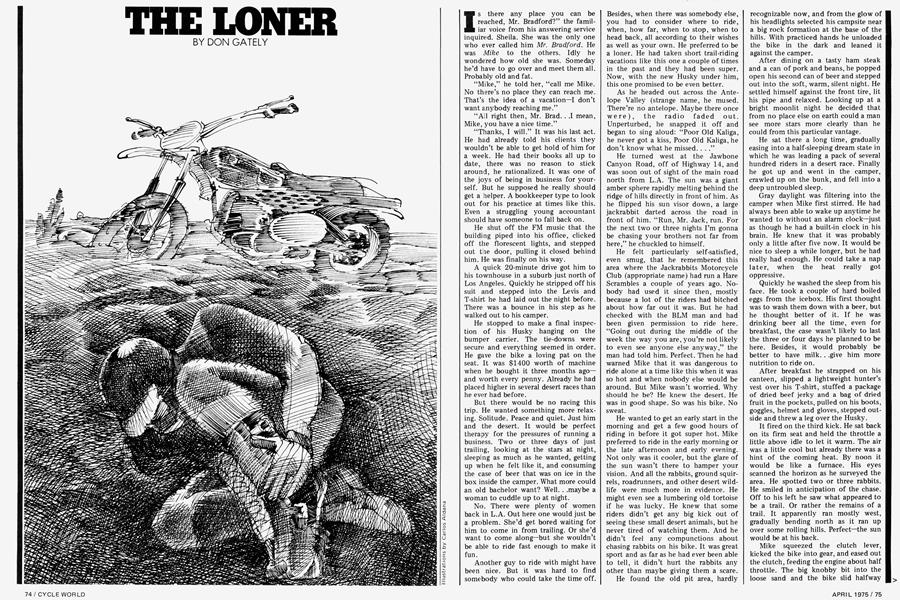

THE LONER

DON GATELY

Is there any place you can be reached, Mr. Bradford?" the familiar voice from his answering service inquired. Sheila. She was the only one who ever called him Mr. Bradford. He was Mike to the others. Idly he wondered how old she was. Someday he'd have to go over and meet them all. Probably old and fat.

“Mike,” he told her, “call me Mike. No there’s no place they can reach me. That’s the idea of a vacation—I don’t want anybody reaching me.”

“All right then, Mr. Brad. . .1 mean, Mike, you have a nice time.”

“Thanks, I will.” It was his last act. He had already told his clients they wouldn’t be able to get hold of him for a week. He had their books all up to date, there was no reason to stick around, he rationalized. It was one of the joys of being in business for yourself. But he supposed he really should get a helper. A bookkeeper type to look out for his practice at times like this. Even a struggling young accountant should have someone to fall back on.

He shut off the FM music that the building piped into his office, clicked off the florescent lights, and stepped out the door, pulling it closed behind him. He was finally on his way.

A quick 20-minute drive got him to his townhouse in a suburb just north of Los Angeles. Quickly he stripped off his suit and stepped into the Levis and T-shirt he had laid out the night before. There was a bounce in his step as he walked out to his camper.

He stopped to make a final inspection of his Husky hanging on the bumper carrier. The tie-downs were secure and everything seemed in order. He gave the bike a loving pat on the seat. It was $1400 worth of machine when he bought it three months ago— and worth every penny. Already he had placed higher in several desert races than he ever had before.

But there would be no racing this trip. He wanted something more relaxing. Solitude. Peace and quiet. Just him and the desert. It would be perfect therapy for the pressures of running a business. Two or three days of just trailing, looking at the stars at night, sleeping as much as he wanted, getting up when he felt like it, and consuming the case of beer that was on ice in the box inside the camper. What more could an old bachelor want? Well. . .maybe a woman to cuddle up to at night.

No. There were plenty of women back in L.A. Out here one would just be a problem. She’d get bored waiting for him to come in from trailing. Or she’d want to come along—but she wouldn’t be able to ride fast enough to make it fun.

