THE ASCOT HONDA

A rare article for the dirt track...

A HONDA is a rare article—on dirt tracks, that is. The clay oval sport long has been dominated by BSA Gold Star, Triumph and Harley-Davidson. Oh, once in awhile a Yamaha or Suzuki will rise to race prominence in the 250 novice class, and an occasional Honda will win a heat, but a consistent Honda 450, a bike that repeatedly makes the main event with other brand competition, is that aforementioned rare article.

Such a Honda is the property of Amateur class rider Jack Wilkinson and builder-tuner Dave Peterson. Wilkinson, a soft-spoken sandy-haired blond, is a salesman for Aragon Distributing Co., Monrovia, Calif., supplier of motorcycle trailers, tools and special racing lubricants. Peterson, a redhead and equally unassuming, is, of all things, a teacher of English in a Garden Grove, Calif., junior high school.

Friday nights at Ascot Park in Gardena, Calif., they’re racers. And, they’ve built a motorcycle that’s worthy of the game—that rare Honda.

The frame is a product of Sonic Weld (CW, Dec. ’67). The material is 4130 chrome-moly steel. The single top tube is of 1.625-in. diameter, and the two loops of the engine cradle are of 0.875in. diameter. Aluminum alloy tabs 0.312-in. thick, bolted to flanges at the rear extremities of the loops, carry the rear axle.

The front fork is of Honda manufacture. Husqvarna-type hourglass fillers are fitted within, to raise or lower the front end to suit specific track conditions. Wheels are Akront products. Tires, front and rear, are Pirelli 4.00-19s, both specially hardened and grooved to contend with the demands of dirt track surfaces. The rear drive sprocket, made by MW Engineering Co. of Pomona, Calif., is a quick-change unit, secured to the specially made rear wheel hub by four Allen screws that employ coil springs to the effect of safety wire.

Frame and suspension components all are seemingly incidental to the heart of the matter, that Honda 450 Twin powerplant. Wilkinson and Peterson have developed, rather than built, a racing motorcycle engine. Each change, each modification, each addition of a new component has been made over the span of three racing seasons on a carefully considered, one-step-at-a-time basis. And, as each change, modification or addition has been made, the performance of the machine has been thoroughly evaluated before taking the next step toward ultimate performance.

The engine is fitted with welded-up prototype 11.25:1 compression pistons, which the Wilkinson/Peterson team intends to manufacture for other Honda 450 racers. Connecting rods, crankshaft and associated bearings are standard Honda parts; the same lower end has performed the racing duties over the three-year development period.

The Honda’s breathing received most attention during development. Kenny Harman cams are used, in conjunction with standard valves, which have been chromium plated, and standard torsion arms. The degree of cam lift necessitated removal of some meat from inside the cam covers to afford proper clearances. Valve guides are specially made items, fabricated from bronze alloy, and fitted flush into the head so that the followers will not strike the guides.

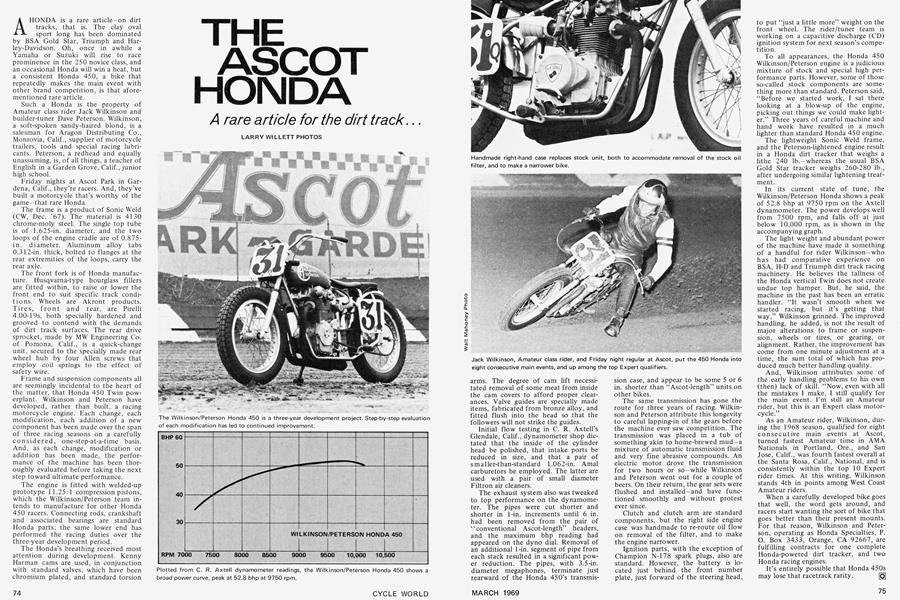

Initial flow testing in C. R. Axtell’s Glendale, Calif., dynamometer shop dictated that the inside of the cylinder head be polished, that intake ports be reduced in size, and that a pair of smaller-than-standard 1.062-in. Amal carburetors be employed. The latter are used with a pair of small diameter Filtron air cleaners.

The exhaust system also was tweaked to top performance on the dynamometer. The pipes were cut shorter and shorter in 1-in. increments until 6 in. had been removed from the pair of “conventional Ascot-length” headers, and the maximum bhp reading had appeared on the dyno dial. Removal of an additional 1-in. segment of pipe from each stack resulted in a significant power reduction. The pipes, with 3.5-in. diameter megaphones, terminate just rearward of the Honda 450’s transmission case, and appear to be some 5 or 6 in. shorter than “Ascot-length” units on other bikes.

The same transmission has gone the route for three years of racing. Wilkinson and Peterson attribute this longevity to careful lapping-in of the gears before the machine ever saw competition. The transmission was placed in a tub of something akin to home-brewed mud—a mixture of automatic transmission fluid and very fine abrasive compounds. An electric motor drove the transmission for two hours or so—while Wilkinson and Peterson went out for a couple of beers. On their return, the gear sets were flushed and installed—and have functioned smoothly and without protest ever since.

Clutch and clutch arm are standard components, but the right side engine case was handmade to re-route oil flow on removal of the filter, and to make the engine narrower.

Ignition parts, with the exception of Champion N-178 spark plugs, also are standard. However, the battery is located just behind the front number plate, just forward of the steering head, to put “just a little more” weight on the front wheel. The rider/tuner team is working on a capacitive discharge (CD) ignition system for next season’s competition.

To all appearances, the Honda 450 Wilkinson/Peterson engine is a judicious mixture of stock and special high performance parts. However, some of those so-called stock components are something more than standard. Peterson said, “Before we started work, I sat there looking at a blow-up of the engine, picking out things we could make lighter.” Three years of careful machine and hand work have resulted in a much lighter than standard Honda 450 engine.

The lightweight Sonic Weld frame, and the Peterson-lightened engine result in a Honda dirt tracker that weighs a lithe 240 lb.—whereas the usual BSA Gold Star tracker weighs 260-280 lb., after undergoing similar lightening treatment.

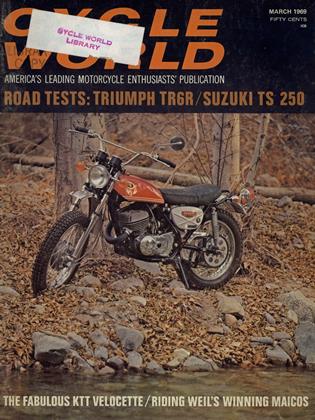

In its current state of tune, the Wilkinson/Peterson Honda shows a peak of 52.8 bhp at 9750 rpm on the Axtell dynamometer. The power develops well from 7500 rpm, and falls off at just below 10,000 rpm, as is shown in the accompanying graph.

The light weight and abundant power of the machine have made it something of a handful for rider Wilkinson—who has had comparative experience on BSA, H-D and Triumph dirt track racing machinery. He believes the tallness of the Honda vertical Twin does not create undue top hamper. But, he said, the machine in the past has been an erratic handler. “It wasn’t smooth when we started racing, but it’s getting that way,” Wilkinson grinned. The improved handling, he added, is not the result of major alterations to frame or suspension, wheels or tires, or gearing, or alignment. Rather, the improvement has come from one minute adjustment at a time, the sum total of which has produced much better handling quality.

And, Wilkinson attributes some of the early handling problems to his own (then) lack of skill. “Now, even with all the mistakes I make, I still qualify for the main event. I’m still an Amateur rider, but this is an Expert class motorcycle.”

As an Amateur rider, Wilkinson, during the 1968 season, qualified for eight consecutive main events at Ascot, turned fastest Amateur time in AMA Nationals in Portland, Ore., and San Jose, Calif., was fourth fastest overall at the Santa Rosa, Calif., National, and is consistently within the top 10 Expert rider times. At this writing, Wilkinson stands 4th in points among West Coast Amateur riders.

When a carefully developed bike goes that well, the word gets around, and racers start wanting the sort of bike that goes better than their present mounts. For that reason, Wilkinson and Peterson, operating as Honda Specialties, P. O. Box 3433, Orange, CA 92667, are fulfilling contracts for one complete Honda-powered dirt tracker, and two Honda racing engines.

It’s entirely possible that Honda 450s may lose that racetrack rarity.