"Nobody Who Sees It Is Going To Say: That Was A Nice Picture. They Are Going To Like It Or Hate It. But They Won't Forget It."

December 1 1969 Frank Taylor"Nobody Who Sees It Is Going To Say: That Was A Nice Picture. They Are Going To Like It Or Hate It. But They Won't Forget It." FRANK TAYLOR December 1 1969

"NOBODY WHO SEES IT IS GOING TO SAY: THAT WAS A NICE PICTURE. THEY ARE GOING TO LIKE IT OR HATE IT. BUT THEY WON'T FORGET IT."

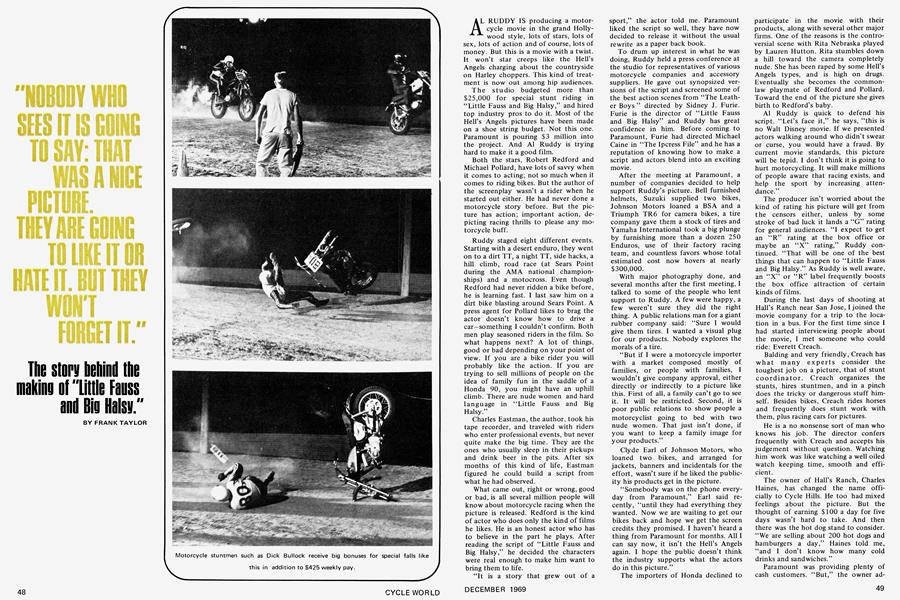

The story behind the making of "Little Fauss and Big Halsy."

FRANK TAYLOR

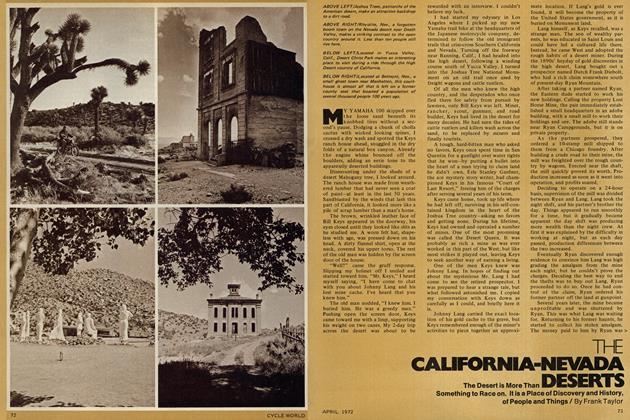

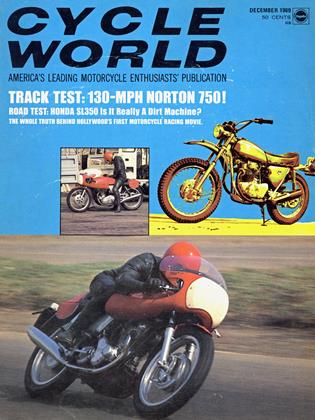

AL RUDDY IS producing a motorcycle movie in the grand Hollywood style, lots of stars, lots of sex, lots of action and of course, lots of money. But this is a movie with a twist. It won't star creeps like the Hell's Angels charging about the countryside on Harley choppers. This kind of treatment is now out among hip audiences.

