VELOCETTE

When the Mighty KTT Was the Silver Single

RICHARD C. RENSTROM

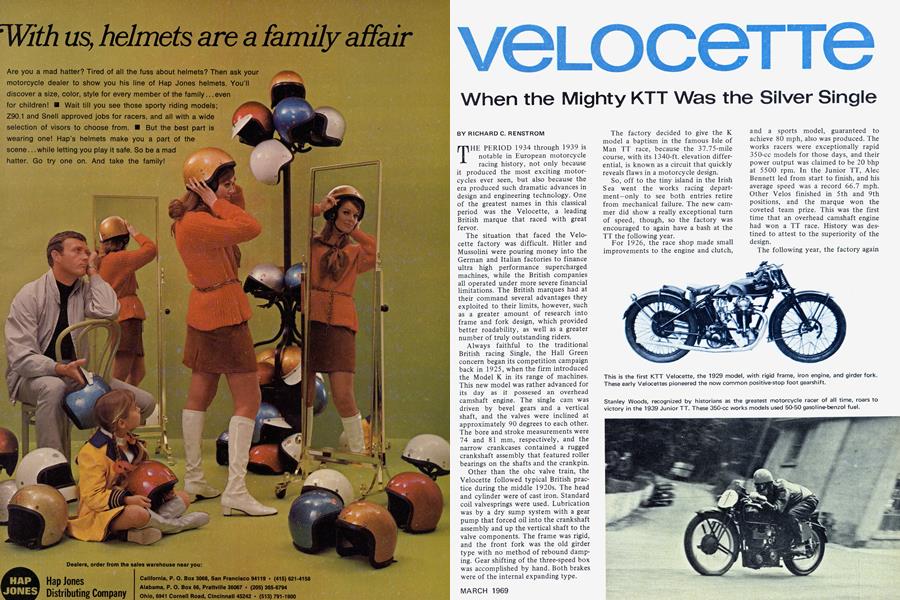

THE PERIOD 1934 through 1939 is notable in European motorcycle racing history, not only because it produced the most exciting motorcycles ever seen, but also because the era produced such dramatic advances in design and engineering technology. One of the greatest names in this classical period was the Velocette, a leading British marque that raced with great fervor.

The situation that faced the Velocette factory was difficult. Hitler and Mussolini were pouring money into the German and Italian factories to finance ultra high performance supercharged machines, while the British companies all operated under more severe financial limitations. The British marques had at their command several advantages they exploited to their limits, however, such as a greater amount of research into frame and fork design, which provided better roadability, as well as a greater number of truly outstanding riders.

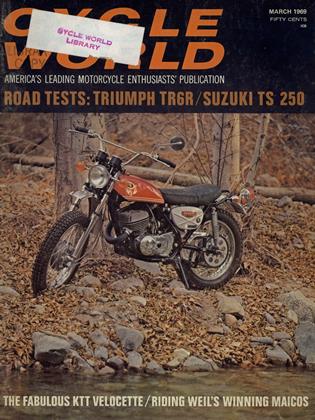

Always faithful to the traditional British racing Single, the Hall Green concern began its competition campaign back in 1925, when the firm introduced the Model K in its range of machines. This new model was rather advanced for its day as it possesed an overhead camshaft engine. The single cam was driven by bevel gears and a vertical shaft, and the valves were inclined at approximately 90 degrees to each other. The bore and stroke measurements were 74 and 81 mm, respectively, and the narrow crankcases contained a rugged crankshaft assembly that featured roller bearings on the shafts and the crankpin.

Other than the ohc valve train, the Velocette followed typical British practice during the middle 1920s. The head and cylinder were of cast iron. Standard coil valvesprings were used. Lubrication was by a dry sump system with a gear pump that forced oil into the crankshaft assembly and up the vertical shaft to the valve components. The frame was rigid, and the front fork was the old girder type with no method of rebound damping. Gear shifting of the three-speed box was accomplished by hand. Both brakes were of the internal expanding type.

The factory decided to give the K model a baptism in the famous Isle of Man TT race, because the 37.75-mile course, with its 1340-ft. elevation differential, is known as a circuit that quickly reveals flaws in a motorcycle design.

So, off to the tiny island in the Irish Sea went the works racing department-only to see both entries retire from mechanical failure. The new cammer did show a really exceptional turn of speed, though, so the factory was encouraged to again have a bash at the TT the following year.

For 1926, the race shop made small improvements to the engine and clutch, and a sports model, guaranteed to achieve 80 mph, also was produced. The works racers were exceptionally rapid 350-cc models for those days, and their power output was claimed to be 20 bhp at 5500 rpm. In the Junior TT, Alec Bennett led from start to finish, and his average speed was a record 66.7 mph. Other Velos finished in 5th and 9th positions, and the marque won the coveted team prize. This was the first time that an overhead camshaft engine had won a TT race. History was destined to attest to the superiority of the design.

The following year, the factory again raced the K model with fair success, taking 2nd in both the TT and German Grand Prix, plus a 1st in the French GP. For 1928, the K model underwent some major design improvements, and one of these was to have just as great an effect on motorcycle design as did the ohc engine. This new feature was the positive-stop foot gearshift, that made for much more rapid shifting, as well as increased safety because one hand now was not required to be removed from the handlebar to change gears.

In 1928, Alec Bennett again won the Junior TT at record speed, and became the first with a 350-cc engine to lap the course at over 70 mph. Other Velo riders secured 2nd and 5th, as well as a smashing victory in the Ulster Grand Prix. The year ended with a successful record attempt and, at 100.39 mph, the Velo became the first 350-cc model to average over the “ton” for 1 hr.

The following year, the marque again set a trend when the manufacturer announced that it would produce a pukka road racing bike for sale to the private owner. Named the KTT, the new model was the first genuine British racer ever offered for sale, and other companies soon were to follow this lead. The KTT had the tried and proven cast iron ohc engine, with a 7.5:1 compression ratio, and a 1.062-in. carburetor. A footshift, close ratio gearbox was used, and the rigid frame, with a 53.75-in. wheelbase, was retained. The bike weighed a light 265 lb., and the maximum speed was 85 mph on a 5.25:1 overall gear ratio.

In classical racing that year, the works team did well, with Freddie Hicks winning the Junior TT and the French and Dutch grands prix. Other Velo riders took 3rd, 5th, and 6th in the Junior TT; and Hicks brought his little 350 home 6th in the big Senior TT for 500-cc machinery. The production KTT also did well by taking 1st, 3rd, 4th, and 5th positions in the Manx Grand Prix. By then, the racing world had taken notice that the pushrod engine had truly met its master in the new ohc.

About that time, the terrible economic depression struck Europe. Sales of motorcycles began to decline sharply. Racing activity naturally took a back seat and, after taking the first eight places in the 1930 Junior Manx Grand Prix and a 1st in the 1931 event, the factory reduced its racing campaign to a very modest level.

In 1932, the race shop turned out a new works racer that had an aluminumbronze head with a downdraft intake port. Hairpin valvesprings also were used in an effort to better control the valves, as engine speeds had risen to 6000 rpm. A new four-speed gearbox was used, and a larger 3.5-gal. fuel tank was fitted. These modifications also were incorporated into the MK IV KTT, an exceptionally fine model that was capable of

95 mph on the 50-50 petrol-benzol fuel used in the prewar days.

In 1933, the race shop increased its activity a bit more with some engine modifications. A new single-tube frame made the racer more competitive. Velocette won the French, Brooklands and Manx grands prix, as well as taking 4th, 5th, and 6th in the prestigious Junior TT.

The marque made a great stride forward in 1934, as the world climbed out of the depression. Sales were on the increase and greater profits meant more money on which to operate the race shop. Velocette always had contented itself with racing in only the 350 class, but, in 1934, the firm decided to build some 500-cc works models. Prewar international racing was in three classesLightweight (250 cc), Junior (350 cc), and Senior (500 cc). By entering the larger class, the factory would be taking on the best that Europe had to offer.

In 1934, works bikes were very fine road racing machines. The new 500-cc Velos had a bore and stroke of 81 and

96 mm, respectively. A new cradle frame was designed and the powerful 1.5by 7-in. brakes were housed in massive conical hubs cast of magnesium

alloy. The cylinder and head both were of aluminum alloy. The cylinder carried a cast iron liner.

The 500-cc Single made a successful debut with a 3rd in the Senior TT and a win at record speed in the Ulster Grand Prix. The 350-cc model also did well with 4th through 10th places in the Junior TT, 2nd and 4th in the Ulster, and 1st in the Swedish and French events.

The following year, the MK V KTT model was produced. This machine featured the cradle frame and the metered jet lubrication to the lower end, bevel gears, and cams identical to the works racers. The success in racing was about equal to the previous year.

During the middle 1930s, the competition in grand prix racing became extremely intense. The prewar formula permitted supercharging. Horsepower be-ing developed by the German and Italian marques made the British rather apprehensive. With this to motivate them, the British responded with some new bikes that were faster, as well as more roadworthy.

One of the greatest leaders during this era was the Velocette. This was particularly true when the 1936 works racers rolled out of the shop. Spurred on by the win of the Italian Moto Guzzi in the 1935 Senior TT, the first non-British victory since 1911 and the first win by a spring frame motorcycle, the new Singles featured swinging arm rear suspension. This frame is virtually identical to those used by nearly all the world’s manufacturers today, and it used air-oil shock absorber units that were pumped up to the desired pressure. An air scoop was provided for cooling of the front brake. The 350 model was fitted with a dohc head.

These new works models were tremendously successful. Stanley Woods was edged out by only a few seconds in the Senior TT by Jim Guthrie on a Norton. In the 350-cc class, Ted Mellors garnered many victories to bring home the World Championship to Hall Green. The final race of the season, on the fast Swedish course, showed the handwriting on the wall, however, when Otto Ley and Karl Gall trounced the field on their 500-cc supercharged BMWs.

During the winter, the British frantically searched for more performance from their Singles. Harold Willis at the

Velo works developed new single-cam powerplants that had massive 9-in. square heads and a huge barrel cylinder. The compression ratio was upped to 10.9:1 on the 350 engine and about 10:1 on the 500 model. In an effort to control valve float, the adjusters were done away with and the valve gear lightened by using eccentrically mounted rocker arms, and reliability was increased by use of an improved lubrication system that pumped 1 gal. of oil every 6 min. The inlet port also was inclined more steeply, and the float was remotely mounted on the oil tank to prevent fuel frothing.

These new Singles were magnificent road racing machines, with the 350 churning out 32 bhp at 7200 rpm for a top speed of 117 mph. The 500 developed 42 bhp at 6700 rpm for 124 mph. Woods once again lost the Senior TT to the Norton by only a few seconds, and Mellors once again dominated the Continental races to garner the 350-cc title. The supercharged BMW Twin, however, was clocked at 145 mph and it, and the blown Gilera Four, won five of the Senior class races.

For the 1938 season, the factory made only minor improvements to the works racers and brought out the 350-cc MK VII KTT model for the private owner. The new KTT was powered by an engine almost identical to the works model, but the frame was still rigid. The works team faired exceptionally well that year in the 350-cc class, with wins at the Isle of Man, and in the Ulster, French, Dutch and Italian grands prix. In the 500-cc class, the British Velocette and Norton Singles were overwhelmed by the BMWs in all but the Senior TT, in which the superior roadability of the thumpers manifested itself on the many corners of the circuit.

The final year of prewar racing was 1939, and it certainly must go down as the greatest and most exciting year in international motorcycle racing history. All the technical knowledge that the German and Italian factories had gained in development of their supercharged machines was put squarely on the starting grid in the form of tremendously powerful machines. The British fought back

At the Hall Green works, it was obvious that increased rpm and better roadability would be required to hold off this supercharged competition. The first step was a new and stiffer crankshaft assembly, plus some other small engine modifications aimed at additional speed. The second step was to produce the MK VIII KTT. This new 350-cc Single was nearly identical to the works models. The MK VIII was historic in that it was the first bike with a swinging arm suspension sold to the public. It proved a truly great racing motorcycle.

The lineup that challenged the British at the start of the 1939 season was awesome, an array of machinery that was certainly the most classical to ever grace the colorful grand prix courses. In the Junior class, the Velo was forced to contend with such models as the blown DKW two-stroke that produced no less than 56 bhp from its water-cooled powerplant, the 65-bhp NSU Twin, and arch-rival Norton and AJS Singles. The Senior class included the 78-bhp BMW Twin, the fabulous supercharged and water-cooled 90-bhp Gilera-Rondine Four, the blown 90-bhp NSU Twin, and the supercharged DKW and AJS Twins and Fours.

About the only thing in favor of the British was that their thumpers, at 325 lb., were up to 100 lb. lighter than their supercharged competition, and their research into frame and fork design produced bikes that could be hurled around corners much faster than the cumbersome blown multis. Twisting up the wick on a 90-bhp motorcycle does take a great degree of skill and finesse, and abuse of the throttle meant abrupt disaster.

The season began with the June TT races, and in the Senior event the BMWs of Georg Meier and Jock West humiliated the best of the Norton and Velocette riders. The Junior TT saw a tremendous battle with Stanley Woods edging out Harold Daniell’s Norton and Heiner Fleishman’s DKW.

The remainder of the season was simply a calendar of epic battles between fine handling Singles and the blown multis. In the end, Dario Serafini was crowned 500-cc Champion on his fantastically fast Gilera-Rondine, which had been clocked at 150 mph on the 7-mile Clady Straight in the Ulster Grand Prix. The Junior Class again had the MK VIII KTT on top, but the DKW riders came very close to unseating the champion.

By then, it had become obvious to Velocette, as well as to the other leading British marques, that some supercharged multis must be developed if these factories were to remain successful in classical racing. Accordingly, the factory designed a new 500 Twin, but then came the war and racing was shelved.

After the war, the FIM instituted a new formula that prohibited supercharging, and the fabulous battles between the blown beasts and the superb Singles became just pages of the history books. Velocette continued to race the prewar Single with the compression ratio lowered to accommodate “pool” gasoline. These machines dominated 350-cc racing until the firm lost interest in the game early in the 1950s.

While it is true that the Hall Green racers were very successful in the postwar years, particularly with their fast 350-cc dohc works models in 1949 and 1950, something was lost from the colorful prewar days. Perhaps it was lack of truly great engineering advances such as the early KTT introduced, but more possibly it was the lack of an intense international struggle between brute strength and superb handling. There was something about the beautiful bellow of a big Single mingling with the drone of a blown Twin or the screaching howl of a supercharged Four that made the blood tingle. At no time since 1939 has the grand prix heard such beautiful music from motorcycles.

During this period of colorful bikes, there was one production racing machine that stood far above the others for its performance, reliability, and engineering excellence. This was the MK VIII KTT—the beloved 350-cc Single that won 37 Silver Replicas in the 1939 TT races. That was more silver than was won by all the other makes together, and it certainly reflects the esteem that the European racing man had for the Velo in the prewar days.

The 1939 KTT model could be termed a very basic design developed to a high level of performance. Rather than develop radical features that would prove troublesome or temperamental to the private owner, the emphasis was on a good performance combined with fine handling and reliability. The end result was a 350-cc engine that developed 32 bhp at 7200 rpm on a 10.9:1 compression ratio. Maximum speed was 110-112 mph, which was a very respectable speed in those days.

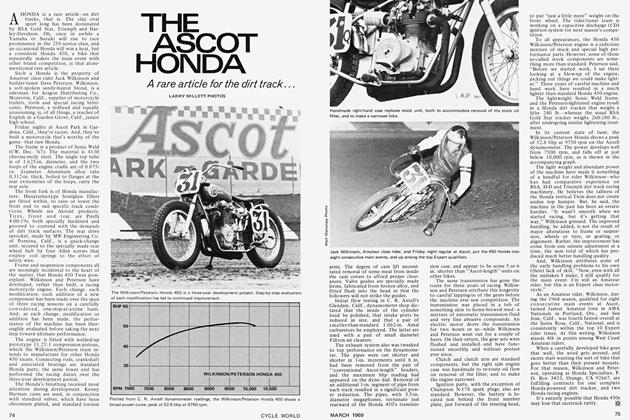

The crankcases of this engine were cast of aluminum alloy, and they were very narrow to provide great rigidity. The two steel flywheels had pressed in shafts with the roller-bearing crankpin pressed in on tapered holes. The forged connecting rod was mirror polished, and the small end bushing was bronze. The sand-cast piston was steeply domed and with pockets to clear the valves.

The cylinder and head were both massive aluminum alloy castings with deep fins to dissipate the heat. Cylinder liner and valve seats were all inserted. The intake bore was 1.156 in., with large 1.562-in. and 1.437-in. intake and exhaust valves. Valve control was by hairpin springs—chosen for low profile, which allowed space for a higher port, and for the better valve control. The drive to the single cam and two rocker arms was by two pairs of bevel gears and a vertical shaft. Ignition was by magneto, and lubrication was by a gear pump with metered jets to the crankshaft, bevel gears, and cams.

The frame used on the KTT was a cradle type with swinging arm rear suspension. The shock absorbers were Dowty air-oil units, in which the air resisted and the oil dampened on rebound. The front fork was of the girder type, with a coil spring. The brakes were finned and air-cooled, and were mounted in massive conical hubs cast of magnesium alloy. The gearbox was a four-speed unit with ratios of 5.0:1, 5.5:1 and 9.6:1.

The tire sizes were larger in diameter than those in use today. The rear was a 3.25-20; the front was a 3.00-21. The wheelbase was 53.25 in. Dry weight was 330 lb. The KTT had behind it a great amount of research in frame design. Even today, these machines would be appraised as very fine handling motorcycles. It is only on rough roads that the older suspension compares poorly with modern machines, as the two-way hydraulically dampened telescopic fork has proven vastly superior.

Altogether, these old KTTs were splendid racing machines. Their speed, stamina and roadability easily made them the most outstanding production racers of the prewar era. Very few of these fine Singles ever made their way to North America, probably because they were not “legal” under AMA rules that governed U.S. sport during the prewar and postwar days. Another factor was that European style road racing has only recently become popular in this country.

There are, however, four known KTT models in North America—one in Canada and three in the U.S. One of these KTTs came into this writer’s possession 10 years ago after a three-year search in Oregon to locate it. And, 10 years have gone into restoration of the bike to show condition, the time a result of lack of finances and the necessity to advertise for parts in European magazines. These KTTs are much sought after by collectors the world over, and parts have become nearly impossible to obtain. Arthur J. Mortimer, editor of the Vintage Motorcycle Club of England’s magazine, recently reported that, in his opinion, the KTT is possibly the most sought after classic in all of Europe.

So, today, in Idaho resides a machine out of the past—a chapter in motorsport with which few Americans are familiar. It is a great saga. The KTT’s beautiful engine castings, and those magnificent brakes recall the great thunder of its exhaust on the drop down to Creg-NyBaa. In the distance is the scream of the supercharged Güera Four, the howl of the BMW, and the crescendo of a Norton as it shifts gears. History lives in the KTT.