CYCLE TO SOLITUDE

THE GRAND CANYON: Monumental Challenge for Man and Motorcycle

JAMES TALLON

I FIRST SAW Cape Solitude in the fall of 1952, when I was training to be a Grand Canyon bus driver and sightseeing guide. From the Desert View Watchtower at the east end of the canyon, my instructor conducted his tour as usual, swinging an arm in a counterclockwise arc and commenting on various landmarks. Cape Solitude received no special emphasis, but the name stuck with me. Perhaps it is because every man, at some time, seeks his own place of solitude.

Cape Solitude offered geographic and scenic interest, because beneath its aerielike heights, some 4000 feet below the rim lay the junction of the mighty Colorado River and its equally interesting tributary from New Mexico, the Little Colorado.

Of even greater attraction is the fact that very few people ever reach Cape Solitude, the main deterrent being a 17-mile hashed road that at best can be described as primitive. Add to this bisecting, similar roads that end in box canyons, others that peter out entirely, and still others that wind maze-like across the desert.

As a full-fledged guide, nearly a year later, I conducted my own tour. From the roof of the Kiva at Desert View I marked Cape Solitude with forefinger and vocal chords and suddenly felt like the Great Procrastinator. Before I lowered my arm, I had made my decision to go there.

But how?

The few who made it in the early days went by horseback and wagon. I had no horses—and only one day off at a time. One or two four-wheel-drive vehicles bounced out there each year, and I heard a few people brag that they had taken their pickups, which local mechanics later struggled to put back together again. That was out, too, since I had no four-wheeler and did not want to risk my two-wheel-drive pickup.

Why not a two-wheeler with one-wheel drive—a motorcycle!

This idea was further enhanced when I could find no record of anyone cycling to Cape Solitude. If I went by bike, I’d be the first to do so. I bought a HarleyDavidson K Model motorcycle.

A few weeks later, on my day off, I cranked up the bike and, aided by a 1926 topographical map of the area—the latest I could find—I literally dropped over the east rim of the canyon high country. The road was composed of two ruts filled with loose, round, baseball-sized rocks. An enterprising carnival concessionaire would make a fortune if he could reproduce the same sensation by mechanical means and charge two-bits a ride.

My antique map showed some roads apparently long gone, while others appeared where there should be none. Unaccustomed to crawling speeds, while levering the bike around boulders and sagebrush and fighting for balance in deep sand washes, my arms and shoulders ached. Temperatures reached the high 90s in the lower country. I halted in the shade of a king-sized boulder and took a swig of water from my canteen. I sat down and took a second mouthful. A rattlesnake buzzed like an air-raid siren, and I bolted upright, spraying water like a broken high-pressure hose. The snake never showed itself, but it couldn’t have hurt me more had it bitten me.

The rest of the day was spent in plain hard work, jockeying somewhat aimlessly along unknown roads and trying to maintain a vertical position. It was well after sundown when I returned to Highway 64, the canyon’s rim road. My bike bore the scars of the trip. I was tired and slightly frustrated, not having reached my goal.

Midsummer of the following year, I watched Cape Solitude shimmer in the blue desert haze, 10 airline miles away. A fellow from Williams, Ariz., 60 miles to the south, had developed a liking for the K Model and swapped me an English Velocette and some cash to make up the difference. The Velocette was a “onelunger,” a single cylinder, and considerably smaller and lighter. These factors were sure to be an advantage, but it had the disadvantage of not having rear suspension, only a pair of stiff springs under the saddle. My second attempt to reach Cape Solitude made new impressions on me-in more ways than one!

Turning out of a narrow, rocky canyon with less than 10 miles on the odometer, I rode into a shallow, green valley. Across it wound a smooth sheep trail. Comparatively speaking, it was like a modern highway. The valley would narrow, make a turn, widen. This sequence repeated for about a mile, and I poured on the coal at each chance. Without warning, the path came to a sudden end in a box canyon. Navajo sheepherders had constructed a five-feet high rock wall to form a sheep pen.

My speed was too fast. I jammed on the brakes and the rear wheel locked and came almost alongside the front. In a blurred split-second, I spotted a narrow slope to the left of the pen and opened the throttle. The bike straightened out and shot up the hill. At the top it became airborne and arched over. When it hit the ground, the forks bottomed and the bike and I parted company. My tender tailbone got the full brunt of the second impact-when I hit the ground. The bike roared momentarily, stalled and fell, leaking gasoline. I checked to see if I was leaking—blood, that is—before limping over and putting the machine upright on the stand.