The studio budgeted more than $25,000 for special stunt riding in “Little Fauss and Big Halsy,” and hired top industry pros to do it. Most of the Hell’s Angels pictures have been made on a shoe string budget. Not this one. Paramount is pouring $3 million into the project. And AÍ Ruddy is trying hard to make it a good film.

Both the stars, Robert Redford and Michael Pollard, have lots of savvy when it comes to acting; not so much when it comes to riding bikes. But the author of the screenplay wasn’t a rider when he started out either. He had never done a motorcycle story before. But the picture has action; important action, depicting racing thrills to please any motorcycle buff.

Ruddy staged eight different events. Starting with a desert enduro, they went on to a dirt TT, a night TT, side hacks, a hill climb, road race (at Sears Point during the AMA national championships) and a motocross. Even though Redford had never ridden a bike before, he is learning fast. I last saw him on a dirt bike blasting around Sears Point. A press agent for Pollard likes to brag the actor doesn’t know how to drive a car—something I couldn’t confirm. Both men play seasoned riders in the film. So what happens next? A lot of things, good or bad depending on your point of view. If you are a bike rider you will probably like the action. If you are trying to sell millions of people on the idea of family fun in the saddle of a Honda 90, you might have an uphill climb. There are nude women and hard language in “Little Fauss and Big Halsy.”

Charles Eastman, the author, took his tape recorder, and traveled with riders who enter professional events, but never quite make the big time. They are the ones who usually sleep in their pickups and drink beer in the pits. After six months of this kind of life, Eastman figured he could build a script from what he had observed.

What came out, right or wrong, good or bad, is all several million people will know about motorcycle racing when the picture is released. Redford is the kind of actor who does only the kind of films he likes. He is an honest actor who has to believe in the part he plays. After reading the script of “Little Fauss and Big Halsy,” he decided the characters were real enough to make him want to bring them to life.

“It is a story that grew out of a sport,” the actor told me. Paramount liked the script so well, they have now decided to release it without the usual rewrite as a paper back book.

To drum up interest in what he was doing, Ruddy held a press conference at the studio for representatives of various motorcycle companies and accessory suppliers. He gave out synopsized versions of the script and screened some of the best action scenes from “The Leather Boys ” directed by Sidney J. Furie. Furie is the director of “Little Fauss and Big Halsy” and Ruddy has great confidence in him. Before coming to Paramount, Furie had directed Michael Caine in “The Ipcress File” and he has a reputation of knowing how to make a script and actors blend into an exciting movie.

After the meeting at Paramount, a number of companies decided to help support Ruddy’s picture. Bell furnished helmets, Suzuki supplied two bikes, Johnson Motors loaned a BSA and a Triumph TR6 for camera bikes, a tire company gave them a stock of tires and Yamaha International took a big plunge by furnishing more than a dozen 250 Enduros, use of their factory racing team, and countless favors whose total estimated cost now hovers at nearly $300,000.

With major photography done, and several months after the first meeting, I talked to some of the people who lent support to Ruddy. A few were happy, a few weren’t sure they did the right thing. A public relations man for a giant rubber company said: “Sure I would give them tires. I wanted a visual plug for our products. Nobody explores the morals of a tire.

“But if I were a motorcycle importer with a market composed mostly of families, or people with families, I wouldn’t give company approval, either directly or indirectly to a picture like this. First of all, a family can’t go to see it. It will be restricted. Second, it is poor public relations to show people a motorcyclist going to bed with two nude women. That just isn’t done, if you want to keep a family image for your products.”

Clyde Earl of Johnson Motors, who loaned two bikes, and arranged for jackets, banners and incidentals for the effort, wasn’t sure if he liked the publicity his products get in the picture.

“Somebody was on the phone everyday from Paramount,” Earl said recently, “until they had everything they wanted. Now we are waiting to get our bikes back and hope we get the screen credits they promised. I haven’t heard a thing from Paramount for months. All I can say now, it isn’t the Hell’s Angels again. I hope the public doesn’t think the industry supports what the actors do in this picture.”

The importers of Honda declined to participate in the movie with their products, along with several other major firms. One of the reasons is the controversial scene with Rita Nebraska played by Lauren Hutton. Rita stumbles down a hill toward the camera completely nude. She has been raped by some Hell’s Angels types, and is high on drugs. Eventually she becomes the commonlaw playmate of Redford and Pollard. Toward the end of the picture she gives birth to Redford’s baby.

AÍ Ruddy is quick to defend his script. “Let’s face it,” he says, “this is no Walt Disney movie. If we presented actors walking around who didn’t swear or curse, you would have a fraud. By current movie standards, this picture will be tepid. I don’t think it is going to hurt motorcycling. It will make millions of people aware that racing exists, and help the sport by increasing attendance.”

The producer isn’t worried about the kind of rating his picture will get from the censors either, unless by some stroke of bad luck it lands a “G” rating for general audiences. “I expect to get an “R” rating at the box office or maybe an “X” rating,” Ruddy continued. “That will be one of the best things that can happen to “Little Fauss and Big Halsy.” As Ruddy is well aware, an “X” or “R” label frequently boosts the box office attraction of certain kinds of films.

During the last days of shooting at Hall’s Ranch near San Jose, I joined the movie company for a trip to the location in a bus. For the first time since I had started interviewing people about the movie, I met someone who could ride: Everett Creach.

Balding and very friendly, Creach has what many experts consider the toughest job on a picture, that of stunt coordinator. Creach organizes the stunts, hires stuntmen, and in a pinch does the tricky or dangerous stuff himself. Besides bikes, Creach rides horses and frequently does stunt work with them, plus racing cars for pictures.

He is a no nonsense sort of man who knows his job. The director confers frequently with Creach and accepts his judgement without question. Watching him work was like watching a well oiled watch keeping time, smooth and efficient.

The owner of Hall’s Ranch, Charles Haines, has changed the name officially to Cycle Hills. He too had mixed feelings about the picture. But the thought of earning $100 a day for five days wasn’t hard to take. And then there was the hot dog stand to consider. “We are selling about 200 hot dogs and hamburgers a day,” Haines told me, “and I don’t know how many cold drinks and sandwiches.”

Paramount was providing plenty of cash customers. “But,” the owner admitted, “I was worried about them coming here to make a motorcycle movie at first. I was afraid undesirables would show up, but that hasn’t happened. I don’t like the idea of naked women and drugs in the picture, but I guess it will be okay.” he concluded.

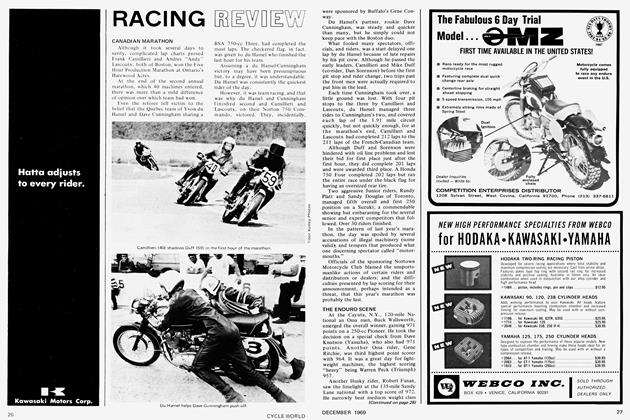

Creach had set up a motocross scene for his riders.

The director was using a $50,000 camera truck to hold the main camera and the driver turned out to be an old dirt track racer who once captained the Gilmore Racing Team in Los Angeles. Jerry Gerard used the name Gerard Courian in his racing days and was enjoying his front seat view.

As we watched, the director asked Creach to arrange a spill for the cameras on a banked turn. The stuntman nodded and selected a rider for the task. Spectators were asked to stand on the outside edge of the track where the spill was to take place.

Gerard shook his head when he saw that. “They would never allow people to stand on the outside edge of the track,” the driver told me, “it is too dangerous.” On cue, a rider flopped his mount and went skidding into the crowd of extras. The people scattered in all directions, adding to the realism. Within a few seconds three other riders were down in the same place and a cloud of dust had boiled up.

“I don’t like all the swearing,” Gerard went on, “It doesn’t need to be in a picture like this. The action is so good you don’t need foul language to color things up. Sure people talk like that sometimes, but why add it to a terrific picture.”

Creach moved his men to a dry stream bed where a new part of the action was to be filmed. The extras followed his lead. The atmospheric actors had been recruited from advertisements in local papers. Stage-struck kids, hippies with bushy hair matted with dirt, tattooed men, bare bellied punks, and young girls with bare feet were all told where to stand by the assistant director.

Hopping on a Triumph, Creach explored the course first. The cameramen set up their gear and checked him for framing. The course was laced with oak trees and light streamed through the branches overhead. The shadows were cool, a welcome relief from the blistering sun. After checking the trail, Creach conferred with his riders.

The stuntmen had been reinforced in number by local bikes, so Creach wanted them to understand how they were to behave on camera. At last the film crew was ready and Furie gave the signal to start. With an ear-splitting roar, the pack split up and poured over the lip of a hill heading for the cameras. Creach was in the lead, easily distancing the others.

He picked the roughest spots for himself, easily tossing his weight from side to side for balance. As he flashed by the cameras with a burst of throttle, a billowing cloud of dust floated up behind him. Behind Creach, the others weren’t doing too well. A San Jose rider went down accidentally and flipped a fellow actor. Only the stuntmen seemed to be really working the course, the others looked a bit nervous and frightened.

“Can you do it any faster?” the director asked Creach. The stuntman nodded. Roaring back to their starting point, the pack tried to outdo each other with wheelies on the hard packed service road. The second pass was a duplicate of the first. Only Creach rode it faster than the previous “take.” Local riders were still having trouble staying on their bikes. But Furie was satisfied and the cameramen moved their gear to a new location.

Selecting an open spot in the trees, Creach paced off a stunt fall in the soft dirt. An assistant director hustled the extras into place with his bull horn. The first riders shot through the dirt trap like bullets. The man selected to fall locked his front brake and dumped the machine. As he tried to right the bike, other riders, mostly stuntmen, blasted past. It was a terrific scene. But Creach wasn’t through yet.

Asking for another run, Creach waited until a rider had just gone by and yanked the startled man out of the saddle. Cameras set up nearby recorded the action as a spectator accidentally bumped into a contestant causing him to fall. The dust was thick now. Everyone was choking from the clogged air. At a signal from the assistant director the company broke up. The scene was finished.

Creach sat on his bike under a tree. He was surrounded by his regular stunt riders. All of them were crusted with dirt, which mingled with sweat and grease and turned to a thin layer of dried mud. Their leathers were filthy from their morning chores. “From my point of view,” Creach told me, “this is the best film that has ever come out in support of motorcycles. The director gives me a free hand to set up stunts and I have the best riders in the country for this kind of work.”

Motioning toward his men, Creach went on, “I trust these guys, and I bunch them around me in a scene, then we use local riders as backups. We can do anything the director wants, short of killing somebody.” His riders grinned. “My stunts come as a surprise to the audience. Sometimes they are a surprise to my men, too. I set them up quick and we do them quick. We can’t waste time. This picture is costing too much money.”

Creach has a bigger job on his hands than a race promoter. Not only does he have to capture all the action possible, he ensures that it looks authentic, and stages the spills and hard riding where the camera can shoot it. In Arizona he was directing over 200 riders under the worst possible conditions. Normally however, his complement of riders is about 25 or 30. Besides being spectacular, his stunts must be safe. Neither Paramount nor Creach wants anyone to get hurt.

Everett Creach is no ordinary stuntman. He holds a director’s card which is about as hard to land as a free sample from Fort Knox. In his next assignment, he will probably do second unit direction. This means the lesser parts of a picture that require less of the director’s attention can be assigned to experienced men like Creach to handle. In Hollywood, this is a signal honor.

“I don’t pay much attention to what the stars do,” he went on, “my job is to get action, and keep my stuntmen happy. What the director and the actors do is no concern of mine. My racing scenes are real. Dramatics are up to the director.” His stunt riders generally felt the same way. “We don’t see much of the regular acting,” one said, “so I don’t know what that will be like. But I know what I have been doing is hairy.”

The hard core of Creach’s riders came from the exclusive Viewfinders club—a dedicated group who work in the motion picture industry, own motorcycles and are over 21. Lynn Guthrie, an assistant director on “Little Fauss and Big Halsy,” was one of the founders.

“We started the club with 20 charter members,” Guthrie said, and now it is around 88. Everett Creach was one of the original members too.” The group is planning a Grand Prix for 1970 and will probably hold it on the Paramount Ranch near Hollywood. During the 1968-9 season the Viewfinders held two major races at Westlake, a community west of Los Angeles.

One of the camera bikes was sitting nearby and Guthrie pointed at it. “If someone was giving an award for the worst handling bike in the world, those camera bikes would have to take the prize. There is 140 extra pounds of dead weight, bolted on at awkward places, making it a job to even hold them up, let alone mix with a pack of bikes on a cross-country run or ride in a pack, making film.”

The mounts varied. One of the worst was a pipe arrangement that hung low off one side of the machine. When making a turn the pipes dug into the ground causing some scary moments for the rider. Finally in desperation, Creach, who did most of the camera work on the picture, used the pipe mount as a skid and slid the bike on it.

Stunt riders according to Guthrie earn $425 per week as a base pay. Added to this is any overtime that might come up, and bonus pay for planned spills. If you crack up accidentally—too bad, chum, no pay. The spill might be the best one you have ever done for the camera, but if it wasn’t ordered by Creach or the director, you did a free stunt.

Naturally, stuntmen hope they will be given extra work to do. “They have to do stunts,” Guthrie pointed out, “it is their living. If they can’t make a few extra bucks on a spill, they will have a short pay check.” There was a friendly inter-rider penalty going on during the shooting of races. Everytime a man took an unexpected spill, he had to put $5 in the pot. Some days when action was brisk and a lot of local riders were on the set, the pot reached $120. This would be spent at night buying drinks for everyone.

Trying to earn a living as a stuntman is no bed of roses. For a simple flip with a bike, the rider will get a $150 bonus. If it is more dangerous, the amount goes up. Dick Bullock was given the task of loosing a wheel at 60 mph on a dirt track by Creach. Taking the nuts off the front wheel, Creach told the rider to kick his bike up to speed, pull a wheelie, then let Nature take its course.

Bullock did as he was told. As he shot past the camera, he hauled back on the front end and the wheel dropped out. But instead of rolling out of the way, the wheel flopped flat in the track and the rear wheel of Bullock’s bike smashed into it. Bullock was thrown like a rag doll in a somersault and hurled to the ground with the force of a falling locomotive. The dirt was like concrete. His bike corkscrewed into the air and landed 30 feet away.

Sidney Furie was very happy. The stunt looks spectacular on the screen, and no one would ever suspect it was staged. For his part, Dick Bullock can only remember how much that fall hurt. “After the bike hit the wheel, all I could think about was, save the body,” he admitted later. Because of the danger, and the risk, Bullock was given a reported $750 to soothe his feelings.

Most stuntmen prefer the stunts that are set up on the spur of the moment. The anticipation can grate on the nerves—even the normally cool nerves of a professional. Creach has become famous for this style of planning. A recent example was a dirt track race he staged at Cycle Hills. The riders were to pour down a hill and make a tight turn. The director asked his stunt coordinator to have a rider peel off the track and crash a barricade.

MOTORCYCLE MOVIE

With hardly a moment’s hesitation, Creach gave the assignment to a rider and the whole troupe roared off. As the cameras ground away, the man leaped the edge of the track and slammed head on into the barricade. Everyone was delighted—including the rider who received a nice “bonus” for his crash. Without trained and experienced riders like the Viewfinders, Creach would be hard put to achieve such fast results for the cameras.

Fortunately, none of his men joined the “white boot” club. In the whole shooting schedule there were no serious accidents or broken bones. A remarkable feat. A few of the riders who turned out to watch the action weren’t so lucky. Several of them were wearing the plaster badges of their indiscretions on a motorcycle. Evidently they hadn’t learned the secret of “saving the body” like the pros.

The movie company was at Cycle Hills five days. The action captured there would probably run less than two minutes on the screen, but that’s the way a major movie is shot. A Hell’s Angel picture would probably have a total shooting schedule of two or three weeks. AÍ Ruddy and Paramount are very serious about their product.

Besides the usual problems encountered in movie making, the weather was intolerable. The first weeks of shooting took place outside Phoenix, Ariz., in a little desert valley. The July heat charbroiled the company. Strong winds and heat approaching 120 degrees turned the desert into an oven. Delicate movie equipment was filled with dirt and grime.

When the movie makers finished in Arizona, everyone heaved a sigh of relief. But it was a case of jumping out of the frying pan into the fire. At Willow Springs, California, where the cameras were set up next, the worst heat wave in memory wafted in. The blistering sun baked the semi desert location, magnified by the pavement of the race track where the bikes were running. Both men and machines started to come un-glued.

Dressed in full leathers and helmets, the riders could only do two laps of the track at a time. After a run for the cameras, the men would peel out of the protective clothing for a quick breather. Engines seized and blew up, and mechanics assigned to the picture were busy around the clock trying to keep up with repairs.

After weeks of this, the movie footage was superb, but the toll of human suffering was great. Again, this period of shooting will be boiled down to less than three minutes on finished film. To zero in on the men and machines, a helicopter with a camera mounted on it hovered over the track almost brushing the heads of the riders. But the heat at Willow Springs forced the company to halt shooting at 3 p.m. No humans could have endured more of the soaring temperatures and exertions without falling prey to accidents or heat prostration. To try and keep things rolling as long as possible, the director would switch riders. Moving from mount to mount in this way, it was possible to stretch human endurance a bit longer. But, finally, the schedule had to be readjusted.

Stuntmen and actors weren’t the only ones struggling with the heat however. Ralph Woolsey, director of photography and a member of the American Society of Cinematographers, found he needed every bit of ingenuity he possesed to get his scenes on film. Woolsey was in charge of more than $500,000 worth of fragile camera gear and rolling stock.

The Panavision Arriflex 35-mm cameras were mounted on a special frame bolted to the motorcycle. Normally, shots of a motorcycle race would be made from a camera truck, but Woolsey wanted to involve his audience with what was transpiring on the screen. To do this, he needed the cameras in the midst of the action.

The first frames and cameras were too heavy for the forks of the smaller Japanese bikes. After beefing these up, the forks carried the load perfectly. Woolsey developed 10 basic positions for his cameras. Through trial and error, brackets were devised that let the camera look over the shoulder of rider, record his foot action, shoot straight ahead, in back, to the side and a number of variations in between.

But a $50,000 camera isn’t something you write off after one take. Besides recording action, Woolsey had to protect his equipment. Dirt and heat were the most serious problems. Both are the cameraman’s enemy. To seal out dirt and reduce temperatures which could spoil film, the cameraman wrapped his charges in tin foil. The bright surface reflected heat and kept most of the dirt out.

He couldn’t risk a broken lens from a flying stone either, so Woolsey put a piece of optical glass in front of the lens mount and staved off serious damage. But as good as Woolsey’s precautions were the camera repairman assigned to the picture often worked around the clock. In fact, because of the dramatic nature of his efforts, Ralph Woolsey might win an Academy Award nomination next year.

As the bikes were being packed away, AÍ Ruddy said, “Before I started “Little Fauss and Big Halsy,” I had over 100 scripts you couldn’t loose money on, but I picked this one because I believed in it. There is a certain gritty texture in motorcycle racing that can’t be found in any other sport. This story is real to me. I think it will be real to audiences.”

Robert Redford stopped to take a look at some streamlined bikes that had been delivered to the set. His co-star, Michael J. Pollard was rushing off to his dressing room trailer wearing his famous grin and a shock of long, stringy hair. Ruddy nodded briefly at both of them and resumed our conversation. “My picture could be next year’s “Bonnie and Clyde” or “The Graduate.” I want people to get turned on who don’t know anything about bikes. This is a young peoples’ story. If the motorcycle industry doesn’t sell a million bikes the first year after this picture comes out, I will be surprised.”

Redford, the star, said: “Nobody who sees it is going to say ‘That was a nice picture.’ They are going to like it or hate it. But they won’t forget it.” I am inclined to agree with Redford.

“Little Fauss and Big Halsy” might be the biggest boost for motorcycling the United States has ever seen on a movie screen—or it could be the industry’s worst public relations job since Marlon Brando mumbled his way through “The Wild One.” But Clyde Earl was right about one thing. It is not just another Hell’s Angel film.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue