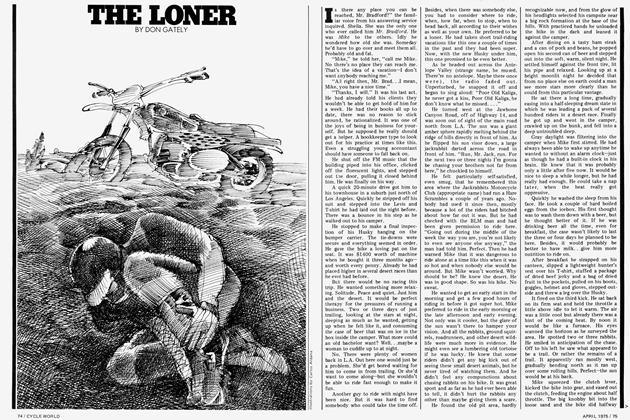

YOUR FIRST RACE: THE NOVICE

What is it Like to Race Through the Sand Washes and Puckerbushes? Join This Rider and See For Yourself

Don Gately

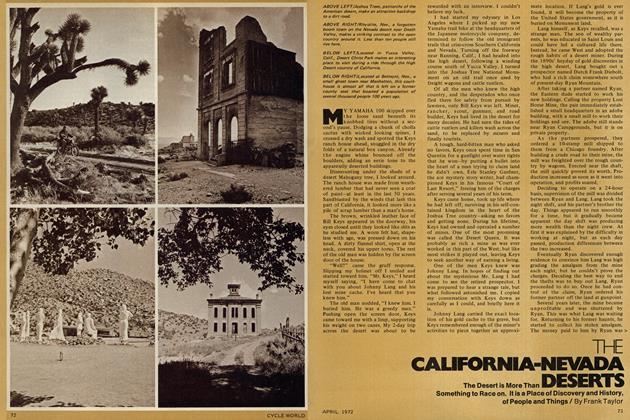

PAUL MARTIN gazed out at the brown, lifeless desert around them. The desert was ringed with equally brown and lifeless-looking mountains. They looked so close that you should be able to walk to them in a half hour. Yet Paul judged them to be at least 20 miles away. Their first view of California. Disappointing. He thought of the green New England woods they had left 3000 miles back.

“Looks pretty bleak,” he said to his wife, Mary.

“Maybe it’s just the time of year,” she said hopefully.

“Yeah. Anyway we’re still about 300 miles from Los Angeles. Let’s not judge all of California by what’s here.”

From the back seat, Mike, a frecklefaced boy of six, made his presence known: “Daddy, can we have an ice cream?” He was acting as spokesman for his sister, Sharon, a year and a half younger.

“We’ll get you one when we come to the next town, Mike. But it may be quite a ways so you’ll just have to be patient.” He knew the kids were hot and dry. He was just grateful that the air conditioning was doing its work well and that their 3-year-old station wagon hadn’t overheated yet. Crossing the Colorado River into California he had noticed a large number of cars were pulled to the shoulder of the road, their hoods raised and steam billowing out. When they passed through Needles the temperature in lights outside a bank had been 115. He had taken the precaution of buying a desert water bag to hang on his front bumper. Now he kept his fingers crossed that they wouldn’t have to use it.

“I wonder if this is the kind of country they have the hare ’n hounds in,” he said to Mary.

“Hare and what?”

“Hound. Hare ’n hound. You remember me telling you about the crosscountry motorcycle races they have out here in California. Like we saw on television.”

“Oh sure. How could I forget? Are you still wanting to get involved with motorcycles again, then?”

“You bet. Look, sweetheart, I had a bike when we got married, remember. And I sold it when Mike was due because we needed money for him and the nursery and all of that. But now, with the company giving me a big raise to transfer out here, I think I can afford it again.”

“Just don’t forget that we are going to have some big expenses getting settled into a house, getting furniture, a second car for me and who knows what all else.”

“Well, maybe I won’t get one right away. But as soon as possible.”

“I thought you had long since gotten all of that out of your system. I mean after all, Paul, you’re 33 now.”

“I don’t know that I’ll ever completely get bikes out of my system. Anyway, 33 isn’t exactly an old man, you know.”

It was a couple of months later that Paul started shopping for a bike. After visiting several shops he returned to the one nearest his home. They had seemed like a friendly bunch in there and he figured if he was going to get involved in desert racing he would need more than just a bike. He would also need advice.

“Hi,” the dealer smiled at him, “I see you’re back.”

“Yeah, I guess I am,” Paul returned his smile. “Like I told you before, I rode bikes for several years back east. Mostly street, but I did a little woods riding, too. Now I want to get into this desert racing.”

