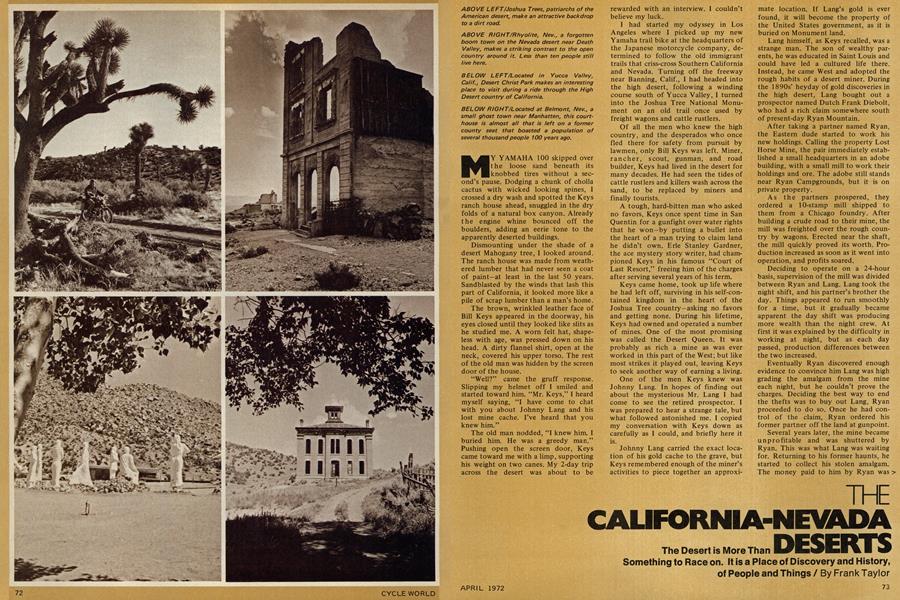

THE CALIFORNIA-NEVADA DESERTS

The Desert is More Than Something to Race on. It is a Place of Discovery and History, of People and Things

Frank Taylor

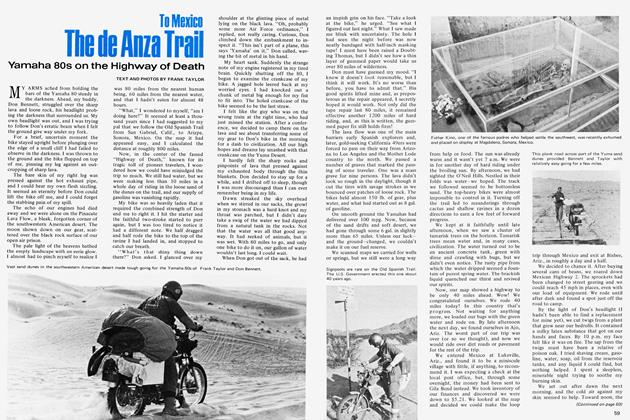

MY YAMAHA 100 skipped over the loose sand beneath its knobbed tires without a second’s pause. Dodging a chunk of cholla cactus with wicked looking spines, I crossed a dry wash and spotted the Keys ranch house ahead, snuggled in the dry folds of a natural box canyon. Already the engine whine bounced off the boulders, adding an eerie tone to the apparently deserted buildings.

Dismounting under the shade of a desert Mahogany tree, I looked around. The ranch house was made from weathered lumber that had never seen a coat of paint—at least in the last 50 years. Sandblasted by the winds that lash this part of California, it looked more like a pile of scrap lumber than a man’s home.

The brown, wrinkled leather face of Bill Keys appeared in the doorway, his eyes closed until they looked like slits as he studied me. A worn felt hat, shapeless with age, was pressed down on his head. A dirty flannel shirt, open at the neck, covered his upper torso. The rest of the old man was hidden by the screen door of the house.

“Well?” came the gruff response. Slipping my helmet off I smiled and started toward him. “Mr. Keys,” I heard myself saying, “I have come to chat with you about Johnny Lang and his lost mine cache. I’ve heard that you knew him.”

The old man nodded, “I knew him. I buried him. He was a greedy man.” Pushing open the screen door, Keys came toward me with a limp, supporting his weight on two canes. My 2-day trip across the desert was about to be rewarded with an interview. I couldn’t believe my luck.

I had started my odyssey in Los Angeles where I picked up my new Yamaha trail bike at the headquarters of the Japanese motorcycle company, determined to follow the old immigrant trails that criss-cross Southern California and Nevada. Turning off the freeway near Banning, Calif., I had headed into the high desert, following a winding course south of Yucca Valley, I turned into the Joshua Tree National Monument on an old trail once used by freight wagons and cattle rustlers.

Of all the men who knew the high country, and the desperados who once fled there for safety from pursuit by lawmen, only Bill Keys was left. Miner, rancher, scout, gunman, and road builder, Keys had lived in the desert for many decades. He had seen the tides of cattle rustlers and killers wash across the sand, to be replaced by miners and finally tourists.

A tough, hard-bitten man who asked no favors, Keys once spent time in San Quentin for a gunfight over water rights that he won—by putting a bullet into the heart of a man trying to claim land he didn’t own. Erie Stanley Gardner, the ace mystery story writer, had championed Keys in his famous “Court of Last Resort,” freeing him of the charges after serving several years of his term.

Keys came home, took up life where he had left off, surviving in his self-contained kingdom in the heart of the Joshua Tree country—asking no favors and getting none. During his lifetime, Keys had owned and operated a number of mines. One of the most promising was called the Desert Queen. It was probably as rich a mine as was ever worked in this part of the West; but like most strikes it played out, leaving Keys to seek another way of earning a living.

One of the men Keys knew was Johnny Lang. In hopes of finding out about the mysterious Mr. Lang I had come to see the retired prospector. I was prepared to hear a strange tale, but what followed astonished me. I copied my conversation with Keys down as carefully as I could, and briefly here it is.

Johnny Lang carried the exact location of his gold cache to the grave, but Keys remembered enough of the miner’s activities to piece together an approximate location. If Lang’s gold is ever found, it will become the property of the United States government, as it is buried on Monument land.

Lang himself, as Keys recalled, was a strange man. The son of wealthy parents, he was educated in Saint Louis and could have led a cultured life there. Instead, he came West and adopted the rough habits of a desert miner. During the 1890s’ heyday of gold discoveries in the high desert, Lang bought out a prospector named Dutch Frank Diebolt, who had a rich claim somewhere south of present-day Ryan Mountain.

After taking a partner named Ryan, the Eastern dude started to work his new holdings. Calling the property Lost Horse Mine, the pair immediately established a small headquarters in an adobe building, with a small mill to work their holdings and ore. The adobe still stands near Ryan Campgrounds, but it is on private property.

As the partners prospered, they ordered a 10-stamp mill shipped to them from a Chicago foundry. After building a crude road to their mine, the mill was freighted over the rough country by wagons. Erected near the shaft, the mill quickly proved its worth. Production increased as soon as it went into operation, and profits soared.

Deciding to operate on a 24-hour basis, supervision of the mill was divided between Ryan and Lang. Lang took the night shift, and his partner’s brother the day. Things appeared to run smoothly for a time, but it gradually became apparent the day shift was producing more wealth than the night crew. At first it was explained by the difficulty in working at night, but as each day passed, production differences between the two increased.

Eventually Ryan discovered enough evidence to convince him Lang was high grading the amalgam from the mine each night, but he couldn’t prove the charges. Deciding the best way to end the thefts was to buy out Lang, Ryan proceeded to do so. Once he had control of the claim, Ryan ordered his former partner off the land at gunpoint.

Several years later, the mine became unprofitable and was shuttered by Ryan. This was what Lang was waiting for. Returning to his former haunts, he started to collect his stolen amalgam. The money paid to him by Ryan was > gone and his attempts to find a new mine had failed, but now he had a rich horde of nearly raw gold to dig up at leisure.

Continued from page 73

Treks to recover his stolen gold began about 1917, Keys thinks, and continued for nearly ten years after that. Twice a year, Lang would come to Keys with gold, almost always the same amount, $980 worth. Keys would ship this with his own ore to the mint in San Francisco, taking the suspicion off Lang—because he couldn’t prove he had a claim.

During the winter of 1926, a bitter cold wind swept through the high desert, bringing in its wake deep snowdrifts. Now an old man, Lang was still driven by greed, and unwisely started out to his cache at the Lost Horse Mine. He must have found what he went after, then started back. On his return, death overtook him in a lonely camp on the open desert, and Johnny Lang left this world’s cares behind him.

When Lang didn’t reappear, Keys and three of his friends started to look for him. They came upon the prospector, still wrapped in his bedroll, and nearly frozen solid. A grave was dug, and his canvas sleeping bag was used as an improvised coffin.

The miner’s death closely paralleled that of his father, who also perished in a snowstorm, but in Alaska. Both men had died with money in their pockets— Johnny with rich gold amalgam, his father with American greenbacks. Both men had been warned about making the trip because of bad weather conditions.

Years later, Keys carved a granite headstone for his old friend, and used it to mark the spot where Lang had died. Keys was no longer sure how much gold was left at the Lost Horse Mine that Lang never had a chance to recover, but he assumes it must have been considerable.

Keys gave me a few clues about the treasure that sounded very intriguing. He knew, for instance, that Lang used a small clay pestai to hold the ore, then placed a rock over it. The clay crucibles were then buried near his cabin each night. Each one was probably worth $1000 then, and twice that amount today.

The sun had sunk behind the hills by the time Keys finished his story, and I was invited to spend the night at his ranch, camping in the yard near his reservoir. After spreading out my bedroll and settling things down for the night, I went back to the cabin and Keys talked far into the night about his life.

I learned, for instance, he had once been a partner of Death Valley Scotty, and had been accused of cattle rustling—but never convicted. His dim blue eyes lit up at the suggestion he had once been on the wrong side of the law, but he refused to say more.

With dawn creeping over the desert, I waved goodbye to Bill Keys for the last time—he died a few weeks after I left him. Stopping for a few minutes at the Keys’ family cemetary where Keys’ wife and children lay buried, it was impossible not to be touched by the handhued tombstones Keys made for each member of his family. A paved road leading to Salton View cuts cross-country past the grave of Johnny Lang. Less than hundred feet south, a dirt road cuts to the left. This is the road to Lost Horse Mine. For the first few miles it follows the flat floor of the valley, then it abruptly cuts into the hills.

I was grateful for the quick shift lever on the Yamaha that allowed me to change gear ratios. It was certainly needed to climb the rough mine road and dodge the big rocks, most of which were the size of a man’s head, that littered the trail. It was an easy ride of about five miles to the deserted mine buildings through hillsides covered with Yucca plants starting to burst into bloom.

The most dominating feature of the Lost Horse Mine was the mill. Supported by heavy timbers, the 10-stamp mill was stopped in mid-motion when the miners left. Two shacks remain, but they are poised on the verge of collapse. Could one of them have been Lang’s? It is doubtful. The foundations of several more structures were easy to find in the brush, so it would be anyone’s guess where Lang lived and hid his cache.

Climbing up to the mill, I could see San Jacinto and San Gorgonio, two of Southern California’s highest peaks, to the west. Both were snow crowned and stood like sentinels in the distance. I cleared off a smooth piece of land, and set up camp. A cold wind had started to blow, and before I set out for Pinto Basin, another mining camp, I resolved to get a good night’s sleep.

I took a little-known road over the hills the next morning that led to the broad Pinto Basin, once the haunt of prehistoric man, and a favorite campground of local Indians. Two roads slice up the basin, and the hills are dotted with abandoned mines. One of them, the Gold Bug Mine, yielded enormous riches before closing.

The bike hummed through the choking dust that blasted me when hot winds tore across the landscape. I was heading for a mine known as Virginia Dale to look over the ruins I had heard about. Below the mine in the shifting sands lay the almost forgotten community of Virginia Dale. Not a building remains of this town, but the cemetary is supposed to be worth a visit—if you can find it. At the mine, I explored ruins, checked out a shaft that might yield a few gemstones, and enjoyed the view which stretched for miles in all directions.

I could trace the old Indian trail that once connected the hot springs at Palm Springs with the Mojave Desert and Colorado River. The path probably hadn’t been used for at least a century, yet it was still easy to spot in the hard sand. Infrequent rains prevent them from being washed away. Souvenir hunters like to follow these trails, because many relics are frequently found which were discarded or lost by passing Indians.

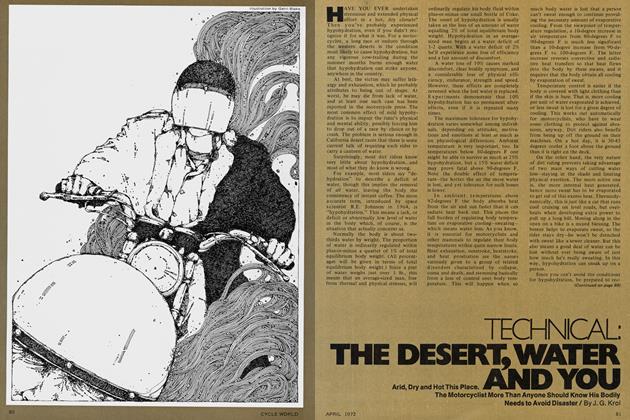

The climb up to the mine was the roughest I have ever encountered in recent memory. Again, the curse of big rocks, rolling loose on the rutted surface, jerked the bike out of control. I found myself constantly slipping backward, or teetering toward the cliff-like edge of the road—which would have meant a few broken bones if I had toppled over.

During one of these bouncing ascents, the Yamaha flipped backward, landing on my head and chest. The crash helmet saved my skull, but I got a nasty set of bruises on the chest. The handbrake lever broke in the spill, but aside from scratches, the bike was fine. A veteran of several such desert trips, I have learned to depend on Yamaha for rough treatment in tight spots like this, and the trail bike proved its worth.

Loading up the spilled gear, I started down the steep trail leading toward Twenty nine Palms, handicapped by the loss of my front brake. The sun was hot—too hot for comfort—and the dry wind did little to ease the discomfort of riding out of the scorched hills of the Pinto Basin.

Past Amboy, a miniscule wide spot in the road, the bike overheated, and I was forced to stop. Something had clogged the oil injection system, and I spent a grim three hours struggling with the unit, until it was functioning again.

East of Amboy I turned north, skirting the edge of the Old Dad Mountains, following a dirt road that splits the desert between Route 66 and 15. I had decided to camp another night in the desert and was seeking water at Baker to refill my canteens, when the lights of Kelso hove into view. I had never been to this remote corner of the world, bounded on one side by the infamous Devils Playground sand dunes, and on the other by the Santa Fe Railroad tracks.

Once Kelso had been a water station for trains; now it is a pinprick of life that centers around a hotel, of all things! The few deserted houses and an old school speak of a time when probably 100 people lived there—now the sum total is certain to be less than 15, on a good day. (Continued on page 79)

Continued from page 74

The Kelso Hotel had a bright neon light burning announcing it was open, so I rolled up in the parking lot and dismounted. Shaded by tall trees and a wide, veranda-like porch, the building is sturdy and cool in the summer months. The restaurant was open (I later found out it will serve meals 24 hours a day), even though the place is nearly 40 miles in any direction from a town of any size. The meal was delicious, and reasonably priced, and when I discovered rooms were $2.50 a night (including a shower) I forgot about a camp under the stars.

I had barely settled into a deep sleep in my room when a roar like thunder shook the room. Awake and out of bed in my underwear, I was ready to make a run for it, figuring an earthquake had struck, when a piercing whistle told my jangled nerves a freight train had just passed through Kelso about ten feet from my room! The rest of the night was spent alternating between the passing trains and sleep. I was happy to chow down in the morning and head for the open desert again. At least there one can be sure of peace and quiet.

Between Kelso and Cima, another tiny place hardly worth a mention on the map, is a paved road. North of Cima and south of Kelso the access roads are dirt, but for this one stretch it is paved. Later an explanation was offered, by a local. During WW II, Kaiser, who ran a mine nearby, had built the paved part of the road for his mine trucks so they could carry ore to the train fasterincreasing the profits.

I linked up with Highway 15 at Windmill Station, and rode over Mountain Pass, the last big summit (4731) before reaching the California Line. I passed through Las Vegas without a second look—gambling isn’t my bag, and besides after nearly a week in the desert, I hardly looked like a refugee from the sidewalks of Los Angeles.

About 25 miles north of Sin City, I pulled into the Corn Creek Field Station where the only captive bighorn sheep in the U.S. are kept for study. A two or three mile dirt road leads to the station, which was once a wagon stopover in pioneer days on the Austin-Las Vegas run.

The rangers showed me the small museum they had built, and talked about the wiley bighorn they are committed to protect in the governmentsponsored range. Since no camping is allowed after sunset, I left early enough to make a run ten miles south to a park just west of the highway to camp for the night.

Before dawn, I was asked to leave by a member of the sheriffs department, because it seems no camping was allowed. Ho hum. While it was unexpected, I viewed the early morning roust as a chance to beat the heat and head for Rhyolite, Nev., a former ghost town between Death Valley and Beatty, a small town founded nearly a century ago by a wandering rancher.

Rhyolite is probably the oddest ghost town I have ever seen. Built of concrete instead of wood, the ruins speak of a time when gold was worth mining, and a boom town could spring up overnight with a population of several thousand persons. The town is five miles west of Beatty, and is reached by a dirt road that was once the road bed of the Tidewater & Tonopah Railroad.

Again I was surprised to see a train station. The Rhyolite station is built from stone and was supposed to have been the best building of its type in Western America for a community of its size. Now it is 200 miles from a railroad in any direction. It is operated by a couple who open the station up, when the mood strikes them, as a museum. They weren’t answering their door the day I stopped, but down the road Tommy Thompson and his wife greeted me with open arms.

The Thompsons live in a glass house—and love every minute of it. Their house is built from more than 50,000 antique beer and whiskey bottles, collected about 1905 by the home’s first architect and builder. Now more than 65 years old, the house is a rustic bit of Americana that has become a shrine of history. The empty flasks were imbeded in raw adobe earth to form the 4-room structure.

Sought by collectors, the house is valued at a minimum of $1 to $10 per bottle. “We live in a gold mine,” Thompson admits, “but we are also helping to preserve a part of history that will never be seen again. If we didn’t stay here and keep an eye on things, the walls would be picked clean in a week by collectors.”

Thompson is one of those rare persons, seldom seen in these commercial times, who doesn’t charge for people to see his attraction. “We have all the money we need,” he grinned, tilting his hat at a jaunty angle, “so why charge people? We enjoy having them stop in.”

A former accordion player and circus acrobat, Thompson has been working in Nevada and other parts of the world for more than 70 years. He won’t give his exact age, but admits he is now in his eighties, and doesn’t plan an early retirement.

He invited me to camp near the bottle house and to spend a few days, but I was anxious to head up the road, and declined his hospitality. As the bike roared to life, a dozen dogs from the Thompson kennel started to bark. It was a noisy send-off from this peculiar town with less than eight residents, but somehow it seemed to fit the rest of the oddball nature of Rhyolite.

I had a long ride to my next planned stop, Goldfield, almost 70 miles away. The little Yamaha was dependable, but slow on the highway, and I figured I had better give myself all the lead time I could. The late afternoon sun was casting deep shadows across the deserted street of Rhyolite as I waved farewell to the Thompsons and started north.

It was a tempting thought to turn west and make a detour through Death Valley with a stop at Death Valley Scotty’s Castle, but it was late May and the temperatures in America’s Basement were starting to soar into the 120-degree region, and it was hot enough were I was. Traffic between Beatty and Goldfield was heavy, and I longed for a bigger machine that would have enabled me to keep pace—but that was not to be. At least I was getting better mileage than anyone who passed me, for whatever consolation that was.

Once a booming gold mining center, Goldfield is like many other towns in Nevada, a mere shadow of its former glory. The hotel is big—over 160 rooms, yet not a soul has lived there since 1945. The rooms still have their original furnishings, brass beds, and expensive hardwood furniture, installed about 1907, but the only occupant is Arthur Trevor, a resident caretaker.

It was after dark and I was anxious to find a camping spot, so I followed a trail until I was outside of town and the town lights were only a flicker on the horizon. The crickets kept me company as I made camp. This particular evening was one of the best on the trip. A soft, warm breeze was blowing across the desert from Rabbit Springs, a canyon directly opposite my camp about four miles.

After riding around the remains of Goldfield for about an hour, I turned north again, this time for Tonopah, a modern city that started as a boom town in 1900. Passing through Tonopah to the curious stares of school children,

I went east six miles to Nevada Route 8A that winds through Smokey Valley between Austin and Tonopah.

The road is funneled between two mountain ranges, the Toiyabe on the west and Toquimas on the east. It was a smooth, pleasant journey to my first stop, Manhattan, a tiny community perched on the slopes of a steep canyon.

I found little in Manhattan to excite my interest, although it is apparent this too was once a busy place.

A quaint old church stands on a hillside overlooking the town, but it hasn’t been the location of service in two decades—if not more. Heading west,

I left the poorly maintained blacktop road and started to bump over a graded dirt road that connects the Monitor Valley with Manhattan.

(Continued on page 98)

Continued from page 79

I had heard about Belmont, the former county seat, abandoned in the 19th Century for more prosperous Tonopah, with its expensive brick courthouse, and I was curious to see it. I didn’t have long to wait. The trip between towns was short. I first spotted Belmont by the over 50-ft. tall chimney that marks the former site of the Monitor Mill, just south of town.

It seemed impossible such a tall, well-made chimney could have survived the ravages of time, or even have been needed in the first place, but here it was. Since I couldn’t ride to it on the bike, I dismounted and walked over. The brick work was so astonishing, and perfect on the chimney that I found it hard to believe.

The rest of the structure, also made from brick at some prosperous time in the past, was also in evidence, but in ruins. Around the bend lay Belmont. The brick courthouse was more imposing than I previously thought, but vandals had broken all the windows, torn out lumber inside in a frantic search for square nails, and generally rendered the once proud structure a shambles.

A well-made stone house that was the local mining company office is the current home of Rose Kennedy, a lifetime resident of Belmont. I stopped to talk with her, but she was out of town on an errand, and I missed the opportunity to hear some of her stories about early Belmont.

A local resident made it clear I wouldn’t be welcome if I was planning to stay in town, but suggested a spring used by cattlemen outside of town. Taking his advice, I rode up the road and found the spring. A water trough with clear (well almost clear) sparkling water that bubbled out of a spring greeted me, and I found a comfortable spot under a Juniper tree to camp.

It was unfortunate, but someone had already visited the spring and dumped what appeared to be a trailer load of household garbage in the brush. I spent about two hours gathering it all up and burning it with the aid of some gas from the Yamaha tank—so the next visitor would have a clean camp to enjoy.

Back in Belmont, I talked with a man who had lived in the community most of his life, Frank Brotherton. Brotherton’s relations once operated the only undertaking parlor in Belmont, in what had also been the town jail.

Located in the basement of a collapsed store, whose roof was leaking from a recent rain, the jail has heavy steel doors, and slimy, damp walls. Once locked inside, a felon had no chance of escape. As we poked around in the room, Brotherton showed me a set of burial clothes, and silver coffin handles left over from more prosperous times. It was a chilling experience—especially when Brotherton told me two men had been hanged, then shot in the room we were standing in!

Other buildings seemed on the verge of collapse from old age. For all the decay, however, Belmont had a certain charm that is hard to describe. I hope to go back again for a longer stay sometime in the future. Kicking over my bike, I started up the road. A kindly soul waved me down.

“Did you know the spring you stayed at was infested with rattlesnakes?” the man asked with a slight grin.

“No,” I admitted, “but they didn’t bother me.” The man looked disappointed with my admission, especially since I was obviously safe and sound. “That’s the breaks,” I smiled over my shoulder.

I exited from the Monitor Valley at a point about midway between Austin and Eureka. Consulting my maps, I decided to take the road toward Austin, one of the oldest towns in the state. By coincidence or chance, it is located near the geographical center of Nevada.

A steep grade winds into the sleepy community tacked like building blocks on the steep hillsides of a canyon. One of the local features are ladders leading to second-story apartments in many of the oldest stores. These could be pulled up at night to keep thieves and intruders at a safe distance.

People in Austin were friendly—some of the most outgoing I met on the trip. The general store, full of rich smells from many types of merchandise, reminded me of America several decades ago. A free tour map prepared by the Chamber of Commerce guides visitors to the many points of interest, and I set out to explore them all.

If there was a favorite, Stokes Castle was probably it. A tall, narrow structure, the “castle” really doesn’t look like a castle, but it was still impressive. Several stories high, fire had gutted the interior and burned the roof off, leaving only a stone shell, but I couldn’t help wondering about the eccentric man who built it.

Following Highway 50 west from Austin, I was heading for Reno and home via Carson City. Even though the trip had been fun, the constant jolting and straining of keeping a trail bike on course in the backcountry was starting to show.

Counting all my wanderings, sometimes in circles, to see attractions along the route, the speedometer registered more than 2600 miles. The engine still purred to life every morning, and except for one flat tire and a few stray nuts and bolts that fell off, the bike felt new, and looked it.

I passed through Carson City late at night, following Highway 395 toward Los Angeles, down the backbone of the eastern Sierras. The nights at this altitude were cold, and I usually pulled into one of the state-operated campsites an hour before dark to avoid the chill air generated by riding.

My last night on the road, I unrolled my bag near the community of Lone Pine and settled down around the campfire. Above, a canopy of stars winked at me, and to the west, Mt. Whitney gleamed in the failing light, a brilliant diamond of snow against the dark sky.

Brushed by a light breeze, I wondered why I was going back to Los Angeles and smog—after nearly two hours of contemplation, no answer came, but I knew I would go back anyway. People are funny, no doubt about it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue