Motorcycle Touring in MOROCCO

CHRISTIAN WILLIAMS

WE WERE GRINNING at the end of it, after 1000 miles through 'Morocco, but sorry our motorcycling adventure was over.

It felt good, after five days of hard riding, to coast down the last scarred mountains from Tetuan and onto the treestudded Plain of Tangier. The warm North African sun followed us low on the left, a welcome companion after the chill of the mountain heights. The fine road, nearly empty during past days, began quickly to fill with familiar wagons and burros as we neared the outskirts of Tangier. Herds of white sheep, their young shepherds waving, surged onto the highway as if in welcome. When the stern traffic policemen motioned us into the traffic of the strange city, it was like coming home.

Later, kicking red mud off our saddle-

bags, we realized for the first time everything we had almost missed.

Like most Americans headed for Europe, we had barely known Morocco's position on the map. We did not know that the kingdom of Sultan Hassan II is the next great frontier of motorcycling adventure, a country nearer than Europe, cheaper than Spain, and foreign beyond imagination.

This frontier, like the frontiers of the past, is steadily receding. Morocco is fascinating because it is primitive, but its people are working toward a better way of life. Soon prices will rise. Already this ancient Arab country, so unlike modern Europe, is seeking its share of big-time tourism.

Today it is possible to explore this land of crumbling casbahs, veiled women, and unspoiled natural beauty on a budget in which pennies count.

The five-day tour that ended our stay in Morocco cost us $44.30, including gasoline. From February to May, my wife Betsy and I lived in Tangier, in a two-

room apartment with bath and kitchenette, for $40 a month. We cooked huge meals for less than a dollar a day, and laughed at Arab films with French subtitles for a charge of 10<^. We found a double room in the exotic Hotel Carlton costs $1.20 per day, and that a delicious meal of a dozen shish kebabs can be had for less than a pack of U. S. cigarettes.

All this is in a city that is $180 away from the piers of Brooklyn on the luxury freighters of the Yugolinia Line. Fifty dollars additional brings a motorcycle. In Tangier, tourists couldn't be closer to Europe; 10 miles across the Strait of Gibraltar loom the dark mountains of Spain.

Morocco, however, because of the barrier of the strait, has, until now, remained virtually uninfluenced by the continent. Though its cities are modern enough, life in the country continues much as it did 200 years ago.

The result is a motorcyclist's paradise of endless, perfect roads of every grade and description, all but empty of cars. There are snow-covered mountains, palmfilled valleys and hundreds of miles of sandy, uninhabited Atlantic coastline. Yet, surprisingly, American motorcyclists bound for Europe have for many years missed the call of this unreal Arab country.

Tangier, on the far north tip of Africa, is a small, hilly city, sprawled over a curve of white sand beach. Its medina, or old native quarter, supports — besides a large Moroccan population — a growing colony

of European writers, artists and beats.

With its people in veils, sandals, and the flowing robes of the traditional jelloba, a hooded outer garment, Tangier seems at first not to have earned the unenviable reputation it gained after World War II. But things haven't changed that much. Smuggling from duty-free Gibraltar still prevails, and sale and use of the narcotics, kif and hashish, flourishes.

People are friendly, and their hospitality is legendary.

We arrived lacking a motorcycle — our first mistake. Bikes are not available in Morocco, for several complex reasons, but a helpful information officer at the American Legation suggested we try Gibraltar — the "Rock" — a 2.5-hour ferry ride up the strait.

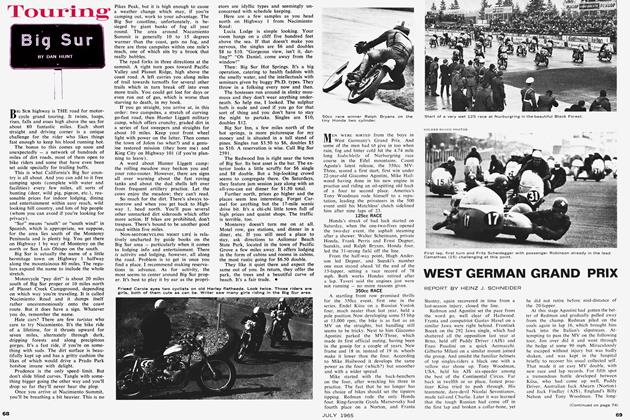

In a day's work, I inspected every bike shop on that beleaguered British outpost, and found prices good but the selection terrible — a result of the latest political clash with Spain. I had some luck, however, and returned to Tangier the next day with a 1-year-old BMW 250 with 6000 miles on its odometer. The price: $360. It turned out to be the perfect choice.

We settled quickly into life in Morocco, where time seems to lose importance. Betsy began to learn the rudiments of bargaining in the overflowing public markets. We swam in the clear water of the strait, ate exotic five-course dinners in the homes of our new Moroccan friends, and partied with the viscounts and countesses in exile

from the rising living costs of Europe.

Everywhere we went, people urged us to see the south country, the "real Morocco," the fabled cities of Casablanca, Fes, and Marrakech. We bought maps, made plans and lost track of the passing months.

Every day Betsy returned from shopping trips carrying oranges as big as coconuts, fist-sized lemons, perfect limes, artichokes, strawberries, bananas, and avocados. On our decimal-point budget, we cooked huge cuts of beef and mutton on a charcoal brazier, watching the sunset from our tiled rooftop.

There were difficulties, of course. In Morocco, even Tangier, little English is spoken. Arabic, French, and Spanish prevail in the north. My strangely unrecognizable Spanish — and pointing — sufficed. We were harassed by beggars and pitifully diseased boys, who cover the countryside under the protective cloak of Islam, the religion of Morocco. We withstood the assaults of armies of shoeshine boys, probably the most obnoxious young gentlemen in the world.

But it's just this non-tourist center atmosphere — regardless of what the Moroccan government says — that keeps the prices down. So we grinned instead of cursing, and it seemed to work.

Tangier is filled with motorcycles so small their engines could be put in a pocket. Forty-nine cc are considered fearsome power. Mufflers are ripped off the day of purchase, however, and the result is deaf-

ening. Those mini-motors work hard, too. Somehow, moped trucks succeed in pushing their loads of six 50-pound bottles of cooking gas up 17-degree hills. To top it off are the police, who ride BMW R-69s, moustaches flying, gold teeth glinting, and scare everybody out of their wits.

From a base in Tangier there are two fine trips to be made, perhaps in the same day. These are to the caves of Hercules at Cape Spartel, and to the lighthouse and Moorish castle at Cape Malabata. We commuted between them, tuning the bike for the long trip south. Then, one sunny morning, we turned a gentle corner and ran head-on into the front of a speeding Volkswagen.

It was the driver's fault, but that turned out to make very little difference in the end. He had come around the corner without looking, and found the front wheel of the BMW climbing his hood. I woke up half through the VW's front windshield, but Betsy, riding behind me, had a longer flight. We weren't hurt. A crowd of about 300 gathered, and someone started selling peanuts. Really!

Later that afternoon, glowing with patches of iodine, we rattled over to appear at the police station as ordered, expecting to find the compulsory Moroccan insurance laws working in our favor. Instead, we found a tangle of red tape . . . in Arabic and French. Our interpreter happily explained that he thought "nothing worse would happen in that we would explanation." We filled out the forms and made it out of there, having waived our right to appear before the tribunal. "Oh well," we said.

Motorcycle mechanics are hard to come by in Tangier, but we found one. He fixed the bike and took us to the movies. Then he took us on a tour of the city in his car. Then he took us to Cape Malabata for mint tea. He paid all the bills. The charge for a day's work on the BMW? A little over $6.

Two days later, after a successful test ride, we left on the grand tour.

We had been warned of wilderness, and were prepared for it. But extra cans of gas proved unnecessary, as all but the smallest Moroccan villages operate a kind of fuel station. We missed the tube and tire repair kit, which we were unable to obtain in Tangier, and would not go again without one. Our helmets, shipped from home, were welcome after the bare-headed accident. The windshield earned its keep from the first day — Morocco teems with insects that resemble flying walnuts. Also needed is a good guide book. We used the Hachette World Guide to Morocco, available in Tangier, and found it good, but expensive, at $6. Its fine maps, however, proved invaluable.

Casablanca, the fabled city 230 miles down the Atlantic coast, was our goal the first day. At a steady 55 mph, we glided southward along some of the most perfect roads in the world, passing empty beaches where surf crashed and rolled like thunder. Dodging rainclouds, we slipped in and out of peaceful Moroccan towns such as Asilah, Larache, and El Ksar el Kebir, where the residents yelled and waved in greeting. It was a fine day of easy riding.

The BMW behaved beautifully and immediately sold me on the idea of touring

with a 250 cc. With two up, it had an honest top speed of 70, totally free of vibration. Gas consumption was somewhere between 70 and 80 mpg. It was like riding an easy chair with leading link suspension.

Two golden rules of inexpensive travel are: Forget about a private bath in hotels, and picnic whenever possible. So, strapped to our arnj.y-navy store canvas saddlebags was a gourmet's delight of sardines, cheese, bread, wine, and olives. We ate it in a sea of wildflowers after 130 miles of travel, looking over a herd of grazing mountain sheep. When we pulled into Casablanca, a huge, modern industrial city, we broke the first rule. But the steaming shower was good, although it doubled the price of the room to $3.70 for two. Later, we ate a four-course meal of French cooking in a restaurant for $1 each — just to keep spirits up.

Marrakech, another 200 miles to the south, was the destination the second day. We bought picnic supplies again and set out into the desolate countryside. There were no cars on the roads, and it was hot for the first time during the trip. We passed the remains of a jackal lying in the road, surrounded overhead by a vortex of feasting vultures. We went 100 miles without seeing a car, and I began to worry about flat tires.

After noon we became hungry, and took to the dirt. In the high, red plain that lies north of Marrakech, we climbed a crumbling path, parked the bike, and uncorked the wine. The guidebook revealed that this was the Rehama Plain, "a semi-desert region of little vegetation." We felt secure enough with our full gas tank, and content with the loneliness in a country where Americans sometimes find themselves too much the objects of curiosity. The harsh red hills swept away from our high picnic spot in every direction under the low. swirling sky.

We were watching the rain move toward us from the east when a ragged boy came over the nearest hill at a gallop, three white eggs in each hand, his little brother breathless behind him. They wanted us to buy the eggs.

"La," I said, "No." The younger urchin burned his hand on the exhaust pipe of the motorcycle, then looked at me in accusation.

We wound up buying the eggs and then giving them back, after explaining that they would break in the saddlebags, where the older boy had put them after I said I didn't want them. It's often easier to buy than refuse in Morocco. So the youths got their eggs and the price of them, too.

Three hours later, we climbed a low mountain pass and sped down into a green valley of palms . . . Marrakech. Following the tall minaret of the famous Koutoubia Mosque, a beacon over the low city, we beat the rain into the old section.

Most Moroccan cities present two faces to the visitor: a "new town." built by the French during their administration of the country, and a medina. Invariably, the medina — often thousands of years old — is more interesting, more alive, and dirt cheap.

Our room in the Hotel Central in this part of Marrakech cost 70ç each, and the friendly owner helped us lug the dripping

motorcycle into a neat courtyard filled with glistening palms. Then we pushed off into the twisting alleys for a three-course meal at 5 dirhams — about $1.

The capital of southern Morocco, Marrakech, is a metropolis of the Berbers, the rough mountain tribesmen who originally inhabited the western part of North Africa. Overall, the city is red in color — a product of the mud and straw construction that is used for many of the buildings. Encircling its 270,000 people are the snow-capped peaks of the Atlas Mountains, their gray bulk framing the city's dense palm groves.

The markets, alleys, and atmosphere of Marrakech are famous, but probably the best known attraction is the Place Jemaa el Fna, an open square in the medina where native musicians, story tellers, dancers and pickpockets provide continuously lively entertainment. We watched with awe as a group of 20 Saharan drummers held a circle of 250 people speechless with an incredible performance of ear-piercing noise.

We explored, with the help of a "free" guide, the ruins of the El Badi Palace, built by the Saadian sovereign Ahmed el Mansour in 1578. Most of what remains are subterranean dungeons — reserved, our guide told us, "for those who talked too much against the sultan."

The city is filled with horse-drawn carriages, braceleted desert women, and bicycles. The prices are half of those in Tangier. A hot glass of mint tea costs about 5<t in the steamy cafés. And the sky covers everything like an endless blanket.

After 2 days we itched to be on the road, to ride into the high mountains that loomed around the walls of the city. We located the route to Fes in the maze of twisting streets, and headed northeast.

After about a mile, a wasp the size of a hamburger flew into my forehead at 60 mph, having slipped between the helmet and the windshield. As my head became swollen, the helmet rose like a successful sponge cake. We finally had to stop until I could get my hat size back to normal.

The Fes road is two lanes wide and perfect, but the engineers couldn't make it very straight because it parallels the Middle Atlas Mountains for 200 miles, and then begins to jump from peak to peak. The distance is 302 miles.

