, the shape soon became the “dolphin.” Next it was full “dustbins” by 19.55, and then, for 1958, the FIM outlawed all but the dolphin type. Indicative of all this progress is the increase in speeds from 1953 to 1966 in the 250-cc class-from 84.73 to 101.79 mph.

So ends this story of the TT—the world’s greatest motorcycle race. From a humble beginning in 1907 on rough dirt and cobblestone roads, it has become the greatest classic in the world. The uniqueness of the course, the magnificent setting, and the glorious and colorful history—it is truly the greatest legend in all of motorcycledom. For the sake of our sport, long may it live!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

Round UpRound Up

May 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

The Service DepartmentThe Service Department

May 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1969 -

The Scene

The SceneThe Scene

May 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Travel

TravelSpecial Report: the Moving Forces Behind Motorcycle Legislation

May 1969 By J. Bradley Flippin -

Travel

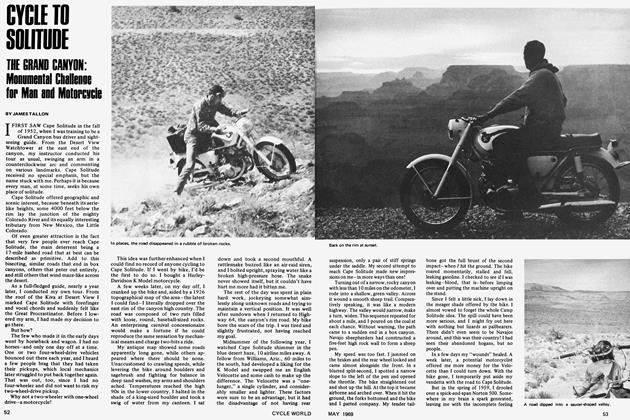

TravelCycle To Solitude

May 1969 By James Tallon