Another guy to ride with might have been nice. But it was hard to find somebody who could take the time off. Besides, when there was somebody else, you had to consider where to ride, when, how far, when to stop, when to head back, all according to their wishes as well as your own. He preferred to be a loner. He had taken short trail-riding vacations like this one a couple of times in the past and they had been super. Now, with the new Husky under him, this one promised to be even better.

As he headed out across the Antelope Valley (strange name, he mused. There’re no antelope. Maybe there once were), the radio faded out. Unperturbed, he snapped it off and began to sing aloud: “Poor Old Kaliga, he never got a kiss, Poor Old Kaliga, he don’t know what he missed. . . .”

He turned west at the Jawbone Canyon Road, off of Highway 14, and was soon out of sight of the main road north from L.A. The sun was a giant amber sphere rapidly melting behind the ridge of hills directly in front of him. As he flipped his sun visor down, a large jackrabbit darted across the road in front of him. “Run, Mr. Jack, run. For the next two or three nights I’m gonna be chasing your brothers not far from here,” he chuckled to himself.

He felt particularly self-satisfied, even smug, that he remembered this area where the Jackrabbits Motorcycle Club (appropriate name) had run a Hare Scrambles a couple of years ago. Nobody had used it since then, mostly because a lot of the riders had bitched about how far out it was. But he had checked with the BLM man and had been given permission to ride here. “Going out during the middle of the week the way you are, you’re not likely to even see anyone else anyway,” the man had told him. Perfect. Then he had warned Mike that it was dangerous to ride alone at a time like this when it was so hot and when nobody else would be around. But Mike wasn’t worried. Why should he be? He knew the desert. He was in good shape. So was his bike. No sweat.

He wanted to get an early start in the morning and get a few good hours of riding in before it got super hot. Mike preferred to ride in the early morning or the late afternoon and early evening. Not only was it cooler, but the glare of the sun wasn’t there to hamper your vision. And all the rabbits, ground squirrels, roadrunners, and other desert wildlife were much more in evidence. He might even see a lumbering old tortoise if he was lucky. He knew that some riders didn’t get any big kick out of seeing these small desert animals, but he never tired of watching them. And he didn’t feel any compunctions about chasing rabbits on his bike. It was great sport and as far as he had ever been able to tell, it didn’t hurt the rabbits any other than maybe giving them a scare.

He found the old pit area, hardly recognizable now, and from the glow of his headlights selected his campsite near a big rock formation at the base of the hills. With practiced hands he unloaded the bike in the dark and leaned it against the camper.

After dining on a tasty ham steak and a can of pork and beans, he popped open his second can of beer and stepped out into the soft, warm, silent night. He settled himself against the front tire, lit his pipe and relaxed. Looking up at a bright moonlit night he decided that from no place else on earth could a man see more stars more clearly than he could from this particular vantage.

He sat there a long time, gradually easing into a half-sleeping dream state in which he was leading a pack of several hundred riders in a desert race. Finally he got up and went in the camper, crawled up on the bunk, and fell into a deep untroubled sleep.

Gray daylight was filtering into the camper when Mike first stirred. He had always been able to wake up anytime he wanted to without an alarm clock—just as though he had a built-in clock in his brain. He knew that it was probably only a little after five now. It would be nice to sleep a while longer, but he had really had enough. He could take a nap later, when the heat really got oppressive.

Quickly he washed the sleep from his face. He took a couple of hard boiled eggs from the icebox. His first thought was to wash them down with a beer, but he thought better of it. If he was drinking beer all the time, even for breakfast, the case wasn’t likely to last the three or four days he planned to be here. Besides, it would probably be better to have milk. . .give him more nutrition to ride on.

After breakfast he strapped on his canteen, slipped a lightweight hunter’s vest over his T-shirt, stuffed a package of dried beef jerky and a bag of dried fruit in the pockets, pulled on his boots, goggles, helmet and gloves, stepped outside and threw a leg over the Husky.

It fired on the third kick. He sat back on its firm seat and held the throttle a little above idle to let it warm. The air was a little cool but already there was a hint of the coming heat. By noon it would be like a furnace. His eyes scanned the horizon as he surveyed the area. He spotted two or three rabbits. He smiled in anticipation of the chase. Off to his left he saw what appeared to be a trail. Or rather the remains of a trail. It apparently ran mostly west, gradually bending north as it ran up over some rolling hills. Perfect—the sun would be at his back.

Mike squeezed the clutch lever, kicked the bike into gear, and eased out the clutch, feeding the engine about half throttle. The big knobby bit into the loose sand and the bike slid halfway around before biting in and shooting forward.

The strong, rhythmical pap-pap-pap of the big two-stroke Single was almost a sensual pleasure to him. It was a reassuring signal from the bike that all was well. A sign of strength and reliability. A sense of well-being came upon him as he charged out across the desert floor, alternating between standing on the pegs for jumps, ripples, washboard and whoop-dee-doos, and resting on the seat for crashing through bushes, plowing through sandwashes, or just cruising on the solid even areas. The air cooled his arms enough to bring goosebumps, but it was very invigorating. Mike felt better than he had for a long time.

Occasionally a jack would cross the trail in front of him, or pop out from under a brush and head in the direction he was going. Then Mike would stand on the pegs and roll the throttle on harder. It was like he was in a race again, except the competition was the rabbit instead of another bike. The rabbits could dodge and swerve to miss rocks or bushes or other obstacles. They could make a 90-degree turn almost without slowing down. . .and they could run 60 miles an hour! But for some reason, the rabbits seldom turned. They would run straight down the trail in front of the bike, veering only enough to go around bushes. So Mike could chase rabbits as they appeared without having to make any significant change of direction. He knew that if he started running around in circles he could get lost. Subconsciously he was taking a mental inventory of the landmarks. He was desert-wise and experienced, but it never paid to get too cocksure.

He stopped about eight o’clock. Most of the rabbits had disappeared now, to rest during the heat of the day. Mike found a large rock formation that provided ample shade from the rising sun. He settled down in the warm, soft sand and leaned against the rock. He took off his gloves, goggles and helmet, and took the beef jerky from his pocket. He gnawed off an inch-long section and began chewing. The salty, stringy meat tasted great out there on the desert. Once he had tried to eat a piece of jerky at home, but he hadn’t cared much for it. Somehow it wasn’t the same. To really enjoy beef jerky, you had to be out on the desert. It was already hot. Mike judged it to be at least 90 degrees.

He figured he must have come 50 miles. The extra-large plastic tank that he had bought—just for rides like thisheld about 4.2 gallons. Running the way he had been, he ought to be getting about 35 miles to a gallon. That would give him a range of 140 miles. He looked over at the bike, standing almost straight up, propped against the rock formation. He could see the level of gasoline through the tank, and it appeared that he still had more than a half tank. He decided to ride on for another half hour or so, then turn around and head back. Allowing for another rest stop on the way back, that ought to put him back at his truck about 11:30 or thereabouts. Just right. He’d find some shade and then kick off his boots and just lie back and drink beer. Maybe sleep some. Then get up and ride some more in the late afternoon.

He took several mouthfuls of water from the canteen, rolled them around in his mouth before swallowing so as to rinse the salt taste of the beef jerky away, then took a good long drink to quench his thirst, and put the canteen back in its holster hanging from the olive web belt at his waist. He wiped the dust off of his goggles onto his T-shirt, stretched the sweat-dampened elastic band around his head, pulled the helmet on and cinched the strap snugly under his chin, slipped on the gloves, and remounted. The still-warm engine responded eagerly to his first crank.

He had gone less than a mile when he was surprised by another jack that ran out on the trail in front of him. He hadn’t expected to see any this late in the day, but what was more surprising was seeing a jack in this area. There was no brush here. No bushes, no greasewood, or joshua—nothing but a little spare grass growing out of the sand amongst the rocks. Usually you only found rabbits where there was brush. Anyway, he welcomed the unexpected diversion. The jack ran along the trail in a fairly straight direction for perhaps 50 yards, then angled quickly off to his right at about 45 degrees. Mike hit his rear brake and threw the Husky into a slide in the direction the rabbit had taken. It was really bitchin’!

The rabbit dropped into a sandwash, scooted across and up the other bank, and turned sharply to the left around a large rock formation. He had gotten out of Mike’s sight, but Mike figured he’d spot him again. He dropped into the wash, roared up the other side and lofted the front end high in the air in a spectacular wheelie. The thought flashed instantly through his mind that he wished one of those photographers who are always at some spot like this on desert races had been on hand to snap it, or at least that there had been a small group of spectators on hand to admire it. He set the bike down and heeled it over hard to swing around the rock formation. Too late he saw that what had appeared to be a clear trail around the formation was obstructed with a huge boulder—and more big rocks to the right. There was no way around it, no time to stop, really not even any time to think or to react. “Oh hell!” was all Mike had time to think before he plowed headlong into it. The front wheel stopped dead, but the momentum of the bike pitched Mike forward over the handlebars and sent him flying some 15 feet before he landed in a spot where many brick-size rocks were scattered across the sand. The bike flipped over and landed upside down on top of the boulder.

The air was gone from him and he seemed to suddenly ache all over. He saw stars, his vision blurred. And he thought he was going to throw up. But he did not lose consciousness. His first thought was of the bike: “What a way to tear up such an expensive toy! I probably did at least a few hundred dollars worth of damage. She’ll never be the same.”

After a couple of moments he caught his breath. . .and began to realize how much he hurt. Slowly he raised himself from the spread-eagle position in which he had landed, turned over and sat up. He began to take stock of his injuries. His arms were badly gashed and bruised from the rocks, but did not seem to be broken. Thank God for that! The hunter’s vest and T-shirt had protected his torso so that it was not scraped as badly as his forearms, but he could feel the scrapes, gashes and bruises, and saw the two layers of material had torn through in several spots. He could guess from the way his body was burning that he had a few pretty raw spots. His back, shoulders, neck, head, rear, all seemed to have escaped unscathed, probably because he landed face down. His thighs were bruised and probably scratched, but not too badly. His knees both were preety badly gouged and were bleeding. But he still didn’t seem to have anything broken.

He looked over at the bike and saw the gas running slowly out from under the cap and dripping on the rock directly beneath it. I better get up and right it before all the gas runs out, he thought. Gingerly he started to get to his feet. . .but a sharp pain came from his right ankle and he found that he could not put his weight on it. Oh oh, he was alarmed now, this could be bad. It feels like it may be broken. Or at least badly sprained. He sat down and put his hands around the ankle. Through the boot he could feel it swelling and throbbing. “Damn'it!” he said aloud. He knew that it would be a mistake to unbuckle the boot, so he couldn’t even look at it. . .not that he would know much just from seeing it anyway.

Well, he told himself, whatever else I do, I’ve got to get that bike turned over. If I lose all the gas out here I am really screwed. Slowly, painfully, he crawled across the rocky trail to the bike. It took several minutes of the hardest kind of struggling to get the bike back on its wheels and to prop it up with a rock under the frame. When he finished he was terribly thirsty. He reached for his canteen and to his horror found that it was gone. He experienced an instant of panic. If he was out here in this kind of heat without water he could die. Then he saw it lying in the rocks where he had landed. Half crawling, half walking with a limp, he made his way to the canteen. The water was warm and stale, but he wanted to drink it all. He didn’t. He had enough presence of mind to know that he would have to carefully ration the water until he got out of this mess. He wished to hell there were some shade. Even a breeze, any kind of respite from the heat. But the sun bore down on him unmercifully. It has to be a hundred and ten now, he thought bitterly.

Mike sat down and settled himself as comfortably as possible in the rocks and fished si prune from the bag of dried fruit. Dropping it in his mouth, he began to suck it slowly and consider his predicament. The thing now would be getting out of here. Never mind trying to get back to the camper. Just figure out where the closest road would be. Get to civilization and get food and water. Then have a doctor look him over. Especially the ankle. Then he could al ways worry about finding somebody to take him back to his truck.