Since I felt a little sick, I lay down in the meager shade offered by the bike. I almost vowed to forget the whole Camp Solitude idea. The spill could have been more serious, and I might fry out here with nothing but lizards as pallbearers. There didn’t even seem to be Navajos around, and this was their country! I had seen their abandoned hogans, but no people.

In a few days my “wounds” healed. A week later, a potential motorcyclist offered me more money for the Velocette than I could turn down. With the bike gone, I temporarily put aside my vendetta with the road to Cape Solitude.

But in the spring of 1959, I drooled over a spick-and-span Norton 500. Somewhere in my brain a spark generated, leaving me with the incomplete feeling that I had left a project unfinished. I bought the bike.

The Norton treated me kindest of all.

My mental outlook was heightened on the third try for Solitude, because I had found a jeep owner who said he had been to the Cape. He provided solid directions. Unfortunately, some of the markers he mentioned were no longer in existence. Again, I wandered in rolling hills, canyon mazes and sandy washes, covering former ground. The sun beat down, and this time the temperature was well over 100 degrees.

The Norton was boiling hot beneath me. No wonder. I was fighting my way up and down steep, rocky hills at a snail’s pace, and the cooling fins received little moving air. My water was getting low, and frustration began to gnaw at me. Then I topped a high rise and got a broad view of the country. A good road, better than any I’d seen in this country yet, dipped into a huge, saucer-shaped valley, passing a landmark I knew to be Gold Hill. Maybe I’ve hit it, I thought.

After crossing the basin, I rode onto a second rise and saw the dark slash of the Little Colorado River Gorge to the north. But the road dissolved into the sagebrush in another mile. Drawn by the canyon, I continued cross-country, standing on the pegs to ease my ride. With a certain sense of accomplishment, for the first time, I pulled to the lip of the canyon and gazed into its shadowy depths.

A welcome cool breeze came from below, and I took off my helmet and scratched a sweaty head. I was definitely at the wrong place, but I was willing to bet my half acre in Hades no other motorcyclist had been there. In fact, very few of Anglo-Saxon extraction had been here at all!

Below, on the gorge floor, powderblue water flowed to the west. One usually associates streams flowing through desert canyons as “too thick to drink and too thin to plow.” Because of this unusual color, I felt sure I was near Blue Springs. But westward, in the direction of Cape Solitude, the narrow canyon made a dozen turns and disappeared. I was still a long way from my mark.

I sat on a rock, enjoying my achievement and feeling as if I were the only person in the world. Suddenly, there was a snort behind me. Have you ever thought you were alone and unexpectedly found you were not? I nearly leaped into the gorge. Primitive reactions that prepare one instinctively for flight broke all records for getting me on my feet.

A picture-book Navajo man quietly sat astride a better-than-average-looking bay Indian horse. He wore the uncreased crown and flat-brimmed hat, typical of the older Indian men, and his hair was tied in a chonga, bunched in a roll and wrapped with white store string. His shirt was a flannel print and his pants were Levis. Instead of cowboy boots or moccasins, his shoes were of the flat, roundtoed work type.

He nodded at me. With this friendly gesture, I relaxed.

“How are you?” I asked.

“Good,” he replied, then added, “Where you come from?”

“Grand Canyon Village,” I said.

“That funny horse,” he grinned, pointing toward the motorcycle.

I’d been around Navajos long enough to know they are pretty sharp and have a good sense of humor. This certainly was not the first motorcycle he had seen. On his trips to the trading posts at Cameron, Tuba City or Flagstaff, he probably had watched dozens go by.

He dismounted and looked closely at the Norton, asking questions in slow, stilted English. I only hoped he enjoyed the meeting half as much as I did. The sun was getting low, and it was a long way back to Highway 64.

“Grass cheaper than gasoline,” the Indian said as we parted.

When I reached the highway this time, my spirits were much better. I was learning those back-country roads and becoming a more proficient rider.

The day of the Norton passed and, for a while, motorcycling became passe for me. However, it was hard not to notice the increasing number of new bikes and riders on the roads. The eye-catching lightweights merited full-page ads in most national magazine. My interest in bike riding renewed, and I bought a Honda Superhawk. A short time later, a buddy, Tommy Carr, got the bike bug—and a 250 Dream.

My dream of Cape Solitude was refired. On a coffee break, I bumped into Jim Blaisdell, biologist for the National Park Service, and found that Jim had just returned from Solitude. While I tried to hide my stupidity, he drew me a map showing the way.

Toward the end of summer, Tom knocked on my door one morning about an hour before daylight.

“What’s up?” I said, thinking some emergency was at hand.

“Let’s go to Cape Solitude,” he said.

I splashed water on my face, flung my gear and some grub into a backpack, and shortly after daybreak we were topping off the rim road. As we descended toward the desert, we cached a canteen of water and two one-gallon cans of gasoline for the return trip.

Tommy had been riding just a month, and the highway-intended Dream hit bottom often. He stood on the pegs like a veteran and muscled the bike through the rough stuff. My Superhawk was equipped with short touring bars-racing bars, some call them-and I soon found myself wishing for a few extra inches of leverage.

We traveled the same road I had during the past years. My eyes felt as if I were watching a ping-pong game, darting back and forth between where the front wheel was going and the left side of the road where the clinching marker, an iron rod driven into the ground, pointed the way to Cape Solitude.

Then there it was—big as life! I learned later that the rod was added by the National Park Service in 1959.

By this time, we had dropped over 1000 feet from the rim. The workout meted by the road and the warmer temperature put us in a healthy sweat. We stashed our backpacks and stored grub where we could. I made the sorry mistake of putting bananas in a camera box, where I thought they were safe from lens and shutter.

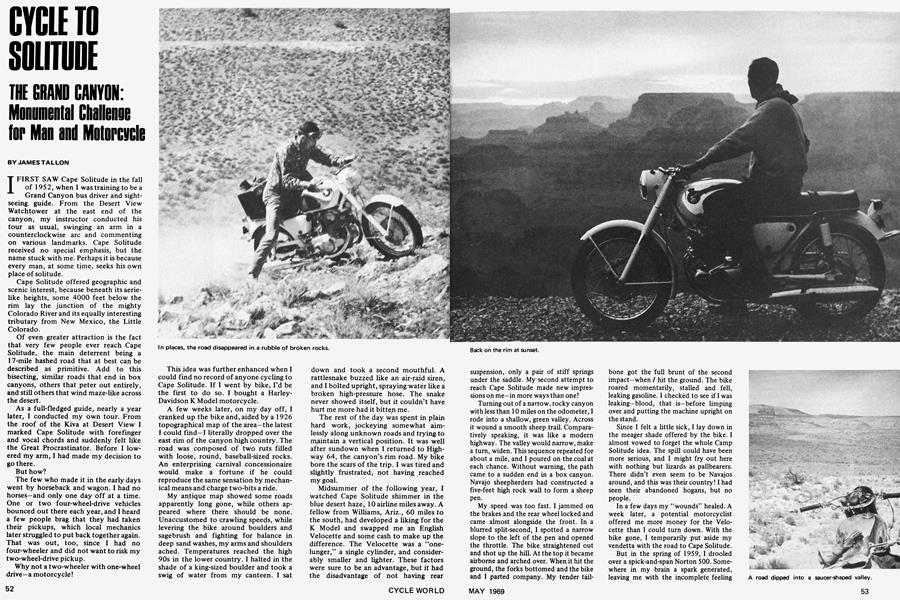

The roots of sagebrush and other plants had crawled into the road and made a washboard of it. New muscles announced themselves, and we stood on the pegs for miles. The distant land we had talked of from the Desert View Watchtower hopped and rolled beneath us. The low hills hid Cape Solitude from view, but I was sure we were on the right track. In places the road was just a steep, broken slope of loose rubble, and our highway-geared bikes spun out several times. Here the electric starters on the little Japanese bikes proved a boon. We could just latch onto the hand brakes, hold the bikes on the hill and push the little button that made it go again.

Some 20 miles northeast, near a mesa known as Shinumo Altar, a grumble emanated from building thunderheads. Some 180 degrees to the southwest, a similar condition existed. In between, not a breath of air moved.

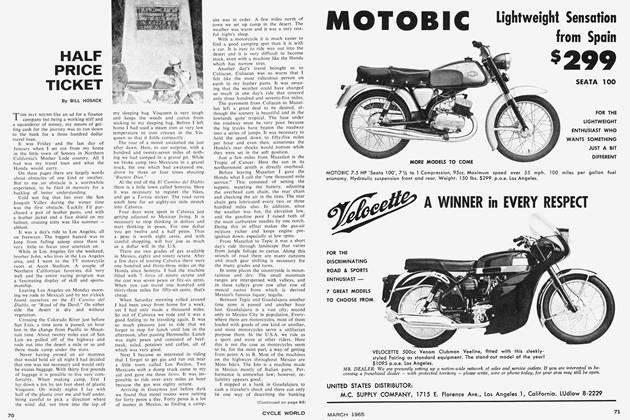

Cape Solitude came almost as an anticlimax. After all the grinding I had done trying to get there, I must have unconsciously expected a brass band to be on hand. But there was total silence once we shut down the motors. A wooden slat, sticking from a rock cairn guyed by wires, marked the spot. From the cairn we extracted a bottle. Inside, on a tattered piece of paper, were a half dozen names of others who had been here. We added ours, and our mode of transportation.

In a circling panorama we saw the broad expanse of Grand Canyon to the west, looked up Marble Canyon to the north and, to the east, the Little Colorado Gorge, the Painted Desert and the Navajo Indian country. Below sheer walls, measured in thousands of feet, the silt-rich Colorado River met the gleaming blue of the Little Colorado. It was almost too beautiful.

How do you aptly describe a place without paraphrasing description Man has written since he has been capable of recording? To me, Cape Solitude had seemed very special, or perhaps I should say extraordinary. Suddenly, the venture seemed much too easy.

We spent several hours exploring the general area at Cape Solitude. On the return trip to the highway, the building storm caught up with us in the juniper hills beneath the rim, and we weathered it in an abandoned, leaky Navajo hogan. Runoff from the storm turned part of the road into a shallow mudpack, but we reached the top without mishap.

On my previous trips into the Indian country, in search of Solitude, my odometer had averaged about 50 miles. At the end of our successful run, it registered just 34. It was the longest 34 miles I have ever traveled.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

Round UpRound Up

May 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

The Service DepartmentThe Service Department

May 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1969 -

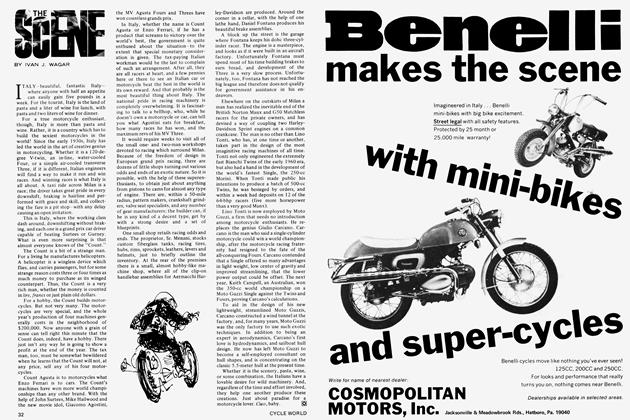

The Scene

The SceneThe Scene

May 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Travel

TravelSpecial Report: the Moving Forces Behind Motorcycle Legislation

May 1969 By J. Bradley Flippin -

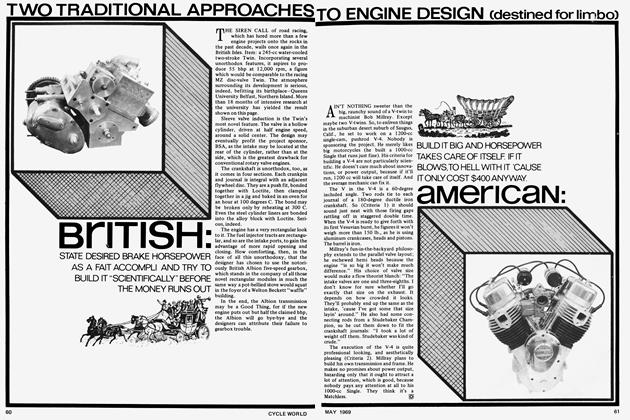

Development

DevelopmentTwo Traditional Approaches To Engine Design (destined For Limbo)

May 1969