TWO TRADITIONAL APPROACHES TO ENGINE DESIGN (destined for limbo)

BRITISH:

STATE DESIRED BRAKE HORSEPOWER AS A FAIT ACCOMPLI AND TRY TO BUILD IT "SCIENTIFICALLY" BEFORE THE MONEY RUNS OUT

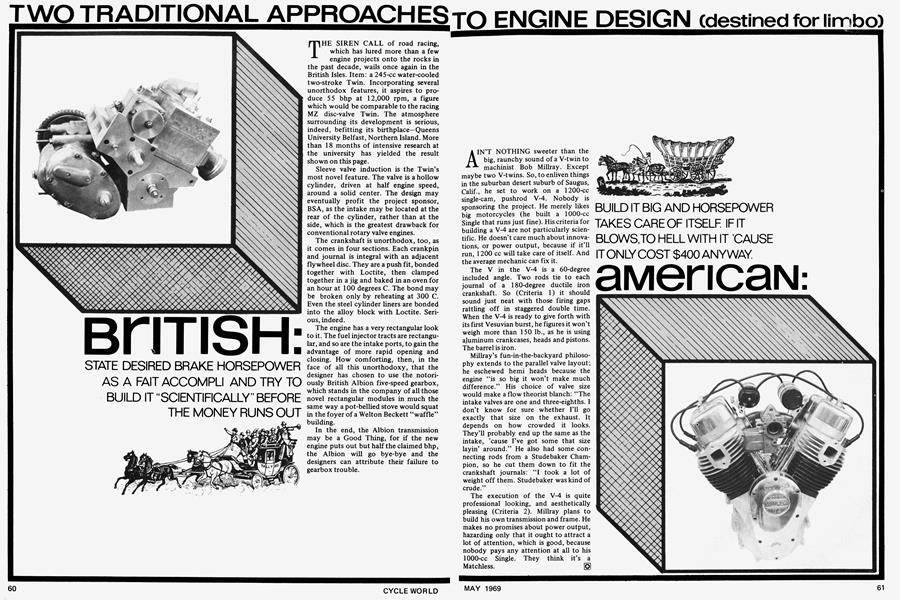

THE SIREN CALL of road racing, which has lured more than a few engine projects onto the rocks in the past decade, wails once again in the British Isles. Item: a 245-cc water-cooled two-stroke Twin. Incorporating several unorthodox features, it aspires to produce 55 bhp at 12,000 rpm, a figure which would be comparable to the racing MZ disc-valve Twin. The atmosphere surrounding its development is serious, indeed, befitting its birthplace-Queens University Belfast, Northern Island. More than 18 months of intensive research at the university has yielded the result shown on this page.

Sleeve valve induction is the Twin’s most novel feature. The valve is a hollow cylinder, driven at half engine speed, around a solid center. The design may eventually profit the project sponsor, BSA, as the intake may be located at the rear of the cylinder, rather than at the side, which is the greatest drawback for conventional rotary valve engines.

The crankshaft is unorthodox, too, as it comes in four sections. Each crankpin and journal is integral with an adjacent flywheel disc. They are a push fit, bonded together with Loctite, then clamped together in a jig and baked in an oven for an hour at 100 degrees C. The bond may be broken only by reheating at 300 C. Even the steel cylinder liners are bonded into the alloy block with Loctite. Serious, indeed.

The engine has a very rectangular look to it. The fuel injector tracts are rectangular, and so are the intake ports, to gain the advantage of more rapid opening and closing. How comforting, then, in the face of all this unorthodoxy, that the designer has chosen to use the notoriously British Albion five-speed gearbox, which stands in the company of all those novel rectangular modules in much the same way a pot-bellied stove would squat in the foyer of a Welton Beckett “waffle” building.

In the end, the Albion transmission may be a Good Thing, for if the new engine puts out but half the claimed bhp, the Albion will go bye-bye and the designers can attribute their failure to gearbox trouble.

AMERICAN:

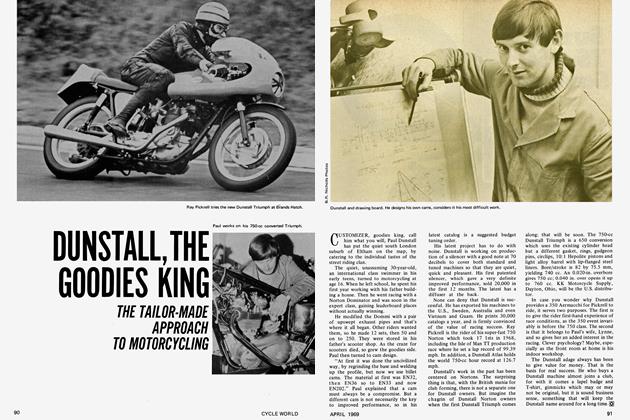

AIN'T NOTHING sweeter than the big, raunchy sound of a V-twin to machinist Bob Millray. Except maybe two V-twins. So, to enliven things in the suburban desert suburb of Saugus, Calif., he set to work on a 1200-cc single-cam, pushrod V-4. Nobody is sponsoring the project. He merely likes big motorcycles (he built a 1000-cc Single that runs just fine). His criteria for building a V-4 are not particularly scientific. He doesn’t care much about innovations, or power output, because if it’ll run, 1200 cc will take care of itself. And the average mechanic can fix it.

The V in the V-4 is a 60-degree included angle. Two rods tie to each journal of a 180-degree ductile iron crankshaft. So (Criteria 1) it should sound just neat with those firing gaps rattling off in staggered double time. When the V-4 is ready to give forth with its first Vesuvian burst, he figures it won’t weigh more than 150 lb., as he is using aluminum crankcases, heads and pistons. The barrel is iron.

Millray’s fun-in-the-backyard philosophy extends to the parallel valve layout; he eschewed hemi heads because the engine “is so big it won’t make much difference.” His choice of valve size would make a flow theorist blanch: “The intake valves are one and three-eighths. I don’t know for sure whether I’ll go exactly that size on the exhaust. It depends on how crowded it looks. They’ll probably end up the same as the intake, ’cause I’ve got some that size layin’ around.” He also had some connecting rods from a Studebaker Champion, so he cut them down to fit the crankshaft journals: “I took a lot of weight off them. Studebaker was kind of crude.”

The execution of the V-4 is quite professional looking, and aesthetically pleasing (Criteria 2). Millray plans to build his own transmission and frame. He makes no promises about power output, hazarding only that it ought to attract a lot of attention, which is good, because nobody pays any attention at all to his 1000-cc Single. They think it’s a Matchless.

BUILD IT BIG AND HORSEPOWER TAKES CARE OF ITSELF IF IT BLOWS,TO HELL WITH IT `CAUSE IT ONLY COST 4OO ANYWAY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

Round UpRound Up

May 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Service Department

The Service DepartmentThe Service Department

May 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1969 -

The Scene

The SceneThe Scene

May 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Travel

TravelSpecial Report: the Moving Forces Behind Motorcycle Legislation

May 1969 By J. Bradley Flippin -

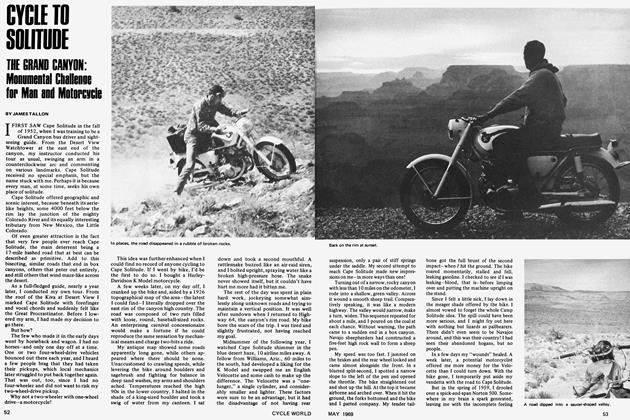

Travel

TravelCycle To Solitude

May 1969 By James Tallon