THE PATH OF THE HURRICANE

20 YEARS AGO, TRIUMPH’S X-75 OFFERED A GLIMPSE INTO THE FUTURE

DAVID JOHNSON

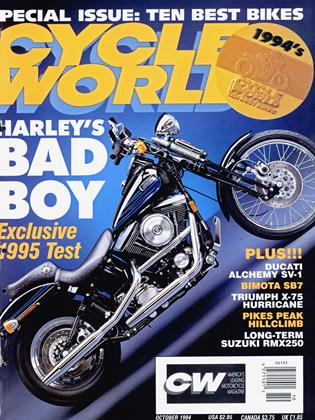

WITH THE FUSS AND FANFARE usually reserved for royalty, Triumph is finally on its way back to the colonies. A fleet of new Triumphs fitted with proper Anglo attitude is scheduled to hit American shores later this fall. If history is any guide, the impact could be significant.

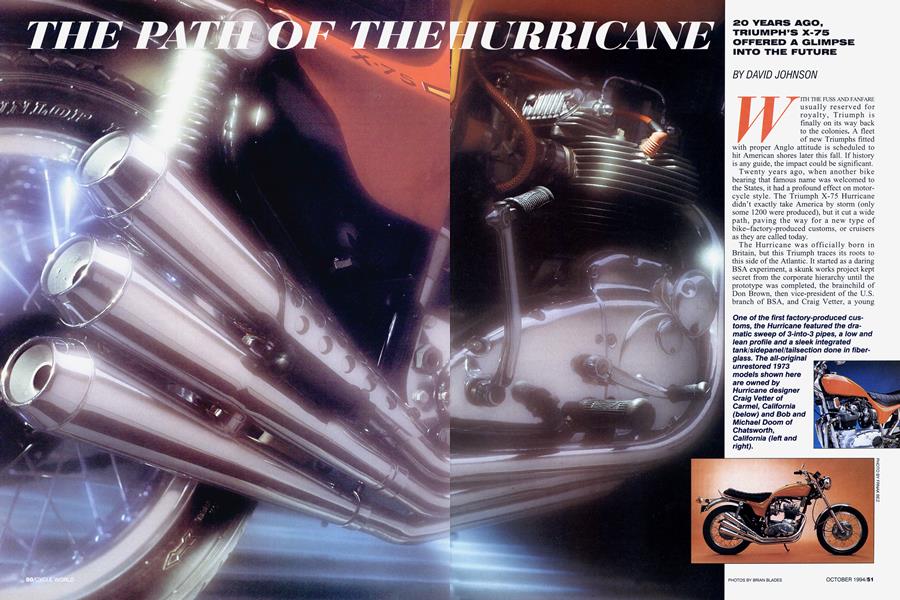

Twenty years ago, when another bike bearing that famous name was welcomed to the States, it had a profound effect on motorcycle style. The Triumph X-75 Hurricane didn’t exactly take America by storm (only some 1200 were produced), but it cut a wide path, paving the way for a new type of bike-factory-produced customs, or cruisers as they are called today.

The Hurricane was officially born in Britain, but this Triumph traces its roots to this side of the Atlantic. It started as a daring BSA experiment, a skunk works project kept secret from the corporate hierarchy until the prototype was completed, the brainchild of Don Brown, then vice-president of the U.S. branch of BSA, and Craig Vetter, a young motorcycle enthusiast recently graduated from the industrial design program at Champaign, Illinois.

Both men were open to a new style that might shake up the industry. In the mid1960s Brown had predicted that the Japanese motorcycle companies would pose a serious threat, and was not at all convinced that the soon-tobe-unveiled BSA Rocket Three was an adequate weapon to fight them. Vetter, who was just establishing the fairing business that would eventually make his reputation and his fortune, was anxious to show off his design abilities and was searching for a manufacturer that would let him restyle a motorcycle.

Both had clear visions of what they hoped to see. Brown’s was fueled by a memory of his very first bike, a customized Triumph Thunderbird he had bought in the 1950s-what one might describe as a British bobjob or a streetbike in the flattracker style. Vetter’s image was more futuristic: a sportstyled fiberglass seat-tank unit for the Triple.

Brown and Vetter may not have been kindred souls or have shared the same purpose in creating the Hurricane, but eventually they found a common goal in restyling the Rocket Three. The result was that Vetter got a Triple from BSA’s headquarters in New Jersey and set to work in June of 1969.

He started the styling process the way a hot-rodder would-by stripping the bike, a decision that had an important influence on the final product. Off went the tank, seat and sidecovers. In his journals, Vetter wrote, “I am terribly impressed at how good the BSA looks with the gas tank off. The massive engine is now obvious. I must design the tank to allow visual clearance to see the cylinder head.”

A chromed headlight assembly supported by a tubular brace replaced the bulky, black-painted stock unit. Boranni aluminum rims were substituted for the stock steel rims. A Ceriani fork was too short, and was extended. Smaller polished stainless-steel fenders took the place of painted steel units. The front fender was attached to the fork with classic Triumph-style braces. The rear fender and a taillight were mounted close to the seat’s grabrail.

By September of 1969, Vetter was ready to put the finishing touch on the Hurricane: its pipes. After sketching numerous alternatives, he settled on a dramatic effect-three headpipes flowing into three gently upswept reverse-cone megaphones. Once it was coated with a flare of Camaro Hugger Red paint (which is actually orange) and gold Scotchlite tape with black pinstriping, the Hurricane prototype was complete.

But before it could go to the consumers, the bike had to get past the top brass at BSA/Triumph, where financial trouble had brought about a changing of the guard-an influx of people who were savvy businessmen, but not motorcyclists-among them Peter Thornton, the man in charge of BSA in the U.S.

It didn’t take an enthusiast, however, to know that this motorcycle was hot. When Vetter brought the Hurricane to New Jersey in late 1969, Thornton’s response was more than enthusiastic. “My God, it’s a bloody phallus. That’s the most exciting thing I have ever seen,” he exclaimed. “Send it to England.” The bike was on its way that afternoon.

But it languished in a warehouse for many months and wasn’t introduced to the scrutiny of motorcyclists until Vetter restored the Hurricane prototype and Cycle World presented it to readers in September of 1970 with the question, “Is this the next BSA Three?”

Today, we know that the Hurricane, though marketed as a Triumph, was actually the last BSA Three (the two companies merged while the bike was being designed), but at the time the answer was much less clear. As Tony Salisbury, BSA’s director of marketing and product planning, told the magazine, “People have seen bikes like this before-customs. But never from the manufacturer. We want to know if consumers agree with the design.”

There was no question the design was different. Vetter felt that successful design could often be found in counter-cultural movements. He knew right where to look for inspiration: the chopper craze.

“Chopper people recognize, unconsciously, perhaps, the animalness of a motorcycle, its feeling of power,” said Vetter. “Look at a lion. Deep chest, paws forward, the rear end light. There’s something primitive in us that we associate with that and transfer into motorcycles. The BSA is an assimilation of some of these ideas, some of the stimuli around me-it is what’s happening today.”

Forward thinking, to say the least. Vetter’s genius was in seeing that the American cultural phenomenon of choppers could have any role in the design of factory-produced motorycles-given that the chopper was supposed to be a mechanical statement of individuality. “You can buy your identity,” he insisted, “if you buy the right motorcycle.”

In 1970, Cycle World made clear that this motorcycle might be the right one for many. And not just for its style, but its substance too. “It seems not only to make the machine more modem, but more livable. Seating is quite comfortable, and it is obvious that Vetter has paid attention to rider position,” staffers wrote. “He has definitely succeeded in coming up with a bike that invites you to climb on and take it for a ride.”

The response from readers was just as positive. The magazine was inundated with letters, and normal supplies of additional copies were exhausted at once.

If BSA had been looking for a sign that the Hurricane might make it in the marketplace, this was it. The bike went into production and appeared on the pages of Cycle three years later.

When staffers there rode an early production model, however, they weren’t very impressed. The bike-by this time marketed as a Triumph Hurricane, when BSA merged with the company-struck some as “two-wheeled buffoonery and the product of epic bad taste.”

Cycle seemed to think that Vetter misread the American market with his factory-produced custom, sacrificing function for form: “Customizers look on production motorcycles as blank sheets of canvas; and straightforward enthusiasts don’t particularly care how their bikes are styled, as long as they’re good enough and as long as the styling doesn’t interfere with the functionality of the bike in question.”

Of course, history has vindicated Vetter’s insight that individuality was a commodity that could be purchased in the form of a motorcycle. Today, cruiser sales are stronger than ever, and the riders of Yamaha Viragos, Honda Shadows, Suzuki Intruders, Kawasaki Vulcans and Harley Softails seem to feel that their purchase has endowed them with instant individuality-despite the fact that thousands of other people are riding virtually identical bikes.

But even though Cycle may have missed the mark when it questioned the wisdom of factory-produced customs, it was right on target when it measured the functionality of the Hurricane and found it lacking because “several of the bike’s tricky styling touches-however pleasing to the eye-keep the bike from being as good, and as reasonable, as it was when it was nothing more than a good ol’ Rocket Three.”

First on Cycle’s list of function complaints was the front fork which, because of longer tubes and revised triple clamps, had more trail than the stock fork. The visual lightness created by this change resulted in heavier low-speed handling and flexing of the fork under heavy braking. The bodywork came under criticism primarily because the 2.6gallon steel fuel tank lurking beneath the sleek fiberglass effectively limited riding range to about 75 miles.

Also of concern: the exotic three-pipe exhaust system, which put a serious dent in cornering clearance. BSA representatives suggested that the bike wasn’t meant to be a corner carver. “If not that,” Cycle responded, “then what?” With its 1.5-person saddle and small fuel tank, the Hurricane wasn’t a reasonable choice for touring duty. All that was left was to go “cruising down the street trailing a vicious snarl and attracting attention.”

Exactly. The Hurricane was among the first of a new class of motorcycles-what we now call cruisers.

Prominent places on the continuum of motorcycle history are most often granted to bikes that represent technological advances-motorcycles are, after all, machines. But the Hurricane has earned its place by willfully, and beautifully, ignoring the notion that form follows function. In the wake of the Hurricane, style became a type of substance.

No, there wasn’t a big move to one-piece fiberglass bodywork for streetbikes. But the notion of blending together the lines of what had traditionally been separate pieces-gas tank, sidecovers and seating area-for a flowing one-piece look caught on in the late 1970s and early 1980s (just look at the lines of the Honda Nighthawks) and is still very much with us.

And you need only look at the multitude of cruisers crowding America’s showrooms and roads to know that the British-made/American-designed Hurricane blasted through the States with a strong gust that the industry is still feeling today. Œ

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Last Indian

October 1994 By David Edwards -

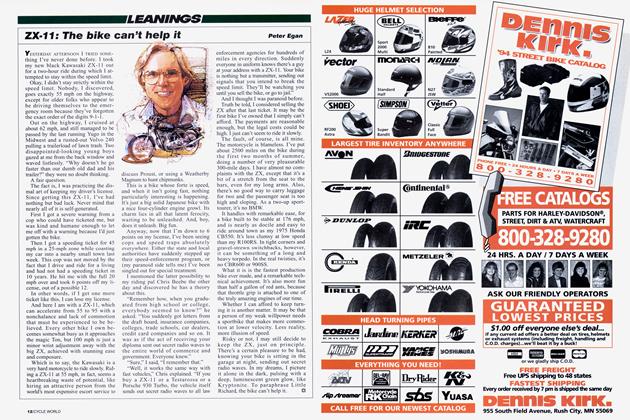

Leanings

LeaningsZx-11: the Bike Can't Help It

October 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCGrace In Hardware

October 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1994 -

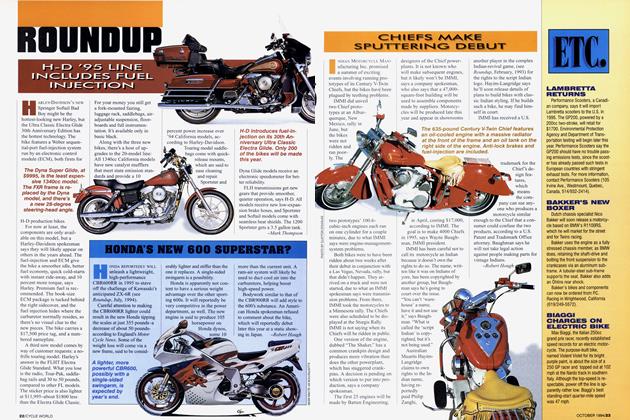

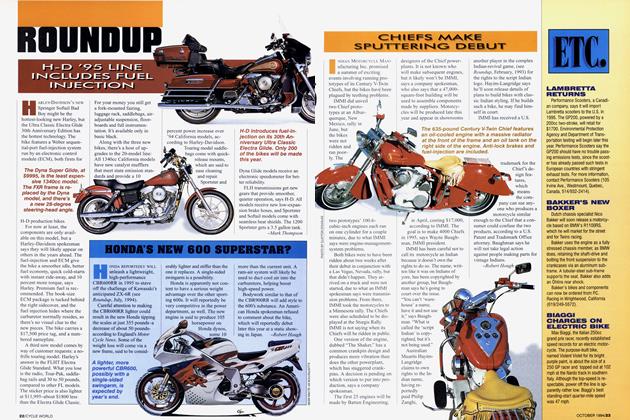

Roundup

RoundupH-D `95 Line Includes Fuel Injection

October 1994 By Mark Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's New 600 Superstar?

October 1994 By Robert Hough