“You came to the right place. I’d suggest this 250. It’s not too temperamental, so you can use it for just going trailing or even riding around the neighborhood in the evenings. Then when you get ready for some serious racing you bring it back in and we’ll get it set up properly.”

“I dunno about a 250. Seems awfully small. I always rode the 40-inchers before.”

“How long ago was that?”

“Oh, seven, eight years ago.”

“Well, things have changed a lot since then. The 250s today are a far cry from what they were then. In fact, if you do get a big bike, I guarantee you’ll not be able to go as fast on it as you can on this 250. And it’ll cost you more, besides. I’m sure you could even get by with less than a 250 right now. But pretty soon you would master a smaller bike and want more power. No, this is the best choice for you.”

The first couple of weeks that Paul owned the bike he just rode it around the neighborhood. Then he went out to the desert on a Sunday with another rider who worked where he did. They left early in the morning, taking a cooler of beer, Gatorade, sandwiches, potato chips and cookies. Paul felt eager, even excited. As the sun came up they were already 50 miles north of Los Angeles. Paul noticed that the desert wasn’t quite as brown and barren here as it was where they entered California. There was more vegetation. Greasewood bushes, Joshua trees and Yuccas were more evident. Amidst the brown there was green. Still, the overall impression was one of vastness, openess, of a hard land, a land that survived with almost no water.

As if reading his thoughts, his friend, Jack, said: “There it is, the Mojave Desert. Like one great huge playground for motorcyclists. Or it once was. Not near as much of it left to ride on as there was just a few years ago. And it looks like we’ll be losing more of it. It’s the ecology thing that everyone is so worried about. I don’t think the bikes do much damage to the desert. I think it’s the noise thing that mostly irritates people.”

Depressed by the trend the conversation was taking, Paul changed the subject: “Is there much animal life on the desert? It looks so dry you wouldn’t think it would support much.”

“Oh, you bet there is. Plenty of life. Zillions of rabbits. More of them than most anything else, I guess. And all kinds of little ground squirrels, field mice and the like. And there’s coyotes, tortoises, roadrunners. And when you get up into the mountains there’s deer.”

Paul noticed that most of the traffic was other motorcyclists with bikes in pick-ups, vans, on campers, trailers. And most had number plates. “I guess there •is a race someplace today,” he said.

“There is at least one race most every Sunday,” Jack answered.

“Well, this must be a big one judging from the number of bikes.”

“Maybe. But even the small ones get 4 or 500 entries.”

After they had unloaded the bikes, had sandwiches, and warmed the engines, it was finally time to go. Paul followed Jack, staying a distance behind so as to avoid the dust he was kicking > up. He rode gingerly at first. The sand seemed very difficult to steer through. His off-road experience back East had mostly been on hard-packed earth. He had encountered a little mud in those days, but had avoided it when possible. Now he felt stiff, rigid. He knew he had to master it to the point where he could relax. Up ahead Jack had stopped and was waiting for him. He came abreast and stopped.

Continued from page 83

“When you get in this deep sand, Paul, you’ve got to turn it on. The faster you go, the easier it is. Sit back on the end of your seat. That way you’ll get more traction. Don’t hold on to the bars so tight, you’ll wear yourself out. Just screw it on and let the bike pick its way. Don’t try to steer it, just kind of guide it.”

Paul concentrated on doing the things that Jack had told him. And as the day wore on he found himself becoming more proficient. Still he found the sandy washes the hardest part of desert riding. Fortunately for him, only about 20% of the terrain seemed to be sand washes. He was surprised when Jack told him that lots of racers preferred the washes, that they considered them a place where they could sit back and relax. “Like riding a freeway,” he said.

Later in the afternoon, Jack took him into a narrower wash where the sand wasn’t very deep but the banks were high. He saw Jack ride high up one bank and then drop back into the wash and go high up the other side as the wash curved. He continued to do this, putting his centrifugal force to work for him. Paul tried it—and fell down. He picked his bike up and found that it now had a tweaked set of handlebars. He had bruised his knee on a rock, but other than that he seemed to be all right. Jack returned.

“What happened, tiger?”

“I was just trying to ride the banks like you were doing and I unloaded.”

“Don’t be discouraged—it happens to everybody. You know what they say— there are only two kinds of riders—those that have fallen and those that are going to. What you were probably doing wrong was going too slow. In order to get up high on these banks, you rely on your speed and momentum to carry you through to the next turn.”

Paul had never lacked for guts. He tried it again, this time hitting the banks harder and faster, the way Jack had suggested. When he got used to it he found it was like riding a roller coaster-tremendous fun.

It was after dark when they reached Paul’s house. While they were unloading his bike, Mary came out to meet them.

