Christian Williams

WE MIGHT AS well face up to it (just among ourselves, of course. No sense making trouble at the dinner table): While we sometimes pretend that long trips on a bike will get the urge out of our systems, the truth is just the opposite. Taking a short trip means planning a second longer ride, which frees your imagination for planning a third tour, a real long one this time.

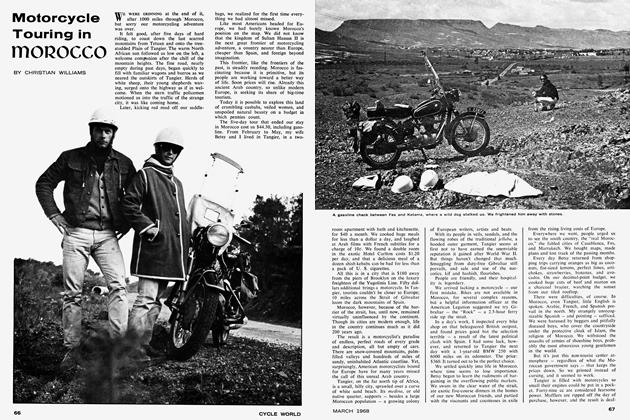

This was brought home to me on the road from Fez to Ketama several years ago. While a BMW 250 hummed smoothly underneath and the eerie Moroccan mountains rose higher and higher all around, all I could think of, damn the luck, was what it might be like to ride from New York to California.

Wondering what the Rockies might be like, whether the Denver or Southern route might be better, and how long it might take, was as much fun as the wonders of Casablanca, Marakesh and couscous. Imagination is a fine thing.

And the memory of those magnificent two-or-three-day trips lingers: The runs at dawn along deserted roadsteads thinking of ham and eggs; the thundersquall that followed at a distance that humid afternoon but never struck; the sunset forest passage when the bike, passing through the clouds of evening mosquitos and in and out of the first cool waves of nighttime air, quietly hummed the, er, Song of the Road, or whatever you call the tune engines hum.

Naw, if you like to ride, you now and again are going to want to go someplace. This hanging out at the cafe comparing pin stripes wears thin, eh?

To take a several-thousand-dollar 750cc machine to the drugstore to buy a snow cone is treason against the free spirit of highway America. When you buy such a motorcycle—I feel sure there will be no dispute here—it’s an implied commitment, hell, it’s a regular straightforward flatout promise to yourself and your loved ones that you’re going someplace. Long distance travel! To see what’s over the next range of apartment buildings, to cross the desert and the fruited plain, to crash the barrier of the weekend trip, to boldly go where no man has gone before on a twoweek vacation!

To go cross-country!

Coast to coast is about 3000 miles. Figure 300 miles a day, 10 days. Most people do better than that, which gives, them time at the other end, and allows a few stopovers en route.

The trouble with actually planning tours', as opposed to imagining them, is that reality intrudes. Yes, you may live in Texas and daydream your way to the Great Lakes with never a second thought. But lay out the maps and the credit cards, and the problem appears. By gum! You gotta drive back!

The long-imagined journey of 1000 miles becomes one of 500. The trip to Alaska evaporates, the cross-country trip stops at Chicago. Enthusiasm pales. Precious vacation weeks seem to disappear in the day-count necessary for the return ride home, and the whole project slips away into unlikelihood.

Getting back is the problem. The round trip is 7000 miles plus, and who’s got a month’s vacation?

The solution is simple: When you gel where you’re going, fly home and ship the bike back. This offers the freedom to make any of the fine expeditions ever imagined in half the time. It will cost less than round-trip air fare, and the experience will be immeasurably richer.

At least that is what Betsy and I found to be true after a 4200-mile run from New York to Los Angeles and San Francisco. On the 12th day of our travels (New York to Los Angeles took eight days and included a layover in Aspen), we drove to the San Francisco docks, filled out a form, wrote a check for $180, said goodbye to our Honda 750, and took a taxi to the airport. The next day we were back at work on the East Coast, as if nothing had happened.

THE ONE WAY TRIP

Ten days later the bike arrived, none the worse for wear.

Will every shipper handle bikes? No. The trick is to find a freight handling company (that’s the Yellow Pages category) which is willing and able to crate your bike where you leave it, then ship it where you want it to go.

One such company is World Wide Export in San Francisco, located at 2345 Third St. It was World Wide that shipped our cycle, and it seems that whatever we told them, they replied, “No problem.” I’m not saying there’s never a problem, but they do want the business. Contact Ernest Baigorria. A recent quote gave a crating charge of $ 1.50 per cubic foot. If your bike needs a box 3x3x5, that’s 45 cubic feet, or about $70. The crate can, of course, be made smaller and consequently shipped cheaper by removing your bike’s wheels and handlebars. For the sake of comparison, Baigorria told us that the trucking charge from the West Coast to the East Coast is in the neighborhood of $100.

As for insurance, the shipping companies have their own—you pay no extra fee.

If you arrive in New York, the State Cooperage Export Co., 61 Wythe Ave., Brooklyn, is quite willing to crate your machine for shipping back West. Mr. Gross, who is the man to talk to there, estimated about $125 to make a box for a 750cc bike. Arrow-Lifschultz Freight Forwarders, a separate enterprise located at 386 Park Ave. South, New York City, will transport the crate from Brooklyn to your area, or for an extra charge of 5 to 10 percent, to your doorstep.

Arrow-Lifschultz rates, according to David Berman there, are $25.58 per 100 pounds. Berman figures seven days, crosscountry.

Rates sometimes vary, especially on crating. Shopping around is a good idea. Try it this way: If you’re ending your trip in Chicago, get a Chicago Yellow Pages from the phone company office before you leave home and find a freight handler who promises to do the job when you get there. This gives you peace of mind for the journey, and an address to head for. When you arrive, go through the phone book again, and collect a handful of quotes.

Shopping long distance by phone is too expensive since you’ll hit dead ends, and frequently be left on hold. But freighthandling is highly competitive, and once there, it won’t be hard to find the lowest bid. We saved $25 that way in San Francisco.

In any case, the trip that results from these arrangements is a bargain. Bikes get pretty good gasoline mileage, and biker’s expenses tend to be less destructive to the wallet than those of automobile or RV pilots. Maybe because cyclists tend to go to bed earlier.

Many riders carry camping gear and further cut the corners. To each his own. We stayed at motels, the flashiest we could find. Nothing like a gin and tonic at poolside to sooth away the Kansas crosswind. Our daily costs from New York to Arizona averaged $40, including lodging which cost between $14 and $22 a night.

It is indeed a big country, and seems even bigger by bike than by airplane or even a car. To descend at dawn into Monument Valley, Utah on a motorcycle and see no other person or vehicle for 50 miles in any direction, or to ride through a light rain in the lush hills of West Virginia, is what these big bikes were built for.

It’s also much easier to convince a lovely lady to come along if you can show her the plane ticket that will bring her home. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

February 1977 -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1977 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

February 1977 -

Technical

TechnicalTroubleshooting Carburetors: Rebuilding And Tuning Twins And Triples

February 1977 By Len Vucci -

Competition

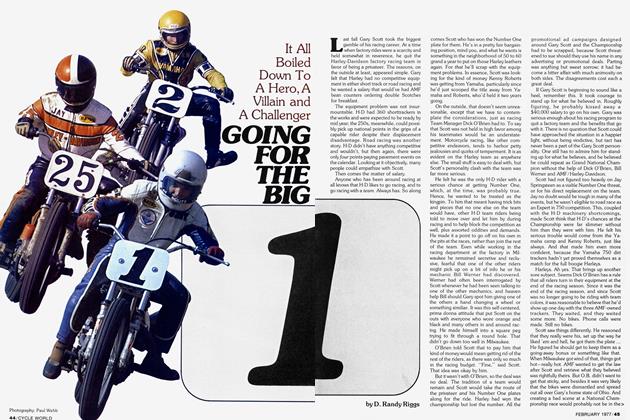

CompetitionGoing For the Big 1

February 1977 By D. Randy Riggs -

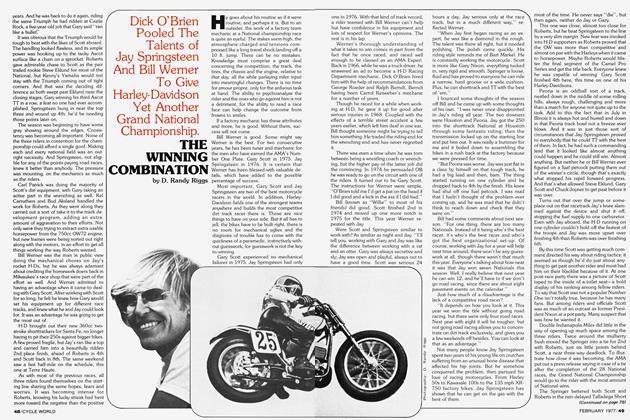

Competition

CompetitionThe Winning Combination

February 1977 By D. Randy Riggs