It was cold when we left Marrakech, and my hands quickly formed into claws around the grips. We could see hard rain falling in the distance. The road was good and we wanted above all to stay dry, so I pushed up the speed.

There is a strange, exciting freedom to driving a good motorcycle fast, and knowing that there is a great deal of ground to cover before the end — a feeling that people who drive Buicks and Cadillacs don't understand. We enjoyed the small mud and straw combines, surrounded with their high beds of prickle bushes. Several times I hit the brakes hard to avoid huge camels loaded with hundreds of pounds of broken sticks, as they stepped into the road ahead of us. The 12-ft.-tall animals often filled the entire passage across oneway bridges. We kept up speed, however, because the chill was beginning to turn the pleasant ride into an endurance run.

Rounding a bend at 60 mph, I pointed

to a surprisingly realistic mirage ahead. The road seemed to be covered with red water. I jumped on the brakes when I discovered that it really was red water. We puttered through. It was quite deep, and would have thrown us, had we hit it at speed. Hospitals are few in Morocco, so we maintained 55 mph afterward.

Eventually, the sun broke through the clouds, and we picnicked on bread, dates, olives, and cold tea.

The small villages passed more quickly, it seemed, under the warming sun — Beni Mellal, Kasba Tadla, and El Ksiba, where the hills start in earnest. Once into the mountains, the outlook changed. With the road twisting like a snake, we held on and rode hard.

The climb upward to Ifrane, toward the end of the day's ride, was a steep one, and a test of any bike's power. The town is chiefly a resort, a kind of hill station at 5400 feet on the side of a craggy branch of the Middle Atlas. It was there I expected to curse the mere 250 cc driving our rear wheel. But the BMW would have none of it. We held 30 mph up the most challenging inclines, with two up and 50 lb.

of gear aboard. Most of the turns exceeded 90 degrees, seeming to shoot straight up at the same time, so higher speeds would have been impossible. Our simple carburetor, tuned for touring, was not upset by altitude. The 250 cc were enough.

High on the plateau we encountered rain, wind, and freezing sleet. Crouching behind the windshield, we saw that natives of the mountains wear two or three je Habas, even in late spring. But our shivering was rewarded occasionally when the clouds parted around us to reveal delicate green patchwork fields thousands of feet below, where we were headed.

The long descent required more than an hour, and on wet roads we swallowed hard at every blind, gravel-covered turn. In the valley it was 20 degrees warmer, and the sun was shining. Wet, cold, sore, and covered with liquid clay, we sped into the famous city of Fes, feeling good.

Fes, with its Arab University, ranks as one of the important educational centers of the Islamic world. Its medina is probably the largest and best preserved in North Africa. But we saw little of it. People who have been around will warn

against drinking the water of a foreign city, because it will frequently induce a special kind of sickness. But bottled water is expensive — often more than wine. And hotels insist their tap water is simply tasty, not dangerous. You either decide to drink seltzer or take your chances. After taking our chances for 4 months in Morocco, we became ill in Fes. It was a long night . . .

We did not know it at the time, but the road from Fes to Tangier, via Ketama and the Rif Mountains, makes the Isle of Man look easy. Feeling like the Green Bay Packers on a Monday morning, we nevertheless climbed back on the motorcycle the next day and pushed off. The run was to be fairly short — 275 miles.

