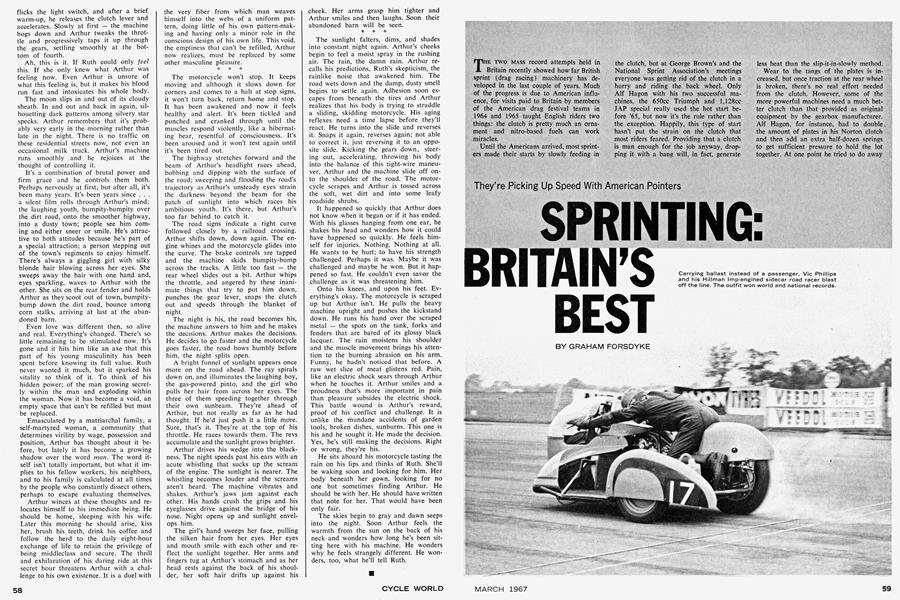

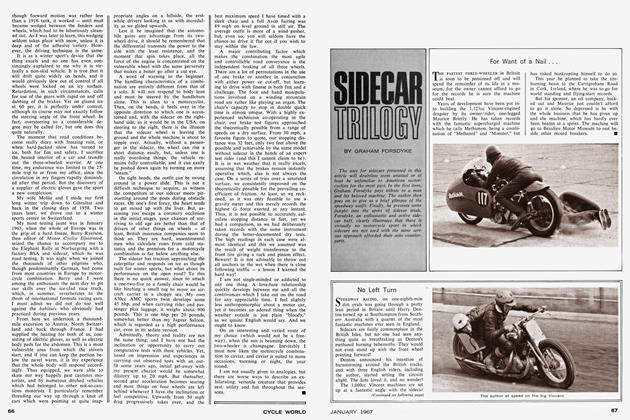

SPRINTING: BRITAIN’S BEST

They're Picking Up Speed With American Pointers

GRAHAM FORSDYKE

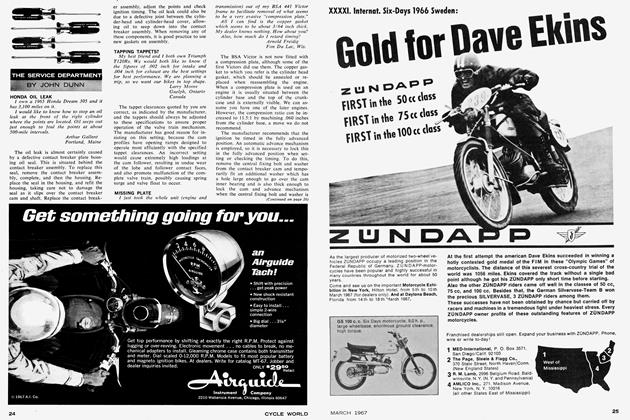

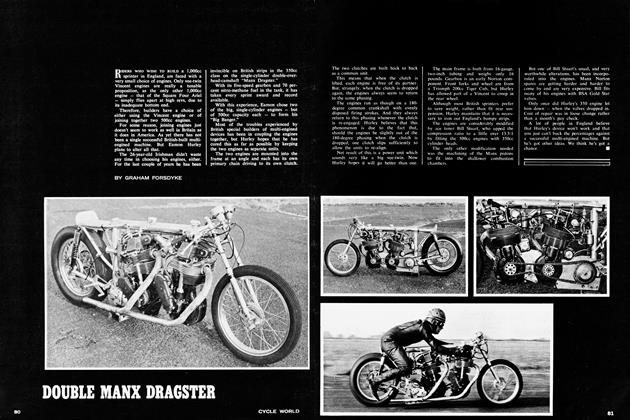

THE TWO MASS record attempts held in Britain recently showed how far British sprint (drag racing) machinery has developed in the last couple of years. Much of the progress is due to American influence, for visits paid to Britain by members of the American drag festival teams in 1964 and 1965 taught English riders two things: the clutch is pretty much an ornament and nitro-based fuels can work miracles.

Until the Americans arrived, most sprinters made their starts by slowly feeding in the clutch, but at George Brown’s and the National Sprint Association’s meetings everyone was getting rid of the clutch in a hurry and riding the back wheel. Only Alf Hagon with his two successful machines, the 650cc Triumph and l,128cc JAP special really used the hot start before ’65, but now it’s the rule rather than the exception. Happily, this type of start hasn’t put the strain on the clutch that most riders feared. Providing that a clutch is man enough for the job anyway, dropping it with a bang will, in fact, generate less heat than the slip-it-in-slowly method.

