STATE OF THE SPORT

Mark Rechtin

IN LATE 1959, A GROUP OF NERVOUS executives from Johnson Motors, Inc. gathered around a conference table with Hirobumi Nakamura, then director of sales for the newly created American Honda Motor Corporation.

The Johnson group had heard rumblings about this new Japanese importer, and of its wild claims of expected sales in an American motor-

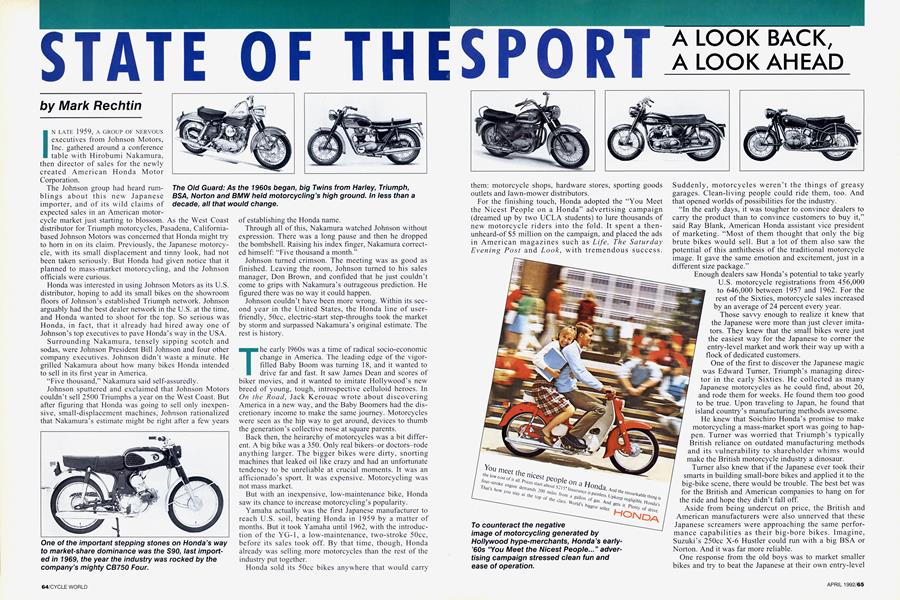

cycle market just starting to blossom. As the West Coast distributor for Triumph motorcycles, Pasadena, Californiabased Johnson Motors was concerned that Honda might try to horn in on its claim. Previously, the Japanese motorcycle, with its small displacement and tinny look, had not been taken seriously. But Honda had given notice that it planned to mass-market motorcycling, and the Johnson officials were curious.

Honda was interested in using Johnson Motors as its U.S. distributor, hoping to add its small bikes on the showroom floors of Johnson’s established Triumph network. Johnson arguably had the best dealer network in the U.S. at the time, and Honda wanted to shoot for the top. So serious was Honda, in fact, that it already had hired away one of Johnson’s top executives to pave Honda’s way in the USA.

Surrounding Nakamura, tensely sipping scotch and sodas, were Johnson President Bill Johnson and four other company executives. Johnson didn’t waste a minute. He grilled Nakamura about how many bikes Honda intended to sell in its first year in America.

“Five thousand,” Nakamura said self-assuredly.

Johnson sputtered and exclaimed that Johnson Motors couldn’t sell 2500 Triumphs a year on the West Coast. But after figuring that Honda was going to sell only inexpensive, small-displacement machines, Johnson rationalized that Nakamura’s estimate might be right after a few years of establishing the Honda name.

Through all of this, Nakamura watched Johnson without expression. There was a long pause and then he dropped the bombshell. Raising his index finger, Nakamura corrected himself: “Five thousand a month.”

Johnson turned crimson. The meeting was as good as finished. Leaving the room, Johnson turned to his sales manager, Don Brown, and confided that he just couldn’t come to grips with Nakamura’s outrageous prediction. He figured there was no way it could happen.

Johnson couldn’t have been more wrong. Within its second year in the United States, the Honda line of userfriendly, 50cc, electric-start step-throughs took the market by storm and surpassed Nakamura’s original estimate. The rest is history.

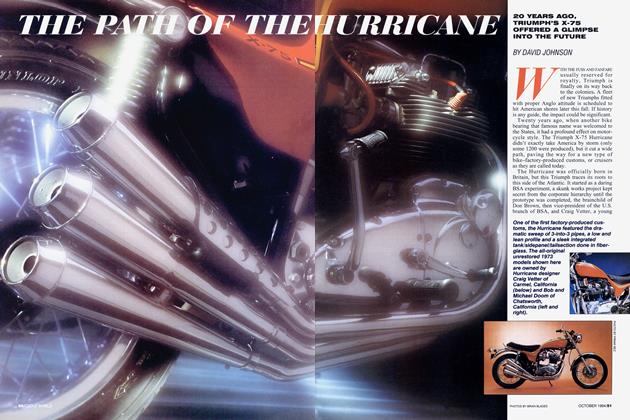

The change early in 1960s America. was a The time leading of radical edge socio-economic of the vigorfilled Baby Boom was turning 18, and it wanted to drive far and fast. It saw James Dean and scores of biker movies, and it wanted to imitate Hollywood’s new breed of young, tough, introspective celluloid heroes. In On the Road, Jack Kerouac wrote about discovering America in a new way, and the Baby Boomers had the discretionary income to make the same journey. Motorcycles were seen as the hip way to get around, devices to thumb the generation’s collective nose at square parents.

Back then, the heirarchy of motorcycles was a bit different. A big bike was a 350. Only real bikers-or doctors-rode anything larger. The bigger bikes were dirty, snorting machines that leaked oil like crazy and had an unfortunate tendency to be unreliable at crucial moments. It was an afficionado’s sport. It was expensive. Motorcycling was not mass market.

But with an inexpensive, low-maintenance bike, Honda saw its chance to increase motorcycling’s popularity.

Yamaha actually was the first Japanese manufacturer to reach U.S. soil, beating Honda in 1959 by a matter of months. But it took Yamaha until 1962, with the introduction of the YG-1, a low-maintenance, two-stroke 50cc, before its sales took off. By that time, though, Honda already was selling more motorcycles than the rest of the industry put together.

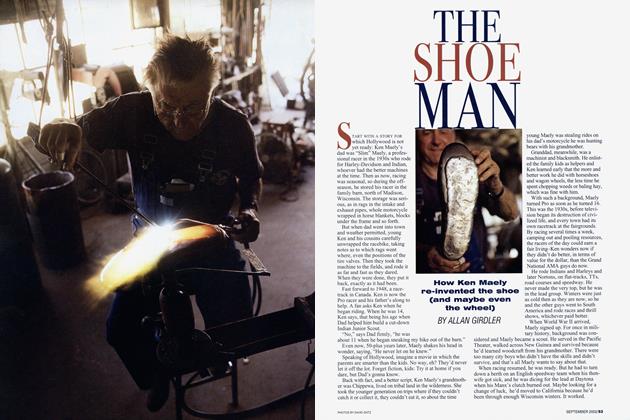

Honda sold its 50cc bikes anywhere that would carry them: motorcycle shops, hardware stores, sporting goods outlets and lawn-mower distributors.

A LOOK BACK, A LOOK AHEAD

For the finishing touch, Honda adopted the “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda” advertising campaign (dreamed up by two UCLA students) to lure thousands of new motorcycle riders into the fold. It spent a thenunheard-of $5 million on the campaign, and placed the ads in American magazines such as Life, The Saturday Evening Post and Look, with tremendous success.

Suddenly, motorcycles weren’t the things of greasy garages. Clean-living people could ride them, too. And that opened worlds of possibilities for the industry.

“In the early days, it was tougher to convince dealers to carry the product than to convince customers to buy it,” said Ray Blank, American Honda assistant vice president of marketing. “Most of them thought that only the big brute bikes would sell. But a lot of them also saw the potential of this anthithesis of the traditional motorcycle image. It gave the same emotion and excitement, just in a different size package.”

Enough dealers saw Honda’s potential to take yearly U.S. motorcycle registrations from 456,000 to 646,000 between 1957 and 1962. For the rest of the Sixties, motorcycle sales increased by an average of 24 percent every year.

Those savvy enough to realize it knew that the Japanese were more than just clever imitators. They knew that the small bikes were just the easiest way for the Japanese to corner the entry-level market and work their way up with a flock of dedicated customers.

One of the first to discover the Japanese magic was Edward Turner, Triumph’s managing director in the early Sixties. He collected as many Japanese motorcycles as he could find, about 20, and rode them for weeks. He found them too good to be true. Upon traveling to Japan, he found that island country’s manufacturing methods awesome.

He knew that Soichiro Honda’s promise to make motorcycling a mass-market sport was going to happen. Turner was worried that Triumph’s typically British reliance on outdated manufacturing methods and its vulnerability to shareholder whims would make the British motorcycle industry a dinosaur.

Turner also knew that if the Japanese ever took their smarts in building small-bore bikes and applied it to the big-bike scene, there would be trouble. The best bet was for the British and American companies to hang on for the ride and hope they didn’t fall off.

Aside from being undercut on price, the British and American manufacturers were also unnerved that these Japanese screamers were approaching the same performance capabilities as their big-bore bikes. Imagine, Suzuki’s 250cc X-6 Hustler could run with a big BSA or Norton. And it was far more reliable.

One response from the old boys was to market smaller bikes and try to beat the Japanese at their own entry-level game. Harley, which had led in nationwide marketshare prior to the Honda invasion, sold Italianbuilt lightweights. It didn’t work.

Honda 1969 by shocked unveiling the the motorcycle CB750 Four, world the in first big Japanese bike to be sold in the U.S. Whereas most American or British bikes cost upwards of $2000, the CB750 was introduced at just $1295. And it was faster than almost anything on two wheels.

That was the last thing the big-bike makers wanted to see. In response, Harley-Davidson scrapped its small-bike production and sold out to American Machine & Foundry (AMF) to get enough cash to compete with Honda on the highend. Veterans Norton, BSA and Triumph, already on the road to extinction, now had to compete on Honda’s terms. Although they created some incredible bikes-the BSA/Triumph Triple’s speed records stood for several years in the early ’70s-the Japanese had the old boys whipped on price. Within five years, just Harley and Triumph remained. Barely.

Commensurate with its manufacturing growth under AMF, Harley had serious quality-control problems. These included oil leaks, questionable electronics and reduced durability. While it got cash from AMF, Harley lost loyal customers who thought the sale had sullied the way the company made motorcycles.

Shortly after Honda’s CB750 introduction, Kawasaki followed suit with its Z-l. The devoted following that the Japanese manufacturers had garnered at the entry level moved up to the big bikes, creating another incredible boom in motorcycle sales. From just over one million bikes sold in 1970, more than 1.5 million bikes were sold in 1973, the all-time high for the motorcycle industry. Kawasaki’s market share zoomed from nine percent in ’72 to more than 17 percent in the Z-l’s first three years.

At the same time, Yamaha also had been gaining on Honda’s market, with Suzuki and Kawasaki nipping at its heels. At the beginning of the ’80s, Yamaha made a crucial decision: catch Honda. Honda already had the most models of motorcycles, and had the showrooms and customer base to support them. Yamaha didn’t, and neither did Suzuki and Kawasaki, but all three joined in the race anyway.

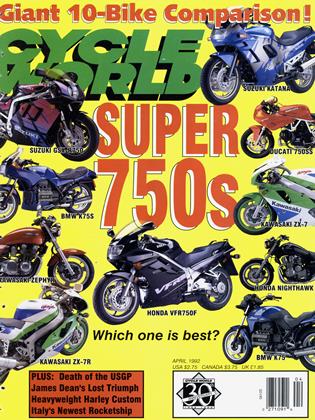

New technologies came out every year through the 1980s. Kawasaki hit paydirt with the GPz, then with the Ninja follow-up that Tom Cruise immortalized in Top Gun. Suzuki had the GS series, and then the GSX-Rs and Katanas. Yamaha introduced the Secas, the FJ series and the FZRs. And Honda had the CX Turbo, the Interceptor and, finally, the CBR. The industry was selling one million bikes a year, and Honda was still selling almost half of them. Between Honda and Yamaha, more than 100 models were pushed on the market in 1984 in a crazed quest for technological one-upmanship and greater marketshare.

For a few years, the buying public bit. Sales soared again from just under one million in 1982 to more than 1.3 million in 1984. But a combination of rapid depreciation of the bikes, shrinking demographics, soaring insurance costs and a recession in the United States took bike sales into a nosedive that didn’t stop until 1990-when only 462,000 bikes were sold.

All these screaming-fast sportbikes crowded the showroom floors, leaving little room for cruisers or entry-level bikes. Dealers, facing a choice of too many model lines, often didn’t carry entire series of bikes. Since superbikes carried the biggest profits, most dealers stuck with them. Those who overbooked often were stuck with four or five years of inventory on their floors.

Motorcycles that went for $4599 one year dropped to $2499 the next. Buyers looking to trade in their used bikes for new found their mounts were nearly worthless, even after only three years on the road. Getting a good trade-in deal for a Japanese bike was nearly impossible.

“We were playing a chicken game, so when demand fell, the big guys were stuck with all this inventory,” said Mark Blackwell, American

Suzuki’s marketing director. “It should have been a buyer’s market, but even the consumers were cautious. There were so many bikes that they were getting dirty sitting on the showroom floor. No one wanted to buy in a fire-sale atmosphere. The bikes were like leftovers.”

Also, by concentrating on big bikes, the Japanese were ignoring the introductory-level motorcyclist.

“Although the superbike would make more profits, it would eventually decrease the number of people from the buying public walking into the stores. They were intimidated by the superbikes,” said Don Brown, who went from Johnson Motors to executive positions at Suzuki and Triumph/BSA before doing independent consulting.

In retrospect, “the machines needed to be radical in their styling and technology in order to justify the price and stand out among the clutter of non-current bikes. In 1982, it seemed like the right thing to do,” said John Gale, Yamaha product manager.

The market for streetbikes got so bad that in 1984, more dirtbikes and ATVs were sold than streetbikes.

With such miserable prospects, Harley-Davidson took two drastic steps to fight for its survival. The Japanese had continued to produce cruisers that imitated HarleyDavidson’s all-American look, and Harley was hurting financially-this only a few years after buying itself back from AMF.

First, Harley promised any buyer of a Sportster that if he traded it back within two years for a Big Twin, he’d get the original purchase price of the bike back for the down payment. In an era when Japanese bikes depreciated by 50 percent just sitting on the showroom floor, HarleyDavidson suddenly found itself popular with customers who wanted a motorcycle as an investment.

The marketplace was in a downward spiral, and nothing seemed to work.

“Whenever you bought a Japanese bike, it was always too soon,” said Jerry Wilke, Harley vice president of sales and marketing. “At the same time, we gave a guarantee. It was security for the buyer. The bike was an asset, not an expense.”

Secondly, Harley officials made an appeal to the

Federal Trade Comission, claiming the Japanese were dumping their cruisers in America at less than fair market value. They won the case, and an incremental tariff structure was set up on foreign-made over-700cc bikes to protect Harley-Davidson’s price competitiveness.

Harley also was the first dealership chain to encourage lengthy test rides, which lured back many customers who wanted to see if Harley workmanship had improved after the firm bought itself back from AMF.

The results were immediate. Harley’s market share jumped from five percent in 1986 to 17 percent in 1990, passing Kawasaki and Suzuki.

Nonetheless, the marketplace was in a downward spiral, and for the rest of the players, nothing seemed to work. What’s more, the Baby Boomers were getting married and becoming Yuppies, and motorcycles weren’t part of the picture. Since the Japanese had ignored the entry-level customer, they suddenly found themselves with a stagnant customer base that had shrunk significantly.

One example of scaring off the entry-level market was an advertising campaign initiated during one early-’80s Super Bowl that showed a collection of knee-dragging sportbike riders barreling through corners. To the three million riders watching, the commercial looked like great fun. To the 27 million other viewers that the ad sought to reach, the commercial merely confirmed their suspicions that motorcycle riders were crazy, their bikes intimidating.

Incidentally, Yamaha took the brunt of the 1980s warring with Honda. While industry sales dropped, Yamaha’s marketshare did too, though never out of second place. Only recently has it recovered. “Yamaha isn’t as strong as it used to be,” Gale said. “We took too much of a risk during the ’80s. We thought we could be Number One. We got caught.”

As nation the sport of a moves recession into the and 1990’s, high motorcycle the combiprices means more buyers are hanging onto their bikes longer. “The manufacturers kept the average price up at $7000, and that went beyond the reach of a lot of riders. It’s not a disgrace any more to have a five-year-old motorcycle, but that’s not good for the manufacturers,” said Don Emde, winner of the Daytona 200 in 1972 and a former publisher of Dealernews.

Other industry insiders agree. Since most consumers can’t get a decent trade-in on a bike they bought during the glutted ’80s, most have decided to run the bikes “into the ground,” said Bob Moffit, Kawasaki vice president of marketing.

So where does the industry go from here? All the manufacturers believe that the sharp drop in sales has bottomed out, even though the current recession has hindered any chance of immediate turnaround. A good sign that the bike market may rebound is the increase in dual-purpose sales among the children of the Baby Boomers, almost a cyclic parallel of how the sport boomed 30 years ago, according to Yamaha’s Gale. And though getting into the sport has become more and more expensive, the used-bike market has flourished-indicating that the overall motorcycle market is in better health than new-bike sales would indicate.

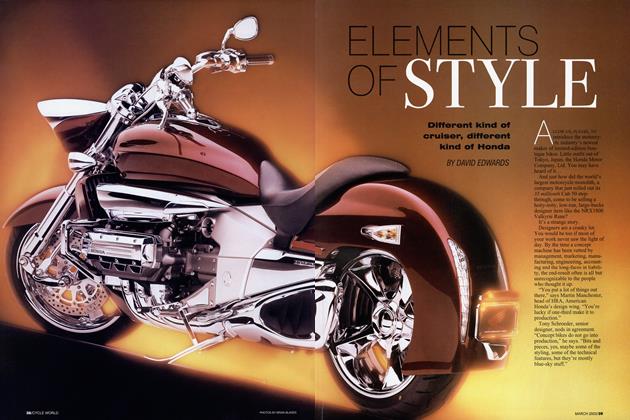

The recent American craze with retro-fashion and the sudden avoidance of conspicuous consumption have led the bike makers to return to building standards, big cruisers and, to a lesser extent, price-conscious entry-level bikes.

“We’re trying to address the retro style, but fashions and design have changed,” said Kawasaki’s Moffit. “Motorcycles don’t look the same now. While they can look retro, they can’t look old. They have to have the modern design elements and styling trend, but with the fundamental, masculine motorcycle elements. A retro bike can’t look cute.”

Honda marketer Ray Blank said that his company will place more emphasis on off-road bikes to attract the entry-level customer again. “That’s where you can take younger riders and teach, supervise and coach them-let them develop the love for the sport. There’s no traffic lights and no Freightliners. Once they’ve learned that way, the kids can’t wait until they’re 16,” Blank says.

Harley-Davidson’s Wilke thinks it will take more than a good old-fashioned bike or a small dirtbike to attract new buyers.

“You need to give the customer reasons to ride. Only then will he come back to buy another one,” Wilke said. “The industry has forgotten that people don’t buy a motorcycle just to go to work or the store. They can do that in a car, too. If you can’t give them a reason to ride a motorcycle, the customers are going to lose interest.”

Taking a jab at the Japanese manufacturers, Wilke said the Japanese dealer mentality is, “If you never see the customer again, that just means there isn’t a problem with the bike. With Harley-Davidson, the sale is just the beginning of a long-term relationship.”

The Japanese manufacturers, of course, can retort that they started the Discover Today’s Motorcycling program in such an effort. Rider education, helmet-use campaigns, government lobbying and image marketing to the non-riding public didn’t get much support before the industry banded together. It took the staggering new bike sales decline to unite the industry to figure out what would be best for the manufacturers, the dealers and the customers.

It will take more than a good old-fashioned bike or a small dirtbike to attract new buyers.

Consultant Brown said that the chance for another sales boom is slim, but an increase in sales is possible, given that the average age of motorcycles on the road is at an all-time high. Those bikes will have to be scrapped soon, and a savvy marketing campaign could very well lure owners back into the showroom for another ride. Brown challenges the manufacturers to achieve that goal.

“There’s too much hairsplitting over one mile-anour in these bikes today, and the technology makes

AY prices ridiculous. But there’s also no real imaginan in building standard bikes, so they get tagged as 0 leap’,” Brown said. “A long time ago, 100 miles an ,uur was awful fast. Has that really changed? It makes you wonder just where we’ve gone.”

Mark Rechtin is a business reporter for the Pasadena, California, Star-News.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontUncle George's Last Ride

April 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Enchanted Vagabond

April 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCRocket Fuel

April 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1992 -

Roundup

RoundupNow On Sale: $75,000 Gp Racebike

April 1992 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

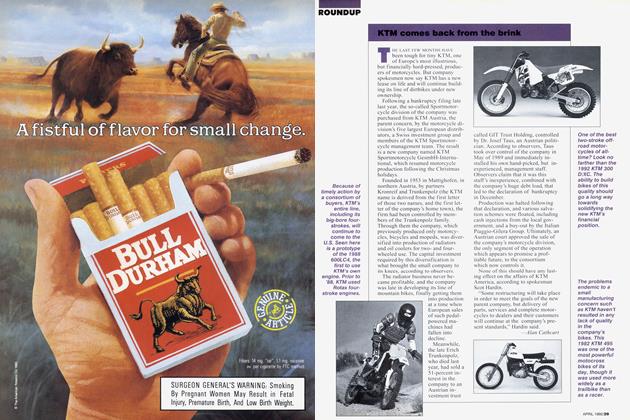

RoundupKtm Comes Back From the Brink

April 1992 By Alan Cathcart