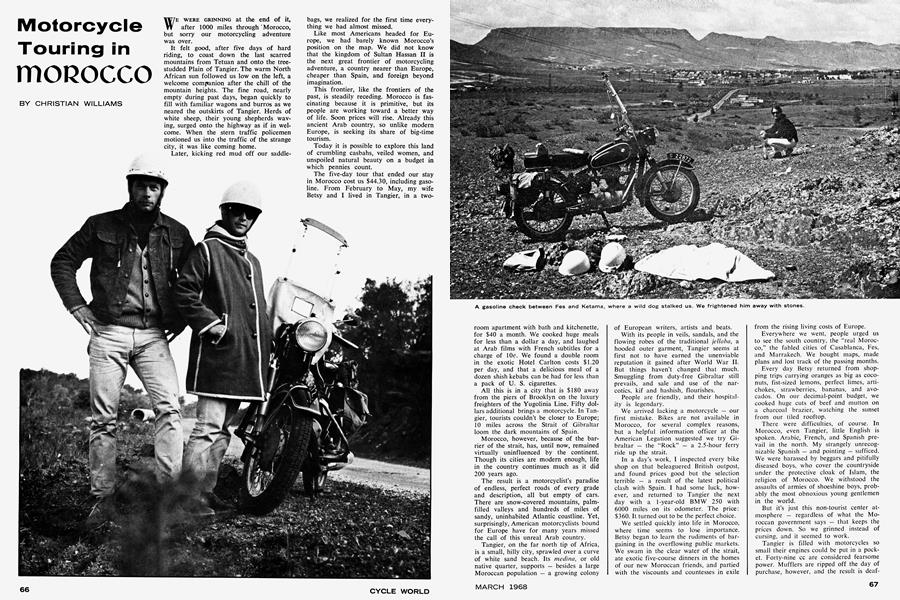

As we headed for Ketama on the Route de L'Unité, which connects central Morocco with the Mediterranean coast, we were smiled upon by two large policemen, standing by their shiny machinery. We wondered about that.

Leaving Fes, the road is high, wide, and handsome. At the city limit it changes to dirt, then to pavement, then into some-

(Continued on page 78)

thing in between. Gradually it improves, but becomes vertical — or nearly so.

The next 200 miles was through the kind of wilderness scrambles fans dream of, but we kept our wheels on the thin strip of road surface carved into the countryside, and were the only travelers on it most of the way.

This was a ride never to be forgotten. The turns came up so fast and hard and often that each shoe was scraped on the pavement about ten times a minute. Back and forth and up and down, until the rhythm and the smoothness of the road nearly induced sleep, despite the aching arms. The road couldn't be driven fast

without burning out brakes, but it didn't seem to matter. There was a tendency to sing.

We motored up into the clouds and down into green valleys again and again, and sometimes we could see the road ahead for 20 miles, where it cut along the edges of the cliffs. At the top. we reached

(Continued on page 81)

Ketama — where there is, for the record, no gasoline.

From there the work was negligible. We had reached the east-west ridgeline of the Rif Mountains, which the road to Tangier follows. From Ketama's cedar forests, there are glimpses toward the Mediterranean, 7000 feet below. There is also legal kif, a marihuana-like weed. We were offered a pillowcase-full for $2.

Deep in the Rif we cashed our last petrol coupon, at a rusty gas pump which managed to cover the two of us, the motorcycle, two ducks and 5 sq. ft. of soil with low-grade fuel. All for 5 dirhams. Moroccan gas pumps are something. (Petrol coupons, available in Tangier, are bought for 7 dirhams, but have a value, in Moroccan filling stations, of 10 dirhams.)

We arrived in Tetuan, the final city before Tangier, about 5 p.m. that last day. There was one small range to cross through the jagged cliffs, and we headed for it.

The last few hours seemed the longest. Squirming like worms on a hook, we were determined not to stop until the sea hove into view behind Tangier. I was thinking about hot food, when two gray-clad motorcycle policemen walked casually out of a bush and into the center of the road.

"Passports, please. Insurance. International driver's license. Registration. Bill of sale." The two young men, resplendent in knee-high boots and green helmets, read carefully over the documents, which were in English. They they asked questions, in Arabic. I smiled. They did not. One of the officers stroked his great black moustache and waved us on.

I couldn't get it to start. Kick, kick, kick, kick. Suddenly "black moustache" removed my arms from the handlebars, grabbed the BMW, and began to run. I said, oh no, really, I couldn't allow this, but he was off. While his silent companion watched, he charged down the road, pushing. If a spark plug can be unfouled by sheer muscle, he was capable of doing it.

After 500 yards he was back, bowing and grinning with pride. The two of them helped us onto the purring bike and bowed again as we took off. Then they went back to sit on their motorcycles until someone else came down the empty road.

The 1000th mile ticked off as we entered Tangier. Our planned stay of 1 week in Morocco had become 4 months, and it was time to start planning again.

Already, we began to remember the red city of Marrakech; the perfect, twisting roads of the Rif; the running shepherd boys who put eggs in our saddlebags; freezing rain at Ifrane and Azrou; and blazing sun of the desert-like Rehama Plain.

We also thought, sitting down to a steaming pile of spaghetti in our apartment, of a strange meeting high in the icy mountains when we passed, in a narrow curve, another motorcyclist, leaning into the turn. His brief, comradely wave before he leaned the other way, speeding past, and disappearing behind a rocky ledge, made us feel that there ought to be more of that sort of thing in Morocco.