Wear to the tangs of the plates is increased, but once traction at the rear wheel is broken, there’s no real effort needed from the clutch. However, some of the more powerful machines need a much better clutch than that provided as original equipment by the gearbox manufacturer. Alf Hagon, for instance, had to double, the amount of plates in his Norton clutch and then add an extra half-dozen springs to get sufficient pressure to hold the lot together. At one point he tried to do away with the clutch altogether by using a stand which held the rear wheel off of the ground while the power was cranked up, and then dropped it at the flick of a handlebar lever. It was a good theorv, and worked quite well, but the imoroved clutch with which he turned up this year made it an unnecessary frill.

Even the smaller machines are using the clutch as little as possible. Des Heckle’s fantastic little 250cc Villiers Starmaker makes the most ungainly starts imaginable, but they are effective. He doesn’t use a slick tire, but soins off with a 3.50-section racing cover. Heckle is about the only top class runner still using gas. There are no special records for gas competitors, but Heckle finds enough steam without the need for special fuel.

Heckle’s single-cylinder two-stroke breathes through an Amal GP carburetor and has an exhaust system which is nearly all expansion chamber. His fast times are helped by fantastically quick gear changes through four-speed gearbox which has its shafts supported on needle roller bearings.

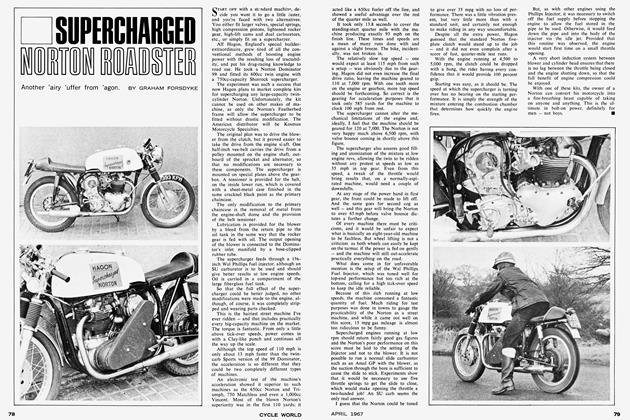

Despite tremendous cost in Britain, most of the record brigade are now running on fairly high percentages of it with their methanol-based fuels, but many of them are having great trouble in firing quantities over 20 percent. George Brown led the nitro experiments in Britain, but he is still limited to a small percentage because the Vincent engine just cannot cope with higher ratios.

Brown is now experimenting with transistor ignition and has run six-volt electrics on 12-volt batteries in an endeavor to improve the spark.

Hagon’s big JAP copes with 60 percent nitro when he’s really pressed, but it’s been an expensive business. The standard JAP pistons just wouldn’t take the load, and experiments were tried with Ford car and ESO speedway pistons. The ESO items worked the best, but even with them, the big engine couldn’t be guaranteed to do more than one or two hard runs without ventilating the piston crowns. Alf almost gave up, but, in the end, tried cast pistons designed for a G50 Matchless single-cylinder racer. The engine’s first run with the new pistons was at the records meeting and the pistons held up, giving Alf a couple of records. This proved, once and for all, that the cast piston has an advantage in fuel burning engines and Hagon is now ready for an attempt to become the first man to get into the “nines” in Great Britain.

Hagon was one of the pioneers of special sprint frame in Britain and nearly all machines now have the extra-long chassis. But whether these are really necessary is still a matter for discussion. When the American teams came over to Britain, local riders scoffed at their frames, expecting the near-standard items to be unrideable on the home strips. Of course, they weren’t, and the British belief that there is no substitute for wheelbase took a knock.

George Brown still believes that a motorcycle should look like a motorcycle, whether it’s designed for drag racing or any other purpose, and his big Vincents are sufficiently roadworthy to compete in paved hilí climbs. But there’s no doubt that a lengthened wheelbase and a shallow fork angle do aid high-speed steering and takeoff. The short American frames are no argument. Most U.S. motorcycles would go quicker and have less navigation problems if the engines were in lower, longer frames.

A large percentage of the machines at the two British meetings were fitted with superchargers which, in the big classes at least, are practically a necessity for good times. Adding a blower to a machine can increase its weight by as much as 20 percent. Add to this the power lost driving the blower and it’s obvious that there must be a pretty fair advantage to be gained with the unit.

Once set up correctly, a supercharger is a fairly foolproof item and now at least a couple of riders are experimenting with blowers on quarter-liter single-cylinder machines.

The National Sprint Association Meeting was a field day for Wal Phillips, maker of the Phillips Fuel Injector. This instrument, although not a true injector as the fuel is mixed with the air before it reaches the inlet tract and not squirted directly into the combustion chamber, certainly works well and was used by seven record breakers. Tuning for flat-out throttle openings is easy with the instrument. If any criticism is to be levelled at the Phillips Injector it is that the fuel mixture varies as the head of fuel in the tank drops. On a road machine this slight drop in richness is unimportant and with machine running on fuel, excessive richness at the outset will make hardly any difference to the performance.

It’s taking a long time for British sprinters to break the 10-second barrier but, despite the scarcity of nitro fuels and the fact that events are all held on old runways having far from ideal surfaces, they are determined to catch up with their American cousins. ■