What if the bike wouldn’t start? For the second time he felt a surge of panic. Take it easy, he told himself. Everything will work out if you don’t lose your head. If you start letting yourself get psyched out you’re in deep trouble. But he knew that two-strokes were temperamental. If the bike had been upside down too long, it could have loaded up. And he knew it would be hard to crank it left-footed when he couldn’t even stand to put any weight on the right foot. Better get back over to the scooter and see what shape she’s in, he decided.

Again he performed his grotesque crab-like walk, dragging the broken ankle, to the bike. He sat down next to it and began to look it over. At first it appeared okay. But then he saw that the down tube was very badly cracked at the crown. It looked as though it would surely buckle the first time he hit even the slightest bump. And there was no way to go even a mile in this terrain without hitting a hell of a lot of really rough bumps. It probably would serve no useful purpose to try to get the bike started, since he was sure he couldn’t ride it any distance anyway.

But he couldn’t walk out. Or could he? He sure as hell couldn’t stay here. He had only three choices: stay with the bike, try to get it started and ride out, or walk out. He decided the best thing to do would be to sit tight and really think it out. This was no time to make the wrong decision. Think it out; weigh the alternatives, the advantages and disadvantages of each, then stay cool—that was an ironic choice of words in this heat—and be smart.

Okay, so alternative number one: ride it out. The big IF was if he could get it started. And secondly, would it make it? He doubted it. He now saw that the front rim was badly bent and that the tire had gone flat. That, along with the frame almost broken in two, made his chances of going anywhere on it very slim indeed.

Alternative number two: walk out. That seemed foolish, too. Even if he had no injuries, he had no idea which way to go or how far it would be till he hit a road. He figured he had ridden somewhere between 50 and 60 miles. If it had all been in a straight direction, he should be getting to a town or at least a paved road. But the desert didn’t run in straight lines. You followed the terrain. And even though you tried to pay attention to the direction you were headed, it was the easiest thing in the world to just go around in a big circle. . .particularly in the middle of the day when the sun was directly overhead. You turned so gradually that you were not aware of it.

He tried to think about a map of the area, and about the country as he knew it. What towns might he be near? He had been coming west and north, he thought, from Highway 14. So Ridgecrest and Inyokern would be a long ways east. Bakersfield? No, still too far west. Tehachapi? Possible. But likely a good ways south and a little west. Lake Isabella. Yes. That was a possibility. But how far? He would have had to cross mountains to get there, but not real high ones. Had this country he had been riding over been some of those mountains? It seemed like the best bet, but he had no idea how far it would be. Maybe just a few miles north of here. The thought encouraged him. But walking, hobbling really, would be a pure bitch. Especially in this heat.

Maybe, if he were going to try to walk out, he should wait until night. It would be much cooler. That would preserve his strength. And his water. His precious water. Also, if he waited till the sun started to set he could be more certain of his directions. But if it were dark wouldn’t he stumble into rocks and things? No, he remembered, last night had been a full moon. He’d be able to see good enough.

It seemed preferable to the third alternative. Really, it would be pointless to stay here. Judging by the trail, nobody had been this way for a long time. It wasn’t likely that anybody would be by this way again soon enough to do him any good. Then an idea hit him: what if an airplane passed over? There was a small private airport somewhere around Lake Isabella. If he was close, one of them might pass over. Maybe they’d see the bike. Maybe the red gas tank would attract them. Or he could build a fire. But there wasn’t a damn thing to build one out of. Rocks and sand don’t burn. And he didn’t have any matches, either, damn it!

He .decided he would try to start the bike as soon as the sun was low enough for him to determine which way north was. If he couldn’t get it to run, he’d start walking. He knew that the next few hours would be bad. The sun would be directly overhead so that he wouldn’t be able to find even a little shade from a rock. Nothing to do but lay on the ground and cook.

He moved around until he found a stretch of sand without too many rocks on it. He cleared the rocks away, then began digging into the sand with his hands. He reasoned that if he could dig down six or eight inches the earth would be cooler. It took him about an hour to digout a shallow entrenchment, but sure enough it was cooler. He was pleased at his wisdom. Probably digging my own grave, he mused, trying to see the irony in it. But it wasn’t funny.

(Continued on page 94)

Continued from page 77

Lying in the dirt, he thought about his cuts. They would have dirt in them. That would mean infection. Should he use any of his water to wash them out? No. There was only about half a canteen left. He’d rather risk infection than die of thirst. But before he started walking out he would pour a few drops on his handkerchief and rub them off. It would hurt, but it might help a little in preventing the infection.

He tried not to think about how thirsty he was. Or how hot. He put a piece of dried fruit in his mouth every now and then, and concentrated on how long he could make it last. He found that by just letting it dissolve and then gradually chewing it, he could make a prune last a long time. He had no wristwatch, but he judged that a good sized prune lasted about an hour. He counted the number of pieces of dried fruit and the number of sticks of jerky that he had. He decided that by carefully rationing them he should have enough to last three or four days. He didn’t plan to be out on this desert that long, but you couldn’t tell. He couldn’t afford to just eat them. And he would try to allow himself only one mouthful of water every couple of hours.

He started thinking about all the things he had done wrong. He had broken an awful lot of basic rules. The things you read in all the motorcycle safety handbooks. Rule One: Never ride alone. Rule Two: Always let someone know where you are going and when you are expected to return. Rule Three: Always carry matches. Rule Four: Don’t blast into a blind turn when you don’t know what’s there. Rule Five: Never chase jackrabbits. Rule Six: Always wear protective leathers when riding in the rough. Everybody broke some of the rules some of the time. But he had really done it up brown.

He fell into a kind of stupor. He was almost strangling when he awoke with a terrible start—a prune seed stuck in his craw. He gagged it up, spit it out. Settling his head back in the sand, he said to himself, “Rule Seven: Never fall asleep with a prune in your mouth.” He stayed in a fitful half-sleep stage for a couple of hours. Then he sat up and looked around. The sun was starting to drop a little. Probably about four o’clock. He decided he could allow himself a mouthful of water. If he got delirious from lack of water he’d never get out. He had to keep his wits about him. He held the tepid water in his mouth a long time. He was really worried now. The gravity of his situation was really settling in on him. He was more than depressed. . .he was scared. But he vowed not to panic no matter what.

(Continued on page 96)

Continued from page 94

When the sun started getting low in the afternoon sky, he worked his way back to his bike. He primed the carburetor, then tried to crank it by hand. He could push it through, but not fast enough to start it. After he tried three or four times he decided he would have to use his left leg. He tried to balance his weight on his right foot as carefully as possible, putting as much of his weight as he could on the handlebars. Then he pushed his left leg down without taking the right one off the ground. But he couldn’t get enough force and the starter snapped back, painfully whipping his left foot. Damn it, now he didn’t even have one completely good foot. But he tried again, this time jumping off the ground in the usual way. The bike still didn’t show any signs of firing. And when he came back down on his right foot the pain in his ankle was excruciating. Tears in his eyes, he sat down in severe pain. He was sure now that the bike would not start. He would have to walk out.

He waited another half hour, but the pain eased off only a little. No use procrastinating any longer. He knew which way north was, he might as well start.

It was hard, slow going. Every step was new pain. He constantly wanted to stop. His throat was burning dry. His muscles ached. The cuts and bruises throbbed. But he pushed on. It took two hours to make the first mile. Then it was uphill. And a pretty steep one at that, with more hills and ridges to come. He didn’t feel that he had any choice. He pressed on, resting frequently. Sometimes he sat, but usually he just rested by standing still. It was too hard to get back up once he sat. He wished he had a cane.

It was about 11 o’clock when Mike reached the top of the ridge. No more mountains lay before him. Far off to his right he could see the lights of a town. Probably Ridgecrest. But it looked to be a good 25 miles away. Just a dim glimmering on the horizon. He decided it was too far. Slowly he scanned the horizon, making a full 360-degree turn. He saw no other lights. Nothing. Perhaps there was a road passing someplace closer. If he could just catch sight of passing headlights he could head in that direction. He didn’t even give a damn if he never found his bike again. Getting out was all that mattered. He sat there for three hours, slowly turning in circles and searching for lights. But all he saw were those same lights of that distant town, beckoning, torturing, luring, tormenting him. He thought about the people there. Some were eating, some were drinking, some were making love. Most were probably sleeping comfortably now. Maybe in a few days they’d read the story of the motorcycle rider found dead on the desert. Stop thinking like that, he told himself. But the thought refused to disappear. He couldn’t decide whether he ought to strike out for the town or not. But he could only make a few miles each night. And during the day there would be too much chance of losing direction and going in circles. He might just wander around until he died.

(Continued on page 98)

Continued from page 96

If somebody happened across his bike they would have no way of knowing which way he had gone. He shivered now. The desert gets chilly at night. He wished he had a jacket. If he tried to go back to his bike in the dark he might miss it. He’d wait for daylight and go back.

It was about 10 in the morning when he got back to the bike. Already it was super hot again. He ate an apricot, then a prune. Very slowly. He held his mouthful of water on his swollen tongue for a long time before letting it pass over his parched throat.

Maybe they’re out looking for me now, he thought. Maybe somebody came across the truck and figured out that if nobody had come back to it for a long time that maybe somebody was lost out here or something. He laid down in the rocks and went to sleep.

About one o’clock he was awakened by the sound of motorcycles. They were far off but it sounded like they were coming this way. Painfully he climbed on top of the rock formation for a better vantage. He began shouting, which was painful as hell to his dry throat. His voice sounded strange, hollow, futile, meaningless to him. He listened again but the bikes were getting farther away. He shouted over and over, turning in every direction in the hope that his voice would reach the riders. But the bike sounds disappeared. He listened for them for a long time. Then he thought, if they’re out here riding they may do like I was going to do, go back the way they came. That would mean they’d be passing again. He thought about which direction the sounds had come from. South. He was pretty sure they had been south of him. He started hobbling in that direction.

After a couple of hours, when he had made about a mile and a half, he heard them coming again. They were closer this time. Two-strokes. Sounded like two of them. He began shouting as loud as he could, standing as tall as possible and waving his arms over his head. Then he saw them, two Yamahas, perhaps three quarters of a mile away and heading east. He shouted harder, moved as fast as he could, disdainful of the pain from his ankle. He continued waving his arms over his head. He felt relief surging through him.

(Continued on page 100)

Continued from page 98

But his relief quickly turned to even greater despair when it became obvious they were not going to see him. He kept shouting as loud as his cracking throat would let him, meanwhile stooping and picking up rocks to throw in their direction. But they never looked his way. Tears welled up in his eyes and he came to a moment of real panic.

When he got himself under control again he decided to stay there in case the riders came by again. Or maybe some others would pass by. Maybe there were a bunch of bikers out looking for him. But hours passed and he saw no more signs of life. Finally, when it was nearly dark, he dejectedly began the slow painful limp back to his bike.

When he was nearly there, a plane passed overhead. A small private plane. Flying fairly low and fairly slow. He again felt heartened. It had to be more than just a coincidence. He hadn’t seen a plane all the time he’d been out here until now. Surely the fact that the bikers had gone by and now the plane meant that there was a search party out looking for him. Somebody must have come upon his camper after all.

By the time Mike reached his bike he knew what he had to do. He had to build a fire. That was the one way they could spot him. Otherwise it was like looking for a needle in a haystack; they could fly over very close, or ride by very near, and still not see him. But the smoke of a fire could be seen a long way on the desert. He cursed his stupidity for not having brought matches along.

Mike reasoned that they would stop looking after dark and wait until daylight to start again. He had to have a fire ready to go by then. But how? He had no matches. There was no wood here to burn. He didn’t even have anything glass that he could use to catch the sun’s rays. But there must be a way. The motorcycle still had gasoline in it. If only there were a way to ignite it. Wait a minute, he thought. . .ignite, maybe that’s it. Ignite. . .spark. The bike has to have a spark to run. He limped over to the bike, took the spark plug wrench off the frame where it was secured with strong clamps, and removed the plug from the engine head. Then he hooked the ignition wire back to the tip of the plug and held the other end against the engine fins. . .the way you tested to see if a plug was firing.

(Continued on page 102)

Continued from page 100

It was a very awkward position. He had to hold the plug steady against the fins with one hand while he pushed the kickstarter through with the other. But he managed to do it. And in the fading light he saw what he wanted; she was getting spark!

He felt as though a great weight had been taken from his shoulders. He was sure that with gasoline and a spark he would be able to get a fire going. He thought about it until he fell asleep.

He woke gradually. The sun was already high. Why hadn’t he awakened at dawn? Then he realized he had a fever. He felt very, very weak. He wasn’t hungry any longer. It took a great effort for him to sit up. God, what if he had slept and they had passed by this way? Would they come again? But the day wore on and there was no sign of any search party. Mike began to feel more desperate than ever. Now he was too weak to walk out. And his water was almost gone. . .only about a mouthful or two remained in the canteen.

His only hope now was the fire—and that he had enough strength to turn the engine over fast enough to get spark. But he still didn’t know what there was to bum. Let’s see, he thought: The liquid gasoline itself doesn’t burn. It burns in a gas form. It’s like atomized in the combustion chamber and it explodes. I think that’s the theory. Anyway, they say you can throw a lit match on gasoline and it won’t always burn. You need fumes.

Then another idea hit him. Why not take his vest and stuff it in the gas tank and get it good and wet? Then lay it on the engine next to the plug. As it dried out there would be fumes. Of course he’d have to keep dipping it every so often. And he wouldn’t know for sure if it would work until the crucial time when a plane flew over. But it was a chance. . .his only chance really. He felt very weak, and the fever seemed to be getting worse. He fought dizziness. He fought the desire to sleep. He had to be ready.

The day passed without a sign of anyone. Mike realized they had not been out looking for him after all. If they had been, they still would be. They wouldn’t have quit that easily. And the desert wasn’t so big that some of them wouldn’t have at least passed within his hearing range. It must have just been a coincidence after all. But there was still a chance that some plane might just happen to pass by. He’d wait. And pray. That’s all that was left.

For the first time he thought seriously about what it would be like to die. What would happen to his business? To his family back East? They’d get over it after a time. He wondered if there really was a heaven and a hell and a God and all that. He had never really thought there was. Maybe he’d have a chance to find out pretty soon.

The sun was nearly setting when he heard the sound of a small plane. Somehow he managed to scramble to his feet. Scanning the sky, he saw it coming from the east. It looked like it might pass pretty near. This was it. . .now or never! He pushed the kickstarter through while he held the plug connected to the ignition wire against the cylinder head that had the gasolinedampened vest stretched against it. It worked! To his immense satisfaction, it worked! The vest started slowly, but the flame spread quickly. Mike stepped back from the bike and a moment later the gas tank ignited with a low “poof”. . .and seconds later he had a roaring flame going.

He looked up and saw the plane circling back. He ripped his T-shirt off and began waving it wildly over his head. They saw him. The twin-engine Cessna dropped down to about 50 feet and flew in wide circles around him. He could see two men in the plane. They gestured that they understood his situation.

It was only about 20 minutes before the Sheriff’s Department helicopter appeared. Through a loud speaker they asked if he was injured. He shook his head in the affirmative and pointed to his ankle. Soon a litter basket appeared and was lowered out of the belly of the chopper as it hovered about 20 feet off the ground. When it was down, two men came down a rope ladder.

“You alone?” one of them asked.

Mike nodded, indicating that he was.

“It’s pretty dangerous to ride by yourself in country like this,” the other man said as they prepared the litter basket for him.

“I know,” Mike managed to croak.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue