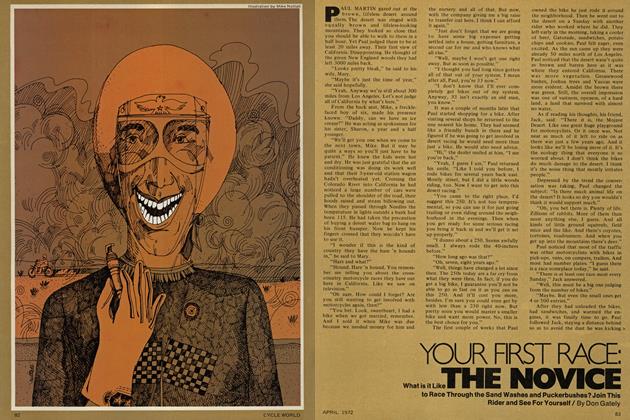

DESERTIZING THE YAMAHA TWIN JET 100

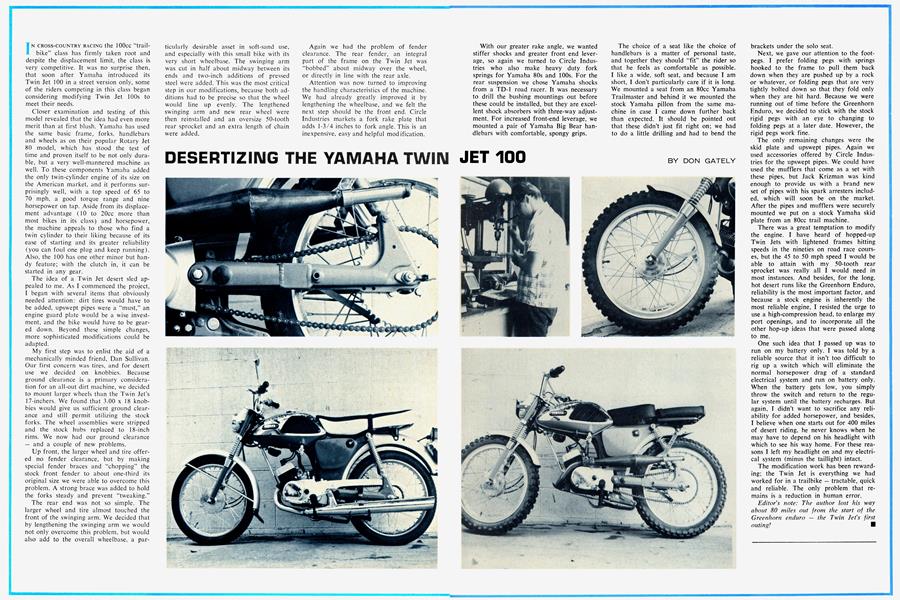

IN CROSS-COUNTRY RACING the 100cc “trail-bike” class has firmly taken root and despite the displacement limit, the class is very competitive. It was no surprise then, that soon after Yamaha introduced its Twin Jet 100 in a street version only, some of the riders competing in this class began considering modifying Twin Jet 100s to meet their needs.

Closer examination and testing of this model revealed that the idea had even more merit than at first blush. Yamaha has used the same basic frame, forks, handlebars and wheels as on their popular Rotary Jet 80 model, which has stood the test of time and proven itself to be not only durable, but a very well-mannered machine as well. To these components Yamaha added the only twin-cylinder engine of its size on the American market, and it performs surprisingly well, with a top speed of 65 to 70 mph, a good torque range and nine horsepower on tap. Aside from its displacement advantage (10 to 20cc more than most bikes in its class) and horsepower, the machine appeals to those who find a twin cylinder to their liking because of its ease of starting and its greater reliability (you can foul one plug and keep running). Also, the 100 has one other minor but handy feature; with the clutch in, it can be started in any gear.

The idea of a Twin Jet desert sled appealed to me. As I commenced the project, I began with several items that obviously needed attention: dirt tires would have to be added, upswept pipes were a “must,” an engine guard plate would be a wise investment, and the bike would have to be geared down. Beyond these simple changes, more sophisticated modifications could be adapted,

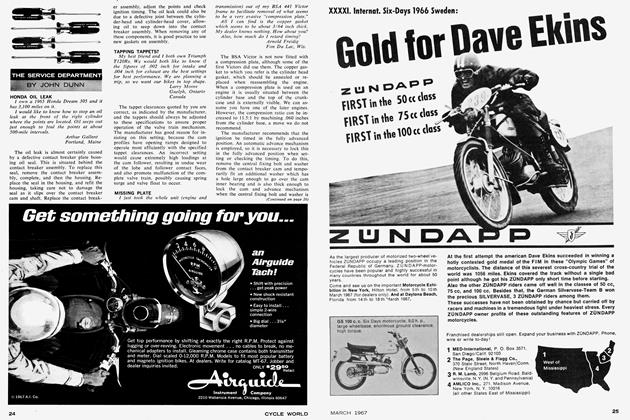

My first step was to enlist the aid of a mechanically minded friend, Dan Sullivan. Our first concern was tires, and for desert use we decided on knobbies. Because ground clearance is a primary consideration for an all-out dirt machine, we decided to mount larger wheels than the Twin Jet’s 17-inchers. We found that 3.00 x 18 knobbies would give us sufficient ground clearance and still permit utilizing the stock forks. The wheel assemblies were stripped and the stock hubs replaced to 18-inch rims. We now had our ground clearance — and a couple of new problems.

Up front, the larger wheel and tire offered no fender clearance, but by making special fender braces and “chopping” the stock front fender to about one-third its original size we were able to overcome this problem. A strong brace was added to hold the forks steady and prevent “tweaking.” The rear end was not so simple. The larger wheel and tire almost touched the front of the swinging arm. We decided that by lengthening the swinging arm we would not only overcome this problem, but would also add to the overall wheelbase, a particularly desirable asset in soft-sand use, and especially with this small bike with its very short wheelbase. The swinging arm was cut in half about midway between its ends and two-inch additions of pressed steel were added. This was the most critical step in our modifications, because both additions had to be precise so that the wheel would line up evenly. The lengthened swinging arm and new rear wheel were then reinstalled and an oversize 50-tooth rear sprocket and an extra length of chain were added.

Again we had the problem of fender clearance. The rear fender, an integral part of the frame on the Twin Jet was “bobbed” about midway over the wheel, or directly in line with the rear axle.

Attention was now turned to improving the handling characteristics of the machine. We had already greatly improved it by lengthening the wheelbase, and we felt the next step should be the front end. Circle Industries markets a fork rake plate that adds 1-3/4 inches to fork angle. This is an inexpensive, easy and helpful modification.

DON GATELY

With our greater rake angle, we wanted stiffer shocks and greater front end leverage, so again we turned to Circle Industries who also make heavy duty fork springs for Yamaha 80s and 100s. For the rear suspension we chose Yamaha shocks from a TD-1 road racer. It was necessary to drill the bushing mountings out before these could be installed, but they are excellent shock absorbers with three-way adjustment. For increased front-end leverage, we mounted a pair of Yamaha Big Bear handlebars with comfortable, spongy grips.

The choice of a seat like the choice of handlebars is a matter of personal taste, and together they should “fit” the rider so that he feels as comfortable as possible. I like a wide, soft seat, and because I am short, I don’t particularly care if it is long. We mounted a seat from an 80cc Yamaha Trailmaster and behind it we mounted the stock Yamaha pillon from the same machine in case I came down further back than expected. It should be pointed out that these didn’t just fit right on; we had to do a little drilling and had to bend the brackets under the solo seat.

Next, we gave our attention to the footpegs. I prefer folding pegs with springs hooked to the frame to pull them back down when they are pushed up by a rock or whatever, or folding pegs that are very tightly bolted down so that they fold only when they are hit hard. Because we were running out of time before the Greenhorn Enduro, we decided to stick with the stock rigid pegs with an eye to changing to folding pegs at a later date. However, the rigid pegs work fine.

The only remaining changes were the skid plate and upswept pipes. Again we used accessories offered by Circle Industries for the upswept pipes. We could have used the mufflers that come as a set with these pipes, but Jack Krizman was kind enough to provide us with a brand new set of pipes with his spark arresters included, which will soon be on the market. After the pipes and mufflers were securely mounted we put on a stock Yamaha skid plate from an 80cc trail machine.

There was a great temptation to modify the engine. I have heard of hopped-up Twin Jets with lightened frames hitting speeds in the nineties on road race courses, but the 45 to 50 mph speed I would be able to attain with my 50-tooth rear sprocket was really all I would need in most instances. And besides, for the long, hot desert runs like the Greenhorn Enduro, reliability is the most important factor, and because a stock engine is inherently the most reliable engine, I resisted the urge to use a high-compression head, to enlarge my port openings, and to incorporate all the other hop-up ideas that were passed along to me.

One such idea that I passed up was to run on my battery only. I was told by a reliable source that it isn’t too difficult to rig up a switch which will eliminate the normal horsepower drag of a standard electrical system and run on battery only. When the battery gets low, you simply throw the switch and return to the regular system until the battery recharges. Bpt again, I didn’t want to sacrifice any reliability for added horsepower, and besides, I believe when one starts out for 400 miles of desert riding, he never knows when he may have to depend on his headlight with which to see his way home. For these reasons I left my headlight on and my electrical system (minus the taillight) intact.

The modification work has been rewarding; the Twin Jet is everything we had worked for in a trailbike — tractable, quick and reliable. The only problem that remains is a reduction in human error.

Editor’s note: The author lost his way about 80 miles out from the start of the Greenhorn enduro — the Twin Jet’s first outing! M