“Did you have a good time?” she asked.

“Fantastic,” Paul replied.

While he was showering he began to realize that he was very tired. And that he was stiff. His bruised knee ached. His lips were chapped. His hands had blistered. Guess I’ll have to get in shape, he told himself.

During the next couple of months Paul began to exercise. He would run in the mornings before he went to work. At first he was out of breath and his legs ached before he made it around the block one time. But gradually he was able to go farther and farther. When he reached a mile and a half he quit going any farther. About three mornings a week he would make that run. He bought a set of barbells and worked out two or three times a week.

One night a week he would spend as much time as necessary working on his bike. He would clean the air filter, adjust and oil the chain, check the sparkplug, and look for anything that might have vibrated loose.

Every Sunday he went riding, sometimes with Jack, sometimes with other riders he had met at the shop or in his neighborhood. He rode in different areas each time. He knew that he was making steady improvement. Now he had no trouble staying up with Jack, and he found that he rode faster than many of the riders he went with. He felt he was finally ready for desert racing.

He went back to the shop and informed them he was ready to race. They suggested a few changes that would be desirable: A number plate would be put on and the lights would come off. A compression release would be added. And a fork brace. And a holder for extra plugs should be mounted to the frame. Better handgrips would help to stop the blisters. A hop-up kit with an expansion chamber would give him more power. Paul okayed the suggestions. A week later he went back and picked up his bike.

That Sunday he got up at 4:30 in the morning. He donned long underwear, heavy socks, Levis, a sweatshirt and Levi jacket. He pulled on his new lace-up boots, washed his face and went to the kitchen for a bowl of cereal and a quick cup of coffee. He grabbed his helmet, goggles, gloves and kidney belt and went out to the garage. The cold air caused an involuntary shiver. He rolled the bike out of the garage, parked it and went back for his gas can. He locked the garage and returned to his bike just as Jack arrived.

They had no sooner gotten on the road than he told Jack to stop at the first open gas station—he had to go. After a few miles they found one and stopped. In a few minutes they were on the road again.

Jack explained what to expect: “This race we are going to is a hare scrambles.

That means we will run over the same loop twice. It is a 50-mile course so we’ll have to stop for gas between the loops. When we get there we have to find the sign-up table. You’ll get a pie plate which we’ll have to tape over your number plate since you don’t have a desert number yet. Then, when the race starts, we’ll be lined up abreast with all of the other guys. We’ll be facing a smoke bomb. Everyone will have their engines off. A banner will be raised and then dropped. When it drops you crank your bike and take off for the bomb. Got it?”

“I got it. And Jack...would you mind stopping at the next station—I’ve got to go again.”

“Sure. Lot’s of guys get the runs before a race. And butterflies. Nervous stomach. It’s all the same thing. A top desert racer once told me that he gets ’em too. He said if you don’t get the old butterflies you’re really not out there to race.”

As dawn grew into early morning, Paul saw that there was a steady flow of traffic, all trucks with two or three motorcycles in them, headed north. As they passed through the town of Mojave, Jack said they should begin looking for the lime marks along the highway which would guide them to the location of the race. After a short distance they saw the first mark. They followed it for 10 or 12 miles. Sometimes they would go a couple of miles without seeing any marks and Paul would become apprehensive that they had missed the turn-off and gone too far. But he saw all of the other trucks in front and behind them and realized that his fears were silly. Finally they came to three lines of lime and saw the trucks turning in to a dirt road leading out across the desert. Gazing out on the horizon he saw a dark funnel of smoke.

“Are they holding some kind of race this early?”

“No,” Jack answered, “They light the smoke bomb early so that the guys who are there already can ride out and check the course between the start and the smokebomb.”

“How far is that?”

“Usually about three miles.”

“Can they ride beyond the smoke to practice on the course if they want to?”

“No, that's against the rules. Anyone that gets caught doing that is disqualified. But lots of guys came out yesterday and rode the whole area out here. ’Course they weren’t supposed to ride the course then either. But it’s pretty hard to stop it. The sponsoring club is busy marking the course and making all kinds of final preparations. But it is a good idea to come out here the day before if you have a camper and the time. It is always good to be able to get the feel of your bike and the dirt as much as possible before the race. A half day of practice before a race can make a big difference. But a good night’s sleep is also essential and if you don’t have a good warm camper, forget it.”

(Continued on page 104)

Continued from page 84

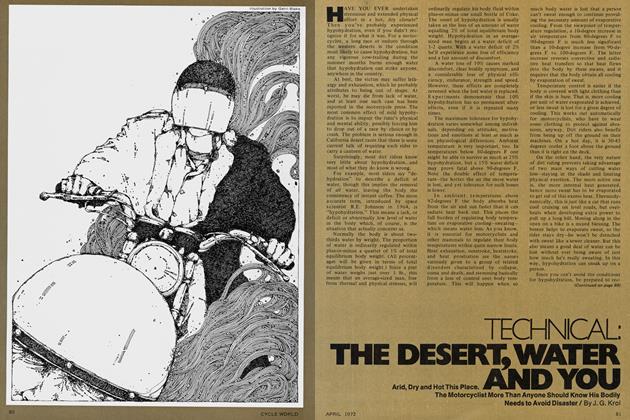

As they were bouncing along the dirt road behind the caravan of trucks Paul noticed that the dust was so thick he could hardly see the truck directly in front of them. “If it’s this dusty on the course, how in the hell will we ever see where we are going?” he asked.

“This is nothing. It rained a couple of days ago. It really shouldn’t be too bad. You should see it in the summer. Sometimes it gets up to a 110 or 15 and the dust is so thick you can cut it with a knife. Times like that it’s pretty rough. Can’t see more than a few feet.”

“So how do you race, then?”

“I dunno, you just do. Got to love it, I guess. ’Course the farther towards the front of the pack you get the better—if you can. ’Cause then you have just that many fewer guys’ dust to eat. And you try to get on the upwind side of the course so the wind is blowing away from you.”

“What if the wind isn’t blowing?” “The wind is always blowing on the desert. Ninety percent of the time, anyway.”

“Anything else you can tell me that I ought to know?”

“Oh, I dunno. Some of the guys wear wetted-down neckerchiefs around their faces like the outlaws in the old westerns. Keeps the dust out of their throats. And a canteen of water or Gatorade is a good thing to have along. And of course you already know about having a tool kit, extra plugs, a master link and some extra chain links along. Let’s see.... Don’t try to win the race right away. Get to the smoke bomb as quickly as you can because you don’t want to eat any more guys’ dust than you have to. But after that, try to pace yourself. Ride hard, but not as hard as you can. Remember, you’ve got 100 miles to go.”

They were approaching the pit area now. Paul saw before him what looked like an overnight town. Campers and trucks were parked in clusters stretching out in three directions from the intersection with another dirt “road” they were almost to. In three or four spots there were portable johns. People were lined up in front of each of them. People were standing around fires and portable heaters. Some were having breakfast. Newer arrivals were unloading bikes. Riders were making last minute checks and repairs on their machines. Many riders were zipping up and down the roads. There was a deafening cacophony of sound.

Jack pulled up to a couple of club members passing out paper bags for trash, and envelopes with instructions. He tried to ask the one who handed these articles to him where the Desert Hares were camped. The man shouted back that he didn’t know but that they should look for a sign or the club’s banner.

Jack pulled to the side to let the trucks behind them proceed. There were many arrow signs on stakes driven into the soft sand pointing down one of the three directions of the intersection. Jack spotted the sign he wanted and made the appropriate turn. Paul saw a big crowd of riders gathered in front of a card table outside a camper. A couple of men sat at the table and checked the riders’ entry blanks and a line was formed outside the camper where the riders were paying their entry fees to a couple of wives of the sponsoring club. “Sign-in,” Jack shouted, pointing. As they drove past the pit areas of the various clubs Paul was intrigued by the banners and the jumpers that the riders wore: Checkers, Shamrocks, Antelope Ramblers, Viewfinders, Rams, Invaders, Victors, San Gabriel Valley. Aren’t there any riders who don’t belong to clubs besides us, he thought.

(Continued on page 110)

Continued from page 104

Jack spotted the camp of the Desert Hares and wheeled in. He looked around for the couple of members he knew, but didn’t see them. They got out and began unloading the bikes. The air was still cold and the wind was blowing. But the sun was shining from a cloudless sky. It would be warm in a couple of hours, but Paul was glad he had worn his longjohns.

Their bikes started after just a few kicks. They sat warming the engines. Paul was glad he had checked his bike over carefully during the week. After a couple of minutes Jack signalled that they should go to the sign-in area. They rode slowly in second gear, getting the feel of the bikes and the dirt. Small kids on minibikes, wives and girlfriends on trailbikes and other racers warming their bikes were going by them in what seemed to be all directions.

As he waited in line to turn in the entry blank he had filled out, Paul read the paper they had given him when he and Jack arrived. It talked about keeping the desert clean, being disqualified if you cut the course, the trophy presentation. And it said there would be a riders’ meeting at 9:30. Paul looked at his watch: 9:15. “There’s a riders’ meeting in fifteen minutes,” he said to Jack, raising his voice to be heard over the passing bikes.

“Forget it,” Jack said in a loud voice, “you can’t hear what’s being said, anyway. They just tell you that three lines mean danger and to stay on the course if you break down so that the clean-up crew will find you. And they tell you what the course is like. We’ll find that out soon enough, anyway.”

After paying his fees, Paul was given a paper pie plate with a number marked on it in grease pencil and a large piece of cardboard with the same number on it. Jack told him to take a few strips of masking tape from several rolls hanging from nails on the back of a trailer. They walked over to the bikes and Jack helped him tape the pie plate over the regular number plate his dealer had sold him. Then they taped the cardboard across his gas tank, number side down.

“What’s this for?” he wanted to know.

“For checkpoints. They’ll have two or three checkpoints. That’s something else they tell you at the riders’ meeting. Anyway, at these checkpoints they mark your card with different colored crayons. Shows you made the whole course.”

They went back to the truck, taped Jack’s card to his tank, topped their gas tanks off, put their watches and wallets inside the truck and locked it up. They put on kidney belts, goggles, helmets, and finally gloves. They still had 15 minutes before they were due at the starting line. Jack’s friends in the Desert Hares were nowhere to be seen. “Come on,” Jack shouted, “let’s ride ’til time to go to the line.”

“Thanks,” Paul said, “but I’ve got other ideas. I’m going to visit the little house one more time before the race.”

“Okay, guy,” Jack laughed, “Good luck. I’ll see you after the race. And remember, if either of us doesn’t show up within a reasonable time after the race is over, the other one takes the rope and starts over the course backward.” He rode off.

When Paul finished his business he rode over to the starting line. His first impression was one of utter confusion. There were roughly two lines, experts and juniors in front and novices in the rear. But they were only a semblance of lines. Riders were going back and forth in front of, between, and behind the lines. A few photographers, wives, wellwishers and hangers-on were mixed in the crowd. He couldn’t spot Jack.

He was lined up in the second row, almost elbow to elbow with a couple of other riders, but the noise made conversation impossible. He noticed a member of the sponsoring club going from bike to bike in the front row with a rubber stamp and pad, stamping the tank cards to show that the riders had started where they were supposed to. This went on for awhile, and then another club member rode past the line indicating with a slicing motion at his throat that they were to kill their engines. Gradually the bikes were shut off until the only noise was a trailbike nearby. Tension hung in the air like a rain-heavy cloud. The riders raised their legs to their kickstarters, poised for action. About a quarter mile out a pick-up was parked perpendicular to the line. A small group of people were standing in the truck. Slowly they raised a large, bright banner. For maybe thirty seconds everyone seemed to hold their breath, then the banner dropped, the riders kicked their machines to life and leapt forward. As they raced toward the column of smoke Paul could see them artfully dodging greasewood bushes and picking up, or making, trails. A spiral of dust rose in a rooster-tail behind each bike and the dust converged into one dense cloud. Looking to his right, then to his left, Paul saw that the line of riders must have been a half-mile wide.

When they had seen the start, the novices, about three times greater than the group that had just left, cranked their bikes up and rode the 10 ft. to the line the others had just vacated. They sat there revving their engines. The wives and photographers of this group moved in. Several riders lined up directly behind a large greasewood bush, parked their machines and began flattening out the bush. Presumably they were going to ride over it because there were no other open spots available on the starting line-which was now about a mile wide. Paul looked at the bike next to him. An extra plug was mounted in the head so that the rider could switch without having to change plugs. And strapped to his frame was a sparkplug holder with three extra plugs. Wow, Paul thought, he’s got five plugs for a single cylinder bike. I hope the one extra plug I have with me will be all that I need. And while I’m hoping, I may as well hope that I don’t even need that.

The guy came by and stamped Paul’s tank. Riders kept firing their bikes up and gunning them, warming them for the race. Paul kicked his machine once and it didn’t start, twice and nothing, three times, and he began to panic, and then on the fourth kick it started. He let it run at little more than an idle, not wanting to use too much gas. He had a small tank and he wasn’t sure he would make the full 50 miles without running out.

(Continued on page 114)

Less Sound More Ground

Continued from page 111

Now the rider passed them, making the gesture to stop the engines. Paul did so at once. He noticed that several riders near him kept their bikes running. Another rider passed, repeating the killyour-engine signal. Gradually the bikes were shut off. Paul had an uncomfortable feeling in his stomach. Butterflies. He wanted to go to the bathroom. Almost all of the bikes were stilled now. Then somebody down the line started his. The guy next to Paul cursed. “It never fails,” he said, “every race there is some moron that has to start his bike when everyone is waiting for the banner.”

Finally all of the bikes were quiet. Everyone had their kickstarters ready. The banner came up. Paul’s throat was as dry as a tomb. If I’m thirsty now, he thought, what will I be after 45 miles? It seemed like the banner had been up for five minutes. He wondered why they only kept it up for a half minute for the experts and now kept it up so long for the novices. Then it dropped.

Paul kicked his bike over and it didn’t start. Now he felt utter frustration as the others around him were already accelerating away. He kicked again. Nothing. He choked it and cranked. It sprang to life. He grabbed a handful and dropped the clutch. He saw what seemed like hundreds of riders in front of him. But he was already passing riders—a very satisfying experience. With his peripheral vision he saw that there were still many riders behind him or no farther out. Automatically he shifted through to third gear. He estimated he was running about 40. The cloud of dust had settled on him and he could not see more than 15 ft. He tried to sit down but kept hitting ruts, bumps, and going over bushes. He found that he was standing more than sitting. He was still passing other riders, although not as frequently now. Occasionally a guy would go rocketing past him, perhaps 20 mph faster than he was running—evidently a real hotshoe who couldn’t get his bike started or had some problem that had delayed him. He had no idea where the smoke bomb was or which way the course went. But through the thick dust he could make out shapes of other riders and, sometimes, their bright colored club vests. If he was off the course, he wasn’t the only one.

(Continued on page 124)

Continued from page 114

Suddenly, as if out of nowhere, a rider was down directly in front of him! He hit his rear brake, sliding, trying to avoid the rider. Almost made it—but not quite. He hit the other bike’s rear wheel. By now he wasn’t going too fast. As he fell his leg was caught between the two machines. Quickly he scrambled trying to get out from between the two bikes. Other bikes were speeding past on both sides. I hope another one doesn’t hit us, he thought. The other rider was off his bike now and lifted Paul’s bike enough for him to free his leg. He hardly looked at the other rider. No time. He kicked his bike and was pleased that it started right away.

He had lost no more than a minute in the spill. His bike seemed okay except for tweaked handlebars. But now he saw that he was repassing many of the riders he had passed before. Soon he emerged into a small area where the dust seemed to have lifted a bit, and there was the smokebomb. A group of 20 or so were shouting at him and waving him on vigorously. He felt encouraged. He followed the riders ahead and soon found that the wide open expanse they had been riding on prior to the smokebomb had narrowed into a trail winding into a gorge. The trail was only wide enough for single file riding. On either side were big boulders and bushes. Soon the pace slackened. Paul was anxious to go faster, but saw no openings. At least the dust here was not so bad. Just for an instant he raised his left hand from the bars and wiped the dust from his goggles. It helped him see, but he hit a rough spot on the trail, bobbled and nearly lost it.

After a couple of miles of the single file trail, during which a couple of faster riders had come by him where he would have sworn there wasn’t room for two bikes, the trail widened and made a right turn. There was a large, steep hill right in front. All over the hill riders were stuck. Some were sideways. Some had the rear wheel dug in several inches. Others were off their bikes, pushing, gunning their engines, working their clutches feverishly. Some riders were going off to each side of the hill, looking for a way around it. The riders in front of Paul were stopping, analyzing the hill, trying to figure the best approach.

This is it, Paul told himself. The hill Jack warned they might have—to separate the men from the boys. If I stop and look at it, I may never make it. He had been running in second gear. Now he whacked it on, shifted into third and kept it really buzzing. He was blasting past all of the riders who were hesitating. At the base of the hill there was a small ditch which he hadn’t seen. He hit it hard and the impact threw him up over the handlebars. But he hung on, surprised, came back down on the seat and kept going. The dust was so thick on the hill from spinning knobbies that he couldn’t see the top. He stood on the pegs, leaning forward so that as much weight as possible would be off the rear wheel. He kept it buzzing, finding a path between the stuck riders as he went.

(Continued on page 139)

Continued from page 124

About halfway up the hill he began to run out of power. He down shifted to second and kept it hard on. He made it a little further, then had to slow to avoid a rider who was sliding backward across the hill. He punched it into first and the bike made another 20 ft. before the back wheel dug into the powder and began to spin. He jumped from the bike and began pushing, working the clutch with the throttle full on. He could see the top of the hill now. It was only about 50 ft. more. But he was gasping for breath. The smoke and dust was choking him. He was roasting in his underwear. Don’t stop now, he told himself. He dug his slipping boots deeper into the silt and pushed harder. Somehow he made it to the top. He got back on his bike and sat there for a full minute trying to catch his breath. He didn’t look back. He knew that this was the hardest test he would face. And he had passed it. He started down the hill on the other side. He saw that at the bottom of the hill a checkpoint, the first one, had been set up. If anyone did find a way around the hill, they would miss the check and be disqualified. Somehow he found this knowledge gratifying. He slid into the check and one of the four men with crayons in their hands quickly marked a slash on his tank card. “Go!,” he shouted, slapping Paul on the shoulder. God, this is really neat, Paul thought, now breathing nearly normally again. He quickly wiped the dust from his goggles as he accelerated down the trail. Then he stole a glance behind him. The nearest rider was a good way back, just pulling out of the check. Up ahead he saw that the next group of riders was perhaps a quarter of a mile ahead of him. The trail was relatively firm and even here. He punched into fourth. He was riding hard now, but he didn’t seem to be gaining on the riders ahead of him.

But his “rest” didn’t last long. Soon he came into a section that was full of “whoop-de-dos”—small jumps about 10 ft. apart. And to make it more difficult, the ground was a soft, beige desert sand. It would have been fun for a short distance, but the course was like this for several miles. He had to stand up a lot, and he found that his legs were tiring. A couple of the riders who had been following him came by him. They were off the main trail about 20 ft. Paul moved over but found the terrain there was no easier to navigate. So he moved back to the main trail. Gradually he was catching the next rider ahead of him. When he got close enough to see the rider’s jersey he saw that it wasn’t a man, but a “Desert Daisy.” He was chagrined. Here he had been working so hard in what he considered a strictly man’s sport, and here was a girl. And judging by what he could see, a slim, pretty girl. Riding a 100cc Hodaka. He resolved to try harder. Gradually, he pulled away. Big deal, he thought, a 250 against a 100.

(Continued on page 140)

Continued from page 139

Up ahead the course turned into a wide, deep sand wash. He knew lots of riders that hated this kind of terrain. Thanks to the training Jack had given him, this was a welcome chance to rest. He sat back as far on the seat as he could, got “up” on top of the sand in a planeing action, and gradually was able to shift through to top gear. It ran for almost five miles, curving every hundred yards or so. For the first time he began to see broken-down riders on the course. Every now and then he would pass one at the edge of the wash, his bike leaned against a bush. Sometimes they would wave. Others were evidently sleeping, knowing they would be there for quite awhile until somebody could come to their rescue after the race.

At the end of the wash Paul came to the second checkpoint. By now the riders were spread out so that a group was a couple of hundred yards ahead of him and another group a couple of hundred yards behind him. But while he was having his card marked, a Bultaco came sliding in behind him. Paul wondered why he hadn’t seen him. Did he cut the course? Was he simply riding slightly off the main trail where the ground might be harder? Paul didn’t have time to speculate—the rider was passing him. Oh no you don’t, Paul thought. The trail was narrowing into an ideal desert trail—hard packed with frequent small hills and just enough rocks and turns to be interesting.

Paul caught the Bui rider and passed him. For the next mile he could hear the Bui right on his tail. He rode as hard as he could. Then the trail split for a short distance. Paul went to the right, the other rider to the left. When the two forks converged again the other man was there a hair ahead of Paul. The two diced back and forth all the way to the next checkpoint. The adrenalin was flowing and Paul thought: this is it, this is why I went to all of this trouble. Just me and this guy I don’t know, out here in the middle of nowhere busting our tails to pass each other.

But at the next check, his fun was over. As he slid in for the crayon check, his bike conked out. He pushed it off the trail and began cranking. No luck. He undid the wing nut on his plug holder, removed the plug wrench and unscrewed the hot plug. Looking at it he saw that it had whiskered, or bridged as the riders called it, when a grain of dirt sucked through to the plug electrode. He slipped it out of the plug wrench on to the seat. Then he unscrewed one of the extra plugs from the holder and screwed it into the cylinder head. He picked the plug up. It burned through his glove and he gingerly jiggled it around and managed to get it back into the holder. All the while other bikes had been passing him. He’d catch them. But that guy on the Bui was probably so far ahead by now that he would never see him again.

And that’s the way it happened. It was another eight miles, mostly sand washes with one steep downhill before the pits. He caught most of the bikes that had passed him during the couple of minutes it took to change the plug. But that was too much to give the Bultaco rider. As he came into the pits he saw that all of the clubs’ pit crews had lined up right alongside the course. The Desert Hares were there, but he and Jack hadn’t arranged to have them bring their gasoline and Gatorade with them. He would have to go to their truck. He made a wrong turn and lost a couple of minutes before he found the truck. He pulled in and pulled in his compression release to kill the engine. He pulled off his gloves and pulled his goggles over his helmet. Quickly he found the Gatorade in the cooler and took a long deep drink. Then he grabbed his gas can and a funnel, unscrewed his tank cap and filled it. He took another shot of the Gatorade, pulled his goggles back over his eyes, wiped them with his bare hand, pulled his gloves back on, cranked the bike and took off. The whole thing couldn’t have taken more than 3 or 4 minutes. But if he had arranged to have the club have his gas right on the course....

As he rode back on to the course he realized that there were a good many spectators watching him. The club members were pointing in the direction of the course and signaling him to go. He knew he was tired and starting to get stiff, but there was quite a kick in having all of these people watching him. He screwed it on even harder than usual, lofting the front end over the small jumps and sliding through the turns. But soon the glory was over. He was back out on the trail—totally alone. Now, for the first time, he had to pay close attention to where the trail went. There was nobody up ahead to follow. After a time he looked back. He saw no one. He had the strange sensation of being the only one still in the race. Or of being lost. But every once in awhile he would come across a broken-down rider to remind him that he was indeed not alone, and was still on the course and in a race.

(Continued on page 142)

Continued from page 141

For the first half of the second loop he rode faster than at any other time during the race. Since there was very little traffic, dust was not a problem and he could see well. When he came to the hill where all of the riders had been stopped, there was nobody there except a couple of guys at the bottom with their bikes. Many of the riders had figured out that there was probably a checkpoint, and therefore water, on the other side of the hill and had left their bikes and walked over there.

The last quarter of the race he slowed down. Occasionally he picked off a slower rider. Nobody caught him. He was pooped. But his spirits were high. His first race and it looked like he was going to make the full 100 miles.

He expected to see a large group of spectators when he pulled across the finish, like there had been when he came through after the first loop. But when he came in he found that most of the spectators had drifted off. So what, he thought, elated that he had completed it.

When he rode up to the truck, Jack was drinking a beer and talking to another rider. Jack grinned at him.

“How’d you do, partner?”

“Pretty damn good,” Paul grinned back. “I finished.”

“Did you like it?”

“You better believe it. I loved it. But I’m sore as hell now.” He began peeling off his helmet, gloves, goggles and jacket. “How long have you been in?”

“Oh, about 20 minutes,” Jack said.

“You’re kidding.”

“No, really. Ask him,” he said, referring to the other rider.

“That’s right,” the rider said.

“And I thought I was really going.”

“Listen, you did great. It was your first race and you finished it. It was a fairly long one, too.”

“Would you say that was a hard course or about average?” Paul asked.

“Naw, that was an easy one,” Jack answered.

They stopped at a service station on the way home, attempting to get the outer layer of dirt off. When Paul looked in the mirror he saw that his whole head was a grey-brown from the dust. It was thick in his hair, caked in a layer on his lips, in his ears, down his back, everywhere. His eyes were blood red. When he tried to peel the dirt off his lips some of the skin went with it. He was bone tired now. And all of his muscles ached. They got hamburgers from a taco stand about halfway home. Paul was famished. But he was so exhausted he hardly felt like eating.

Then they got stuck in a traffic jam coming back into Los Angeles. It was almost dark when they finally got home. As they were unloading his bike, Mary and the kids came out to greet them.

“You look terrible,” Mary said. The kids were dancing about excitedly and asking him if he won.

“I know,” he told her. “And I feel just like I look. But I had a ball. I finished. And I passed a hell of a lot of riders.” To the kids he said, “No, daddy didn’t win. Maybe next time, okay?”

Jack climbed wearily back into his truck. “He did damn well for his first race,” he said proudly of his pupil.

Paul took a long hot shower and scrubbed vigorously to get clean. Then he soaked in very hot water and epsom salts. After that he crawled in bed with the Sunday paper. His eyes were so irritated he could hardly read. He fell asleep before he finished the funnies.

When the alarm went off in the morning he realized as soon as he got up to shut it off that he was as stiff as a board. For the next few days it was painful to climb the single flight of stairs to his office. His lips were badly chapped, cracked, and bled a couple of times when he opened his mouth wide. It was a couple of days before his eyes were back to normal. Everyone at work asked him what he had done to look that way. They all seemed impressed when he told them he had raced a hundred miles across the desert on a motorcycle. He reveled in his new glory. He knew he had the fever. He was addicted.

He and Jack went racing ’most every week after that. And he seemed to get just a shade better each time. About a month after his first race he received a finisher’s pin and the results from the club. He examined the pin carefully, then put it on a hat he had purchased just for that purpose. He grinned. Then he hunted down the list for his name. Out of 500 novices he had finished 125th. There had been 188 finishers. That meant that he had beaten 63 of the riders that finished. Counting all of the starters, he had done better than 375 of them. And some of them were riding bigger bikes than he had been riding. He had been the 85th 250cc finisher out of 102 250cc finishers. Not a bad beginning, he told himself. Not a bad beginning at all.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue