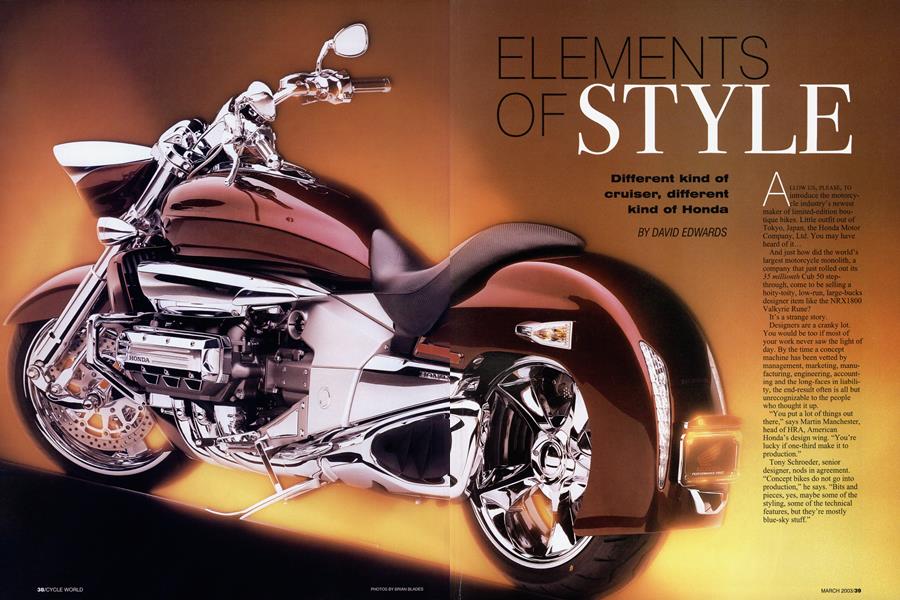

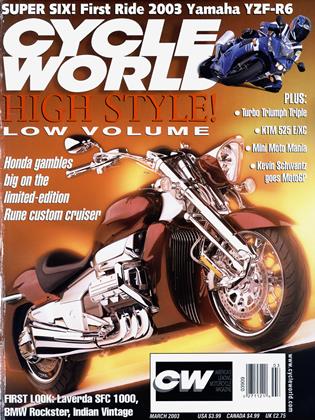

ELEMENTS OF STYLE

Different kind of cruiser, different kind of Honda

DAVID EDWARDS

ALLOW US, PLEASES TO introduce the motorcycle industry's newest maker of limited-edition boutique bikes. Little outfit out of Tokyo, Japan, the Honda Motor Company, Ltd. You may have heard of it...

And just how did the world’s largest motorcycle monolith, a company that just rolled out its

35 millionth Cub 50 step-through, come to be selling a hoity-toity, low-run, large-bucks designer item like the NRX1800 Valkyrie Rune?

It’s a strange story.

Designers are a cranky lot.

You would be too if most of your work never saw the light of day. By the time a concept machine has been vetted by management, marketing, manufacturing, engineering, accounting and the long-faces in liability, the end-result often is all but unrecognizable to the people who thought it up.

“You put a lot of things out there,” says Martin Manchester, head of HRA, American Honda’s design wing. “You’re lucky if one-third make it to production.”

Tony Schroeder, senior designer, nods in agreement. “Concept bikes do not go into production,” he says. “Bits and pieces, yes, maybe some of the styling, some of the technical features, but they’re mostly blue-sky stuff.”

With the Rune, however, blue sky has reached the assembly line. In largely unadulterated form, this is a concept bike you’ll be able to buy when it hits Honda showrooms this spring as an early-release 2004 model.

“A designer’s dream,” states Manchester. “I can’t believe we actually did it.”

“The number-crunchers didn’t get in the way,” explains Schroeder. “We didn’t have to sacrifice, to water down, any of the design elements.”

Signature item among those design elements is the massive trailing-link fork assembly, an outgrowth of another Honda concept cruiser, the Zodia showbike of 1995. In R&D ever since, the fork as fitted to the Rune runs about 4 inches of wheel travel. Those meaty front tubes are merely sliders. Tie-rods translate suspension action from the lower link to an upper rocker arm attached to twin enclosed shocks-one for springing, one for damping-mounted behind the chromepeaked headlight. Anti-dive properties could have been part of the package, but the fork is configured to react conventionally under braking. Speaking of which, the front 330mm rotors are the largest ever fitted to a Honda streetbike.

Turns out its front end leads the Rune in more ways than one. American Honda officials first saw the productionized trailing-link setup attached to an early prototype of the VTX 1800 power-cruiser.

“It was so cool,” says Ray Blank, VP of motorcycles, and the man who is principal in green-lighting any new U.S. project for production. “We loved the look, but it cost too much for the VTX, which had to come in under $15,000.” About this same time, Honda was in a quandary about its Valkyrie cruiser. Internally, the bike was a favorite because of its trademark 1520cc flat-Six motor, borrowed from the previous-generation touring Gold Wing. But the model seemingly had reached its sales saturation point. The Interstate version, with fairing and hard luggage, would soon be dropped. Ditto the Tourer bagger. Things did not look particularly good for the remaining base version, either.

“The Valkyrie never became mainstream,” says Blank. “But it had a strong following. As soon as the rumor hit that the bike was in trouble, we started getting tons of email-Please, do not let the Valkyrie die!”

He remembered that proto VTX with the link fork.

“Could it work on a new Valkyrie 1800?” asked Blank. “Can we do something really special?”

Of course, said the designers at HRA, already at work on various concepts and sketches for a second-act Valky.

Enter the T1, T2 and T3 design mockups, rolled out for public consumption at the Long Beach motorcycle show in December of 2000, all sprayed a bright lemon yellow so that paint schemes weren’t an influence on opinions about the bikes. Clipboards in hand, researchers mingled among the crowd, taking notes. Live-wire cruiser-types were invited to participate in later focus-group sessions.

These took place in the HRA compound, a lock-down facility on the American Honda campus in Torrance, California. Confidentiality agreements signed, participants were ushered into a room where moderators led the free-wheeling, sometimes argumentative discussions. Behind mirrored glass, a video camera and more note-takers. “It can get emotional,” says Manchester. “You want to know what they like and how much-you’re measuring the ‘love’.”

What soon became clear was that one of the bikes, T2, was generating more love than the others. This was pleasing to Manchester and Schroeder. While Tl and T3 had been overseen by HRA, the actual building was farmed out. T2 had been conceived, clay-modeled and constructed in-house. It had an aluminum frame, single-sided shaft-drive swingarm (running a Unit Pro-Link shock, just like Rossi’s RC21IV!) and the new GL1800 engine, hot-rodded to produce more than 100 rear-wheel horsepower and 100-plus foot-pounds of torque. T2 also had Blank’s leading-link fork.

Asked to explain the bike’s appeal, Schroeder credits what he calls its “Neo-Retro” feel, as in new technology, new design but with style overtones that borrow paradoxically from the streamlined art-deco movement and American hot-rod cars of the 1950s. The latter is evident in the chromed valve covers jutting out for all to see; in the multi-bar radiator grille, looking very ’32 Ford; in the overdone, almost cartoonish Lakes-style exhaust pipes; in the Halibrand-lookalike wheels, the rear complete with a faux knockoff spinner-though Honda’s liability nannies, apparently quaking at the thought of Ben Hur-inspired lawsuits, axed the spinner for production.

“It’s like a slammed ’51 Mercury,” enthuses Schroeder. “Very American.”

“Of course, the T2 was our favorite, the one we wanted to win, the way we wanted to go,” admits Manchester, but it was the focus groups’ strong reactions that led to some wild thinking at HRA and eventually to the Rune being built with the concept design almost intact.

“They were very emotional, very passionate about the bike,” recalls Schroeder. “And they were adamant: We want all of this.”

Blank picked up on the enthusiasm for keeping the Rune whole, and liked the idea, but could it be done? Would the big bosses in Japan sign off on something this grandiose? Honda is, after all, an engineering company, a racing company, but here was a twowheeled peacock of the highest magnitude, uncomfortably ostentatious. The old proverb about the nail that sticks out getting pounded down still holds meaning in Japan. Plus, it would have to be expensive, maybe as much as $30,000.

“It was a tough sell,” Blank says. “It went all the way to the top. This is not the kind of thing Honda does. There’s an element of bravado here that’s hard for the Japanese to get their minds around. Honda is a cost-conscious, consumer-driven company. The Rune is an extravagant motorcycle.”

Afterhours lobbying ensued, much time sitting shoeless under low tables. “Long dinners is where this stuff gets done,” says Blank wryly.

In the end it was his argument that the Rune would be “the most special production custom any company has ever built” that won the day.

“Everybody knows we can do it with sportbikes,” he argued, noting the NR750 oval-piston and the RC45. “But we need to express how much passion we have for this kind of motorcycle. We should do this because we can, not in a bragging kind of way, but just to show what Honda is capable of.”

He was so persuasive, in fact, that Japan set up a special committee just for the Rune, where hours were spent discussing different types of metal finish, the deepness of chrome, how various lines and radii interacted with each other. All very Zen. “It was draw and erase, draw and erase, draw and erase...,” relates Blank.

Nobody at Honda is talking price or production numbers. Between $20,000 and $30,000 was as close as we could determine, and one Rune per dealership would put the U.S. allotment at 1200 bikes, but a big, fat “No comment” was all we got in response to that suggestion.

“We won’t make many-we don’t want to, and besides, we can’t,” says Blank. “We have no mass-production capabilities for this bike.”

“Our goal is to make a few people very happy,” says Schroeder.

“Not everyone will understand this bike, but the ones who do, the ones who buy it, will be out in the garage every day waxing the thing,” adds Manchester.

A local, long-time dealer thinks demand will far outstrip supply, telling us, “At first, I thought, no way, this is too weird, too much money. But I’ve sold three sight-unseen, with no guarantee that I’ll get that many and no idea what the final price will be. I’m now in the position of turning down $500 deposits.”

What a concept...

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontResurrection, Inc.

March 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsFamous Harley Myths

March 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBurning Race

March 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

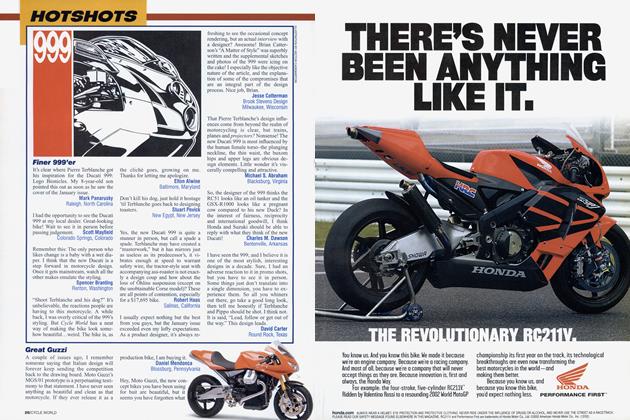

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

March 2003 -

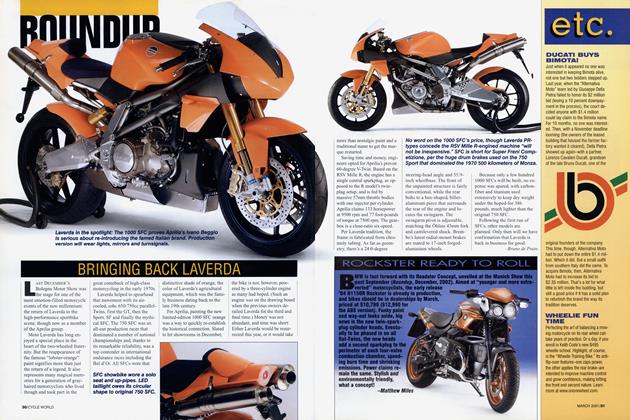

Roundup

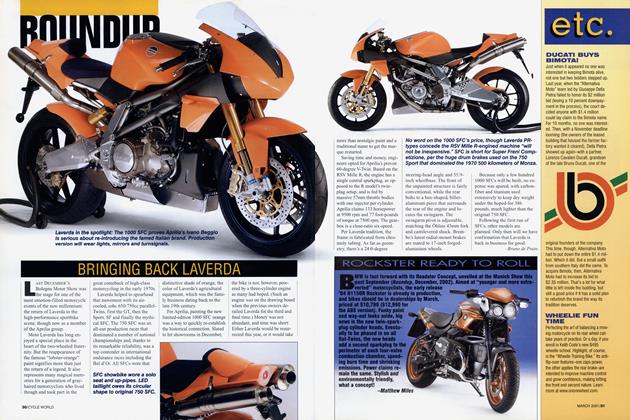

RoundupBringing Back Laverda

March 2003 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupRockster Ready To Roll

March 2003 By Matthew Miles