FEEDBACK

Readers are invited to have their say about motorcycles they own or have owned. Anything is fair game: performance, handling, reliability, service, parts availability, funkiness, lovability, you name it. Suggestions: be objective, be fair, no wildly emotional but illfounded invectives; include useful facts like miles on odometer, time owned, model year, special equipment and accessories bought, etc.

'71 BSA 500

I am writing concerning my motorcycle and my dealer. First, the bike. It’s a BSA Gold Star 500cc, 1971 model. I purchased it in September and as of this writing (in mid-November) it has 500 miles, 300 of which were used in trips back and forth to the dealer. I have had eight days use of the bike. It leaks oil everywhere, has gone through two batteries, a transmission mainshaft, a starter gear, has holed the gas tank with an engine head bolt, vibrates like crazy and all the red paint is so faded that it looks milky white in places. The motorcycle has become a standing joke among my Japanese-mounted friends. The dealer has a tough time getting parts under warranty for the bike; three weeks were consumed waiting for the mainshaft until I called BSA in Maryland and a batch mysteriously arrived that day.

The dealer is Northwood’s Tire & Cycle Service in Jacksonville, N.C. They’re great. They aren’t the biggest in the world nor do they have the best of everything but the attitude and desire of the owner, Fred Silvia, more than overcomes these shortages. He has picked up the bike twice for free at a distance of 50 miles, kept me informed of what’s going on and in general gave the BSA much better support than BSA of America has. If I didn’t have this dealer, the motorcycle would be permanently unusable. Bad marks for BSA and its product; bravo for Fred Silvia.

Alan P. Sullivan Havelock, N.C.

MUFFLER CRACKS

One month after the expiration of my warranty my 750 developed cracks along the welded seams in the mufflers. The dealer referred me to his service manager who said “Sorry.” I tried to obtain some satisfaction from American Honda in Atlanta, who referred me back to the service manager. After another “Sorry” from the service manager, I purchased another set of exhaust pipes, all four of them.

Needless to say, I’ve purchased my last Honda, thanks to American Honda and Honda of Marietta.

Henry J. Sluss Smyrna, Ga.

GETTING IT “RIGHT”

I would like to mention a few Kawasaki dealers who I have had the pleasure of dealing with. “Crossroads Cycle” in Fairfax, Va., supplied me with my new Kawasaki 500 as well as uncomplaining and fast warranty service. “Amherst Sales and Service” in Kingston, Ontario, Can., has to be one of the best dealers I have ever seen. They do excellent work and serve as a great source of friendly information. Also I think that “MotoMichel” in Quebec City, Quebec, Can., deserves special credit. I stopped by this dealer while on a trip, at lunch time, to have an ignition problem repaired. My alternator rotor had gone. The trouble was immediately repaired (during a mechanic’s lunch hour) and the work (worth about $70) was honored under a warranty that originated over a 1000 miles away in Virginia.

Now, about my bike, of which I am extremely fond, as is any cycle “nut.” I own a 1971 Kawasaki 500 which I purchased at the beginning of last summer and now have put on over 14,000 miles. I have been extremely pleased with my bike’s all-around performance and I have effected several modifications on it that may be of interest to other owners.

I initially purchased the bike because of its low price and high performance. But I found that I wanted a better handling bike. The stock 500 when banked over hard (pegs grinding) in a bumpy corner tended to wallow. It felt like the bike was flexing. The first thing I did was to drain the stock “fish oil” out of the front forks and replace it with 30W Lubri-Tech racing fork oil. Then I installed several large washers inside the front forks, on top of the springs (large enough so that they wouldn’t fall inside the springs). This allowed a stiffer pre-sprung front end that was very “tune-able” over a limited range. I played around with the tuning until I ended up with just under a 1/2-in. spacer. Along with this I installed a hydraulic steering damper, an inexpensive Kawasaki accessory.

These first two modifications made for a somewhat stiffer ride at slow speeds, but much more controllable at high speeds, particularly in bumpy corners and windy weather.

(Continued on page 38)

Continued from page 32

Next I purchased a set of the famous Koni shock absorbers along with two Girling 70/100 progressive springs. These items bolted on in place of the very poor stock rear shocks with virtually no modifications. The Konis took a little time to break in and then to “tune” to my bike. Once finished, I was amazed at the final improvement in handling.

I have yet to induce any type of wobble or flexing in any kind of corner or at any speed, since these modifications. On my favorite test road (like every cafe racer has) I had a sweeping, bumpy, high speed, left hand corner. I found that I could go through this corner up to 10 mph faster than I would have attempted before.

Having solved my bike’s handling ills (and for the low price of about $70), I started to examine ways to improve the front brake. The stock brake was adequate for normal speeds around town. But when brought up to the bike’s capable (illegal) speeds, the brake proved less than satisfactory. Under hard braking from about 100 mph, the brake would fade badly; by the time 40 mph was reached it began to feel very much like a sponge. I felt that most of this problem was due to the fact that this particular type of lining reacted adversely to heat. The solution, of course, was to cool it. I did this by venting the left side of the brake drum with six 2-in. diameter holes, with small (1/2-in.) vent through holes on the other side. The venting does not appear to affect the structural rigidity of the brake, as the majority of the strength lies in the six large internal structural “webs” that were left untouched.

The result was a definite improvement in braking. I found that I could brake hard from 100 and then lock up my front wheel at 70 with a 2-fingered tug. I was curious now to see what would happen in the rain. Before I vented the brake, I found that I had to use it constantly in the rain to keep it dry, as it was not at all waterproof. With the venting there was no noticeable difference.

The next thing I installed on my bike was a partial racing fairing. I put this on for several reasons: 1) it kept me somewhat dryer and warmer in rain and cold, while not looking as ugly (in my opinion) as a touring fairing; 2) improved gas mileage and top end; as well as, 3) improved appearance of the bike.

The fairing, of course, necessitated “low” bars. I personally prefer riding with the flat bars rather than normal high bars. I find the fairing very comfortable at high cruising speeds. It does improve gas mileage from 5 to 15 mpg at high speeds (75-85). It also appears to improve top end, although I have not been able to verify this. The fairing does not significantly affect anything until speeds in excess of 60 mph, after which the bike definitely feels a little faster, albeit part of this may be psychological. The bike is definitely much more stable after 90 mph now.

Last on the list, I mounted a Carello quartz halogen driving lamp below the fairing. Although the stock headlight is quite good, the quartz light is absolutely fantastic. I have wired it through the turn signal switch (there are no turn signals) so that I can switch from high beam to quartz beam. For riding long distances at night this light is indispensable, but illegal in some places.

I rode my bike thus equipped from my university in Ontario, Can., to my family’s place in Virginia several times last summer. I also made a 3000-mile trip with a friend (who has a 350 Honda) to the Canadian east coast. I found my bike to be an excellent touring machine and very reliable.

My only complaints lie in some rather obvious areas, all of them arising from the bike’s power. First it goes through chains and tires very rapidly, despite care. I must admit, though, that I have a very active throttle hand. And I found that the bike has a tendency to “eat” rear spokes if given full throttle on very bumpy roads. This last problem I solved by not opening the throttle on bumpy roads.

(Continued on page 40)

Continued from page 38

I feel now that I have one of the faster, better handling bikes on the road, along with the good fortune of excellent dealers.

Mark Mills Kingston, Ont., Can.

CANADIAN vs. AMERICAN

I was stranded at the Canadian-New York border with a blown piston late one Saturday afternoon. The telephone book had two cycle shops listed—one 20 miles south in New York, the other 35 miles northwest in Kingston, Ont., Can. The dealer in the U.S. laughed when I called and he flatly refused to help me. So I called Whitaker Cycle Sales and talked to the manager, Gerry Apps. He said he would be there as soon as possible. After we got my bike back to town, Gerry unsuccessfully looked for a place for me to stay. He insisted that I stay with him and his family until the cycle was fixed. Meanwhile he let me use a dirt bike he had in the shop. Gerry, an Ossa rider, is trying to stimulate some motocross activities in the Kingston area.

What could have been a crummy experience was the high point of a tour through Ontario, thanks to a Canadian Honda dealer. Honda of Canada, you are very fortunate to have someone like Mr. Apps on your side.

Mel Goldberg Allentown, Pa.

YAMAHA vs. HONDA

May I first say that “Feedback” is the best idea I’ve ever seen in any motorcycle magazine for encouraging reader participation. The opportunity to voice opinions on motorcycles in a national magazine is a precious one and should be exercised by those who wish to bring critical information to light.

I want to compare two motorcycles I’ve owned. One is a 1970 Honda CB 450. The other is a 1971 Yamaha R5B 350. Both were purchased new. Differences in acceleration and top speed are negligible. The content of my comparison will deal with reliability, ease of operation and roadability.

The Honda’s cam lobes wore down during a trip from California to Ohio last summer. I’ve heard of this problem Continued from page 40

(Continued on page 42)

with only a few 450s. They were replaced under warranty in four days. An embarrassing situation occurred when turning a corner with two up. Things would scrape. The bike was sold with 7000 miles on the odometer and these were the only complaints. Braking was excellent. So was comfort and appearance.

The Yamaha is a different kind of motorcycle. It’s fast (for a 350), handles great, and scrapes only when you drop it. Its brakes aren’t as good as those on the Honda, but they are pretty good. The R5B’s saddle is too hard. And it has to be the filthiest motorcycle I’ve ever seen. It leaks. The chain throws oil all over everything. And does it ever smoke. The rear wheel is impossible to keep clean.

Now, what about reliability? So far (and I mean “so far”), it has had three fuel petcocks, the needles and seats replaced in the carbs, 12 spark plugs (1600 miles on odometer), and a new oil pump. The oil pump cured a problem that lasted the first two months of ownership: it wouldn’t start in the

morning. I still can’t get the handlebars locked. It seems like they gave me the wrong key or something. It also has a rougher ride than the Honda.

Which motorcycle was the most pleasant to own? Without a doubt, the Honda. Its superior reliability, brakes and comfort make it worth the extra money.

Rick Tomaine Garden Grove, Calif.

CHEWING GUM?

When I get about twenty thousand on my Honda CB 350 I’ll let you know how it held up. I only have 2700 on it now and so far so good. I did have a little trouble with a leaky head gasket. It didn’t hurt anything but the oil looked rather messy all over the left side of the engine. The dealer here in Corvallis fixed it on the warranty without any hassle. Maybe he stuffed some chewing gum in there, I don’t know, but it doesn’t leak any more.

Sam Herr Corvallis, Ore.

UNHAPPY R75/5

I have recently purchased a ’71 R75/5 BMW which has developed some rather annoying problems. The most serious of the problems involves the Bing carburetors. Having talked to several 75 owners in this area, it appears as though the problems are quite common: 1) Although I’ve invested much time and money at the dealer’s, it has been impossible to obtain a consistent idle (the idle usually sticks at 1500-2000 rpm or it stalls); 2) when accelerating from start or gear changes the engine sputters and pauses before it finally responds; 3) when decelerating or shifting down it takes 10 seconds or more for the engine rpms to drop. The mechanics I’ve talked to agree that this is a characteristic of Bing carburetors and one must live with it—this does not in any way agree with the advertised philosophy of the BMW Company.

(Continued on page 44)

Continued from page 42

In the more nit-picky department, I’ve encountered several other “annoying” problems: 1) the electric starter

rarely works; 2) the speedo-tach accumulates so much water on damp days that it is hard to read; 3) the battery straps split the first month I owned the bike, as have all the rubber dust covers; 4) oil leaks abound at almost every gasket; 5) paint on the gas tank looks like someone poured it on with a can.

Many of these last items are of minor consequence but I think they indicate a poor inspection system or no inspection at all at the factory. This is disappointing, considering the reputation and initial cost of the bike, I, like most BMW owners, paid the $1900+ price because we were buying one of the best touring motorcycles made, a reputation well deserved in previous models. Many of the 75 owners, myself included, question whether the philosophy of the dependable bike was carried over to the R75/5. Maybe other 75 owners have solved the major problems of the carburetor adjustment and wouldn’t mind passing it along to the rest of us sputtering souls.

W.R. Fagerberg Tampa, Fla.

RISER BAR PROBLEM

A little item for your reader-cautioning efforts—a while back I purchased a higher-rise handlebar for my Honda CB350. To use the standard Honda controls and wire routing, it is necessary to cut a roughly oval-shaped hole in the lower surface of the center portion of the handlebar to carry the wiring from inside the bars into the headlight assembly.

I cut this hole fairly carefully, to about the same dimensions as the hole in the standard Honda handlebar. I filed the edges of the hole to give a smooth, non-chafing edge against which the wiring harness sheath rides.

The other day, after about 15,000 miles of mostly high speed (around 7000 rpm in fifth, or 70 mph) cruising, the handlebar broke in half while coming to a stop. Examination of the bar showed rather odd, rusty fatigue cracks running around the circumference of the tubing at the ends of the hole which I cut for the wiring harness. The apparent age of the cracks suggests a long term, gradual failure due to vibration. The bar was mounted in the standard Honda rubber mounts.

It would be a good idea if you and/or your colleagues cautioned Honda owners about making similar installations of handlebars. Unless the bars have the heavy center reinforcement section that is incorporated into the standard CB350 bar, I strongly suggest that outside-the-tubing wiring be used. Failure of the center of the handlebar allows the ends of the bar to swing forward and toward the center of the headlight, the Honda handlebar mounts pivoting freely unless connected to each other by a solid bar. The consequences of this happening at any speed, traveling down the road, should be plainly terrifying. A serious crash almost certainly would occur, since failure would be most likely to occur when the machine was being braked and the rider’s weight was transferring forward against the handlebar.

I don’t think that the handlebar which I purchased was better or worse than the typical aftermarket bar. The rise was moderate but higher than the Honda bar and subsequently more comfortable either in town or riding behind a fairing. The bar was a simple, onepiece bent tube, chromed. It is my opinion, based on hindsight, that the wire routing hole cut into the center of the bar, combined with the rubberisolated Honda mounts, creates an intolerable environment for any bar not fitted with a very substantial center reinforcement or doubler. Look at a standard Honda handlebar to see what seems to be required.

Jon S. McKibben Marina del Rey, Calif.

Of interest to readers: McKibben is the man selected by Honda to pilot the Honda streamliner in search of a new absolute two-wheel speed record.— Ed.

9200-MILE HONDA 4

After something over 9200 miles on my 1970 Honda CB750, I think I can make a few observations of interest. On the positive side, it has good power and torque at speeds above 5000 rpm, and passable torque down to 2500. The ride is pretty good, if the rider is fairly heavy. With a passenger and luggage, the ride is really good. The gas mileage is exceptional for a bike this size. I averaged 52 mpg on a 2400-mile trip last summer. My 40-in. BSA will barely match that, even with a full Avonaire fairing. Although the beast is rumored to require quite a bit of tuning, I’ve not found that to be the case. I do adjust the carbs with every service operation though little change is normally required. The engine is also quite smooth, and the brakes are the best I’ve seen on a big bike.

On the negative side, the weight and high center of gravity definitely reduce rider confidence on winding roads. I’m not sure that it corners much more slowly than the 40and 45-in. English roadsters, but the integrated bike/rider feeling just doesn’t seem to be there. While on this particular comparison, the gearbox on my BSA shifts much more smoothly and quietly, though the Honda is not really objectionable.

As far as practical tips to other riders are concerned, I guess I’ve got three. First of all, throw the KLG plugs away and put in Champion R-6s. The KLGs develop a high speed miss, which can’t be detected visually since they look alright after a run. Secondly, replace the original equipment chain when it wears out with an American Diamond. My original chain wore out in 4200 miles, despite continual adjustment and external lubrication. The adjustment had been taken up more than four marks on the swinging arm at removal. After over 5000 miles on the American Diamond replacement, adjustment has been taken up less than one mark. I just completed a weekend 550 miler, with no lube or adjustment, and the thing returned almost as tight as it left. And lastly, the carbs may be adjusted reasonably satisfactorily by using two dowel pins. I set the slides at idle so that they’ll barely accept a 3/32-in. dowel pin. Then, locking the slides in a partially open position with the throttle damper, adjust one of the end carbs with the twistgrip, so that it will just accept a 0.25-in. dowel pin. After tightening the throttle damper quite securely, adjust each of the carbs in turn so that the dowel pin will just fit into the slide cutout, maintaining the originally adjusted slide for reference. The accuracy of adjustment is probably not so good as that done with pressure gauges, but I’ve found it effective.

Mike Stephenson

Livermore, Calif.

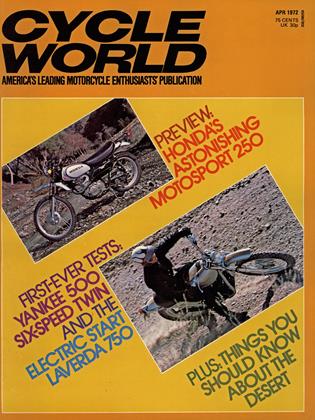

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

April 1972 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1972 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Dept

April 1972 By Jody Nicholas -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

April 1972 By Ivan J. Wagar -

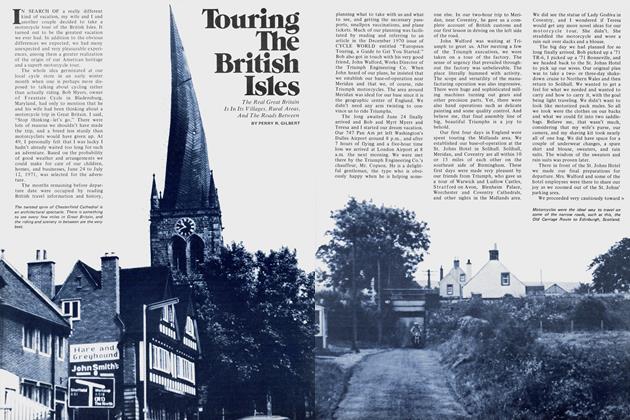

Features

FeaturesTouring the British Isles

April 1972 By Perry R. Gilbert -

Technical, Etc.

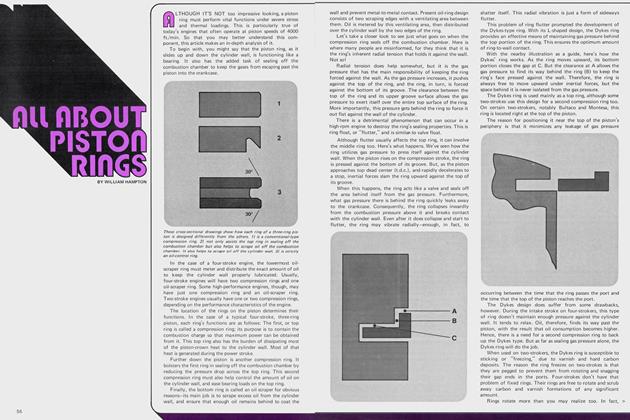

Technical, Etc.All About Piston Rings

April 1972 By William Hampton