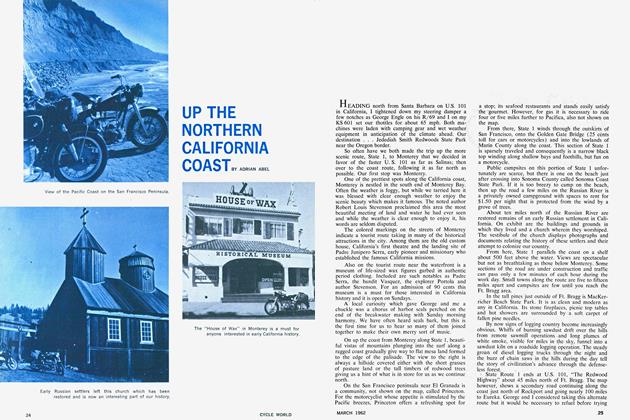

To Mexico The de Anza Trail

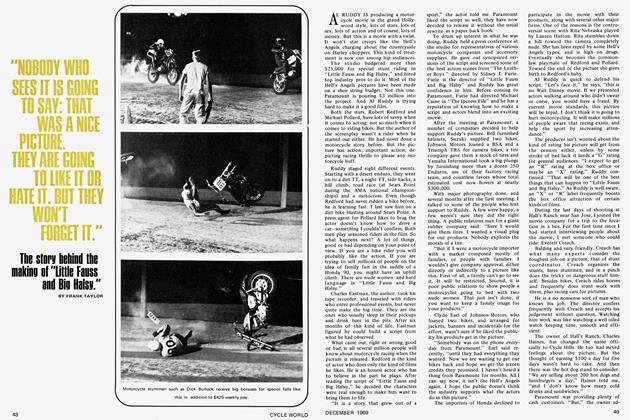

Yamaha 80s on the Highway of Death

FRANK TAYLOR

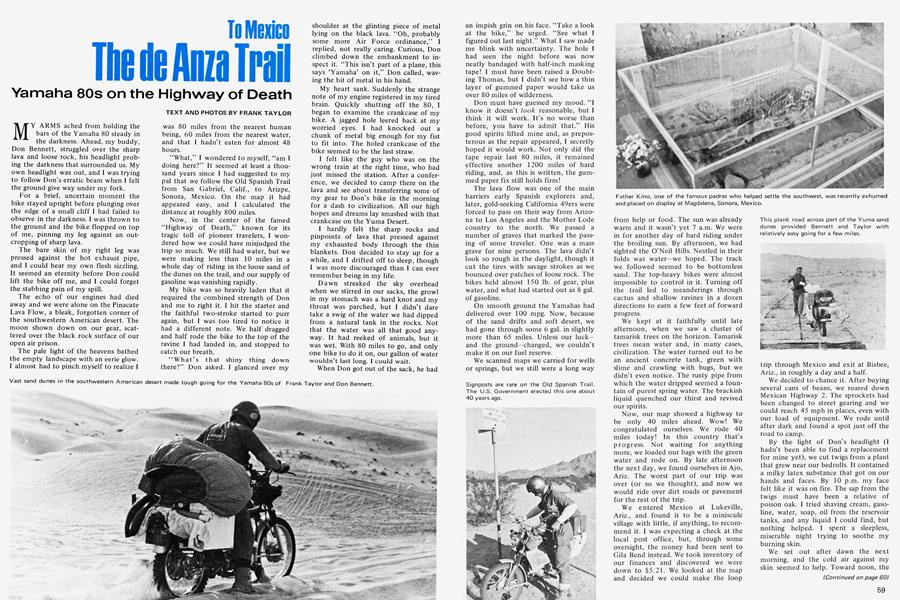

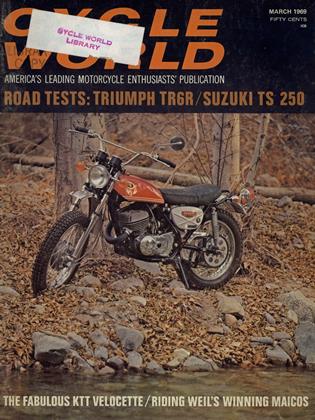

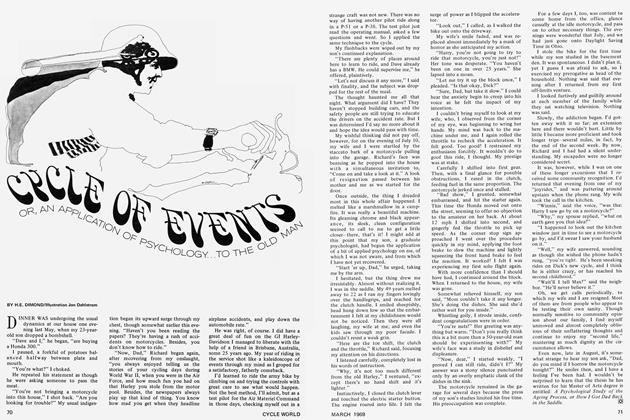

MY ARMS ached from holding the bars of the Yamaha 80 steady in the darkness. Ahead, my buddy, Don Bennett, struggled over the sharp lava and loose rock, his headlight probing the darkness that surrounded us. My own headlight was out, and I was trying to follow Don’s erratic beam when I felt the ground give way under my fork.

For a brief, uncertain moment the bike stayed upright before plunging over the edge of a small cliff I had failed to observe in the darkness. I was thrown to the ground and the bike flopped on top of me, pinning my leg against an outcropping of sharp lava.

The bare skin of my right leg was pressed against the hot exhaust pipe, and I could hear my own flesh sizzling. It seemed an eternity before Don could lift the bike off me, and I could forget the stabbing pain of my spill.

The echo of our engines had died away and we were alone on the Pinacate Lava Flow, a bleak, forgotten corner of the southwestern American desert. The moon shown down on our gear, scattered over the black rock surface of our open air prison.

The pale light of the heavens bathed the empty landscape with an eerie glow. I almost had to pinch myself to realize I was 80 miles from the nearest human being, 60 miles from the nearest water, and that I hadn’t eaten for almost 48 hours.

“What,” I wondered to myself, “am I doing here?” -It seemed at least a thousand years since I had suggested to my pal that we follow the Old Spanish Trail from San Gabriel, Calif., to Arizpe, Sonora, Mexico. On the map it had appeared easy, and I calculated the distance at roughly 800 miles.

Now, in the center of the famed “Highway of Death,” known for its tragic toll of pioneer travelers, I wondered how we could have misjudged the trip so much. We still had water, but we were making less than 10 miles in a whole day of riding in the loose sand of the dunes on the trail, and our supply of gasoline was vanishing rapidly.

My bike was so heavily laden that it required the combined strength of Don and me to right it. I hit the starter and the faithful two-stroke started to purr again, but I was too tired to notice it had a different note. We half dragged and half rode the bike to the top of the ravine I had landed in, and stopped to catch our breath.

“What’s that shiny thing down there?” Don asked. I glanced over my shoulder at the glinting piece of metal lying on the black lava. “Oh, probably some more Air Force ordinance,” I replied, not really caring. Curious, Don climbed down the embankment to inspect it. “This isn’t part of a plane, this says ‘Yamaha’ on it,” Don called, waving the bit of metal in his hand.

My heart sank. Suddenly the strange note of my engine registered in my tired brain. Quickly shutting off the 80, I began to examine the crankcase of my bike. A jagged hole leered back at my worried eyes. I had knocked out a chunk of metal big enough for my fist to fit into. The holed crankcase of the bike seemed to be the last straw.

I felt like the guy who was on the wrong train at the right time, who had just missed the station. After a conference, we decided to camp there on the lava and see about transferring some of my gear to Don’s bike in the morning for a dash to civilization. All our high hopes and dreams lay smashed with that crankcase on the Yuma Desert.

I hardly felt the sharp rocks and pinpoints of lava that pressed against my exhausted body through the thin blankets. Don decided to stay up for a while, and I drifted off to sleep, though I was more discouraged than I can ever remember being in my life.

Dawn streaked the sky overhead when we stirred in our sacks, the growl in my stomach was a hard knot and my throat was parched, but I didn’t dare take a swig of the water we had dipped from a natural tank in the rocks. Not that the water was all that good anyway. It had reeked of animals, but it was wet. With 80 miles to go, and only one bike to do it on, our gallon of water wouldn’t last long. I could wait.

When Don got out of the sack, he had an impish grin on his face. “Take a look at the bike,” he urged. “See what I figured out last night.” What I saw made me blink with uncertainty. The hole I had seen the night before was now neatly bandaged with half-inch masking tape! I must have been raised a Doubting Thomas, but I didn’t see how a thin layer of gummed paper would take us over 80 miles of wilderness.

Don must have guessed my mood. “I know it doesn’t look reasonable, but I think it will work. It’s no worse than before, you have to admit that.” His good spirits lifted mine and, as preposterous as the repair appeared, I secretly hoped it would work. Not only did the tape repair last 80 miles, it remained effective another 1200 miles of hard riding, and, as this is written, the gummed paper fix still holds firm!

The lava flow was one of the main barriers early Spanish explorers and, later, gold-seeking California 49ers were forced to pass on their way from Arizona to Los Angeles and the Mother Lode country to the north. We passed a number of graves that marked the passing of some traveler. One was a mass grave for nine persons. The lava didn’t look so rough in the daylight, though it cut the tires with savage strokes as we bounced over patches of loose rock. The bikes held almost 150 lb. of gear, plus water, and what had started out as 8 gal. of gasoline.

On smooth ground the Yamahas had delivered over 100 mpg. Now, because of the sand drifts and soft desert, we had gone through some 6 gal. in slightly more than 65 miles. Unless our luck— and the ground—changed, we couldn’t make it on our fuel reserve.

We scanned maps we carried for wells or springs, but we still were a long way from help or food. The sun was already warm and it wasn’t yet 7 a.m. We were in for another day of hard riding under the broiling sun. By afternoon, we had sighted the O’Neil Hills. Nestled in their folds was water—we hoped. The track we followed seemed to be bottomless sand. The top-heavy bikes were almost impossible to control in it. Turning off the trail led to meanderings through cactus and shallow ravines in a dozen directions to earn a few feet of forward progress.

We kept at it faithfully until late afternoon, when we saw a cluster of tamarisk trees on the horizon. Tamarisk trees mean water and, in many cases, civilization. The water turned out to be an ancient concrete tank, green with slime and crawling with bugs, but we didn’t even notice. The rusty pipe from which the water dripped seemed a fountain of purest spring water. The brackish liquid quenched our thirst and revived our spirits.

Now, our map showed a highway to be only 40 miles ahead. Wow! We congratulated ourselves. We rode 40 miles today! In this country that’s progress. Not waiting for anything more, we loaded our bags with the green water and rode on. By late afternoon the next day, we found ourselves in Ajo, Ariz. The worst part of our trip was over (or so we thought), and now we would ride over dirt roads or pavement for the rest of the trip.

We entered Mexico at Lukeville, Ariz., and found it to be a miniscule village with little, if anything, to recommend it. I was expecting a check at the local post office, but, through some oversight, the money had been sent to Gila Bend instead. We took inventory of our finances and discovered we were down to $5.21. We looked at the map and decided we could make the loop trip through Mexico and exit at Bisbee, Ariz., in roughly a day and a half.

We decided to chance it. After buying several cans of beans, we roared down Mexican Highway 2. The sprockets had been changed to street gearing and we could reach 45 mph in places, even with our load of equipment. We rode until after dark and found a spot just off the road to camp.

By the light of Don’s headlight (I hadn’t been able to find a replacement for mine yet), we cut twigs from a plant that grew near our bedrolls. It contained a milky latex substance that got on our hands and faces. By 10 p.m. my face felt like it was on fire. The sap from the twigs must have been a relative of poison oak. I tried shaving cream, gasoline, water, soap, oil from the reservoir tanks, and any liquid I could find, but nothing helped. I spent a sleepless, miserable night trying to soothe my burning skin.

We set out after dawn the next morning, and the cold air against my skin seemed to help. Toward noon, the warm sun and hum of my engine made me drowsy, and suddenly I caught the Yamaha at the last instant before it flopped—I had dozed off, and had nearly taken a spill in the middle of the highway. This helped to keep me awake for the rest of the day.

(Continued on page 60)

Continued from page 59

Our first major stop was Caborca. There is a magnificent old mission here that had been a stopping place for Spanish travelers on the trail to California, and we wanted to see it. We had a hard time getting people to understand what we wanted, so we rode to the police station.

The only thing the first policeman could say in English was, “Papers?” He was packing the biggest revolver I have ever seen. When anybody shoves a gun like that at me, Em ready to show him every piece of paper I own. We even fished out a roll of toilet paper—just in case.

Eventually we located a fellow who could direct us to the church, and we made the pilgrimage. The mission at Caborca was once the focal point of one of the Mexican revolutions and boasts real cannonball holes and bullet pockmarks. We shot quite a bit of film for the people at home, and were ready to leave when an old Mexican offered to show us the inside of the church. It was a magnificent sight.

The towering walls seemed to vanish in the dim light overhead. A huge dome encloses the main part of the building, and tiny windows permit light to pour inside the building in long shafts. The air was cool and still, quite a contrast to the heat of the day outside.

We continued south on Highway 2 until we reached the junction of Highway 15. We turned north again and rode to the old town of Magdalena. Here another old church stands in the Mexican sunshine, exactly as it has for centuries.

Across the street, the ruin of a still earlier church is preserved by a roof. Here lie the bones of the famous Father Kino, an Italian priest who established a chain of missions throughout Mexico and Arizona. The padre’s bones lie in full view inside a glass case. A number

of other individual’s bones also are on display at the same place.

We planned to reach Cananea that night, but we got a slow start and darkness found us on the high mountains, in quickly lowering temperatures. We put on all our extra clothing, and tried to ride on, but the thermometer had dropped to 20 F, and was still falling by 9 p.m.

There was almost no place to turn off the twisting mountain road, so we wound up about 10 ft. from the pavement in a shallow ditch. This was a mistake we found out later that night. Every car driver saw our bikes'and gear and stopped for a closer look. Many of them backed up and turned their headlights on us. At least one murmured, “Crazy gringos!” when he was satisfied we were just sleeping and hadn’t had an accident.

We saw the smokestacks of Cananea, and their belching clouds of vapor, long before the famous mining town came into view. The town is headquarters for a large open pit copper mine and is quite modern by Mexican standards. We panted to travel south to Arizpe, about 80 miles down river from Cananea. The kibitzers at the local service station all wanted to give us directions at once—in Spanish, of course. When we were ready to give up, a skinny fellow came up and spoke to us in English. He seemed to know what he was talking about, and we took his directions.

The road led out of town to a bumpy track that threaded its way toward the horizon in a lazy fashion, following lines of least resistance. We had hardly set out when a bus came beeping behind us, scattering rocks and chickens in its path.

We ducked to the side and the driver stopped to chat. He offered to take us and the bikes to Arizpe, riding the top of his rickety bus. We declined and he shrugged his shoulders. With a crash of gears, he lurched off down the steep, winding track, skidding on two wheels. We congratulated ourselves on a wise decision.

At the bottom of the first grade, we saw something that stopped us in our tracks. A small river about 20 ft. across was pouring under a wooden bridge. The only thing different about this river was the color. It was Navy gray and, instead of water, it was liquid mud. We learned this was pollution caused by copper mining. The mine dumped so much tailings into the river it was turned to an awful, brackish muck.

We started to cross the river several times and, after the first impromptu bath, we ceased to worry about getting wet every 10 min. or so. At one point, we climbed out of the river bottom and found a fairly smooth road. I decided to make some time and took off at about 35 mph. Rounding a bend, too late I saw the smooth dirt ended—zap! I hit a series of big dips and loose gravel. The bike flew into the air and came down with a thud. We both rolled over. For a while I was on top, then the Yamaha was. When the dust settled, I had skidded 35 or 40 ft. and gear was strung from one side of the road to the other.

Don had a good laugh, and we picked everything up and started off again. Less than 15 min. later, Don did the same thing. But he scraped enough hide off to pave a small parking lot. Worse yet, one of the braces that held his wooden cargo box in place broke, allowing the box to hit the chain. We tied and fiddled until we got the box off the chain and kept on riding.

At sundown we were in a series of fords and small river bottom valleys, but no Arizpe was in sight. We had stopped at a stream to eat a can of beans when a truck pulled up. The passenger was a local doctor and he said we were on the worst road in Mexico. No wonder it took so long to get from place to place!

(Continued on page 65)

Continued from page 60

“But,” he said with a broad grin, “you are only two hours travel from Arizpe!” This cheered us up a bit, and we told him we would follow him to town. He took off like a bolt of lightning and we brought up the rear, choking on the dust cloud his wheels created. Less than 5 miles of this was under our belts when Don discovered our spare gasoline can was gone. Going back to recover it took most of an hour, because it was getting dark and the “road” was nothing more than bare rock—no dirt, just a big rock face going straight up, or so it seemed.

We rode until 8 p.m. and decided to call it quits when a Mexican we met in the dark told us Arizpe was only two hours ahead. “At least we are gaining on it,” Don mumbled as he helped me make camp. That night, he took part of a parachute we had found near the Highway of Death and bound up the break on his brace. After tying everything off, he covered the lump with epoxy glue. I had my doubts about the permanency of his repair, but, after the job his masking tape had done on my crankcase, I wasn’t about to question him.

The next morning, about 10 a.m., we rolled into Arizpe. It was Saturday and the children attended school half a day. The school was across from the church, where the bones of Don Juan Batista de Anza were on display, and we were mobbed with kids who were fascinated with our bikes. Leaving the bikes in the charge of one youngster, we went inside to pay our respects to the famed Spanish explorer who had been responsible for finding the first land route to California.

According to an English-speaking fellow we met, the church had been built in 1633 and had been in constant use ever since. Like the church at Caborca, the ceiling was very high, but this one was in restored condition. The homemade coffin of de Anza lay in a special recessed chamber in the floor. The top of this was covered with a plate of glass.

The full skeleton of de Anza could be seen, along with bits of his military uniform. He had been resting in the church since his death in 1788. Now, almost 193 years later, my friend and I had successfully retraced his footsteps by motorcycle, and now stood by his side.

We wanted to stay longer in Arizpe, but with only one can of beans between us and the border, and less than 20 pesos in our pockets (about $1.50), we decided to head north. We bid goodby to our new friends and, getting some directions, we headed out of town on the “good” road. This led down the river, and we found ourselves plowing in deep sand and fording the river from side to side.

We left Arizpe at 2 p.m. By dark, we were still in the riverbottom, crossing streams. By this time, however, a wind had come up and the water felt icy in our boots. The engines had been submerged completely in several deep places, but once we dried off the ignition wire to the plug, they would kick off like troopers.

Our bedrolls were wet clear through from the splashing water, and both of us were wet to the hips. Riding like this at high elevation made us ever more miserable. Eventually, the road wound upward, out of the riverbottom, but not before we had crossed the stream 44 times!

We were so cold it was a job even to hang onto the bars. Yet, with wet bedrolls, we had no place to turn. We saw a light and decided to ask the owners of the ranch for shelter. After introducing ourselves to the lady of the house, who turned out to be an American now living in Mexico, we were invited in.

After a hearty meal of tamales and refried beans, our hostess invited us to sleep on her concrete porch. We had dried our bedrolls next to the ranch fireplace, and the hard floor felt like heaven. That night, the temperature hit 10 F, but we slept snug in our bags. It was only 30 F on the porch.

The next morning we discovered our hosts had a tequila factory. We were invited to fill our canteens, but we don’t drink, so we reluctantly passed up the invitation. Our host, the Hector Salazar family, gave us a hot breakfast and enough gasoline to fill our tanks before saying goodby. We were now only three hours from Cananea, and six hours from the border.

We rolled across the United States border at dusk and were happy to see American soil again, though this looked just like ordinary Mexican dirt. We rode across the desert from Bisbee to Nogales, then from Nogales to Lukeville again. From there we turned north to Gila Bend and followed Highway 8 to Yuma.

At Yuma, we had a little time, so we visited the Yuma Territorial Prison. It was a spooky experience to wander through the black dungeons and cells of this former “Hell Hole” of the Southwest. We had ridden across the sand dunes and through the open spaces of the Borrego Desert on our way south, but now we stuck to paved roads.

On Nov. 13, we rolled past the venerable remains of Mission San Gabriel at San Gabriel, Calif. Our odometers registered just under 2000 miles. It had been a long, often exhausting trip, but now it was over. We had drunk water that smelled of animals, gone hungry for days, forded rivers, sprained both ankles, sustained fourth degree burns and blisters, and caught a case of poison oak, Mexican style.

We had lost gear, and I felt as though I had sprained my body. Would we do it again? Perhaps, but not soon. Riding a motorcycle 10 to 12 hours a day for three weeks isn’t exactly a vacation, but, for us, it was an exciting experience.

Looking at the map it seemed hard to believe we had traversed so much desert in just three weeks. I looked at my buddy through a swollen eyelid, and said, “If it hadn’t been for the honor of the whole thing, I think I would rather have walked.” He smiled that knowing smile that needs no words. We had come to the end of the Highway of Death, and were still alive to tell the story. ^

Current subscribers can access the complete Cycle World magazine archive Register Now

Frank Taylor

-

History Revisited

History RevisitedTora! Tora! Tora!

AUGUST 1969 By Frank Taylor -

Special Feature

Special Feature"Nobody Who Sees It Is Going To Say: That Was A Nice Picture. They Are Going To Like It Or Hate It. But They Won't Forget It."

DECEMBER 1969 By Frank Taylor -

Desert Riding

Desert RidingThe California-Nevada Deserts

APR 1972 By Frank Taylor