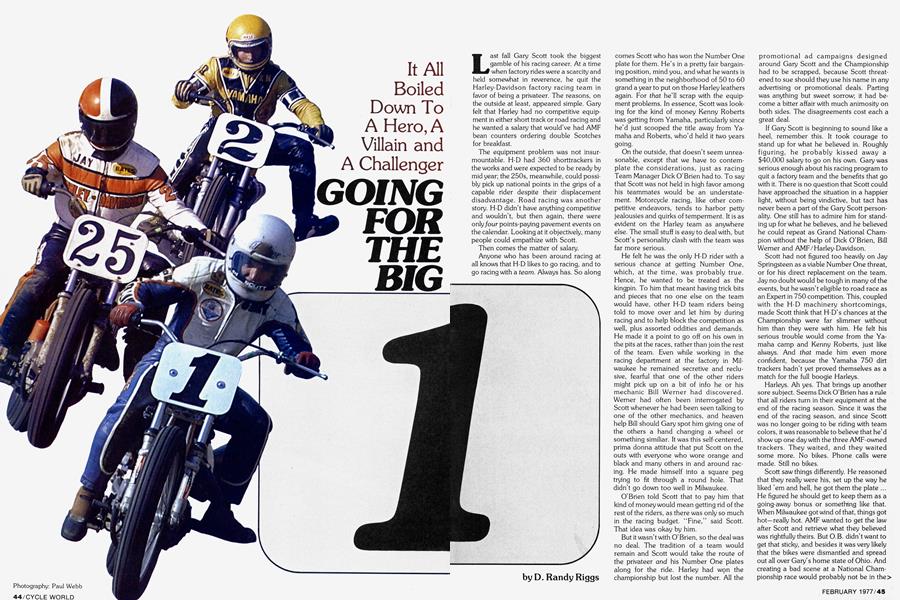

GOING FOR THE BIG 1

It All Boiled Down To A Hero, A Villain and A Challenger

D. Randy Riggs

Last fall Gary Scott took the biggest gamble of his racing career. At a time when factory rides were a scarcity and held somewhat in reverence, he quit the Harley-Davidson factory racing team in favor of being a privateer. The reasons, on the outside at least, appeared simple. Gary felt that Harley had no competitive equipment in either short track or road racing and he wanted a salary that would’ve had AMF bean counters ordering double Scotches for breakfast.

The equipment problem was not insurmountable. H-D had 360 shorttrackers in the works and were expected to be ready by mid year; the 250s, meanwhile, could possibly pick up national points in the grips of a capable rider despite their displacement disadvantage. Road racing was another story. H-D didn’t have anything competitive and wouldn’t, but then again, there were only four points-paying pavement events on the calendar. Looking at it objectively, many people could empathize with Scott.

Then comes the matter of salary. Anyone who has been around racing at all knows that H-D likes to go racing, and to go racing with a team. Always has. So along comes Scott who has won the Number One plate for them. He’s in a pretty fair bargaining position, mind you, and what he wants is something in the neighborhood of 50 to 60 grand a year to put on those Harley leathers again. For that he’ll scrap with the equipment problems. In essence, Scott was looking for the kind of money Kenny Roberts was getting from Yamaha, particularly since he’d just scooped the title away from Yamaha and Roberts, who’d held it two years going.

On the outside, that doesn’t seem unreasonable, except that we have to contemplate the considerations, just as racing Team Manager Dick O’Brien had to. To say that Scott was not held in high favor among his teammates would be an understatement. Motorcycle racing, like other competitive endeavors, tends to harbor petty jealousies and quirks of temperment. It is as evident on the Harley team as anywhere else. The small stuff is easy to deal with, but Scott’s personality clash with the team was far more serious.

He felt he was the only H-D rider with a serious chance at getting Number One, which, at the time, was probably true. Hence, he wanted to be treated as the kingpin. To him that meant having trick bits and pieces that no one else on the team would have, other H-D team riders being told to move over and let him by during racing and to help block the competition as well, plus assorted oddities and demands. He made it a point to go off on his own in the pits at the races, rather than join the rest of the team. Even while working in the racing department at the factory in Milwaukee he remained secretive and reclusive, fearful that one of the other riders might pick up on a bit of info he or his mechanic Bill Werner had discovered. Werner had often been interrogated by Scott whenever he had been seen talking to one of the other mechanics, and heaven help Bill should Gary spot him giving one of the others a hand changing a wheel or something similiar. It was this self-centered, prima donna attitude that put Scott on the outs with everyone who wore orange and black and many others in and around racing. He made himself into a square peg trying to fit through a round hole. That didn’t go down too well in Milwaukee.

O’Brien told Scott that to pay him that kind of money would mean getting rid of the rest of the riders, as there was only so much in the racing budget. “Fine,” said Scott. That idea was okay by him.

But it wasn’t with O’Brien, so the deal was no deal. The tradition of a team would remain and Scott would take the route of the privateer and his Number One plates along for the ride. Harley had wçn the championship but lost the number. All the promotional ad campaigns designed around Gary Scott and the Championship had to be scrapped, because Scott threatened to sue should they use his name in any advertising or promotional deals. Parting was anything but sweet sorrow; it had become a bitter affair with much animosity on both sides. The disagreements cost each a great deal.

If Gary Scott is beginning to sound like a heel, remember this. It took courage to stand up for what he believed in. Roughly figuring, he probably kissed away a $40,000 salary to go on his own. Gary was serious enough about his racing program to quit a factory team and the benefits that go with it. There is no question that Scott could have approached the situation in a happier light, without being vindictive, but tact has never been a part of the Gary Scott personality. One still has to admire him for standing up for what he believes, and he believed he could repeat as Grand National Champion without the help of Dick O’Brien, Bill Werner and AMF/Harley-Davidson.

Scott had not figured too heavily on Jay Springsteen as a viable Number One threat, or for his direct replacement on the team. Jay no doubt would be tough in many of the events, but he wasn’t eligible to road race as an Expert in 750 competition. This, coupled with the H-D machinery shortcomings, made Scott think that H-D’s chances at the Championship were far slimmer without him than they were with him. He felt his serious trouble would come from the Yamaha camp and Kenny Roberts, just like always. And that made him even more confident, because the Yamaha 750 dirt trackers hadn’t yet proved themselves as a match for the full boogie Harleys.

Harleys. Ah yes. That brings up another sore subject. Seems Dick O’Brien has a rule that all riders turn in their equipment at the end of the racing season. Since it was the end of the racing season, and since Scott was no longer going to be riding with team colors, it was reasonable to believe that he’d show up one day with the three AMF-owned trackers. They waited, and they waited some more. No bikes. Phone calls were made. Still no bikes.

Scott saw things differently. He reasoned that they really were his, set up the way he liked ’em and hell, he got them the plate ... He figured he should get to keep them as a going-away bonus or something like that. When Milwaukee got wind of that, things got hot—really hot. AMF wanted to get the law after Scott and retrieve what they believed was rightfully theirs. But O.B. didn’t want to get that sticky, and besides it was very likely that the bikes were dismantled and spread out all over Gary’s home state of Ohio. And creating a bad scene at a National Championship race would probably not be in the> best interests of the sport, so O.B. persuaded his superiors to drop the cause.

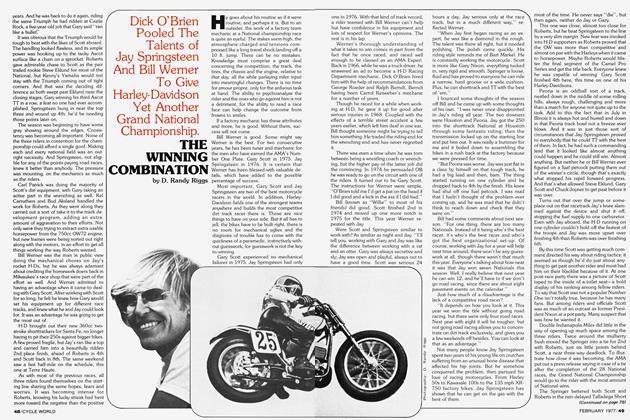

It is somewhat ironic that O. B. went to Bill Werner during the winter with the proposal that Werner work as Springer’s mechanic during the coming racing season. O.B. knew Bill was more than up to the task, buthe usually leaves the final decision up to the respective rider and mechanic. After all, the two have to work very closely during a long, hard schedule; the importance of a happy mix in personalities is all too apparent. After a short amount of thought, Werner and Springsteen became a team within a team, battling for more than just a championship . . . they went after the satisfaction of trouncing Gary Scott.

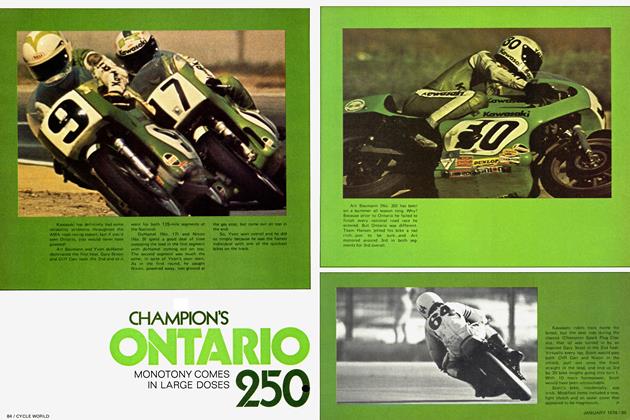

Houston always rolls around quicker than most would like. Suddenly as ever, the time had come. Roberts debuted all new equipment, Yamahas of course, with frames by C & J. Scott showed up with Harley and Yamaha 750 TT bikes and a 360 Yamaha for the Short Track. Springer, who had won two blistering half-mile Nationals as a rookie and propelled himself as high as 2nd in the National standings in 1975, showed off his new factory colors on a conventional-looking H-D 750 TT machine and one of the underpowered Italian-built 250 two-strokes for the roundy-round events.

There was little question even at the beginning of the season that the battle for Number One would be between these three riders. Kenny worried more about Jay than Gary and in fact, knowledgeable race observers drew many parallels between the riding styles of Jay and Kenny. Both can work around niggling little problems and stay on the gas, but Scott has more trouble dealing with things that are going against him.

In terms of proving anything, Houston was a wash, but the H-D camp derived much satisfaction when Springer made the National Short Track event on the bike Scott said wasn’t competitive. Gary didn’t, even riding the 360 Yamaha he said was competitive. On to Daytona. Scott again failed to score points when he crashed his Yamaha TZ-750 in practice, tearing up a hand as a reminder. So in the two types of events where Scott said he could do serious business without Team Orange and Black, the points tally said zero. Some of the teams were grinning ear to ear.

Four Nationals were held prior to the San Jose May Mile. Up to that point Springsteen had only one national point to show for his efforts. Scott wasn’t much better off with only 11 points, but didn’t have to miss any races with his injured hand because of the month lapse in the schedule between Daytona and Dallas. Roberts was the one with some cushion, 44 points worth.

San Jose’s May Mile is a pivotal point on the AMA calendar. It marks the first major dirt event of the year where horsepower and high speed talent come into play, a battleground rather than a recruit training depot. Riders are eager, mechanics curious about their latest creations, first year experts outwardly nervous. But it was time for all to do their stuff.

Yamaha, of course, had been working all winter on the OW72/750 project, in an effort to get a substantial amount of power out of the tracker engine for Kenny. And it looked like a threat until it expired on the line with electrical problems just before the National got underway. The Yamaha camp was bitterly disappointed, as Harley-Davidson went on to sweep the top three places, Springsteen in 2nd with Gary Scott 3rd.

There was to be even more drama after the event was over. Scott claimed Rex Beauchamp’s winning engine in a classic display of ballsy nerve, tweaking Dick O’Brien to near fury. It wasn’t the loss of the engine so much, it was losing the thing to someone who already had three others just like it. Unbelievable, they said . . . simply inconceivable. And yet, big as life, it had happened.

In the next six races, Roberts experienced every kind of trouble or heartbreak; teething problems with the OW, a controversial disqualification in the Pontiac TT and at Louden a crash caused by another rider when Kenny was in the lead. Scott and Springsteen, on the other hand, were quite consistent and added up national points as they went along. Both had problems in the Pontiac Short Track National, though, and Jay wasn’t eligible to ride the Open GP class at Louden.

By the end of June the three had scrambled themselves into the leading omelet of the Camel Pro Series; Springsteen and Scott tied in a knot at 95 points each while Kenny sat 12 behind, with 83. Jay’s additional experience on tracks around the nation was beginning to show. His win on the rutted, dusty Albuquerque Mile followed his victory on the Columbus Half-Mile the previous weekend. Springer thus became the first double winner on the National trail all year. More were coming for the likeable teenager, undaunted by his success and racing “for the fun of it”.

The Bill Werner/Gary Scott feud erupted early in the season, beginning with a disagreement about the ownership of some tools and equipment. Bill elected not to associate with Gary if he could help it. Gary took the brush-off to heart, and little by little, feelings grew hostile. The relationship took a complete dive at Albuquerque, when Scott, dicing for the lead in a heat race with H-D team rider Corky Keener, got off spectacularly in a high speed crash.

Werner, who was in the pits at the time, heard the crowd roar and jumped up on the fence to see what had happened. The race had been red flagged, and when Corky came around on the cool off lap Werner spotted him and was glad to see that he was okay, not even knowing at that point that Scott was the one that had gotten off. Someone in the pits saw Werner smiling and spread the word to the Scott pit that Werner had cheered when Gary crashed. It came as a surprise to Werner later, when Hank Scott came roaring up and said that he’d run Bill over if he ever did that again. Bill, now angry himself over what was occurring, saw that it was a fruitless effort to try to explain himself out of the situation. The chemistry was volatile; it was bound to explode before the season was over.

The Camel Pro Series payoff for the top 10 riders is divided into two legs with an overall payoff at the end of the season. The first leg was scheduled to end on the West Coast after yet another San Jose Fairgrounds event, this time a lightning quick nighttime half-mile, a new race on the calendar. With a strong finish here* Jay could sew up the $5000 1st place money for Leg 1, grab the point lead and head to the Northwest with a smile. But it wasn’t in the cards.

Though Jay qualified fastest and set a new San Jose lap record in the process, he perhaps tried too hard, too soon on the slick track surface. Going into Lap 2 of the National he got out of shape and slid the bike down and into the bales. The exhaust pipes were knocked loose from the header flange and by the time he got under way again, he was in last place, his point lead was lost and the $5000 1st place Camel money was out of reach.

But up front a new version of an old battle was underway, an epic Scott/Roberts duel. Gary led Kenny for a good portion of the event, with Roberts seemingly too far behind to overtake. But by experimenting with different lines, Kenny found his advantage, and on Lap 17 moved past Scott, taking a win that had the effect of a shot in the arm for Team Yamaha. The OW72 had won its first race, putting Roberts and Springsteen into a tie for 2nd in the standings, with Gary Scott six points in the lead. It was a mere hint of the battles to follow, and people were beginning to wonder out loud if indeed the championship would go down to the wire in the final race of the year at Ascot.

Roberts was not all that happy about the results of the next three Nationals. At the Castle Rock TT, a fork leg broke in half after an easy spill, putting him on the sidelines and into 14th place . . . for one mere national point. Scott resurrected an old Triumph and surprised the troops by finishing 7th, while Springsteen garnered 11th. As usual, Northwestern TT specialists dominated the event, but it failed to prove anything dramatic, though Scott’s point lead was stretched slightly.

Laguna Seca proved to be an up for Scott and somewhat of a down for Roberts. In the third road race of the year it was obvious that Gary was beginning to get more used to his Yamaha TZ-750 and was dealing well with the competition. Of course, it marked an opportunity for both him and Kenny to gain needed ground on Springsteen, who was not licensed for Expert 750 pavement scratching.

Scott tenaciously fought his way to a 4th overall while Roberts dealt with a brilliant Steve Baker, whom King Kenny himself couldn’t keep in sight. Second place paid valuable points, but Scott’s strong score served to nullify Roberts’ gain. Gary seemed to get tougher as the season wore on, his seriousness nearly rolling off him in droplets. No one showed more determination or drive and it was highly possible that Gary Scott would be the first non-factory rider to win the Grand National title since Dick Mann did it in 1963.

“My best races are coming.” That’s what Kenny Roberts was telling people when they asked him about his chances of grabbing back the big plate. And the Ascot TT would fall under that heading, though it was Scott who had won the event the two previous> years. And he was back to do it again, riding the same Triumph he had ridden at Castle Rock, a five-year-old job that Gary said “ran like a bullet’.’

It was obvious that the Triumph would be tough to beat with the likes of Scott aboard. The handling looked flawless, and its ample power was hooking up to the tacky Ascot surface like a chain on a sprocket. Roberts gave admirable chase to Scott as the pair trailed rookie Steve Eklund for most of the National, but Kenny’s Yamaha would not stay with the Triumph coming out of tight corners. And that was the deciding difference as both swept past Eklund near the closing stages, Gary winning his third Ascot TT in a row, a feat no one had ever accomplished. Springsteen hung in near the top three and wound up 4th; he’d be needing those points later on.

The season was beginning to have some grey showing around the edges. Consistency was becoming all-important. None of the three riders in contention for the championship could afford a single goof. Making each and every national field was an outright necessity. And Springsteen, not eligible for any of the points-paying road races, knew it better than anybody. The pressure was mounting, on the mechanics as much as the riders.

Carl Patrick was doing the majority of Scott’s dirt equipment, with Gary taking an active part in the wrenching as well. Kel Carruthers and Bud Aksland handled the work for Roberts. As they went along they carried out a sort of take-it-to-the-track development program, adding an extra amount of aggravation to their efforts. Not only were they trying to extract extra usable horsepower from the 750cc OW72 engine, but new frames were being sorted out right along with the motors, in an effort to get all things working the way Roberts wanted.

Bill Werner was the man in public view doing the mechanical chores on Jay’s rocket H-Ds, but he was always adamant about crediting the homework doers back in Milwaukee’s race shop that were part of the effort as well. And Werner admitted to having an advantage when it came to dealing with Gary Scott. After working with Scott for so long, he felt he knew how Gary would set his equipment up for different race tracks, and knew what he and Jay could look for. It was an advantage he was going to get the most out of.

H-D brought out their new 360cc twostroke shorttrackers for Santa Fe, no longer having to pit their 250s against bigger bikes. A few proved fragile, but Jay’s ran like a top and carried him into a beautifully ridden 2nd place finish, ahead of Roberts in 4th and Scott back in 8th. The same weekend saw a fast half-mile on the schedule, this one at Terre Haute.

As with most of the previous races, all three riders found themselves on the starting line sharing the same hopes, fears and worries. It was becoming intense for Roberts, knowing his lucky streak had bent more toward the negative than the positive most of the time. He never says “die”, but then again, neither do Jay or Gary.

This one was close, almost too close for Roberts, but he beat Springsteen to the line by a very slim margin. New fear was invoked into H-D supporters as Roberts proved that the OW was more than competitive and almost on par with the Harleys when it came to horsepower. Maybe Roberts would blister the final segment of the Camel Pro Series and get the title back. Everyone knew he was capable of winning. Gary Scott finished 4th here, this time on one of his Harley-Davidsons.

Peoria is an oddball sort of a track, nestled down in the middle of some rolling hills, always rough, challenging and more than a match for anyone not quite up to the task. Add to this the fact that in July in Illinois it is always hot and humid and down in that Peoria track bowl not a breeze ever blows. And it was in just those sort of circumstances that Jay Springsteen proved to everybody that he could TT with the best of them. In fact, he had such a commanding lead that it looked like almost anything could happen and he could still win. Almost anything. But neither he or Bill Werner ever figured on a fuel petcock putting them out of the winner’s circle, though that’s exactly what stopped his rapid forward progress. And that’s what allowed Steve Eklund, Gary Scott and Chuck Joyner to get past before it was over.

Turns out that over the jump or someplace out on that racetrack Jay’s knee slammed against the device and shut it off, stopping the fuel supply to one carburetor. Even with Jay aboard, the H-D running on one cylinder couldn’t hold off the fastest of the troops and Jay was more upset over finishing 4th than Roberts was over finishing 6th.

By this time Scott was getting much comment directed his way about riding tactics; it seemed as though he’d do just about anything to get past another rider and most had him on their blacklist because of it. At one post-race party there was a picture of Scott taped to the inside of a toilet seat—a bold display of his ranking among fellow riders. To say that Scott was not a popular Number One isn’t totally true, because he has many fans. But among riders and officials Scott was as much of an outcast as former President Nixon at a pot party. Many suspect that was how he wanted it.

Double Indianapolis Miles did little in the way of opening up much space among the three riders. Twice around the mulberry bush moved the Springer into a tie for 2nd with Roberts, just six little points behind Scott, a near three-way deadlock. To illustrate how close it was becoming, the AMA put out a press release saying in case of a tie after the completion of the 28 National races, the Grand National Championship would go to the rider with the most amount of National wins.

The Springer bettered both Scott and Roberts in the rain-delayed Talladega Short Track by finishing 4th. But Werner said later that he probably would have done better yet if the race hadn’t been stopped, allowing some of the competition to see Jay’s tire combination, which they copied. Scott ran 7th and Roberts a terrible 12th, off of his usual blistering short track pace.

(Continued on page 78)

Continued from page 49

Kenny did come back the following weekend with things going more his way. It was the gritty Syracuse Mile and the Yamaha OW72 was running right with the fastest Harleys. Roberts came close to winning, but made a mistake late in the shortened race which cost him ground that couldn’t be made up in the time remaining. Jay won his fourth of the year by an inch over Rex Beauchamp, taking over the point lead in the process. Scott finished back in 6th, and, angry over his defeat, filed an official protest against Roberts for rough riding.

Everyone considered that about the funniest thing they’d heard all year, a classic case of the pot calling the kettle black. AMA officials dismissed it on the spot, but Gary insisted that Roberts was “flicking it sideways” and into his front wheel. Kenny said, “Heck, Gary, you oughta learn to flick it sideways too, maybe you’d go faster!”

Toledo’s narrow groove half-mile was expected to be friendly turf for Roberts, but the Harleys would be just as dangerous on the slick surface. Kenny proved to be off key most of the day, however, and his mistakes proved costly. Everyone knew he was capable of finishing higher than 9th. Springsteen notched win number five and did it in a wireto-wire runaway, as if he were Mickey Mantle and the others were minor leaguers.

Scott finished in the number two spot, after his brother Hank let him by on the last lap to give a family boost in the title chase. It gave Gary three extra points to take to the West Coast; just three races remained, one of which Jay Springsteen was not eligible to compete in.

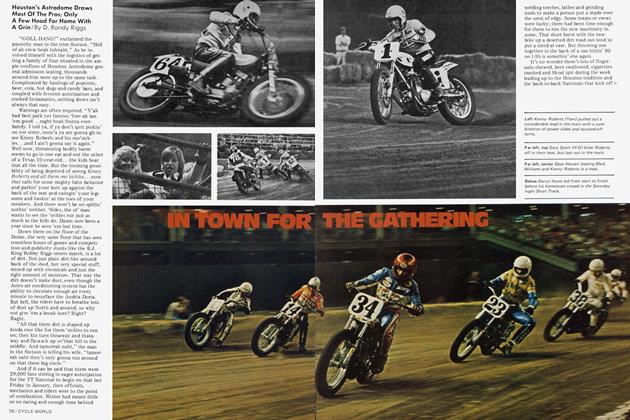

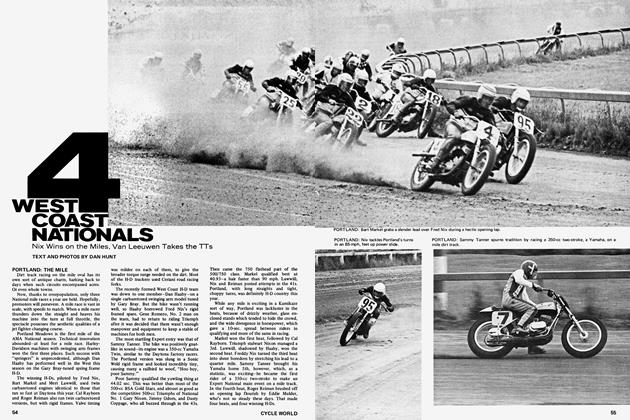

Skies over the famous San Jose Mile remained gray all race day, allowing a consistent and fast track surface. And in typical San Jose fashion, a car cover could fit over the leading group of riders, tightly bunched, handlebar rubbing handlebar at 130 mph.

Roberts was virtually in a must-win situation to keep his title hopes alive; Jay and Gary could afford nothing less than winner’s circle points.

Jay’s test came when Gene Romero spilled and the fallen machine came to rest in his path. Over a wheel Jay went, remaining upright but losing several positions. Back on the gas he went, passing the competition one by one, arriving behind Gary Scott, then waving as he skidded past, onward to win number six. That put him 16 ahead of Scott and 39 in front of Roberts who wound up 5th. The decider then, would be Ascot’s dangerously fast half-mile, and what remained for Scott and Roberts was to garner as many points as possible at the Riverside road race.

But the drama of San Jose was not quite over. Bill Werner understandably was rubbing in Jay’s win to Scott, Scott not appreciating one bit of it. When Werner adjourned a post-race party in favor of a local pub, Gary and his brother Hank followed.

Once in the bar, Bill was not crazy about the vibes radiating off the Scott brothers, so decided to hit the john and the road, in that order. The next thing he knew he was being pounded from what seemed like all sides. Scott had jumped him from behind. By the time Werner had recovered his senses and had his former rider and friend in a headlock, the bouncers jumped in and probably saved Scott from a severe licking.

Six stitches in Werner’s lip were evidence to Gary’s buildup of pressure and frustration. Scott had simply had enough of the teasing and brush-offs and took it out on the guy who was getting to him the most. Werner said, “That was no fight, I was just plain attacked.” And Scott said, “I knew Werner was a wrestler and he’s bigger than me, so I knew I had to get in one or two good ones before he knew what was happening. Anyway, I think we’re even now, I have some pretty good bruises myself. I’m just not gonna take anything from anybody. They keep calling me a bad guy so guess I’m gonna have to act like one.”

Team Manager Dick O’Brien was worried. “I just hope they keep things settled down until after everything is over. It would be bad for someone to get hurt now and have the championship be decided in a fistfight.”

Perhaps it was karma that caught up with Scott at Riverside, where he had a good chance of earning enough points to pressure Jay right out of the plate. Gary had himself a good Yamaha road racer, and in theory could run close to the leaders, a definite contender for the top five.

Sometimes things don’t quite go according to plan. When Scott’s heat race was called to the line, there was no bike sporting Number One and no Gary Scott. He arrived at the line on foot and his bike was brought out by another rider. In his haste, Gary jumped on and promptly fell over, much to the amusement of the crowd. He started two laps down and never caught up and was forced to start on the last row in the last starting wave of the National, with scores of riders ahead of him.

By the race’s end he had worked into 11th spot (Roberts was the winner) but he certainly would’ve finished much higher if it weren’t for the goof. His mechanics claimed the announcement for the grid call wasn’t heard because of poor loudspeakers, but since all the other riders in the same garage heard the call, and since the time was printed in the program, there could be little in the way of excuses for missing the start. Werner said, “Knowing Gary, he probably had them change some stupid thing at the very last minute and they couldn’t get it done in time. He used to do that to me a lot.”

And so it would be Ascot. Mathematically, Springsteen, Scott or Roberts could do it. Roberts was the underdog, since he needed almost the impossible to grab the championship. Both Scott and the Springer would have to be beaten or break in the heats and not transferto the National. Roberts, in the meantime, would have to win Ascot. Pretty impossible odds.

All Springsteen had to do was finish 7th or better. Scott needed a 3rd and some bad luck for Jay.

Ironically, the promised thriller was nearly over before it began. Practicing with teammate Rex Beauchamp in the late afternoon sun, Jay found it impossible to avoid Beauchamp when Rex got sideways coming off of Ascot's south turn. Springer clipped him at over 75 mph. Beauchamp tweaked his knee, but Springsteen was stunned, seeing double and nursing a dislocated finger, after the heart-stopping crash.

Werner, who’d seen many a dislocated finger in his wrestling days, just “yanked it back in place”. The Springer had a little while to rest before he made an attempt at qualifying, and was eventually one of the last to do so, ticking in at 8th fastest. As fate would have it, the time put Jay right next to Scott in the same heat race. One observer cracked, “Boy, all Scott has to do now is knock him off and the plate is his.” Only he had to catch Jay first.

Side by just for a second or two in the first turn, one knew that Scott just might try anything. But Jay motored away quite handily, sore hand and all, on a track that was supposed to be a nemesis for out-of-staters. And Jay’s heat race victory trashed the hopes of Roberts, who found himself fighting his way into the National with a do-or-die win in the Semi.

Instructions from the H-D camp were simple. Jay was told to ride his own race, to be comfortable, to not take chances. Grabbing the lead at the start, he immediately set up a duel with Ascot regular Alex Jorgensen, who managed to pass Jay on Lap 15. But Jay came right back, swooped by Jorgy, gave the H-D gang terminal heart failures while he risked everything, literally, by dicing for the lead, got command of the situation and won the race of his life.

It was inconceivable for the outcome of 28 thunderous, non-forgiving championship races to be decided with the swiftness of a guillotine in one final event, and yet, it happened.

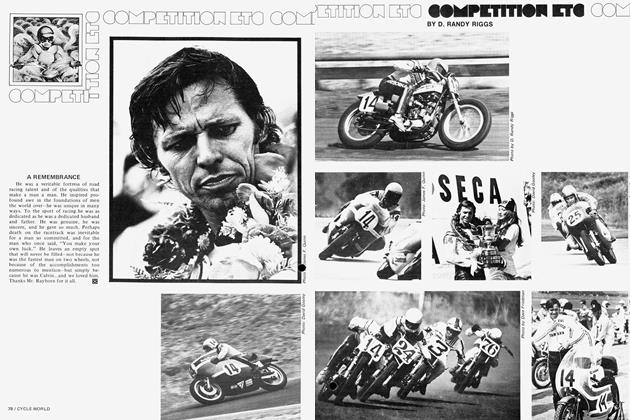

Ascot proved to be the cockfight of the season and Jay Springsteen was the rooster that went away crowing I~I

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

February 1977 -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1977 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

February 1977 -

Technical

TechnicalTroubleshooting Carburetors: Rebuilding And Tuning Twins And Triples

February 1977 By Len Vucci -

Competition

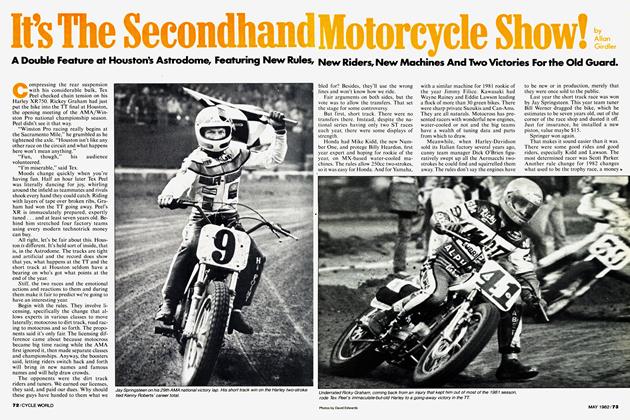

CompetitionThe Winning Combination

February 1977 By D. Randy Riggs -

Features

FeaturesAn Off-Color Guide To Daytona Speed Week

February 1977 By D. Randy Riggs